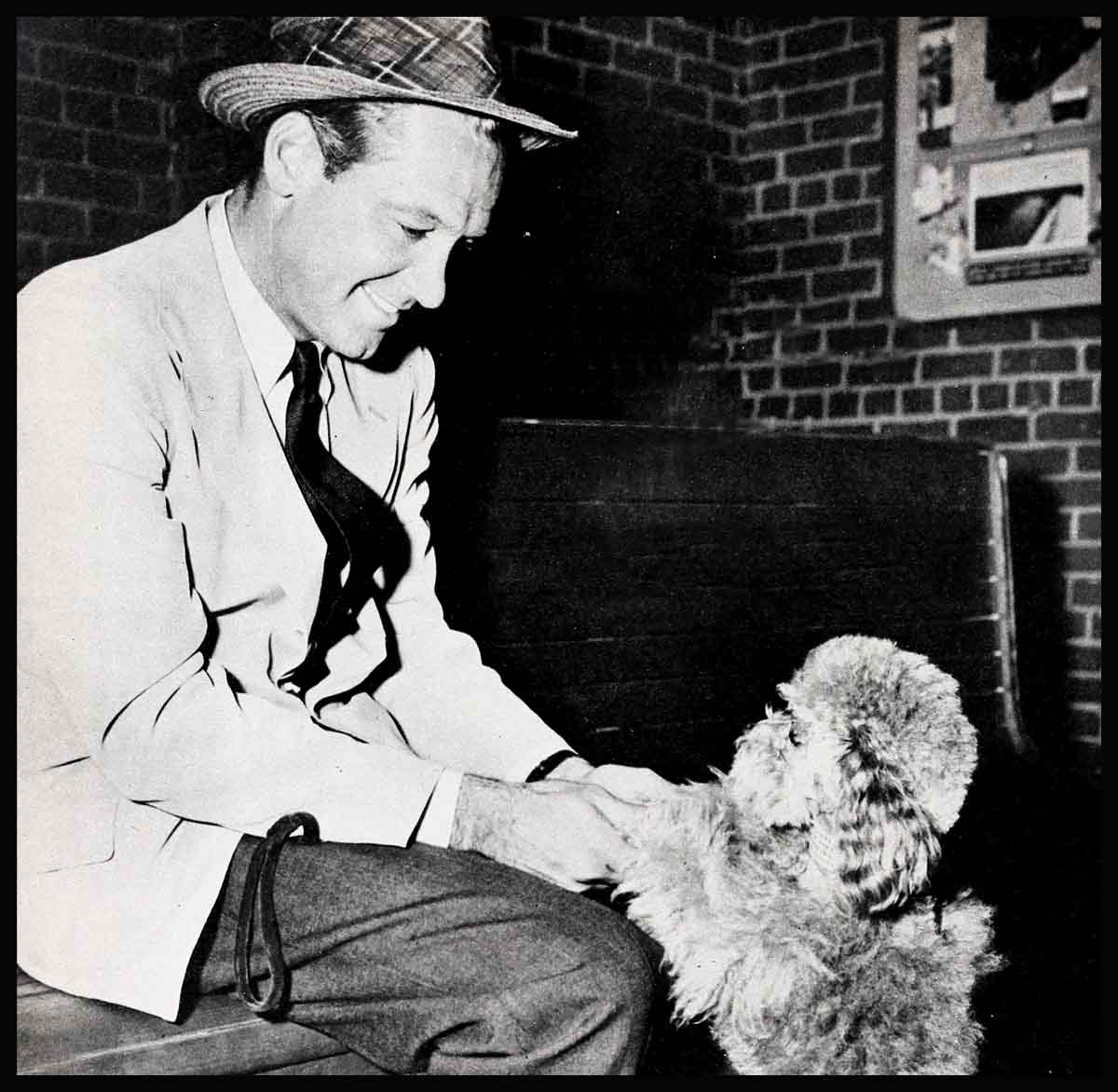

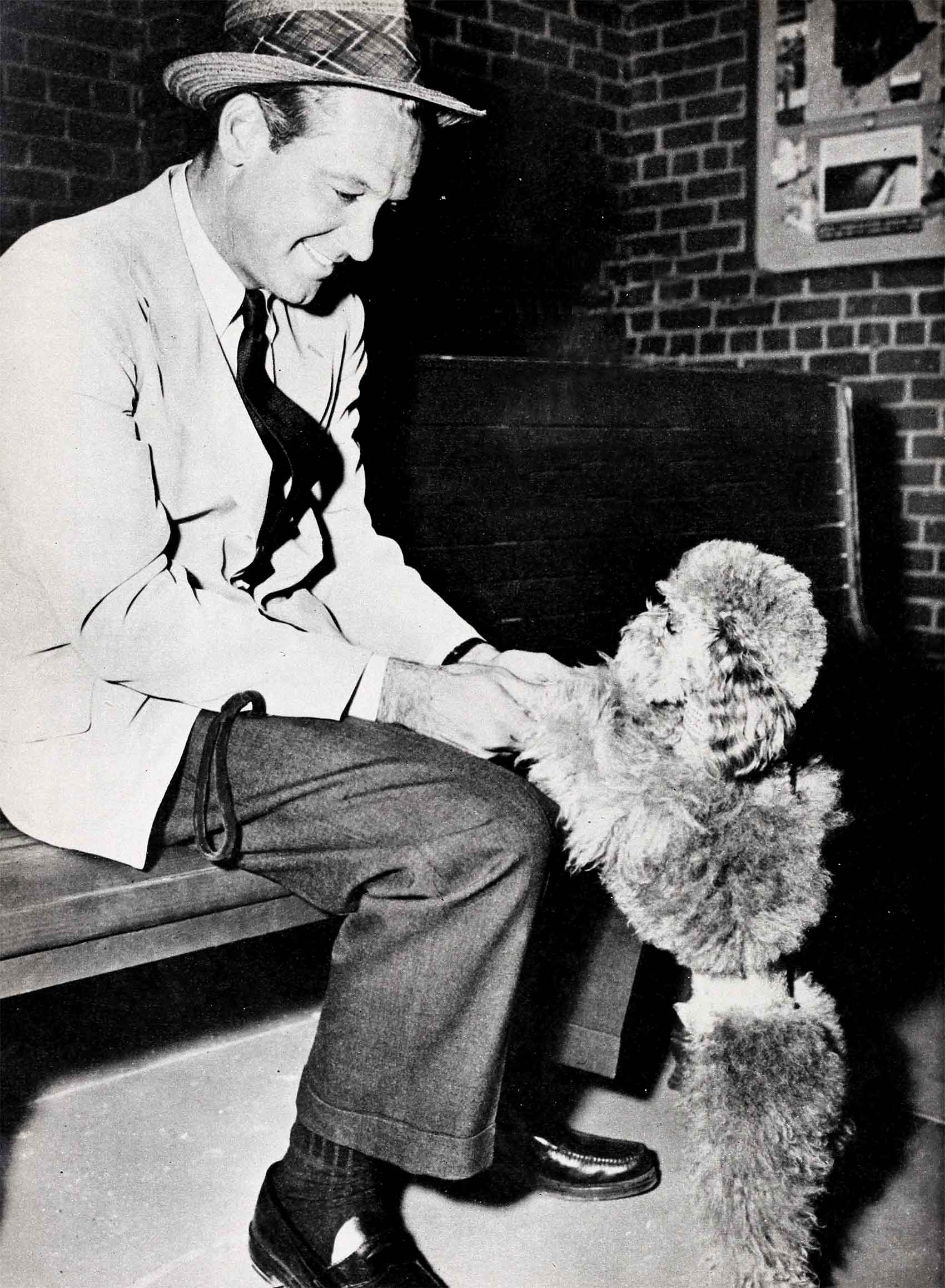

The Guy With The Grin—William Holden

Ardis and I try,” Bill Holden once remarked to an interviewer, “to lead a sensible sort of life.”

Now, the idea of trying to live sensibly is one which simply wouldn’t occur to some Hollywood stars. Live glamorously, live excitingly, live dangerously—yes. But live sensibly? Who wants to? Sounds dull.

The Bill Holdens don’t find it dull at all. For them, it is a richly satisfying way of life.

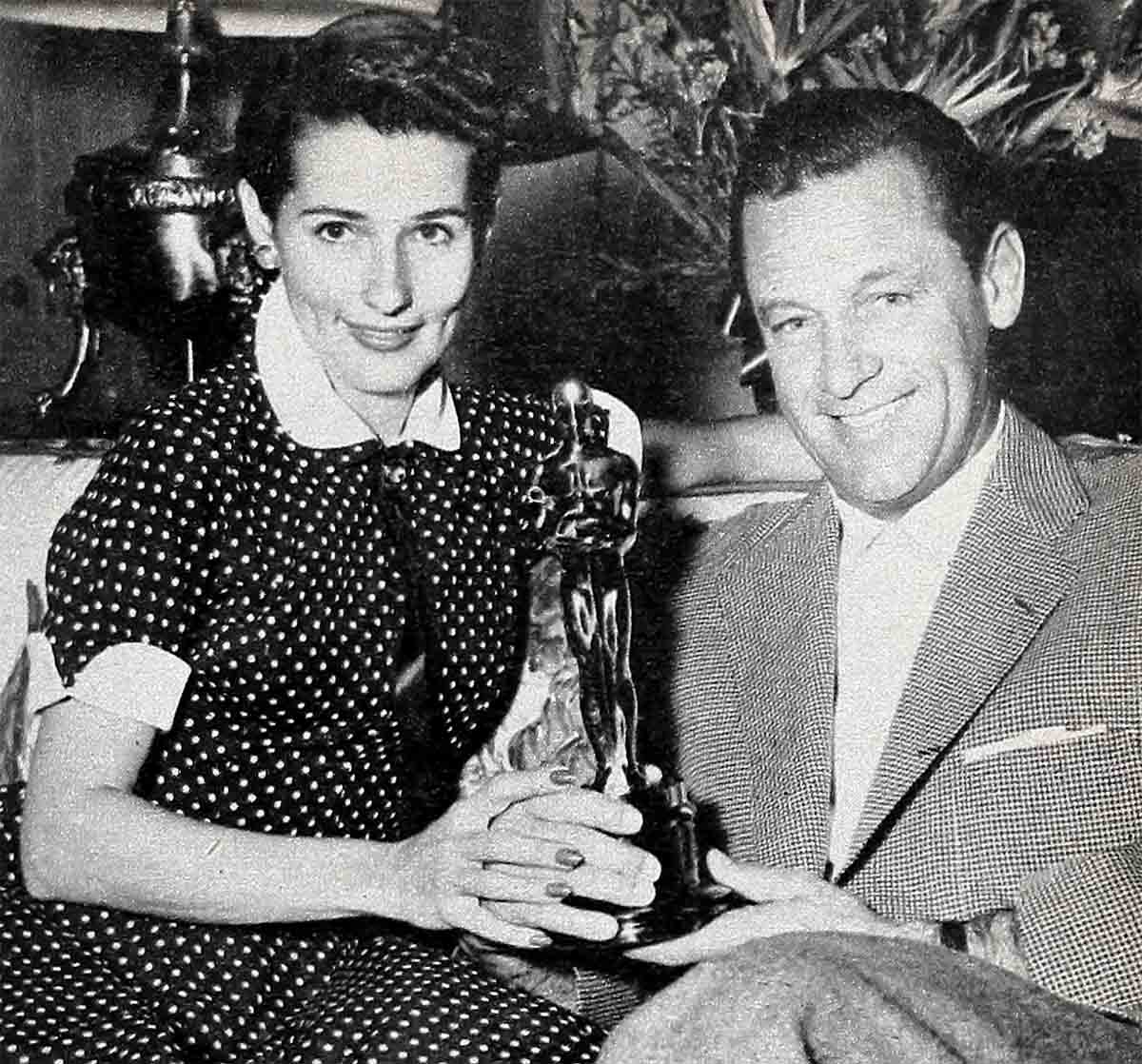

The Academy Award winner, star of “Executive Suite” and the soon-to-be-released “Bridges of Toko-Ri,” and his beautiful wife celebrated their thirteenth anniversary last July 13. Theirs is one of Hollywood’s good marriages. In this world, of course, nothing is certain, but it would be hard for anyone who knows these two at all well to doubt that they’ll be together to celebrate their 23rd and 33rd and—God willing—their 43rd anniversaries just as happily.

Not just because they are still in love. They are, but marriages have been known to crash while the two principal parties were still deeply in love. Especially is this true in Hollywood, land of temperament and ego. Nor are Bill and Ardis, whose professional name was Brenda Marshall in the days before she gave up her acting career, lacking in these self-same qualities. But they do, both of them, have the emotional maturity to realize that lasting happiness doesn’t drop into your hand like a ripe peach from the tree, but must be worked for, planned for, even sacrificed for.

They’ve done all three.

It was back in 1939 when Bill Holden and Brenda Marshall met. Bill was twenty-one, and it was barely a year since he’d crashed stardom with his first picture, “Golden Boy.” Handsome and talented, he was getting the standard treatment for promising newcomers. Luscious young starlets and more firmly established stars, so long as they were unattached at the moment, were willing and even eager to be dated by him.

Bill would have none of them. He was, for one thing, working to the very limit of his energies. Overnight, he had been plunged into an acting career. He not only had a lot to learn—he knew he had a lot to learn. Even then, there was a deep vein of seriousness in him; even then, he loved acting for acting’s own sake and wanted to be good at it.

He had a good friend, a man named Hugh McMullan who had been dialogue director for “Golden Boy.” Hugh and Bill shared a small house in the Hollywood hills, and Hugh used to worry, mildly, because for Bill life consisted of so much work and so little play. One after the other, pretty girls that Hugh knew were invited to the bachelor quarters for dinner. Bill was polite, he was friendly, but he wasn’t interested.

He was even less interested when Hugh mentioned a young actress named Brenda Marshall whom he’d known in New York, and who was now in Hollywood under a Warner Brothers contract. For Brenda was in the process of securing a divorce from her first husband, actor Richard Gaines, and she had a baby daughter. Bill Holden wasn’t complicating his life by having anything to do with a married woman—no sir!

But Bill went to the Warner Brothers lot, on loan, to star in a picture called “Invisible Stripes,” and it happened that Brenda visited the lot one day to see her friend Jane Bryan. She and Bill were introduced, chatted awhile—and that was that.

“I thought he was very nice—and very good-looking,” Brenda confesses today. Bill says more forthrightly, “I couldn’t forget her.”

He tried, for about three months. Then he gave up, and called Brenda late one day. “If you’re not busy tonight—?” he suggested, and Brenda, with visions of a romantic twosome in some discreetly lighted night spot, averred that she was not at all busy. “Then I’ll come around right away. They’re shooting some night battle scenes for ‘The Fighting 69th!’ I thought you’d be interested in watching. We’ll pick up something to eat on the way.”

Oh well, Brenda thought. If that’s the kind of guy he is—And she chose something serviceable and washable to wear on the dusty location spot where a World War I battle was being restaged.

They had their romantic evenings later. But they also had horseback rides and badminton games, hunting trips and swimming expeditions, in rather greater number. Bill is a good dancer, and enjoys dancing. He just doesn’t enjoy it quite as much as the more strenuous forms of physical activity. He soon learned a healthy respect and admiration for Brenda’s skill in these pursuits, and for her knowledgeability about sports in general.

Bill and his Ardis—he never called her Brenda, and does not now—didn’t rush into marriage. They were married twenty-one months after their first meeting, in Las Vegas. It was not a very romantic elopement, sad to say. Bill was working and could get only the weekend off. So he chartered a plane for a Saturday night flight, made arrangements by long-distance telephone for the Congregational minister to meet them in his chapel at 10 P.M., and reserved the bridal suite at El Rancho Vegas.

Both Bill and his best man, Brian Donlevy, were held up on the set for some overtime shooting, so the plane was behind schedule when it left the ground. Halfway to Vegas, they ran into bad weather and had to land on a muddy emergency field and go the rest of the way by hired car. It was three in the morning when the bridal party limped into Las Vegas. The minister had gone to bed and the hotel had given the bridal suite to another couple.

Bill was discouraged but not daunted. He roused the minister, who performed the ceremony in a hotel room at four a.m. “Then on Monday I went back to work while Ardis moved our things into the new house we’d bought for the honeymoon we couldn’t have. Because on Wednesday she left for three weeks on location in Canada. By the time she came back, I’d gone to Carson City on location for my own picture. I left Carson City suddenly, in an ambulance which took me to the Cedars of Lebanon hospital for an emergency appendectomy. The day before I was to be released, she began getting pains in her left side. The doctor took a look at her, and the next thing either of us knew she was being wheeled into the operating room to get rid of her appendix. Some honeymoon!”

But that wonderful Holden grin robs the last two words of any bitterness.

It is a matter of sober fact, though, that Bill and Ardis had very little chance to get to know each other in the early years of their marriage. It was July, 1941, when they were married, and in December of that year the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the nation was at war. Bill completed the picture he was making for Paramount, and then, on April 17, he enlisted in the Army. He was in the service until after the war had ended—November, 1945, to be exact.

Those who knew him in the Army say that Bill Holden was a good soldier. He asked for no favors, plainly expected none. After basic training, as he became eligible, he applied for admission to Officers’ Candidate School, was accepted, completed the rugged course of advanced training there and was commissioned a first lieutenant in the Air Corps Training Command. He took the assignments that came his way and did the jobs he was told to do, submerging his own individuality, his own hopes and desires, melting into the organization that was the Army. When sent overseas, he gave no outward sign either of relief or of disappointment. He simply obeyed orders “for the duration,” filling administrative posts at training fields.

He behaved, in fact, not like a famous Hollywood star but like the son of William and Mary Beedle, two ordinary, unglamorous Americans.

Bill Holden was born William Beedle, Jr., in the small town of O’Fallon, Illinois. His father was a young chemist, his mother was a school teacher. Both are people of character, and early in Bill’s life they began the task of building character in their son.

One thing they taught Bill—perhaps, he thinks today, the most important thing—is that there can be no privilege without an accompanying responsibility. The young Bill had plenty of play time and fun, but he always knew that in order to pay for his enjoyment he must do certain chores. He remembers an occasion when he rebelled against attending Sunday school because it was a heady spring day and he wanted to go fishing. Sunday school in the Beedle family was a must, but Mrs. Beedle did not scold, neither did she threaten. She merely remarked that Bill could certainly skip Sunday school if he were willing to skip the movies next Saturday. Bill saw the point, as he was to see it many times in his formative years.

When Bill was five, the family moved to Monrovia, California. There was a younger brother by then, and a year or so later a third was born. The Beedles prospered, modestly, until the nineteen-thirties, when the depression hit them at the same time that Bill’s father was laid up with pneumosilicosis, an illness which kept him bedridden for three years. Bill, at twelve, became the man of the family, caring ‘for his father, his two brothers and himself while Mrs. Beedle took up her profession of teaching once more.

“Bill was wonderful,” Mrs. Beedle says today. “Many a night I’d come home, tired and worried, and find that the three boys had the house spick-and-span and dinner started. Bill would pull out my chair at the table and seat me as if I were visiting royalty. We.didn’t have much to laugh about in those days, but we laughed just the same.”

Mr. Beedle recovered, happily, the depression eased its grip on the nation, and there was money for Bill to attend Pasadena Junior College, with an eye to following in his father’s footsteps as a chemist. Chemistry did not particular inspire him, but in his late teens he didn’t know exactly what would inspire him more. Without seriously believing he could ever act professionally, he was active in college dramatics, and it was while he was playing the role of a seventy-year-old man at the Pasadena Playhouse that a Paramount talent scout saw him and was—to put it mildly—impressed.

“Any green kid who can convince me he’s an old man—there is an actor!” the scout reported to his studio superiors.

Artie Jacobson, head of talent at Paramount, sent for Bill and offered him what any other twenty-year-old would have jumped at—a screen test. “We’ll shoot it a week from now,” Jacobson said briskly. “Every day until then, report here at the studio for coaching.”

But Bill shook his head regretfully. “I can’t, Mr. Jacobson. We’re having finals all next week and I can’t skip classes and risk flunking out.”

It wasn’t, you see, that Bill didn’t care about the test. He did care, passionately. But he had a responsibility to his parents, who had made certain definite sacrifices to send him to college. By great good fortune, Jacobson was wise enough to recognize character when he saw it. He arranged for Bill’s coaching to take place at an hour every day which would not interfere with final examinations. Bill passed the examinations with flying colors, took the test, and was given a Paramount contract at $50 a week.

Ordinarily, this would have meant nothing but a bit part in a Paramount picture—or not even that. But William Perlberg, preparing to produce “Golden Boy” at Columbia and searching for a girl to play the sister, asked Paramount to let him see the test made by one of its starlets. It happened to be Bill’s test too, and when Perlberg had seen it he telephoned Paramount excitedly: “You’ve found our Golden Boy!”

It happens that way sometimes. Not often, but sometimes. In one enormous leap, William Beedle, unknown, became William Holden, playing the title role in an important picture. But always, along with the privilege, went the responsibility. Bill plunged into work harder than any he’d ever known—rehearsals, boxing lessons, violin lessons, voice lessons, coaching sessions. Now, if ever, he learned the value of the self-discipline his parents had made part of his nature.

He learned it again during his days in the Air Corps. Enlisting when he did, he had interrupted his career at a crucial point. He was known in Hollywood as a promising young leading man, but he hadn’t yet become firmly established as a star. His earnings had not been great. He left behind him a young wife and a stepdaughter, Ardis’s little girl Virginia—and early in 1943 it became apparent that Ardis was going to have another child.

Bill and Ardis had talked about this—planned for children, hoped for them. They had agreed that when Ardis became a mother she would retire from the screen completely. Their conversations had taken place before Bill enlisted, but the changed circumstances didn’t alter their decision. Before Peter Westfield Holden was born on November 17, 1943, Brenda Marshall abandoned her career—for good.

It was a considerable sacrifice. As the war went on, Ardis and Bill found they had to watch the pennies very carefully in order to make ends meet on his Air Corps pay. And when at last the war was over and Bill was discharged, they learned that the few months’ delay between V-J Day and his November discharge date had been crucial. Hollywood had already recovered from its wartime shortage of leading men. Although Bill was still under joint contract to Paramount and Columbia, there seemed to be nothing for him to do. For eleven months he sat around, apprehensively wondering if he’d ever act before a camera again.

“All the time I was in the Army,” he said later, “I was well adjusted. But when I got out, if ever there was a time that I doubted myself, that was it. I was supposed to go right into ‘Dear Ruth’ but they kept postponing it. Instead of the feeling of freedom I had counted on having as a civilian, I didn’t know what to do with myself. For eleven months I was a fugitive from a psychoanalyst. I was short-tempered, moody and depressed. I avoided all my friends.”

It was a simple case of jitters—of being afraid that he was forgotten, finished, as an actor. He needn’t have worried, of course. “Dear Ruth” was finally made; it was a smash hit; and from there on Bill went on to greater and greater successes.

Today the Holdens live in a roomy Georgian house with a flagstone front and four bedrooms. They bought it shortly after the birth of their second son, Scott Porter, in 1946. In it, they lead a relaxed kind of life—a sensible life. They night-club very little. Their closest friends are the Ronald Reagans, the Richard Carlsons, the Glenn Fords. Any or all of these couples are apt to drop in on a Sunday afternoon when, as is well known, the master of the house will be found presiding over the barbecue grill.

Bill loves to cook, and he loves food. Not as to quantity—he doesn’t eat a great deal, as a matter of fact—but as to quality and variety. “It fascinates me,” he says. “I even like to read about it.”

Another of his enthusiasms is shooting. He has his own gun collection, comprising eleven rifles and nine pistols, which he lovingly cleans and cares for himself. He enjoys classical music and ballet, but not opera—it’s too artificial for his matter-of-fact taste. He has a healthy self-respect, which once led him to go on suspension rather than take a role he didn’t like, and an equally healthy modesty, which keeps him working and studying to perfect himself as an actor.

Ardis, he says simply, “is my right arm. When Ardis gives me advice, I take it. She’s always right.”

And somehow you feel that Bill Holden wouldn’t consider it very sensible to treat his wife as anything less than a full partner in his life, to be respected and consulted . . . and, of course, loved.

THE END

—BY DAN SENSENEY

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1954