James Stewart – On The Q.T.

One of the peculiarities of Hollywood casting is that players called on to portray famous contemporary figures frequently bear no resemblance whatever—either external or in temperament—to their subjects. This, however, is quite definitely not the case with the man who will bring to the screen what is perhaps the most enviable role of the decade—that of General Charles Lindbergh.

Lindbergh reportedly is a methodical man. So, in spades, is forty-six-year-old James Stewart, who maintains filing systems for everything short of his socks.

Lindbergh, despite the awesome depth of his fame, seldom makes news of the sort that sends managing editors scurrying for the scare-head type. Neither does Stewart, whose most spectacular utterance during a recent session with the press was the disclosure that his thirty-five-year-old house was beset by termites.

Lindbergh can take public contact or leave it alone, and leans somewhat to the latter. So does Stewart. But there is no confusion in the mind of either man on the point that public contact is part of their business.

And it is here that a dissimilarity sets in. In this respect, Stewart is by far the more mellow and graceful of the two. There is reason to believe that he does not care especially for the incidental trappings of stardom. But he faces them in the dogged, head-scratching manner of a true son of Indiana, Pennsylvania—and with the assurance of Princeton, class of ’32.

Not many people know James Stewart well. Only a handful, for example, would be aware that he has no special fondness for his more popular handle, Jimmy, and is called simply Jim by his intimates. Though millions feel on rather cozy terms with him, the logical offshoot of his exceptionally warm and direct personality, no more than a few would know that he never appears in waking hours without his shoes highly polished. And while everybody, so to speak, has knowledge of his splendid war record, a very small percentage of everybody would have the information that this is not to be discussed in his presence. He never, literally never, mentions it, not even to his wife, who was Gloria Hatrick McLean.

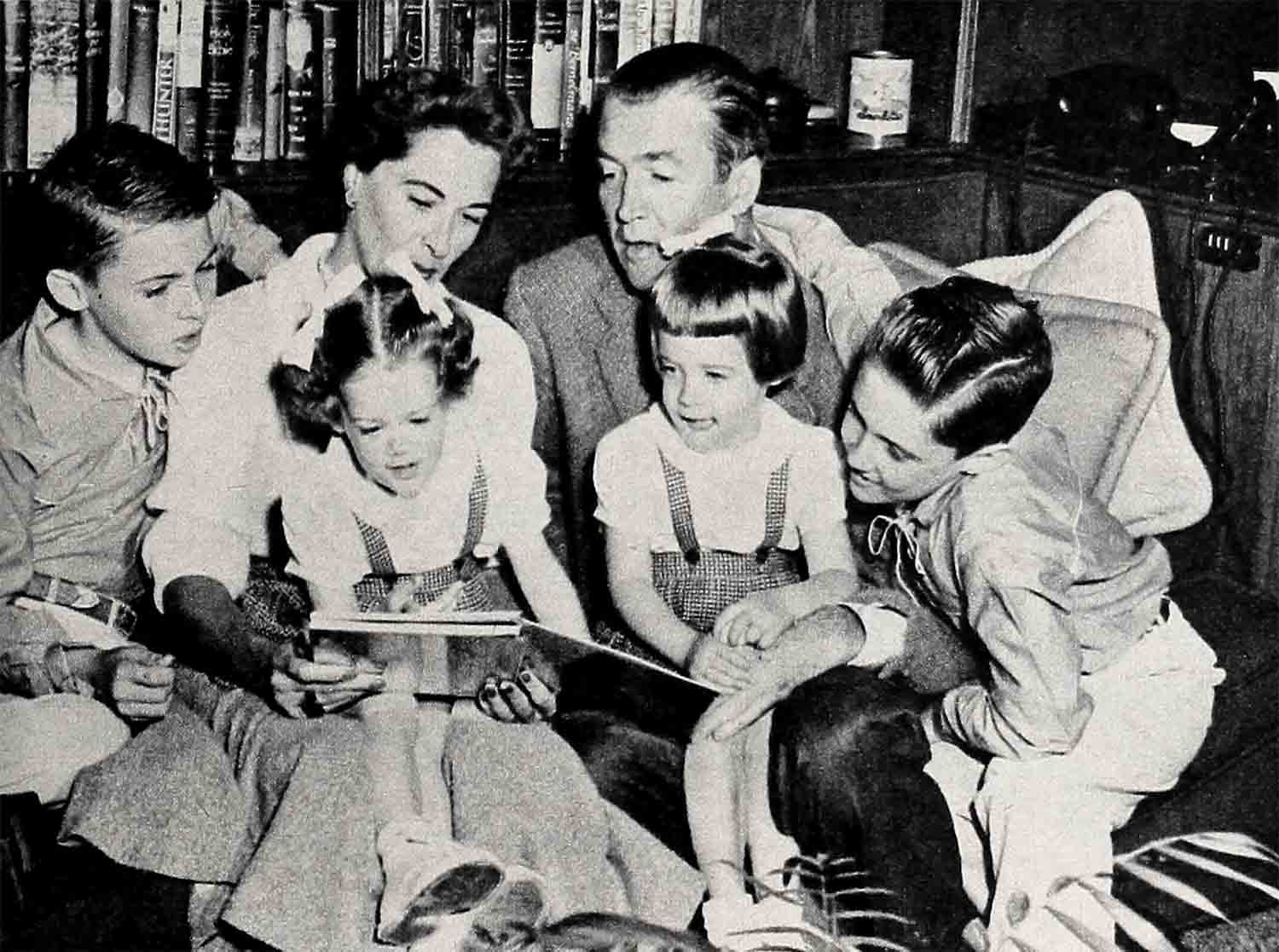

Gloria Hatrick McLean met James Stewart at a dinner party at the home of Rocky and Gary Cooper early in October 1948. It is Mrs. Stewart’s recollection that they did not address one another at all, but did a great deal of looking. Some time after that, on the heels of a devoted courtship, Stewart invited her over to his house one night for dinner. She was pleased to accept. In the middle of the entree, Stewart—who had not exactly been babbling up to then—put down his fork and said: “Will you marry me?” Again, she was pleased to accept. “Yes,” was the sum total of her answer.

“That,” a friend remarked to her later, “was a fast way of doing it.”

“Why not?” said Gloria. “I wasn’t stuck for an answer.”

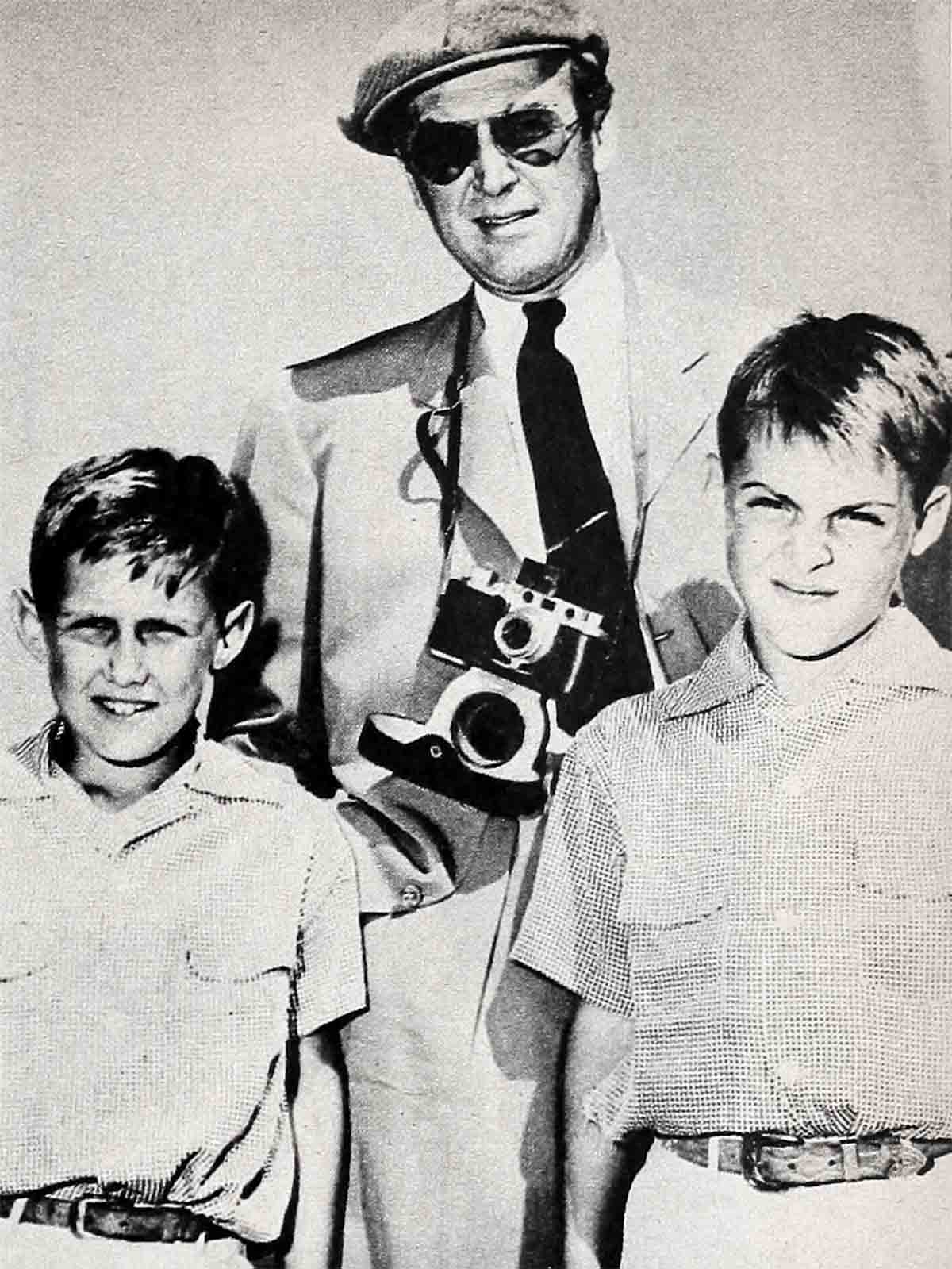

Mrs. Stewart had two sons by a prior marriage: Ronald, who is eleven now, and Michael, nine. She and Stewart are the parents of twin girls, Judy and Kelly, four. The combined circumstances led to a contretemps during the purchase of the Beverly Hills home they now occupy. The front was thickly covered with ivy, a facade which Mrs. Stewart did not like.

“It’ll have to go,” she said. “The place looks like a dormitory.”

“Well,” said Stewart, aptly enough. “What else is it?”

The front is still covered with ivy.

Methodical is perhaps too mild a term for James Stewart. More properly, he is meticulous. A handy man around the house—especially in matters having to do with carpentry—he maintains his tools with such fanatic precision that he could go to the smallest screw driver in the dark. He is an ardent amateur photographer and has his vast equipment assembled in the same fashion. In details of dress it is as true. Stewart’s wardrobe is not extensive. “Why buy a suit?” he once protested to his wife. “I’ve got a suit!” His formality in clothes is not pervasive—slacks and a cashmere jacket are uniform around the house. His Ivy League tastes insist on ties, and for going-out purposes, dark blue suits. The day he went to war, he hung his best dark blue suit precisely in moth balls. The day, several years later, he came back, he did the same with his Air Force uniform, replete with the eagle of full colonel, and went right to where the suit was. It fitted him fine.

Stewart’s friends declaim as one that he is a droll fellow in a solemn, unobtrusive way, and there are narratives to support the view. One has to do with a Glendale preview of an early Stewart film, where a small boy approached him for an autograph.

“Didn’t I give you one last week?” asked Stewart, whose memory for faces is remarkable.

“Yes, sir,” said the boy, who was a nice little boy but blindly dedicated to a mission. “But I’ve gotta have five of yours to swap for somebody good.”

The speech still moves Stewart to mirth. But he was nothing if not cooperative. Patiently he signed five pages of the boy’s album and handed it back to him. “Might as well get this done in one operation,” he observed. “Somebody good’s liable to turn up any time.”

For Stewart, that was quite a speech. While not a strong, silent man on the order of his friend Cooper, he is more of a conversational counter-puncher than a lead-off man, and he rarely says anything without thinking about it first.

“Jim’s the kind of a guy,” an intimate has reflected, “that if you say to him, ‘How are you?’ he’ll tell you. He’s got no idle patter at all.”

Cooper has even less. It was thus that there occurred one afternoon the incident of the long, long drive. Stewart was enjoying an unaccustomed day off. Had it all to himself. But he wasn’t enjoying it. Idleness has an abrasive effect on his nerves.

“These wonderful days off,” he has said, “you look forward to so much, have a way of being a frost. You call friends. They’re not home or they’re busy doing something else. You run out of things to do. So there you are. Nowhere.”

Well, this crisis had arrived when Cooper came by.

“Go for a drive?” he called.

“Might’s well,” said Stewart.

They drove for three hours. Not a word was exchanged. At the end of the afternoon, Cooper dropped Stewart off again.

“So long,” he said.

“See you around,” said Stewart.

He re-entered his home.

“How is Coop?” said Mrs. Stewart.

“Dunno,” said Stewart. “Didn’t ask him.”

The Stewart household runs on a schedule about as exacting as that of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Rail Road. Breakfast is served at a certain time, lunch at another, dinner at another. The time is always the same. There are no deviations. If the Stewarts lunch out, they do so at Romanoff’s. No place else. Every Thursday evening, while in residence, they dine at Chasen’s. Same table; same time. They do not go to night clubs unless the entertainer is one they particularly like. Each July 4th, they assemble the children and go to the fireworks at Los Angeles’ Coliseum. Not to perform this ritual would be unthinkable. Most evenings they spend either at home or at the home of one of a limited circle of close friends. The preferred diversions here are records, talk and canasta, a game for which Gloria Stewart has displayed near genius.

Left to their own devices, on the other hand, the Stewarts like to tackle somewhat knottier problems. Stewart has a chess-player’s mind. So has his wife. The two also subscribe to a jig-saw puzzle library—it seems there is such a thing—which monthly services them with a staggering jigsaw. This is not kid stuff but a mosaic rigged to cover a small acre of floor. Mrs. Stewart generally does the heavy duty on these while Jim kibitzes.

The two are in truth very fine parents. It’s a situation that cannot be overstated.

Jimmy is kind but firm. “Discipline,” he has said with a striking wisdom, “provides them with a sense of security. Undisciplined youngsters become insecure because there’s no pattern they can trust.” Bad report cards mean loss of downstairs privileges for the boys, and they jolly well know that Pop means it. Asked once if he gave them allowances, Stewart said he didn’t, rather on the grounds that they were too young to be on salary.

The Stewarts are tireless picnickers—Stewart was never happier than when, on one birthday, he was given a fancy fitted picnic basket. They are enthusiastic golfers and really zealous fishermen, a pursuit at which Stewart’s enjoyment is only slightly marred by the circumstance that Gloria always hauls in a bigger fish.

Stewart has a small number of crotchets, one of which is being interviewed without prior briefing. His thought processes are more thorough than they are fast, and he feels rather off balance when speared with no warning. At Omaha for the world premiere of Paramount’s “Strategic Air Command”—Warner’s will produce Lindbergh—he was notified only ten minutes in advance that he was to emcee the stage proceedings, presenting such mighty brass as General Curt LeMay. He wasn’t at all happy about it.

“You fellas,” he once remarked querulously to a reporter, “ought to give a guy a little warning. Come up and ask me all of a sudden what I did yesterday, I wouldn’t be able to tell you. Mind freezes up.”

But on termites, he discourses fluently.

“It’s a scientific fact,” he announced a while back, “that when wood gets to be as old as the wood in my house, it’s delicious. To termites. They not only eat three times a day but begin to snack between meals. I’m expecting them to add pepper and salt any time now.”

He shows faint irritation when asked if he plans to retire. One day last spring his nasal voice sharpened notably when he addressed the subject, and the famous drawl became nearly staccato.

“No, I’m not going to retire!” he said. “Why should I? This is my profession. This is what I do. I love it. You pick your career and then there’s no such thing as enough. Not yet anyway. Lord, I can’t even take a year off. The competition’s gettin’ too tough. Too many good young actors coming up behind you.”

Stewart’s consideration for other persons is—if the word is not a prissy one—almost exquisite. He would not, for example, think of imposing on his servants’ time off, and recently, when he hosted one of his rare cocktail parties for a visiting Eastern dignitary, he had Chasen’s cater it rather than ask his own staff to work overtime.

And finally, Stewart’s a rabid movie fan. In his converted cellar, he has a 16-mm projector, a screen and a few easy chairs, and runs whatever films he can get his hands on. Or if he hasn’t got his hands on any, the Stewarts just plain go to the movies. On occasion, he runs his own pictures for the family.

James Maitland Stewart was born in Indiana, Pennsylvania on May 20, 1908.

Jim went to Mercersburg and then Princeton, had some idea he’d like to be an architect, majored and graduated in it, in fact, but then turned to acting. This was not haphazard. He was a pretty hot shot in Princeton’s polished Triangle Club, and it was more than evident that he had talent.

He worked on the New York stage for a while but came to Hollywood pretty fast by conventional standards. He got off in pictures practically on top and has not stepped down since. Nor is he especially likely to.

Stewart’s enlistment as a private in the Army Air Force was one of the rare times on which he was able to gain weight. Rejected the first time for a deficiency in this respect, he acquired seven pounds as fast as he could and wasn’t turned down again.

He was a model private—a trifle more than a model private, according to one man who served with him, due to an anxiety to adjust to the unit and cancel out his identity as a film star. His rise to colonel thereafter was richly deserved and had no connection whatever with his being a screen celebrity. Obviously, in fact, the Army does not fool in these matters.

Stewart’s record in bombers flying from England in World War II is rote. He flew twenty-five missions over enemy territory.

Then the war was behind him. He’d done what he had to do, it was over, it was time to get back to work. That was all.

If there was a problem of readjustment, he has never mentioned it. Of course, the blue suit was waiting. No moth holes. No problem there. And the career was waiting, right where he’d left it. No problem there. And Gloria McLean was waiting—somewhere—although neither knew it at the time.

It has been said of Stewart, who did not marry until he was 41, that on an earlier date he came within a whisker of wedding a top female star. This is true except for one thing. It was a very formidable whisker. The whisker was that, as in the case of Gary Cooper’s health, he didn’t ask her.

That is the story of the man who plays Lindbergh.

THE END

—BY JOHN MAYNARD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1955

No Comments