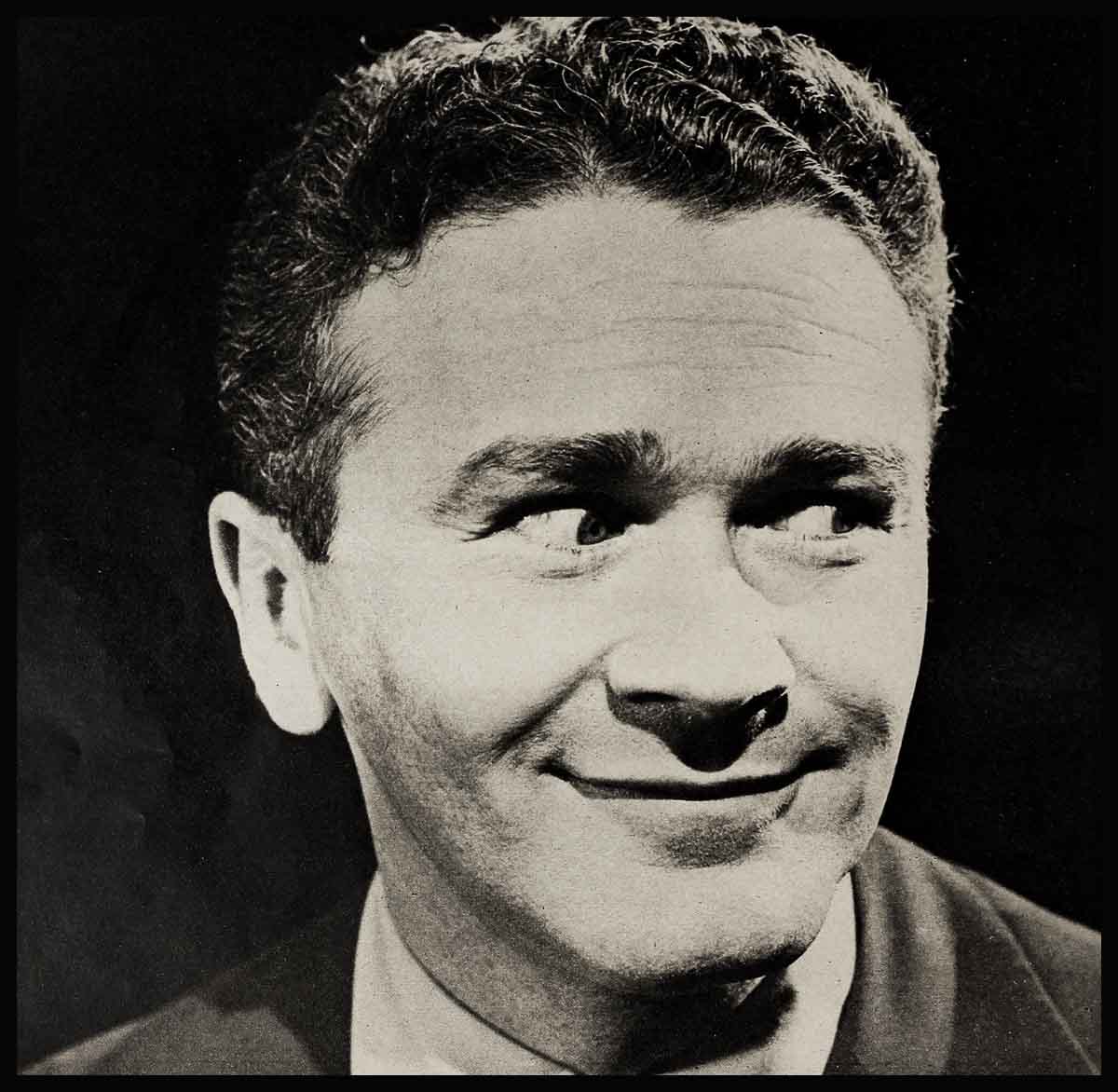

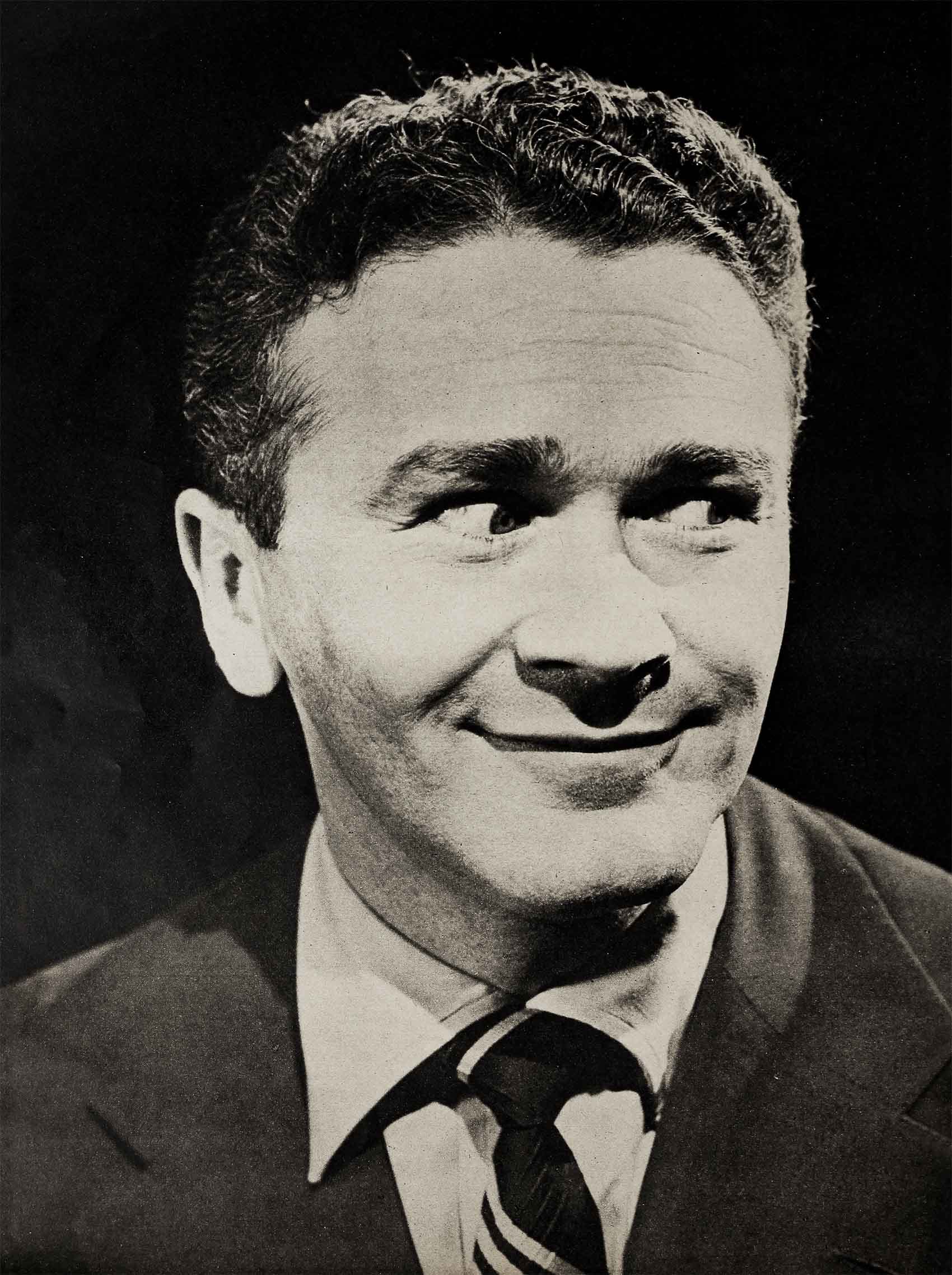

“You I Like!”—Red Buttons

The little guy was scared, but you could never tell it by looking. He laughed and clowned on the stage during rehearsal and he behaved as though he had always belonged there.

He was a brand new TV star, “the brightest comedy discovery of the year,” or so all the critics had said the week before when he made his television debut.

“Then what do I have to worry about, now?” he tried to reassure himself. “I’m in.”

But Red Buttons knew better. At 33, he was a show business veteran. It wasn’t opening night the stars and headliners really worried about. It was the second night. If the critics and audience panned a show when it opened, it didn’t matter much what happened the next night, but if they liked you, if they stood up and cheered, “This boy’s got it! He’s a hit!” then the second night jitters set in.

You’ve got to follow yourself. You’ve got to be as good, if not better, than you were the night before so the. fans will continue to say, “He’s a hit!” instead of, “What do they see in him? He’s a flash in the pan. He can’t sustain the pace.”

That was what worried Red Buttons even though the first and second nights for his TV show were a week apart. He had never been in this predicament before. When he was a kid in the Catskills trying out his jokes on an audience of summer vacationers, he was too young and inexperienced to be scared. When he was in burlesque or the nightclubs or theater, the second night jitters weren’t so bad. His act was the same. He didn’t have to worry about new material. All he had to worry about was himself.

Television was different. You couldn’t do the same thing every time. Each week had to be an entirely new show. “So what if they liked me last week,” the boyish-faced comic with flecks of grey in his curly brown hair, nagged himself. Show business was a funny thing, he knew. A star today and a bum tomorrow. He had worked too hard, too long to lose it now.

He thought of his mother and father at home in the Bronx, waiting to see him live up to his notices. He thought of his wife, Helayne, who loved him so and helped to ease the hurt of an unhappy first marriage.

The nervous tension of the years of work and waiting welled within him and as he thought of the night ahead and all his yesterdays, Red Buttons collapsed on the TV stage.

He didn’t go on that second week in October last year. A film was hastily shown instead and the css switchboards were flooded with calls from friendly fans concerned about the comic they had taken to their hearts but a few days before.

That reassurance of their faith in him, the loyalty they showed, their willingness to laugh and sympathize gave him the will and strength he needed to make secure the stardom televiewers had bestowed upon him.

The following week and every week thereafter, Red Buttons continued to endear himself to his fans. If they believed in him, he could believe in himself.

Funny, he secretly admitted later, that he who had never dared lose confidence in himself lest he lose all his hopes should have lost it at the moment when his dreams were fulfilled. He was a star, nationally known and nationally applauded.

Ever since he could remember, he had wanted to be a star.

To anyone but him it might have seemed an impossible dream. Aaron Chwatt, the second of Michael and Sophie Chwatt’s three children, was born in a fourth floor walk-up in a tenement in New York’s lower East Side on February 5, 1919.

His parents were poor but happy. His father earned $18 a week blocking hats in a millinery shop. He had a quiet dignity and an old world philosophy that children are the future of a country. Michael Chwatt wanted his children, Joe, Aaron and Ida, to be a credit to their parents and to their country.

Sophie Chwatt was born in Poland and immigrated to the United States when she was 16. She was short and plump and pretty with smiling blue eyes and curly red hair like little Aaron’s. She was too happy being in America to mind being poor. All she wanted was to keep her children as clean and as well-fed and as happy as she could. There were worse things in life than being poor, Mrs. Chwatt knew, and a mother’s love and freedom couldn’t be bought at any price.

In these surroundings, Aaron was a lively, jovial, energetic kid willing to do anything for a smile. Skinny and small, he never let his size bother him. What he lacked in stature he compensated for in heart and humor and leadership.

Wiry and muscular, he could hold his own in any brawl, and fighting was the number one sport in Aaron’s neighborhood, Third Street between Avenues A and B.

If the older, bigger boys challenged him to a fight and he felt he didn’t stand a chance, he’d tilt his head to the side, assume the plaintive facial expressions of a whipped dog and plead mournfully, “I ain’t got no mudder.”

It always worked. Nobody would hit a kid without a mother, for the only security those poor kids had was a mother.

When Aaron was about seven, his mother cut his bangs and substituted a long pants blue serge suit for erstwhile Saturday and Sunday best, a sailor outfit with white stockings and black shoes. The blue serge was his choir singing uniform, worn when his sweet, clear soprano voice rang out in answer to the Cantor’s chants in the local synagogue. If any fellow members of the “Rinky Dink,” his own block gang of which he was the undisputed leader, ever referred to his angelic face or singing in any but the most complimentary manner, they had the soprano’s fists in their kissers to prove he was no sissy.

When Papa Chwatt got a small increase in salary, he moved out of the lower East Side uptown to East 176th Street in the Bronx, so his family could be brought up in better surroundings.

In P. S. 44 in the Bronx, ten-year-old Aaron quickly established himself as a popular, versatile personality. He played on the baseball team, portrayed one of the frenetic leads in the school’s version of “The Katzenjammer Kids” and generally ingratiated himself with his teachers and fellow students. He would stop at nothing to keep his audience entertained.

His buddies, among them Arthur Brent, now a partner with Red’s brother Joe in the ABCO Hardware store in the Bronx, knew that Red had one peculiarity. He couldn’t pass up a mirror, whether in a store window, a livingroom or a washroom. Whenever he spotted a looking glass, he stopped whatever he was doing to peer at his likeness, not to admire himself but to distort his features into weird grimaces.

“Whatcha doin’, Aaron?” his surprised companions asked at first.

“Practicin’, just practicin’,” he answered without getting out of character. “If I’m gonna be an actor, I gotta be able to act.”

Muggsy Buttons, Rocky Buttons, Salty Buttons were conceived in a mirror. As Red watched the mannerisms and expressions of each one emerge before his very eyes, he also developed another characteristic. Shaking his finger at his mirrored reflections, he admonished them waggishly, “I like you. You, I don’t like.”

He wasn’t too engrossed in his career to be unmindful of the fair sex. The girls tagged after the cute redheaded jester, but his favorite was a long-legged brunette. They demonstrated their mutual affection by playfully throwing stones at each other in lieu of cupid’s darts.

Nothing but applause was hurled at the 13-year-old boy the night he appeared in an amateur contest at the Fox Cretona theatre a few blocks from his apartment house. When he sang “Roll On Mississippi, Roll On” and “Sweet Jenny Lee,” he brought down the house and won first prize.

His reward was a singing spot in the overture to the vaudeville acts. Nightly, for 15 weeks until the Children’s Society stepped in and stopped him, the slight, shining-faced, redheaded singer stood on a soapbox in the orchestra pit and in his good blue serge suit and budding alto bade the Mississippi roll on.

For a couple of years after the Children’s Society rang down the curtain on him, his only brush with show business was when he subwayed downtown and went to the Palace to hang around the stage door or when he climbed over the fence of the old Biograph Film Studios in the Bronx.

On one of these excursions, he met Bud Pollard, a Biograph film producer who took an interest in the boy.

“Show business isn’t easy, kid,” the older man advised. “You’ve got to work hard to get there. You need all the breaks you can get and then when you do arrive, if you’re one of the lucky few, the toughest thing is to stay on top.”

But how was a kid with no background, no real experience and nobody to help him, going to break into show business? That was Aaron Chwatt’s number one problem. No talent scout from Broadway was haunting the amateur theatricals of the Evander Childs High School. He couldn’t afford to take an ad in weekly Varietysaying “At liberty” so he did the next best thing. He answered an ad for a singing bellhop to work during the summer at Dinty Moore’s City Island Tavern. He was 16 and impatient to get his theatrical career under way.

One night he confided his ambition to a customer.

“What’s your name, kid?” the customer asked.

“Aaron Chwatt.”

“Aaron what? Thats no name for a comedian. You have to get something they’ll remember. How about Red? Your hair’s red.” The customer paused a minute and studied the serious face of the brass-buttoned bellhop. Then he snapped his fingers. “I’ve got it. Buttons. Red Buttons. That’s a name they’ll never forget.”

The newly christened Red Buttons realized that before people could remember his name they had to hear it. How? Where? When?

Soon, he hoped. Occasionally during the winter, he sang for free at parties given by his father’s co-workers. At one of these parties, Red met somebody who knew somebody who owned a hotel in the Catskill Mountains. The chain of hotels dotting the Catskills was known as the Borscht Circuit because good food, borscht included, was the chief attraction of these summer hostelries. The customers had to be entertained, too, but managements preferred to pay less to their entertainers so they could pay more to their cooks.

Red Buttons could be bought cheap. The Beerkill Hotel in Greenfield Park. New York, hired him as a singer at $1.50 per week plus room and board.

That was the life. It seemed too good to be true and midway in the season Red awoke one morning to find his worst fears justified. Something had happened to change his luck—and his voice. Overnight the boy alto had become a boy bass and there was no place on the program, he knew, for a singer with a crinkly smile and a crackly voice.

“They’ll fire me. They’ll fire me,” he worried. His desperation was readily apparent when he confronted the program director with his crisis.

“Don’t worry, Red,” the showman said, “the summer’s almost over. I’ve seen you make with the jokes. You’re pretty funny. Stay on as a comedian.”

Red didn’t find it hard to make the people laugh. He pretended the audience was his family and his friends. He always could make them laugh so why not these people who came from the same, warmhearted kind of background?

As the basis of his humor, he fell back on an exaggeration of his childhood experiences. He never wanted to be funny at anybody else’s expense. His cute pixie face, impish expressions and slight stature made his memories of the lower East Side seem incongruous and funny.

“Where I came from,” he announced, “anybody with teeth in his mouth was considered a sissy. In school they used to have recess just to carry out the wounded. We were evicted so many times my mother made curtains to match the sidewalks.” Then he’d swing into the swagger and gestures of Jimmy Cagney and the tough guy tones of Edward G. Robinson, the screen bad men of his youth.

Cupping his hand over his ear, he illustrated his alleged childhood miseries with “Oiy, oiy,’ and broke into a little dance. In time he was to change the “Oiy, Oiy” to “Ho-Ho” and add to it a musical introduction of more quips and patter, “Strange Things Are Happening.”

His third summer in the Catskills when he was 19, a burlesque agent touring the Catskills for talent caught Red’s act.

“Come see me after Labor Day,” he told the comedian. “I’ll give you a two-weeks’ trial at Minsky’s.”

Mr. Harold Minsky was no Charles Frohman or David Belasco but he was the number one producer of burlesque shows. The Misses Gypsy Rose Lee, Georgia Southern, Margie Hart and Ann Corio were his stellar strippers.

Frank Faye, Bert Lahr, the late Rags Ragland, Robert Alda, and Phil Silvers were among the graduates of the burlesque comedy school.

Opening night he was so frightened that in a sketch called “Get Out Of The Car,” in which he was to support a prop automobile, he was shaking so from stage fright that the automobile rattled in unexpected places, but rattled as he was, Red didn’t forget his lines or cues. His natural pace and timing helped him adapt himself quickly to the fast turns and blackouts of burlesque. In time he learned to “cut it,” burlesque lingo for making good.

His mother and father used to come down from the Bronx to the Gaiety at 42nd and Broadway to see him. Only a mother’s desire to see her son on the stage could have lured Sophie Chwatt into a burlesque house. When the strip teasers were teasing, Mrs. Chwatt buried her face in her hands. She only looked up—and cautiously at that—when her son, Aaron (she still calls him Aaron), was singing “Sam. You Made The Pants Too Long,” or doing some other such enlightening scene.

One of the proudest moments in Sophie’s life came when Al Jolson, in a box seat, applauded her son’s comedy. Afterwards the Mammy singer went backstage to see the young comic.

“You’ve got it, kid,” Jolson told Red Buttons. “Someday you’ll be a star.”

Stars and would-be stars have to live and love, too. Outside of his school time romance when he pelted his favorite girl with stones, Red had been so busy trying to carve his name in lights that he hadn’t given much time to romance. He fell in love, not with a girl from his old neighborhood, but with a stripper in the show. She was a tall brunette named Roxanne (not to be confused with the blonde Roxanne of television).

He was the most dazed and the happiest guy on Broadway when she said she would marry him. And he was the loneliest, unhappiest comedian in show business a couple of years later when she divorced him. The torch Red carried was bigger than himself. In the true Pagliacci tradition, he tried to lose himself in work; the Catskills, the night club dates, the one night stands, but in a sequence of bad luck events all the breaks seemed to be against him.

He was working in Margie Hart’s Wine, Women And Song when the censors banned the play and burlesque from New York.

In 1941, he had his foot in the legitimate theater when it was ousted from the door. José Ferrer had chosen him for the juvenile lead in a musical with a Pearl Harbor locale. The play was due to open December 8, 1941, but that was the day after Pearl Harbor was bombed and The Admiral Takes A Wife was blasted off Broadway before it got there.

He was set for a role in a James Cagney film but another actor got the part because he also got less money.

The day he was due to leave for Hollywood and a Paramount movie, his draft notice showed up. It looked like the end of everything for him. According to the accepted movie tradition, his worst break proved to be his best. In the Army, Moss Hart picked Red for a lead in the Army Air Force musical production, Winged Victory, and later the comedian also appeared in its movie version.

In 1945, the khaki-clothed comedian emceed a show at the Potsdam Conference before Harry S. Truman and Winston Churchill. They agreed unanimously that Private Red Buttons was funny.

When he got out of the Army, he knew he could always earn a good living, at least $500 a week or so, with his nightclub routine, but he still hearkened back to those days as an East Side kid when Broadway was his dream. He wanted to be in the bigtime. In order to do so, he took a salary cut to appear in the plays Barefoot Boy With Cheek and Hold It. His notices were better than the plays’ notices.

Back he went to his old faithful, the club dates and theaters. In the winter of 1949, he was playing a nightclub in Miami Beach, Florida. A petite black-haired girl with the elfin features of a Leslie Caron, Helayne McNorton from Ohio, was working as a manicurist in a Miami hotel. She saw the comic work and said to herself, “I’d like to know him.”

After the show when Red came out front to sit with some friends, Helayne did meet him. They exchanged hellos and she realized he hardly noticed her, but she didn’t forget about him.

That summer, she was in Lindy’s restaurant in New York one evening and was re-introduced to Red. They exchanged hellos again but with little recognition on his part. Several nights later, they met once more in Lindy’s. This time Red said, “Doll face, I’ll drive you home.”

There were other people in the apartment Helayne shared with her roommate and they made scrambled eggs and coffee for the late visitors. “I’ll help you do the dishes, Doll face,” Red offered. It was the first and last time he dried the dishes, but for Helayne, once was enough. Red Buttons was the boy she wanted to marry.

“How about meeting me tomorrow night at Toots Shor’s?” Red suggested. Helayne had met actors before. Sometimes they didn’t show up for dates so the next night on the pretext of being delayed, she called Shor’s and asked for Red. To her surprise, he was there.

“I’ll be right over,” she told him. She fell in love with him that night. Her future was Red, she was sure. She knew he had been hurt deeply by the failure of his first marriage and that he didn’t want to get burned twice. She was willing to wait.

Early in their courtship, she broke other dates to be with Red. He was somewhat serious offstage. He didn’t joke and clown as much as when he was a kid but his ad libs were fast and furious.

When he questioned Helayne once about breaking a date she disarmed him with her straightforward reply, “I’d rather be with you.”

“Why waste your time with me?” he said, “I don’t want to get married.”

“You will,” she countered.

Three and a half years ago they were married.

They lived in an apartment in the West 50’s within shouting distance of Broadway. Helayne went to cooking school so she could wield the pots and pans with as much agility as Red dished out his humor.

Last fall they signed a lease on an expensive five-room apartment on exclusive Sutton Place, just 51 city blocks north of the East Side tenement where Aaron Chwatt was born.

Then television, which devours talent like a hungry tigress, wanted new stars. Red Buttons was a comparative unknown outside of New York and Florida, but Marlo Lewis, a CBS-TV variety show producer, realized the capabilities and potentialities of the versatile comedian, who was 33 but looked 23.

Red was anxious to try the medium. It was his only chance for national recognition. The movies wouldn’t hire him because he wasn’t known so TV offered him the culmination of a dream.

“Where did this kid come from?” everybody wanted to know after his sensational debut. He had something in his act for everybody, an appeal that got to all kinds of Americans. Within a few weeks, the “Strange Things Are Happening” routine swept the country. Audiences chimed in and home viewers chanted, “Ho-ho, hee-hee, stra-a-a-ange things are hap-penning.”

Up in the Bronx on East 176th where they have lived for the past 24 years, Michael and Sophie Chwatt didn’t think there was anything strange about their son’s success. Their boy, Aaron, had to make good because he was good. He never hurt anybody. He just made them laugh. He was kind and generous. Every winter since he could afford it, he has sent his parents to Arizona for the cold months because the desert air is good for Mrs. Chwatt’s asthma.

A darling, dimpled, plump version of her son, Sophie’s story, too, is a success story. An immigrant at 16, she raised a boy who became an American Horatio Alger. When she goes to the grocery store or the neighborhood stationer’s to buy a birthday card, the tradespeople point her out, “That’s Red Buttons’ mother,” but for Sophie the greatest thrill is always her frequent visits from her second son, her Aaron, who says, “Hi, Ma,” and kisses her.

Up in the Bronx, in brother Joe’s hardware store, the school kids flock in to ask Joe to have Red autograph pictures for them. “Ho-Ho,” he signs, “Red Buttons.”

In her river view apartment on Sutton Place, Mrs. Red Buttons (he legally adopted the name) doesn’t think it’s strange that success in a bigtime way has come to her husband. He always went out of his way to help other entertainers, she knew. And Red was due for the big break.

She and Red wish they had some little Buttons tearing loose around the house. Monday nights after his TV show, and after he has had a masseuse limber him up after his strenuous shenanigans, the comedian takes his wife to Lindy’s where they sit around like old times and chat with the other comics, Milton Berle, Jack Carter, Phil Silvers, all local boys who made good.

Over at CBS-TV Red Buttons puts in long hours each week. He’s too busy preparing for Monday to stop and marvel at all the strange and wonderful things that have happened to him. Because to Red Buttons, every Monday is Opening Night.

THE END

—BY JOAN KING FLYNN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1953

No Comments