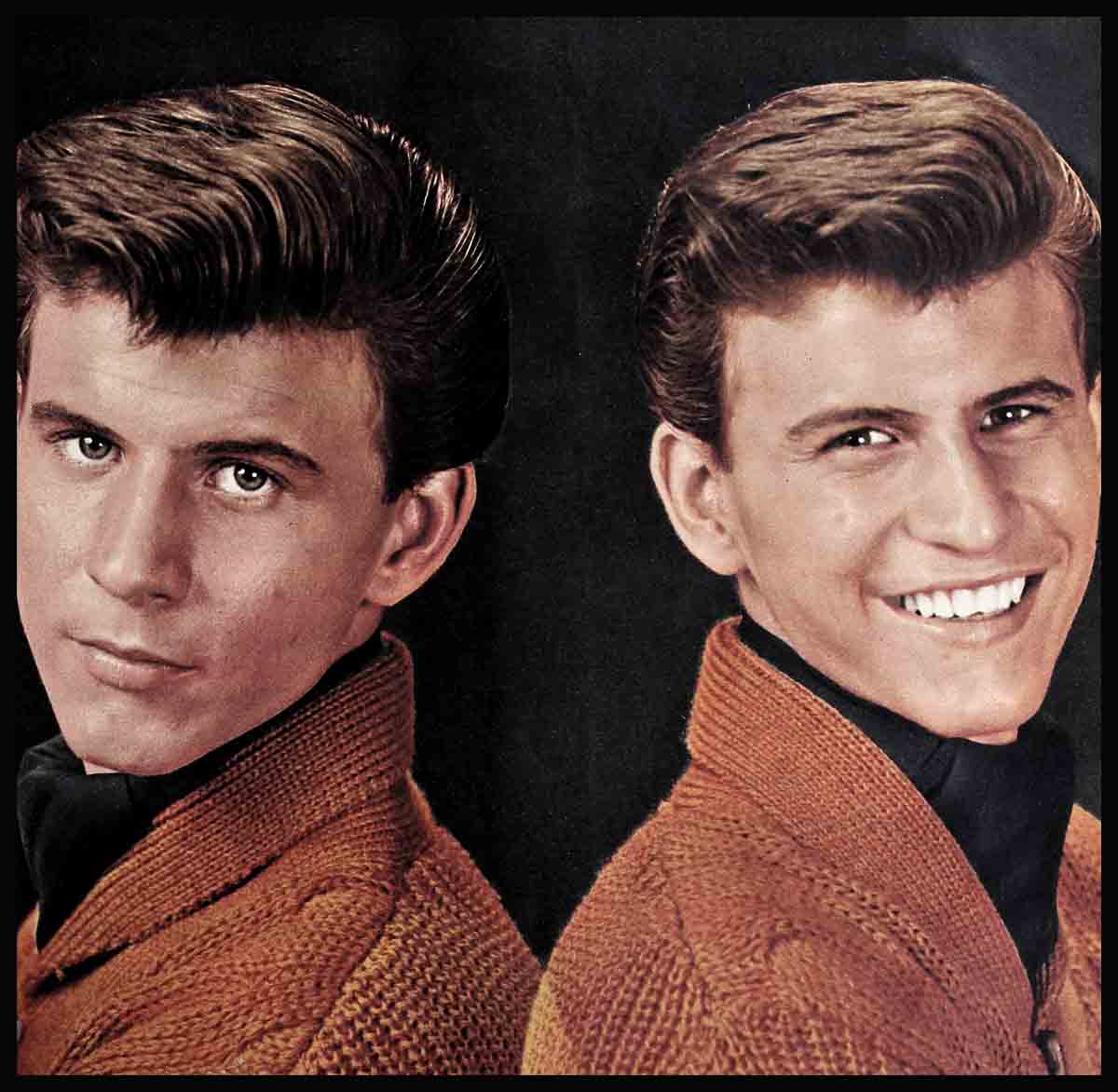

Bobby Rydell

It’s like a puzzle. You know the picture you’re supposed to end up with. Eighteen . . . five-feet-nine . . . a wide, crooked grin . . . a shock of blondish hair—the biggest pompadour in Hollywood. Somehow it doesn’t work out. Some of the pieces are missing. Like the way one minute he’s like electricity and the next, without warning, the switch is turned off. Like that pinky ring he never takes off—and never talks about either. Like the fire-engine red vest he bought and then hung away in the back of his closet. Like the girl he dropped so suddenly. What gives? He’s just a simple guy. You think you know him, but then you look twice and you wonder: Who is he? Sometimes even his mother doesn’t know the answer. “From one extreme to the other,” she’ll murmur, looking puzzled.

Like the red vest. It’s a toss up which is loudest, the red vest in his closet or the canary yellow one or the suit with the big checks—or maybe the apricot suede shoes. The boy loves bulky sweaters and neat tapered slacks, so he walks into a haberdashery and goes hog-wild among the racks of their flashier garments. He came home lugging his loot, and for an hour he tried on one outfit after the other for the family, pleased as punch with himself. Then spent the next twenty-three hours chewing off his nails. Suppose the kids think he’s gone high-hat?—the last thing in the world he wants to be. But maybe they won’t like it. So the dazzling new clothes went way to the back of the closet. Eventually some of them were dragged out again to wear on stage.

“Bobby’s a wonderful boy,” his mother will tell you, “but he’s a bundle of contradictions.”

He’ll say “Ah, gee, Mom, I’m not hungry.” But put a heaping plate of his grandmother’s ravioli in front of him and he’ll plow through it, ask for more—and more. He’ll eat like it was going to be his last meal on earth—and still weigh the same hundred twenty-five pounds he weighed yesterday and last month. He’ll drink five milkshakes a day (on a day he isn’t very thirsty) and still have to take pills to gain weight. A hundred twenty-five pounds, sure—but ten of them are his hair.

Bobby Rydell—the skinny little Ridarelli kid from the same Italian neighborhood in Philadelphia where Fabian grew up, and Frankie Avalon and Jimmy Darren.

On a shoestring

When Bobby was an unknown kid, the man who had faith in him, Frankie Day. used to drive from town to town introducing his boy to the disc jockeys. Between him and his future star they owned a shoestring. Certainly not the price of a motel, if they hoped to eat. So come night, they’d pull in behind a roadside billboard and sleep in the car, next morning change their suits in the men’s washroom of a gas station, and Bobby could walk in to meet a deejay looking neat as a pin. But you should see his room at home. He not only hates picking up after himself, he wishes his mother wouldn’t.

“Once Mom straightens out my clothes and records,” he moans, “nothing is where it used to be. I can’t find anything.” Can’t find, eh? Why, he and Frankie could pull into a new town and in no time flat find out which hot dog stand served the biggest wieners and the most coffee for the fewest dimes.

In those days Bobby had to do a lot of dreaming to keep going, and he still does. But the dreams have changed. He used to sit alone in his room at his drums so late at night that he barely brushed them in a soft rhythmic whisper, and dream about a girl. Sometimes it was that girl he was so shy with, the one he suddenly stopped seeing. But in his dreams she’d be sitting there all breathless and adoring, listening to him play the drums. . . . Nowadays, he doesn’t have to dream like that. Whole theater audiences packed with girls go crazy for him when they see that crooked smile and hear his booming voice. They love him, and he’s perfectly at ease with them—so long as he’s safe up there on the stage. Then he can talk a blue streak, break everybody up with laughter. It’s only when he’s caught in a crowd of sighing, crying females that he gets to feeling a little foolish over it all. Oh, he’ll stop anywhere and agreeably sign autograph after autograph till he misses out on lunch. But he still can’t dig what’s all the excitement, he’s only Bobby Rydell—a shy boy, a dreamer. Not so much girls now. Sometimes he’s Leonard Bernstein in full dress, tails and white tie, standing up on a podium conducting a huge symphony orchestra . . . other times he’s the dashing Bobby Rydell whizzing a hundred miles per hour at the wheel of a jazzy red Thunderbird.

The old dream of success used to worry his father, because he hated to see his boy all hopped up with hopes and then let down—again and again and again. But then this hard-working machinist would dig down and somehow come up with the money to give his kid drum lessons and guitar lessons and singing lessons. Now that Bobby has made it, he likes to tease his father a little. “I know, Pop, I’m a disappointment to you. When I was twelve I was playing at weddings already, and here I’m nearly nineteen and not even married.”

But the faith was there from way back. When Bobby was four, the relatives used to ask his mom, “You sure he isn’t retarded, Jennie, a four-year-old boy banging on pots and pans with a spoon? This is for two-year-olds.” Always Adrio would come in with the explanation. “To this boy it’s not pots and pans—I took him to hear Gene Krupa, and his mind’s made up. He’s going to be a great drummer.” The child was encouraged, he went around the house trying out sounds—the top of a good coffee table, the arm of an upholstered leather chair, the bathtub—whatever made a new noise. He didn’t have real drums till he saved up for them himself—in his Bishop Newman High School days. A hundred and ten dollars’ worth. And the relatives still needle his father, “After all that, did he turn out a Gene Krupa?”

So shy it hurt

The most painful six months of his school life was the time he had a king-sized crush on a girl who sat next to him in algebra. Her name was Carole Gibson—she had black hair. blue eyes and a tiny waist. Whatever math problem he did, the answer came out “Carole.” Finally, at a party, he came face to face with her. He took a deep breath and got up the courage to ask if she’d take a little walk with him. Just around the block. It was like a miracle—she would. He talked his head off—for him. First time around the block he said. “Nice night, huh?” Second time, “That sure is a pretty moon, Carole.” After the third lap, she did the talking. She said, “Bobby, are you asking me to go out with you? I’d love to.”

He’s come a long way since that night. He’s friends with stars like Annette, Joanie Sommers, Dodie Stevens, Eileen Donahue, Sherry Jackson. But he still likes to date girls who aren’t in show business. And he still gets shook-up the first time he calls any girl for a date. . . . A new phone number gives him butterflies. The kind of girl he likes is one who’ll be on time, and she doesn’t have to make one clever crack ever, just so she’s warm, sweet and herself. If a date does turn out to be a phony after all, he’ll be as considerate and nice as he always is when taking a girl out—but she’ll never hear from him again. He’ll always give a girl the choice of where to spend the evening, but he keeps hoping to himself she won’t prefer a night club. because he’s not the type. He’d rather take her to a party (Dancing to a record player in a basement rumpus room, man, that’s living!) . . . or a beach barbecue (He still loves hot dogs.) . . . or to a horror movie (She’ll get scared-and hang on to his hand.).

“Don’t muss my hair”

The list of what he doesn’t like is amazingly short: long phone calls and girls who muss his neat, oversized pompadour. (Is that the mystery about the girl he dropped so suddenly? Which was she, a phony or a pompadour-musser? He won’t say, any more than he’ll tell about the pinky ring which is practically part of him.)

He likes a million things. Swimming (won a letter at High) . . . baseball (was a crack first baseman and fast on his feet) . . . Sinatra recordings . . . Sammy Davis Jr. . . . photography . . . and many serious things. Like going to church with his folks as often as he can. He’s a Catholic with a deep faith in God. He doesn’t talk about religion much, but when he’s got a problem, he likes to get alone and pray for guidance. . . . He’s very sensitive but not touchy, and in his book, when it comes to loyalty and friendship, you can’t have one without the other. And both are fine to give and get, but not to be used as a rung on the old success-ladder.

Most important thing in the world to him are his parents. He’s an only child and has a close relationship with his pop and mom. He’ll keep little problems to himself, but talk over the big ones with them, and they know they’re lucky to have it that way. He gets to spend only seven or eight weeks a year at home, but he wouldn’t dream of having his own apartment, though he could well afford it. He loves coming home with a load of presents for his parents and the relatives. His big thrill of 1960 was the look on his mother’s face when she opened a box, pushed back layer after layer of tissue paper—then saw the mink stole!

When Bobby does come home, his folks usually haven’t seen him for maybe two or three months since the last visit. Yet they’ve hardly had him to themselves a minute when they go generous and signal the neighborhood, “Bobby’s home.” The code is via venetian blind—jiggle the slats open and shut, open and shut, over and over very fast for a few minutes. It wears out the cord, but it sure starts the phone ringing. Pretty soon aunts, uncles and cousins are crowded around the big oval dining room table and his grandmother Nina is commanding, “Eat! Eat!”

This is the family part of the homecoming. After dinner, friends will drop in, or Bobby will go out with one of his favorite home-town girls. Maybe an action-packed movie, a snack at the soda shop and some dancing to the juke box. He’s downright careful not to talk show business—he’s afraid she might get bored.

A couple of days home, and he starts in on his two perennial schemes.

“Pop, how’d you like to go along with me, invest in a nice little hide-out in Florida for you and Mom?”

“I don’t know, Bobby. we talked about it last time, remember? I’m not so sure yet.”

“Gee, but I hate cold weather. It’s nice and warm down in Florida.”

And from his mother, “And when would you ever get time to come to Florida?”

It’s true, time is one thing he has very little of. He starts in on the other project. How’s about that dog he wants to buy, the little cocker spaniel puppy?

Again his mother, “And when have you time to walk a dog? I know who’d end up walking the puppy forty-five weeks out of the year.”

This is true, too. He’s on the road more weeks than a traveling salesman. But now he’s home, and he belongs to his folks. Up in his room, he turns to the drums of his boyhood, and to his model planes. Before he knows it, he’s reaching for a wing tip and a strut. . . .

This is Bobby Rydell, a few weeks before his nineteenth birthday on April 26. Some days he makes model planes . . . and other days he talks about wanting to get married. In five years, he’s decided. Probably in the long run, he’ll end up with a neighborhood girl. Not beautiful, but cute. And his wife won’t work. She’ll give him a big family, stay home and mind the kids, cook good Italian meals, love him like crazy, laugh a lot and get one whale of a kick out of living.

Meanwhile, he’s reaching for the airplane glue. And after all, when was a teenager all-of-a-piece? A boy one minute, a man the next—sometimes even his own mother doesn’t know him.

THE END

—BY ROSE PERLBERG

Bobby sings on the Cameo label, and will be seen in Columbia’s “That Hill Girl.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1961

zoritoler imol

3 Ağustos 2023I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself? Plz reply back as I’m looking to create my own blog and would like to know wheere u got this from. thanks