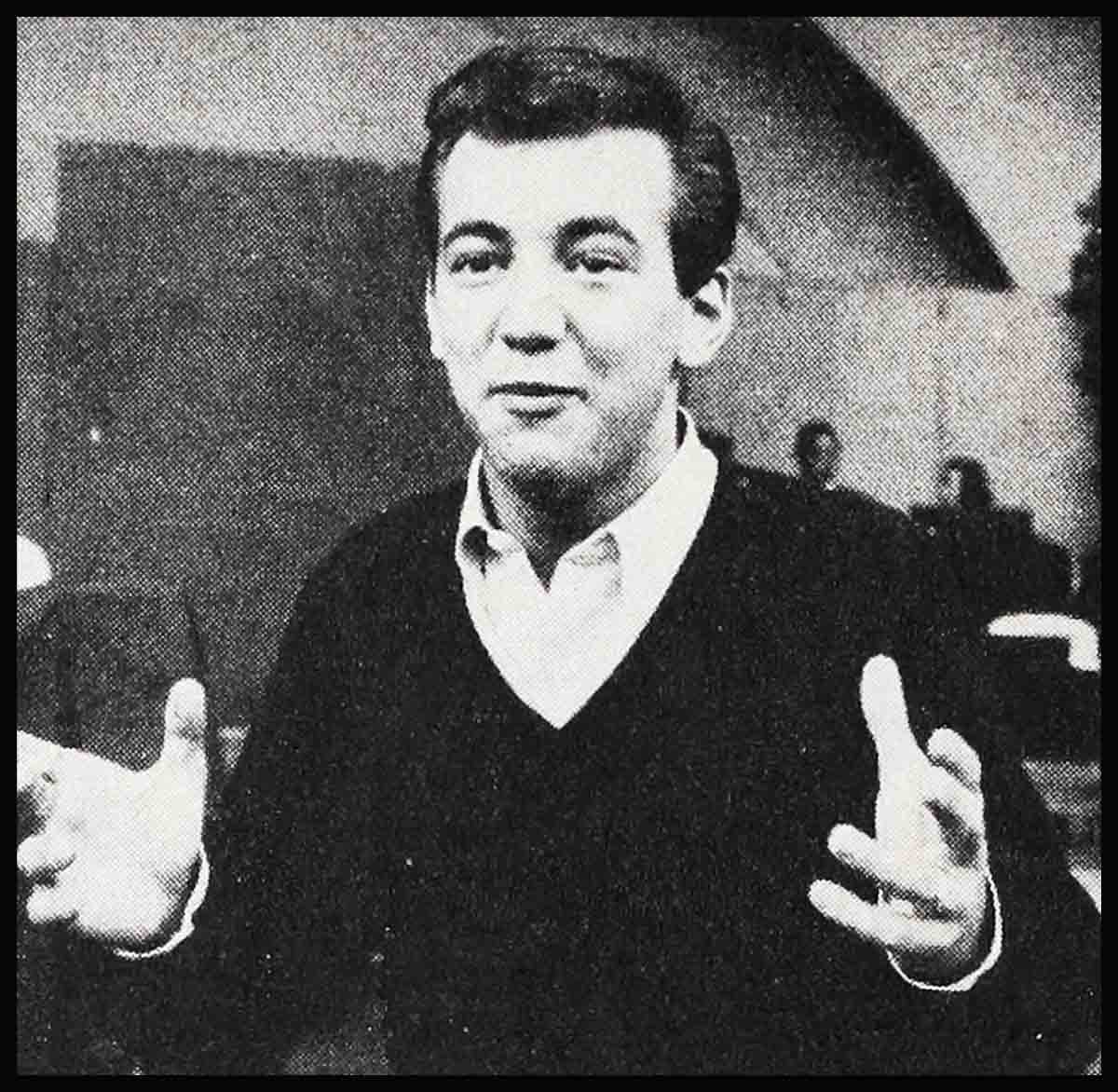

A Big Splash—Bobby Darin

“Splish Splash,” a Bronx matron said.

“Okay,” said Bobby Darin. He was used to the friendly dares of his friend’s mother. “I’ll write a song around that. Why not?”

It took him twelve minutes.

Bobby clears his throat, straightens his shoulders and then, taking off on an old-time songwriter, says, “And then I wrote . . . What he wrote is:

Splish splash, I was taking a bath

Long about a Saturday night

Splish splash, I jumped back into the bath,

How was I to know there was a party going on?

We were having lunch, catered by a nearby drugstore, at the offices of Csida-Grean Associates, the firm that acts as Bobby’s managers. Bobby, age twenty-one, was on the office couch, an elbow propping up one hand and his chin cupped in it. The rest of him was spread out full-length—five nine and a half, to be exact. From time to time he’d twist around just enough to take another bite out of his ham and fried-egg sandwich. “My mother sang in vaudeville,” he said, “although she never talked much about it. I never had any lessons in music. When I write something like ‘Splish Splash’ or ‘Early in the Morning,’ somebody else has to actually write it down.

“I’m very excited about what’s happened with these songs. But I’ve been here before. That’s where I started, at the top. My very first ‘pro’ job was with Tommy Dorsey. Nothing happened. I wasn’t ready. Nothing ever happens if you’re not ready.”

Bobby swung around to a sitting position and ran a hand through his hair. “You know, it’s kind of wonderful, the way people reacted to ‘Splish Splask.’ I loved the way the teenagers reacted to it. In fact, I love teenagers, maybe because I feel I never was one. But the fact is, I love everybody.” He stood up, did a little dance step and then went into a four-bar take-off on Perry Como singing “I Love Everybody.”

“Well, it’s true, I really do love people. And I’m very happy they liked the song. But that’s only one of my voices. People tell me they can listen to any song I might sing and spot something that marks it as me. I can’t. I try to sing every song differently, ‘cause every song is different. I’ve got lots of voices, kind of like a multiple personality. Maybe I’m a boy in search of a voice. In fact, I used to do voices of other singers. If a songwriter had something he thought Como would be good on, I’d sing like Perry on a demonstration record so that Como could hear how he’d sound if he ever decided to make a recording of the song.

“It got sort of confusing,” he admitted, “because a singer has to worry about almost unconsciously copying other singers. You have to stick to your own style. I’m lucky enough to have what’s called a natural ear. That’s why I’ve shied away from music lessons. I’m afraid they might spoil it. And that’s why I hardly ever go to see other singers. Without knowing it, you can pick up little things that other singers do and you hurt your own style. Professionally, I’m a doer. I learn singing by singing; I learn to play different instruments by playing them; I learn song-writing by writing songs. Privately, though, I’m an observer and not a doer.”

Bobby was back on the couch now, perched on its edge and leaning forwards. “It’s not that I don’t go out and do things. I like golf and fishing and sitting around with friends talking about just everything—everything, that is, but shop. But on the big things, I’m an observer and not a doer. It’s not my time yet to ‘do.’ When it is, I want, for example, to be a good parent. Now I just watch other guys who are fathers. I figure we can learn so much from other people, just by watching them. We can learn from their mistakes. Maybe I can’t learn what to do, but I sure can learn what not to do.

“When it’s my time to ‘do,’ I want to do it well. I like to do everything best. Like high school. I came from a poor neighborhood, so I decided to go to the Bronx High School of Science. That was the best school. I guess I wanted to balance things, a good school against a bad neighborhood.

“That’s really my philosophy, to keep a balance. Somehow, I’ve never felt that I belonged anywhere, so I guess I’ve tried to make up for it by doing things best. My sister was so much older than me that I grew up almost like an only child. I wasn’t lonely, but I just didn’t belong. I guess that that’s where I got what the psychologists—and I believe in those men—might call a complex, a confidence complex.

“When did it start? Well, I couldn’t have explained it then, but I think that what you are at twenty or so, you were at seven. It’s all there, just depending on which way it’s going to be developed. Even at that age, I knew I was going to make a career in music and that I was different. I didn’t belong. Well, you start with a feeling that you’re inferior and you come out with a confidence complex to make up for it. You start thinking, I’m not good enough for this world. And that leads to, I’m too good for this world.”

Bobby stood up and started to pace slowly, up and down the small office. “I know I’m inferior. I tell myself that eighty or ninety times a day. But the one time a day that I tell myself I’m a genius makes up for it, balances it. I think, What am I doing here? Then tell myself, Who cares, make the most of it. But then I can’t help thinking, Where did I come from, where am I going?

“It’s the sort of confusion that happens to people who ask questions. A scientist can solve it for himself by making the world less unhappy, perhaps by inventing a cure for some terrible disease. A religious person can find the answers in his religion. Well, I have no answers. I believe in God, but that’s it. I have no other formal beliefs. If He put me here, why did He put me here? That’s what I’m here to find out.”

Bobby brooded a moment over his paper container of Coke, then gulped down the last of it. “Till I find out,” he said, “I guess I’ll keep my shell on. That’s the coward’s way out and I know it. But I’m afraid of being hurt. I was hurt real bad when I was eighteen. It wasn’t her fault. She was older and it was a mixed-up relationship all the way. Still, I got hurt and I’m keeping out of emotion’s way right now.

“Maybe that means that if I don’t drop the shell, I’ll never be happy. Well, I’m having a lot of fun and I don’t really ever want to be happy. Not, at least, happy in a contented, self-satisfied way that keeps you from growing. I always want to want things.”

Bobby was grinning again and half-dancing on the walk through the busy music-promotion offices. At the door, he winked. “Don’t forget I’m a genius.” Then, in a whisper, cupping his hand over his mouth in mock secrecy, “But don’t tell anyone.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1958