Elvis Presley Takes Hollywood

“I’d sure like to take a crack at it,” Elvis Presley was saying. “I know I could do it easy.”

The thing Elvis thought he could do “easy” was portray the life of the late James Dean on the screen. Elvis sat back on his haunches as he was kneeling in front of us on 20th Century-Fox’s huge recording stage, confiding his latest ambition to me and Dave Weisbart, producer of Presley’s first picture, “Love Me Tender.” Weisbart was also the producer of “Rebel Without a Cause,” which starred Jimmy Dean, and he had come to know Elvis better than anyone in Hollywood. He agreed with Presley’s optimistic wish. “I’m sure,” said Dave, “that Elvis could do a good job of portraying Jimmy.”

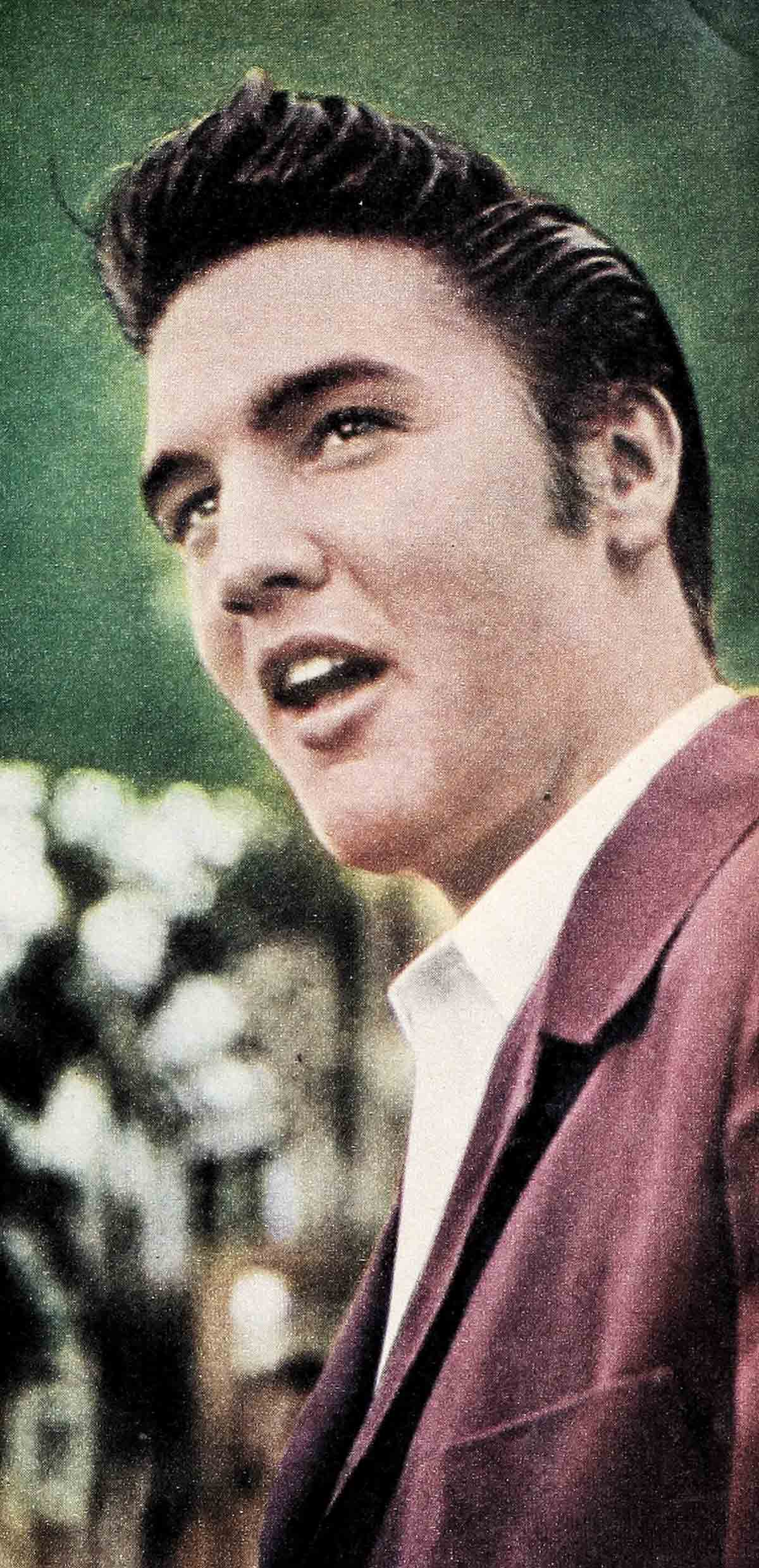

Elvis had been sitting in an awkward position for several minutes, with no apparent discomfort or pain. His legs were bent up under him, yet his spine was straight. His head was slightly tilted, and his right arm was folded across his chest, his hand holding his left elbow, his left hand thoughtfully stroking his smooth chin. He chewed nervously, unconsciously, on some chewing gum.

“I think I could do it easy,” Elvis repeated. He was still on the subject of filming Dean’s biography. “I want to play that more than anything else.” Then he shook his head, as if to bring himself back to the present and to the fact that he was capturing Hollywood just as he’d captured every audience he’s ever faced.

It was the first day of work on “Love Me Tender.” Elvis had started out by explaining to producer Weisbart, almost shyly, “I don’t know much about this business, so I learned the whole script—everybody’s parts.” He smiled, and his smile, too, was shy, almost ashamed.

Elvis’ fingernails were worn ’way down. He ground them nervously as he stood in the recording room. He had no guitar to hold onto. He noticed the pianist had left, and he walked over to the piano, sat down, and started pounding out a boogie beat. At first it was rusty, then it picked up and became quite good. Elvis should have been taking it easy—the recording session was still ahead of him, and he hadn’t eaten any lunch. Oh, yes, he’d had a cup of coffee, if you could call it that—the cup was half-filled with cream.

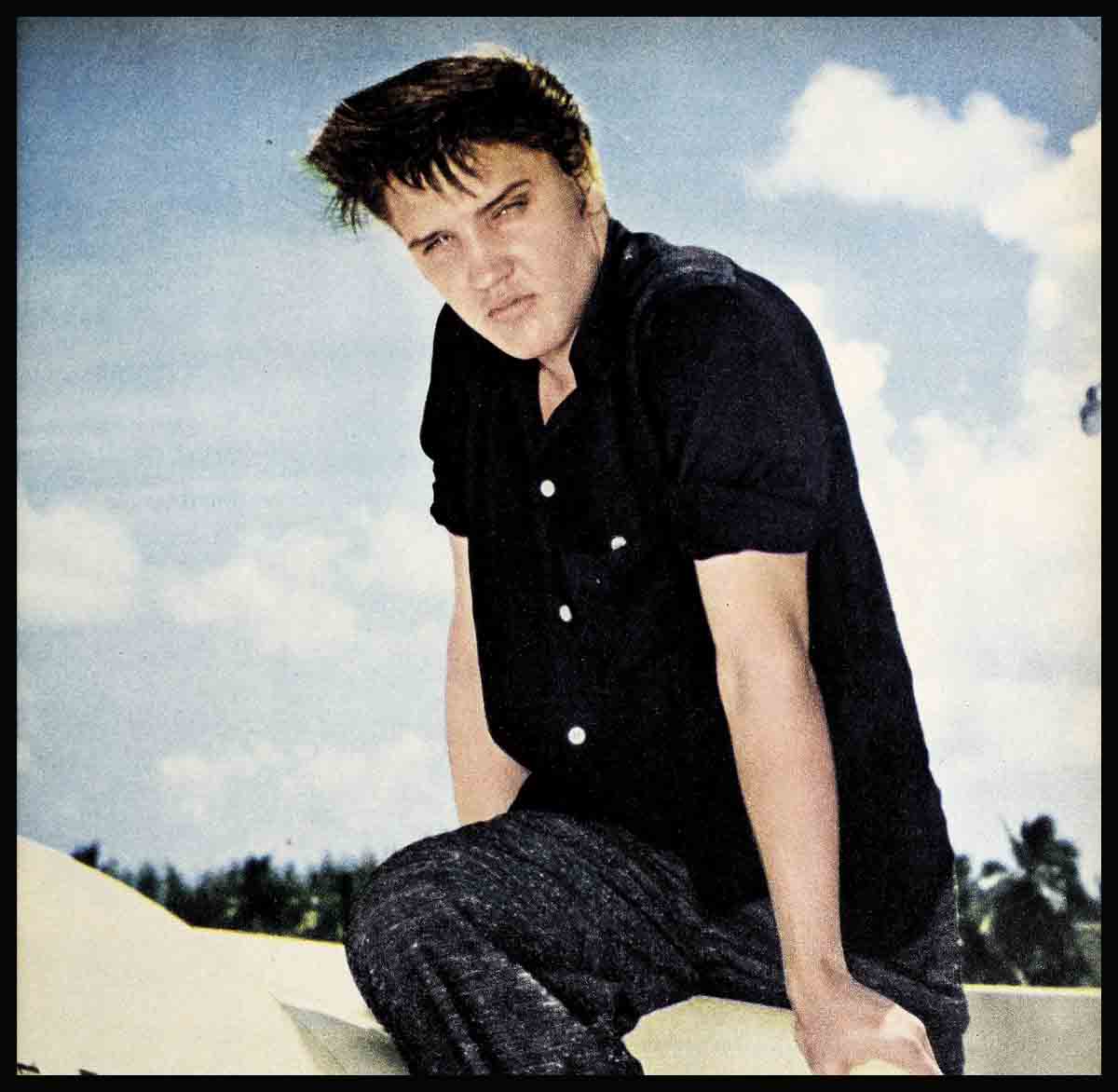

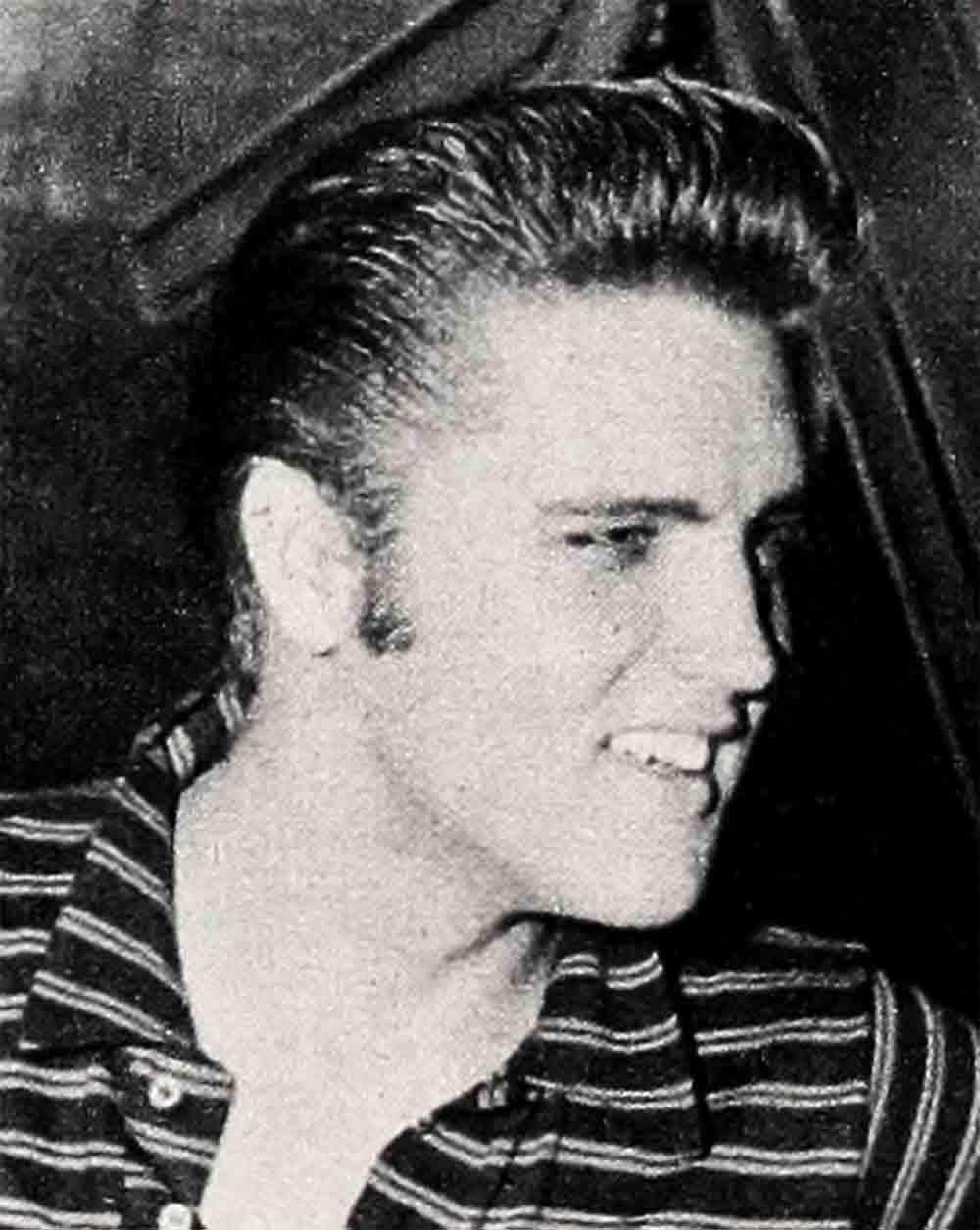

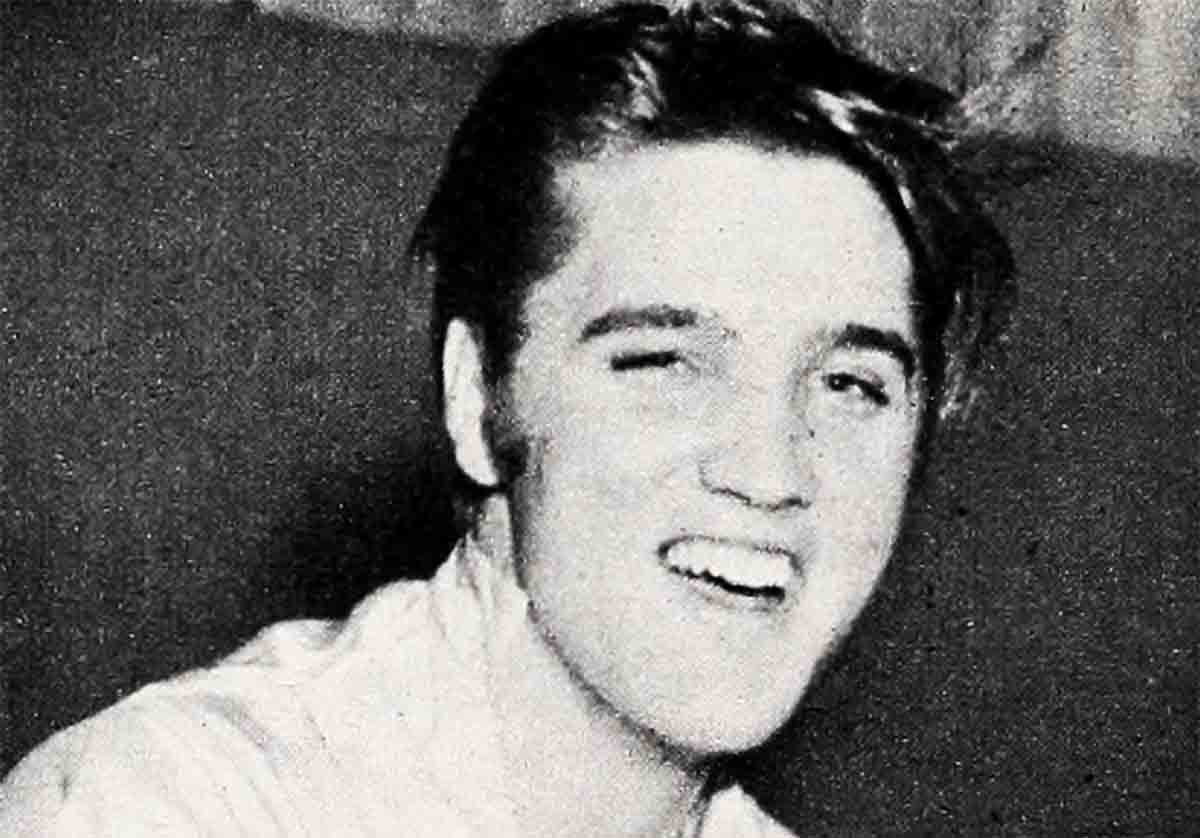

HERE ARE YOUR ELVIS PRESLEY PINUPS

“He only eats when he knows he should eat,” his manager, “Colonel” Tom Parker, informed us.

During Elvis’ first week on the 20th lot, we heard nothing but raves about him from the studio policemen, secretaries, fellow actors and actresses, right on up to the top producers. There hadn’t been this much excitement on the lot since Tyrone Power was the big new threat.

By contrast, when Jimmy Dean was new at Warner Bros., the report that went cut about him was, “What a character we’ve got over here. He acts like a sloppy pig and dresses to match.”

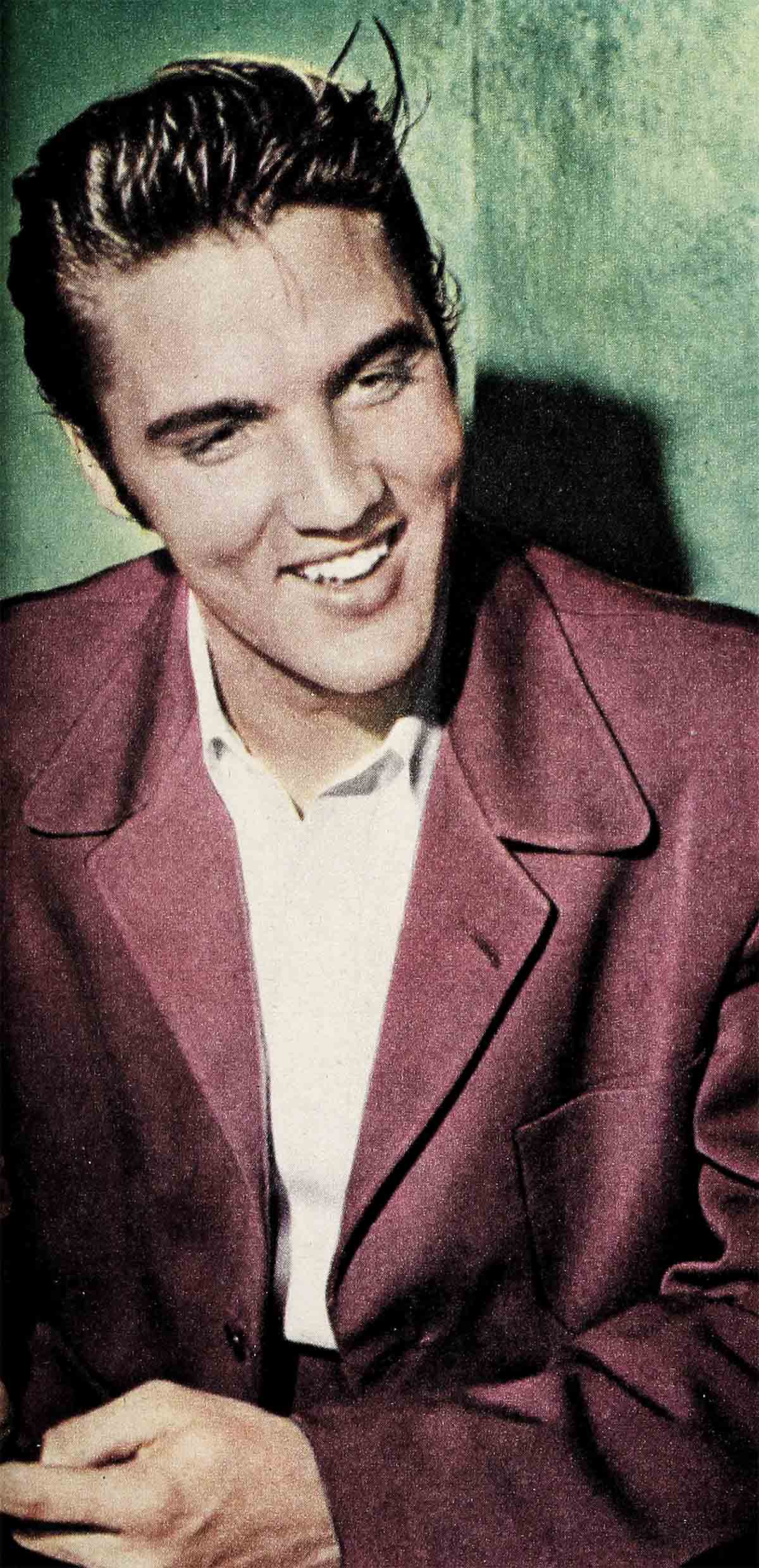

Elvis is the opposite. When we saw him, he was wearing black and white shoes, brown slacks, and a pink satin shirt, cut like a doctor’s or barber’s jacket. A fan, he confessed, had made it for him.

“How about this!” he laughed. “Isn’t it something? I look like a doctor in a Technicolor hospital!”

Elvis, who doesn’t smoke, reached for another stick of chewing gum and stared rather moodily off in another direction. Then his attention came back to the present again.

When we asked him whether he could explain Jimmy Dean’s great following, and what phenomenon caused that following to increase after Dean’s death, Elvis had a ready reply.

“I think they believe that he represented them,” he explained. “He acted like them, and he acted for them. He was today’s youth, he shared their problems, their likes and dislikes. At least he did so more in ‘Rebel’ than in ‘Eden.’ ‘Eden’ had more specialized problems. When he died—well, they mourned him for themselves even more.”

And what about Elvis’ success? Is it due to the same phenomenon which caused Jimmy’s success?

“Gee, I don’t know. All those movements I make seem to mean so much hem. I don’t really know what it is that causes it to happen. Sometimes, when I’m up there on stage, I might just close my eyes a minute, real tight, or bite my lip, and that does it to them. I might put my hand up hard against my forehead, or maybe reach down and straighten my pants cuff or rub my ankle, and they scream. I just don’t know what it is. But it seems natural.”

The musicians—two guitarists, a drummer and a pianist—returned from their “break.” Ken Darby’s trio took its place at one mike and Elvis went over to another. They were ready for a take. The red light went on at the stage door, music conductor Newman counted “one-and-two-and-three,” and the music started beating. Elvis got the downbeat from Darby and started singing “There’s a Leak in This Old Building.” He kept the beat with his body, slowly moving back and forth. There was no hand-clapping, foot-stomping, or finger-snapping. Elvis moved slowly, his arms leading his long, wiry frame, back and forth in tempo. It gave everyone the urge to rock with the beat, to clap hands with the tempo. Even the walls were aching to shake. When the number was completed, all the crew clapped hands. Every face wore a smile.

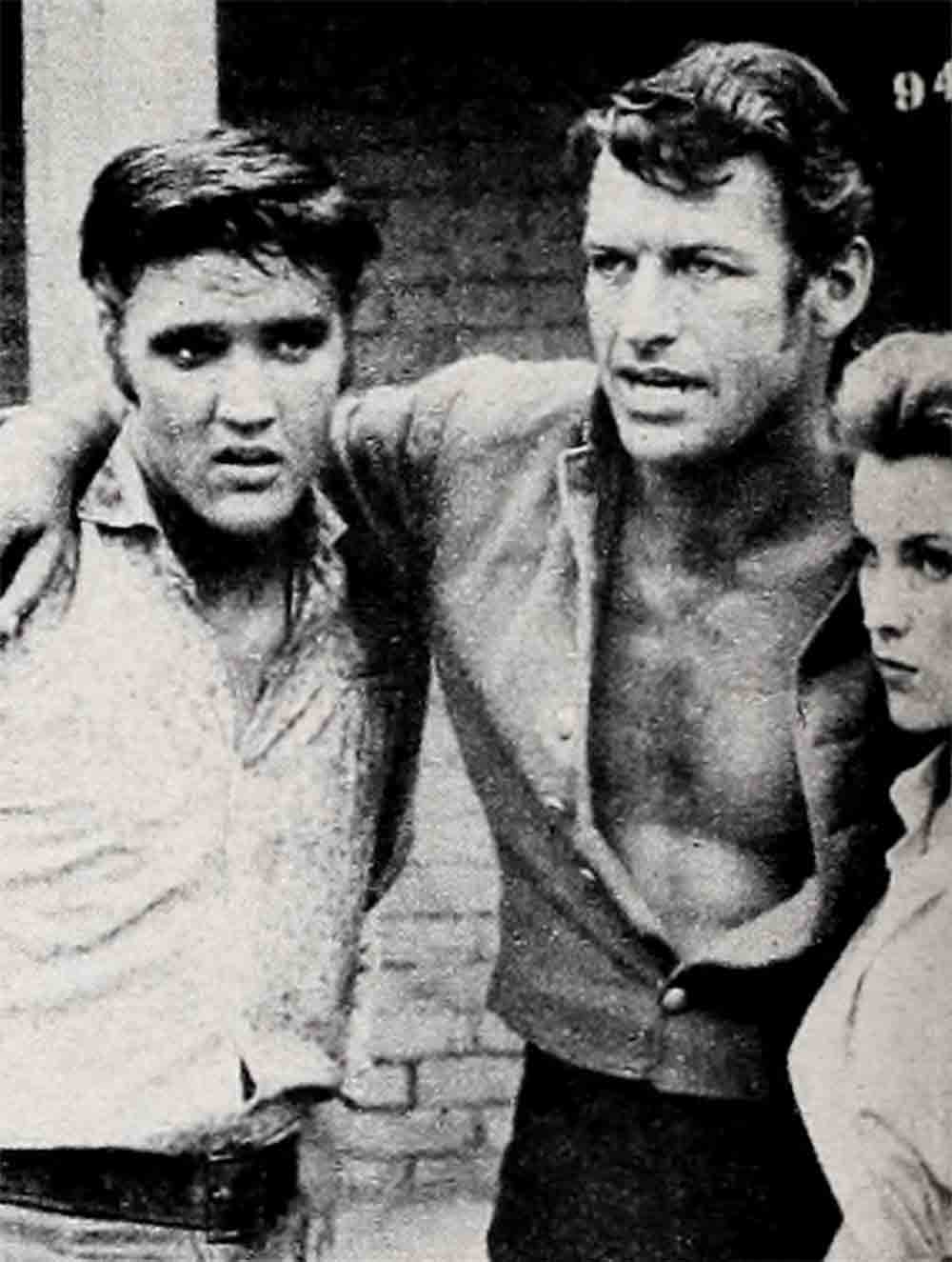

Then Ken Darby asked the boys in the booth to play back the recording. Elvis stood nervously in a corner of the stage, waiting. He noticed a couple of boys in another corner who had been quietly watching and listening. Their faces were tense, too. They were Nick Adams, who had been a good pal of Jimmy Dean’s, and Dennis Hopper, also one of Jimmy’s buddies, who does a great job in “Giant.”

Elvis went over to them, said “Hi,” just as the playback cue thundered through the huge stage, which was sprinkled with only a handful of humans. Everyone was motionless with anticipation. Elvis strained to urge the first note from the mammoth loudspeakers.

Nick and Dennis listened—and they looked. They looked at Elvis as if he were someone they knew, someone they had known before, perhaps.

The number ended and everyone agreed it would be a natural top-seller. Elvis went over to Ken Darby to discuss changes for another take.

Nick Adams, wearing his usual saucy hat, was acting as serious as we’ve ever seen him—off-camera, that is.

“You want to know what kind of guy Elvis really is?” he asked. “I’ll tell you.”

Nick proceeded to give us the story of how, a few days earlier, Cameron Mitchell had pulled out of Elvis’ film. Cam had been scheduled for a supporting role, as one of the “heavies” in “Love Me Tender.” Nick didn’t know why Cam pulled out, but he did know one thing—it would be a great role for himself. We could have told Nick that Cam was mad at the studio for giving him a secondary role, especially after RKO had offered him a starring role which his 20th bosses had turned down.

It’s no secret around town that Nick’s a go-getter, and he went after the part by beating the ‘bushes in the front offices at 20th. While roaming through these “badlands,” Nick bumped into Elvis. And before Nick knew what had hit him, Elvis was saying: “Gee, I think you’re a swell actor.”

It didn’t take Nick long to tell Elvis how much he’d like to be in his film. He told Elvis how he’d played a “heavy” in “The Last Wagon.”

“Gee,” said Elvis, “I’ll tell Mr. Weisbart to look at ‘The Last Wagon.’ ”

Weisbart, at Elvis’ request, went to see the film. Although he finally decided Nick was too young for the role, the point Nick had to make about Elvis was: Here’s a guy who’ll go to bat for you at a moment’s notice!

Dennis Hopper winked to us, “I’m going to start singing soon, too. And I’m not kidding—I’m taking lessons.

The biggest surprise about Elvis and his singing had been revealed to us earlier, when he gave us a private concert. For the first time (professionally), he sang a soft, ultra-slow ballad He invited us over to the quaint music bungalow on the far west side of the 20th lot. It was away from the bustle of traffic and from the big stages. It looked like the kind of cottage Walt Disney would have built for Snow White and Prince Charming. This was where Elvis felt relaxed, comfortable.

Ken Darby sat at the grand piano at the far end of the living room. Elvis stood a few feet behind him, and in front of a tall, stained-glass window. He stood erect, as if he were in a choir.

Ken started to play the soft melody. I hardly knew that Elvis had started to sing, as his voice, barely louder than the piano, was saying: “Love me tender. . . .”

His voice was pitched slightly higher than in his usual rock ’n’ roll tunes. It had a lot of resonance, vibration, and Elvis was on-key for every note, no matter how long, short, high or low.

The expressions on his face were kind and lacked any of the familiar exaggeration of his mouth, eyes, or shaking of his head. He sang each word with the meaning he (and Mrs. Ken Darby) had written into it. When he finished, it seemed only normal to express our amazement.

“People think all I can do is belt,” he said. “I used to sing nothing but ballads before I went professional. I love ballads. I love to sing slow, but seldom get to do it.” He continued to explain that as a boy, an only child, he would sing like that when he trioed with his mother and dad in church. “It was a small church,” he explained, “only seated about 75. You couldn’t sing too loud, there.”

Elvis plans to sing the slow numbers on his next cross-country tour, to prove he’s a singer, as well as an entertainer He was glad that the title of his first film was changed from “The Reno Brothers” to “Love Me Tender.” The latter identifies it more as a story which Elvis. “Reno Brothers” would made it sound like a Western.

Richard Egan, by the way, plays Elvis’ older brother in “Love Me Tender.” The story takes place in the Deep South in 1865, just after the Civil War, and tells about two brothers. Elvis plays the role of the younger brother, who does not go to war. Dick Egan, who plays the older brother, does go to war and is believed to have been killed. During the war, Elvis falls in love with Debra Paget and marries her. His family doesn’t tell him that Dick had planned to marry Debra before he was “killed.”

We don’t want to give away the story, but be forewarned that Elvis, in his first movie, is killed. However, he a valiant death and for a worthy cause.

“I was plenty scared that first Elvis admits His honesty was well-founded, for he had never done a lick of acting. “Not even in school,” he says.

Dick Egan, remembering how tough it was to get started, sort of took Elvis under his wing. “This is a fine, honest boy,” Dick told us.

When Elvis confessed, “I how to read lines at all,” Dick laughed and said, “Don’t think about reading lines. Don’t worry about being an actor. Just go out there and be yourself. Be natural—be Elvis Presley.”

There had been a lot of discussion about “coaching” Elvis in acting. Perhaps someone should be hired to teach him the fundamentals. Perhaps someone like Natasha Lytess, who took another phenomenon, Marilyn Monroe, and made her into an actress.

Director Robert Webb and producer Dave Weisbart had considered this, but they also had hoped Elvis would display enough natural acting ability to get by without coaching, which, in turn, might bury his unique appeal. So they held out against getting him a coach until after they could see how he looked in the “rushes.”

As soon as the first film came back from the laboratory, Webb and Weisbart dashed into the projection room, viewed Elvis’ first scene and decided: no coaching. At least, not as long as he continued to handle the scenes and lines that well!

Ben Wright, the film’s dialogue director, was assigned to go over lines with Elvis before “takes,” but this was not out of the ordinary. Every film’s star does the same thing, if only to be sure he knows his lines—and sometimes the right day’s work!

“One of the best ways to describe Elvis,” Dick Egan smiled as he watched him walk into the commissary, “is just to say he’s a real nice fella.”

Elvis had been equally, if not more, impressed by Egan, and appreciated Dick’s assistance in giving him self-confidence. As a matter of fact, Elvis was impressed by everyone at the studio who had literally given him the A-1 welcome treatment. Having been an only child, he especially enjoyed the camaraderie, the friendly feeling in making films.

We asked Elvis if he had any favorites in movies. “I love ’em all,” he smiled. “But I’ve got one special gal. And she’s the only gal for me. But she keeps me 64.000 miles away.”

Who, we asked, could this gal be?

“Debbie,” he smiled. “Debra Paget.”

Later, in the commissary, Elvis and his cousin Gene Smith, with Colonel Parker, were at one table, and Debra, her mother and sister were at another. When Elvis was called away for a few minutes, we sat down with Debbie.

“What’s this about cold-shouldering Elvis?” we asked.

“What!” Debbie exclaimed.

We explained.

“Oh, that,” she laughed. “Well, there are all sorts of ways to travel, and 64,000 miles is pretty far! Actually, I’ve known Elvis better than anyone here, because of the Milton Berle TV show we were on together. And I’ve done the spadework here, preparing everyone for him—and I mean to let them know what a nice guy he really is.

“However,” Debbie added, “I’ll admit that my impression of Elvis, before I met him, was the same as many others who don’t know him. I figured he must be some sort of moron. Then I met him—and believe me, this boy isn’t. The best way to describe his work, I think, is to say it’s inspired.”

Colonel Parker is quick to kid about anything he and Elvis do in terms of dollars and cents. We noted one of the studio press agents was wearing an Elvis Presley fan club button, and we asked when and how we could get one.

“We’ll have to check you over,” Colonel Parker said. “It’s not that easy, you know—to get the fifty-cent buttons. Besides,” he laughed, “if we make it too easy, no one will want to get one.” Elvis made no comment, nor did Elvis’ cousin, Gene.

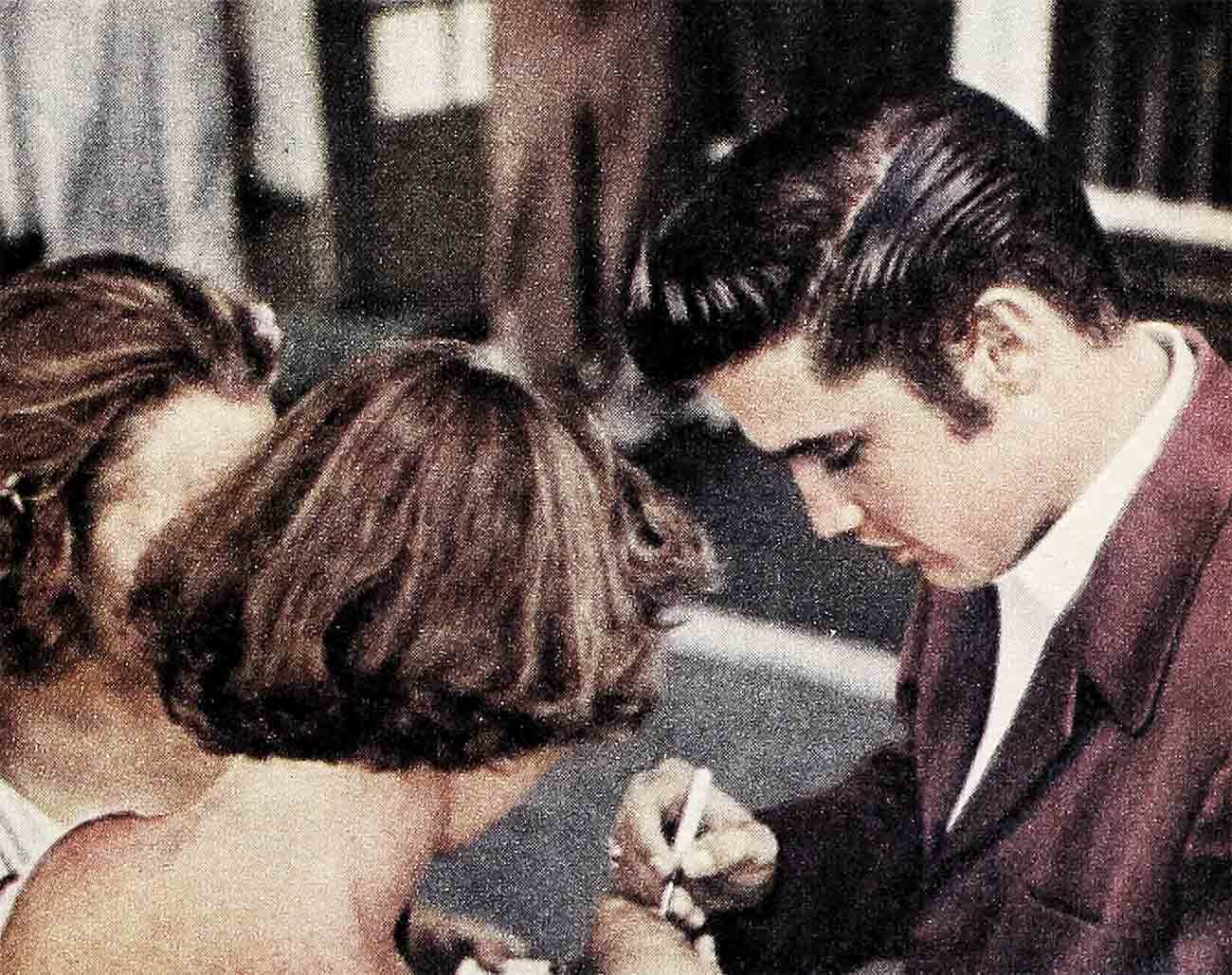

A studio visitor, probably the daughter of an important theatre owner, came into the alcove where we were eating. She wanted Elvis’ autograph, but she was so nervous, she couldn’t say anything, just giggled. She stuck a pen and piece of paper in front of Elvis. He smiled at her, signed his autograph, and thanked her, without putting her to any embarrassment.

The studio commissary hostess came in and said there was a phone call for Elvis from New York. He was set to answer it when the studio press agent checked, found it was a fan calling, and stopped it. Then he issued an order to stop the calls in there.

If all the calls for Elvis were put through to his office on the lot, his secretary (he had to hire one while at 20th) would do nothing all day but pick up phones. When it became known that Elvis was staying at the Hotel Knickerbocker in Hollywood, there were 237 phone messages for him at the end of the first day!

The studio workers, who were used to seeing every top star in the business, found themselves saying such things as: “I was certainly very big at my house last evening when I told my daughter I saw (sat next to, or heard) Elvis on the lot yesterday.”

Up to this point, Elvis had maintained his complete humility and appreciation of what had happened to him. For example, when Ed Sullivan was hurt in an auto accident, one of the studio men thought it would be nice if Elvis sent him a note, along with a picture taken at the studio. Elvis autographed the picture to “Mr. Ed Sullivan.”

Elvis had a strange introduction to Movietown. The young man with the many expensive cars arrived in Hollywood without any car—and right in the midst of a taxi strike. So he found himself being chauffeured around town, and to work each morning, in a 20th Century-Fox limousine.

Having been brought up in a Tennessee farm community, Elvis took no chances about relying on his experience to ride a horse. He headed out to “Fat” Jones’ ranch in the San Fernando Valley, and got his spine accustomed to the saddle, instead of his Cadillacs. Of course, he didn’t overdo it. The horse he rode was “Old Jim,” who has been “breaking in” movie stars for over fifteen years, and who knew just how gentle to be.

Elvis also kept in shape with his favorite pastime—tossing baseballs at milk bottles at a near-by amusement pier. On his first Saturday night in Hollywood, he had headed for the Long Beach amusement park and had won seven stuffed teddy bears before the crowd recognized him. P.S. He returned to the hotel with none of the prizes!

His collection of stuffed animals—mostly “hound dogs”—increases daily. In fact, there is no more space for them in his hotel room. However, judging from his future film schedule, Elvis will probably buy a mansion in Bel Air big enough for all his dogs, stuffed and otherwise. Because Hollywood’s verdict on Elvis is that he’s here to stay, and he has signed up for three pictures in all. He gets $100,000 for his first, $150,000 for his second, and $200,000 for his third. After that, Elvis has confided to friends, he and Colonel Parker plan to form their own production company.

All in all, Elvis is a “real nice” boy with a real cool head on his shoulders, and he’s taken Hollywood the way Grant took Richmond—leaving the “enemy” outnumbered, out-flanked and unable to say anything except, “Nothing like it has happened before.”

Chances are, nothing like it will happen again, either!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1956

No Comments