Sybil’s Plan To Ruin Liz!—Elizabeth Taylor & Richard Burton

London correspondent has said that Sybil Burton laughed a hearty Welsh laugh when the battery of high-toned and oh-so-precise English lawyers explained the “master plan” to her: Richard, her husband, would give her $1,000,000. Elizabeth Taylor would give her an additional $500,000. She (Sybil) would leave England immediately—scat! like a cat! on the run! fast! out! She would then, in proper time, have the courtesy to give Richard a divorce so Liz could marry him! If Sybil laughed, however, when she first heard all this—if she said, “Bloody nonsense! Good Lord, what’s to be the next step in this comedy we’ve all been playing? Am I now to be paid off and take my two daughters and be pushed into exile?”—the laughter, the semi-amused wonderings, did not last for long. Because, the following day, Richard himself reportedly had a talk with her. Over tea. In the living room of the lovely little house in suburban-London which they had bought soon after their marriage fourteen years ago, where they had known happier hours than this. Where now Richard told his wife that Liz had said something to him which should not be considered lightly—considering the source. That Liz had said, very simply, “Marry me, Richard, or I’ll die.”

Six words of stark passion, of vague threat, from the lips of a temperamental and sometimes hyper-emotional woman; words which—once repeated now—transferred the living room of the lovely little house in suburban-London into a gray and tomb-like and silent place. As the Burtons sat looking at one another, the tea in the cups they held became colder . . . colder—though not nearly so cold as the chill that suddenly took hold of Sybil Burton’s heart. She had feared this all along—this threat of threats from Liz. She remembered now Rome, ’62, a similar threat, how Richard had ignored it then—how Liz had suddenly been rushed to the hospital—how Liz’ press agent had talked the next day about “bad chili” while someone else had talked about “bad oysters”—while the majority of Rome newspapers had hinted strongly at sleeping pills and stomach pumps.

Sybil remembered. And she knew now that this was the moment when—for her conscience’ sake, as well as for Richard’s—she would have to give in to the “master plan,” to leave her husband. Just as she realized that, by so deciding, she had somehow come up with a plan of her own—a plan to ruin the woman who had caused her so much heartbreak and humiliation. A simple plan, really. A foolproof and ironic plan. One which would require only time. And which, when the time came, would hit—with sledgehammer force—the very same Liz Taylor who recently had told a reporter, sweetly: “It’s very hard to admit you’ve done wrong. If mistakes hurt other people, in the long run you will have to pay for them. . . .” That’s what she’d said.

It had not been in Sybil Burton’s nature to plan things—vengeful or otherwise—before Rome, and “Cleopatra” and the Liz-Richard mess began. She’d been, up to that time, a free spirit who’d taken life as it had come; who’d enjoyed its ups, shrugged off its downs and who’d always, as the Welsh say, “looked forward to a prettier morning.”

Certainly, for the first twelve-or-so years of their marriage, no woman could have been more tolerant of her husband’s wanderings—his affairs with other women. Certainly, no woman could have put up so easily with this fine young actor who also happened to be the possessor of an unkempt’ soul. And a devil of a temper; this faithless and often-exasperating and demanding and hard-drinking bloke whom many a friend of Sybil’s—and even of Richard’s — maintained she could well do without. But Sybil, it so happened, loved the bloke, loved him desperately. And for an even occasional return of this love, she would do anything for him. Anything. Like forgive him. And console him. And mother him.

This was her greatest mistake, some say. To Sybil, Richard was a little boy at heart—gay and fun-loving and candid and basically good, so good. She knew that Richard’s own mother had died when he was barely two years old. She felt that often he needed, even at this later age, a woman who would make up for his loss, who would baby him from time to time. So she became that woman. Like many a mother, she became very permissive with him. Her unique attitude towards his countless affairs are a case in point here.

Like many a mother, she became very defensive about him. (“Richard is an artist,” she would say, “—he can’t be held back. It would be cruel to try to tame him completely, to chain his spirit! He has places to go, don’t you see? And he will only get to those places by being himself!”)

She became, after a while, like the mother who—as Richard’s career began to zoom—was so proud her baby was now taking good and solid first steps that she didn’t see the possibility of his legs becoming so strong and free that, in time, he would use them to run away from her—for good.

To a real mother, this is a sad but natural moment, a fact of life, of nature’s way.

But to a wife who has been playing mother—it is the tragic moment.

As it happened with Richard when he began to work on “Cleopatra” with an actress named Elizabeth Taylor. . . .

Sybil’s viewpoint

If $40,000,000 have been spent on “Cleopatra,” the film—40,000.000 words, at least, have been written about the Burton-Taylor affair, which began shortly after the film got underway.

Sybil, in the few interviews she has given to columnists and reporters, has maintained that she barely read a word of all this—at first.

And this, strangely enough, is true.

Liz, to Sybil, was not the most beautiful woman in the world, the most all-consuming man-eater of our time, the femme fatale extraordinary, the girl who had everything—and who always wanted more. But rather, to Sybil, Liz was an actress with whom her husband happened to be working, and spending the greater part of his day. She was the leading lady with whom temporarily, like others before her, he would fall in love . . . and then, fall out of love, as soon as the play-acting was over. It was only a familiar pattern.

Besides—and let’s face it—Sybil was wise enough to the ways of publicity and star-making methods to realize that Richard could only benefit financially from all this. After all, if certain other “actors”—with pretty faces and no talent—could command enormous sums for picture-making. just because they were images and publicity-happy sorts, why shouldn’t her husband—with his not-exactly pretty face but with his fantastic talent—reap the same financial benefits now that it was all at his fingertips? Thanks—yes, thanks—to Elizabeth Taylor.

But when, suddenly, the publicity grew out of hand—and Sybil would open her morning edition of Il Messageroand see those pictures of Liz and Richard smooching, off the set; when she began to hear from close friends that Richard and Liz had taken an apartment in mid-Rome, that December of 1961, where they would meet after the director had called his final “cut!” for the day; when Eddie Fisher, poor Eddie, flew to New York one day, suddenly, and announced—after a short and mysterious stay in a private hospital— that he was through with Liz, that she had put him through hell . . . then, and only then, did Sybil begin to feel that this was different now. That things had changed suddenly. That the pattern, so steadfast in the past, had gone askew now. That she had met her match in Liz Taylor. That her husband was on his way to leaving her for another woman.

For a while, she said nothing to Richard about this. “It will end, it must end,” she thought. “Prettier mornings—they are not far away.”

But as time passed—and production ended on “Cleopatra”—and when Richard, who had told a reporter, “Immediately after this film I will make another, on the Riviera probably, and the entire production will amount to approximately what Miss Taylor earns in a week!”—when Richard suddenly seemed to forget about the Riviera and his low-budget picture but flew off to London—with “Miss Taylor,” to begin work with her, again, in something to be called “V.I.P.s” . . . Sybil Williams Burton knew, in her heart of hearts, that from now on those prettier mornings would be harder and harder to come by.

The low time

“The most difficult time for me,” she told a Photoplay source recently, “was the now-I-have-him, now-I-don’t period”—referring, obviously, to the four weeks she spent in London last spring, when Richard “dated” both her and Liz, and when a favorite parlor sport among the Mayfair set was to keep count on how many hours Richard spent with whom.

In fact, the jokes about the three be- came rampant—not to mention vulgar. Among the biggest joke-makers, surprisingly were former “dear” friends of Sybil’s and Richard’s, who now found the situation just too-too amusing and far-out for words.

Sybil, however, couldn’t have cared less about all this.

Her only concern now was Richard—and whether or not she could bring him to his senses and back to her and their two little daughters.

Says our source, “She would speak to him of the family he was preparing to toss aside. Never just of herself. Never—‘please, at least for the sake of the children.’ But always Sybil would use the word that to the Welsh, perhaps more than to most other peoples, is so important and emotion-wracked: family. ‘We are a family, Richard,’ she would say, ‘and that is the way we must remain!’

“But,” our source goes on, “it was no use. While Sybil was pleading, Liz was in her suite at the Dorchester—alone—and fuming. And when Burton would return to her, she’d say things. And it was when she said those fateful words—‘Marry me, or I’ll die!’—that it became clear which of the two women would be victorious in laying claim to Richard Burton!”

Victory, however, can be a very sometimes thing.

As we know, Sybil finally acquiesced to Liz’ demands. One night, without fanfare, she signed the separation papers drawn up by the London lawyers; the following morning she and her two daughters boarded a jet for New York, as good an “exile” site as any other.

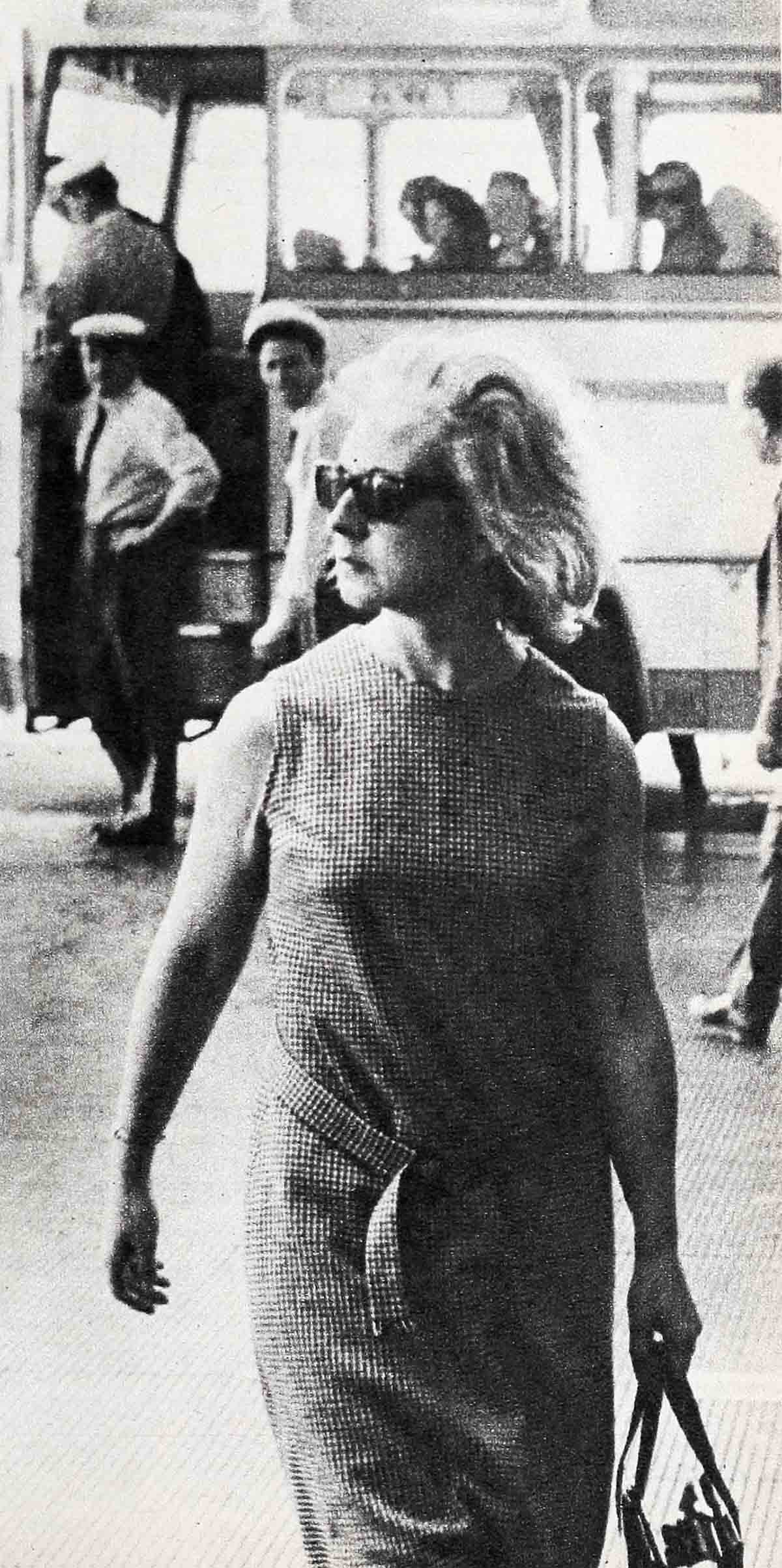

On her arrival in New York, interestingly, one reporter noted that “Sybil wore a chic suit and a wan smile, and she carried a large and handsome alligator purse.”

What he didn’t note, however, was that she also carried a plan with her, tucked somewhere behind the wan smile—a plan, without malice, without legal complications, but with giant-sized scoops of irony. A plan that would eventually ruin the woman who had set out to ruin her.

Step one

Like all good plans, Sybil’s is a simple one.

For a while—for as long as she can—she will hold back from giving Richard his divorce. After all, that $1,500,000 (and she could have held out for $5,000,000 if she’d wanted to) did achieve a legal separation—a removal of the wife from the scene—but nothing could force Sybil to divorce her husband.

Meanwhile, Liz and Richard would be kept guessing, feeding on hope without hope. And meanwhile, hopefully, Richard might well begin to grow tired of Liz. And come back home where he belonged.

This part of the plan is based on Sybil’s deep-felt belief that, “I’ll have Richard back some day.”

She knows, for one thing, that Liz and Richard have begun to fight constantly—in their suites at the Dorchester, in restaurants, in theater lobbies, practically everywhere.

She knows, for another thing, that Richard feels guilty about the whole situation—witness his recent quote to a magazine reporter: “You may be as vicious about me as you like. You will only do me justice.”

She knows, too, about Liz’ possessiveness—how, as one writer put it, “she demands twenty-five hours a day of Burton’s time!”—and she, Sybil, just happens to be an expert on how her husband feels about freedom.

She feels more than anything that an innate streak of decency in Richard will bring him back to her and his daughters.

Sybil’s quiet vengeance here?

Liz will then emerge the laughing stock of our time. The love goddess who couldn’t get her man. The glamor-puss with egg all over that puss. The empress without a consort. The loser—this gal who has never lost anything in her entire life—except, maybe, a diamond bracelet or two.

However, should this part of the plan fail to work out—should Richard himself decide to sue for divorce, or should additional threats force him to do so—then Sybil shifts easily into part two of her plan.

A marriage betwen Liz and Richard, she knows, is bound to end up, let’s say, less than perfect.

First of all, it’s as obvious to Sybil as it is to millions of others that the juice of this current “grand passion” between Liz and Burton is based on the element of scandal—the giddiness that comes from shocking the multitudes—the joy that comes from being clandestine—the shivers of delight that come from being so marvelously and brazenly unorthodox.

But turn this all into that most orthodox of situations—marriage; legalize this union, sanction it, take away the kicks—and then what have you got?

A very nervous and depressed Liz and Richard.

“—A Liz,” as someone who has known her since her first marriage has told us, “who will wonder why her husband’s eye is beginning to rove, why he isn’t around her as much as he used to be—who will begin to get so annoyed with Husband No. Five that it won’t take her long to begin looking around for the next prospect.”

“—A Burton,” as someone who knows him well says, “who will not quite understand why Liz is beginning to object to his little flings, why—instead of understanding him, his nature, his needs—she’s tossing those vases all over the place . . . why, instead of mothering him, she’s tossing off phrases that would have any other mother blushing.”

In other words, it’s clear that after five or six months of such a marriage—all hell will break loose. That Richard will remember with fondness and longing the halcyon days when he had everything a man could want.

And the day he decides he’s had enough of Liz—there will be Sybil, waiting to pick up where they left off. . . .

In her innocent, uncalculated plan to ruin Liz, this is the step of steps:

To give Liz—for a while—the burden of being Mrs. Richard Burton!

— MICHAEL JOYA

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1963

No Comments