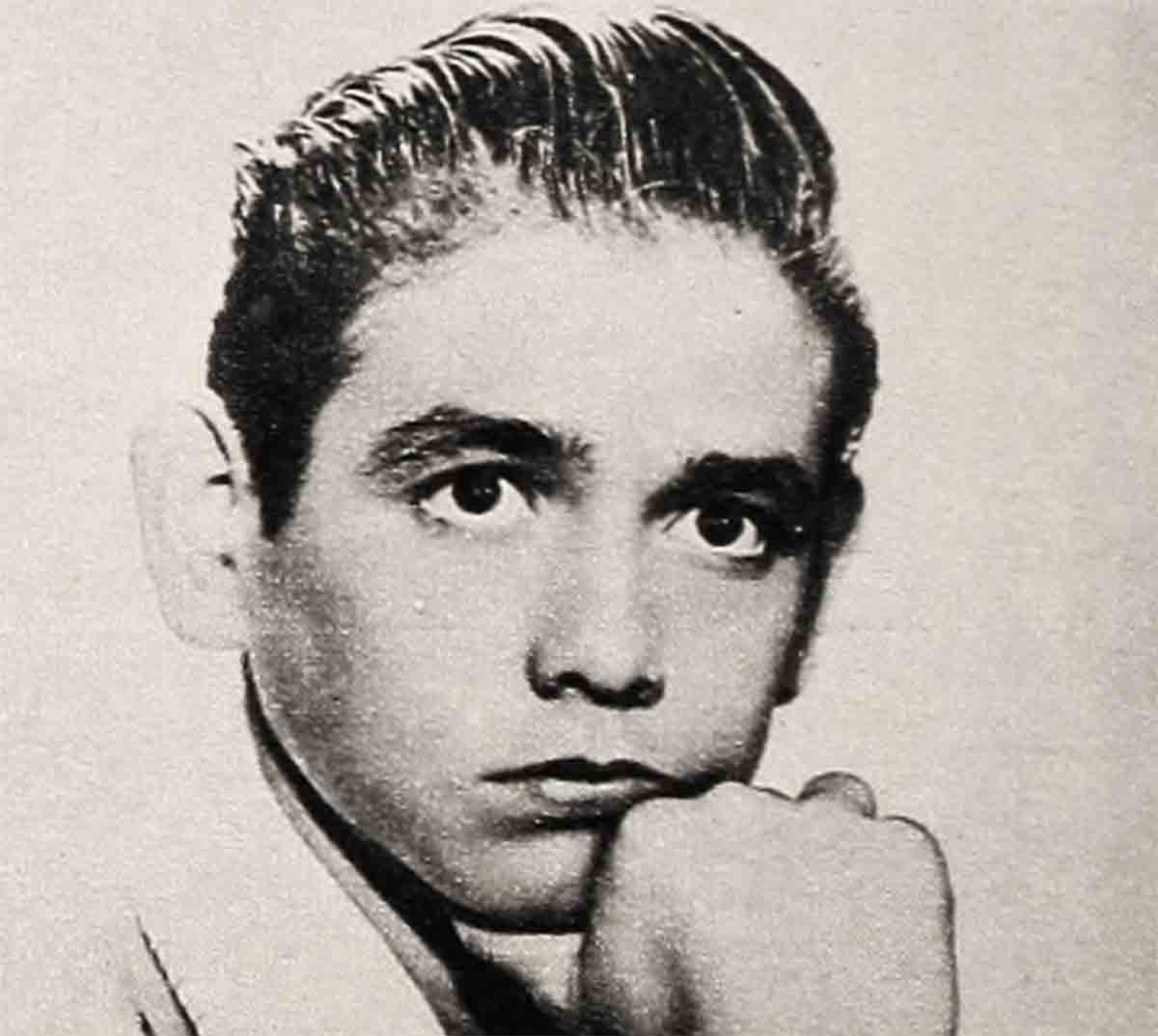

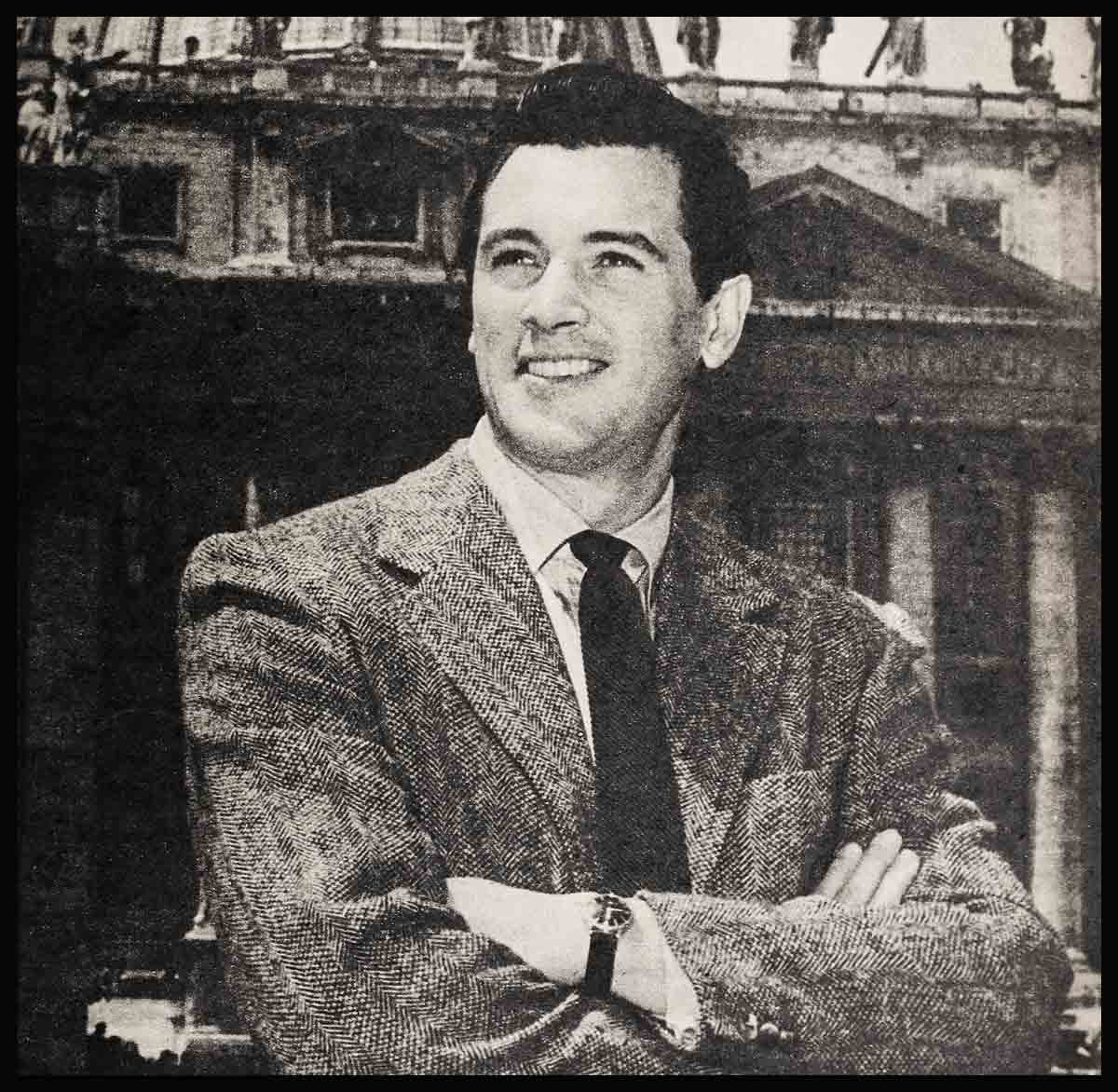

David Janssen: “I Was Too Poor To Have Dreams”

It was three years ago.

David Janssen was a bachelor then.

He was lonely. He was unhappy.

“Booze, broads and borrowing,” he once said, “and not exactly in that order—that’s the story of my young life.”

He was only twenty-seven three years ago, but he’d been around Hollywood for such a long time by then that he knew all the answers, all the inside stories, all the shenanigans and countershenanigans. And you’d have thought he was an old man had you been able not to look at him but to read his mind instead.

Nobody out-and-out accused David Janssen of being a wise-guy; at least, not to his face. But he was considered cynical, to say the least. He had few, very few, friends. He found it hard to trust people. He found it hard to get to know them. He found it hard to talk to them.

He was on his way up as far as his career was concerned. He was the star of his own TV show. He was getting five-hundred to a thousand fan letters a week. Everybody was nuts about Richard Diamond, Private Eye and the guy who played him. Producers were dickering with his agent about good fat parts in several good fat movies.

And yet, somehow, David Janssen was unhappy.

What was missing?

A wife?

He’d discount this idea pronto. What was a wife, he figured, but a woman and what was a woman but a dame? And dames, Hollywood style, with their big bosoms, their curves, their slickcombed hair, their pouting months—they moved him all right. But only so far. “In the long run they’re actresses or would-be actresses,” he once said, “—and competitive, just like men. And who needs two of those in the same apartment for any length of time?”

HE HAD NO IDEA AT THE TIME—three years ago—that there was a girl for him, a girl named Ellie, a girl he would fall for and who would fall for him and who would change his mind about the subject of marriage, and even change him.

He had no idea of her existence three years ago.

He only knew that he was.in one hell of a state.

And, sometimes, when he really pondered his fate, he would wonder how things, life, might have been for him if he weren’t an actor; if Hollywood were some faraway place the ladies in the neighborhood read about, and not the place where he lived and worked . . . and he would wonder how things, life, might have been if the trouble hadn’t started between his folks back in Naponee, Wisconsin, way back when he was just a kid of four; if his mother hadn’t been beautiful and restless and if Mr. Ziegfeld had never told her to look him up should she ever decide to enter the glorious world of show business. . . .

“And he told me I should,” he remembered her voice cry out that night, back in Naponee. Florenz Ziegfeld—she’d said. The greatest producer of them all. He’d been there in Atlantic City; there, at the Contest. He’d come up to her when the contest was over and he’d said, “I think, personally, Miss Graf, that you should have been elected Miss America. But know this,” he said, “anytime you want to come work for me, you can, Miss Graf.” . . . And that had been Florenz Ziegfeld speaking. Ziegfeld!

He remembered his mother’s voice that night.

And he remembered his father’s silence. And he remembered how it was that next morning, the morning after the trouble, standing there on the little platform of the Naponee railroad station, saying goodbye to his father, then getting on the train with his mother—just the two of them and those two big tan suitcases of theirs; how then, after a while, after they’d sat in their coach seats for a while and then had gone to have breakfast in the dining car and then had come back to their coach seats again, he had looked up at his mother and had seen that she was crying and he’d asked her, “Mama, where are we going?”

They were going to New York, he remembered her saying. Mama was going to have an interview with Mr. Ziegfeld, in his own private office. And then Mr. Z. was going to give her a part in one of his shows, like he’d said he would, and make her into what she’d always wanted to be—a star of the New York stage.

David remembered how his mother had cried, very softly and confused-like, for over an hour after she’d said that. . . .

His mother, strong and determined a woman as she was, had been very unhappy those next five years, he remembered. She had gotten to see Mr. Ziegfeld, all right. And he had given her a part in one of his productions, a big and fancy musical. Only it was a very small part and it was with one of the great impresario’s touring shows, and not his New York company.

So, he remembered, for those next five years they’d traveled around the country, the mother (she’d divorced her husband in this time) and the son and their two big tan suitcases, from city to city, town to town, living in each place for a few weeks at a stretch and then packing, boarding a train and moving on, the mother more and more heartbroken that nothing really big was happening to her, the son more and more lost in a backstage world of bright lights, brash comedians, poker-playing musicians and self-loving and cutie-pie Follies girls.

It would be, David remembers, that they would get to a hotel in a new town and he’d walk down the street during the day while everybody else was asleep, looking for somebody to play with: He’d meet some kid, the son of the owner of the cafeteria where they ate maybe, or some kid who delivered papers to the hotel. They’d become friendly. Pals. And then, before he knew it, he would have to say goodbye and he would know that he would never see this kid again, not for as long as he lived . . . He didn’t want this anymore. It hurt too much. He began to want to vomit every time he knew they were going to have to leave and he would have to say goodbye . . . So he avoided kids. He didn’t look for friends anymore. This was the beginning of a lifetime occupation for David—not looking for friends. He became a brooder. He sat alone in hotel rooms. He became a boy who just existed. It was a lousy feeling—young as he was he knew this, that it was wrong, unnatural. But time passed and there was nothing he could do about it.

FINALLY, IN 1939, when David was nine, his mother left the Ziegfeld show and moved to Hollywood. Her aim was a final fling, a long shot: to try to get into pictures. She entered the movie town with high hopes and some money she’d saved. It wasn’t long, however, before her hopes were gone, and her money; before she was working as a saleslady in the May Co. department store in order to make ends meet.

This was when she decided that her son would become an actor.

“Why?” David asked, the day she took time off from her job and started making the studio rounds with him.

“Because,” she said, “you’re a goodlooking boy and you’ve got a good speaking voice and I think you’ll make a fine actor . . . Besides,’ she added, “I don’t want you ending up a short-order cook or a car-hop, God forbid.”

(“I’ve never figured,” David says, smilingly, today, “why when my mother got excited she would pick on those two jobs. I think that deep-down she’d seen me sitting around those hotel rooms so long, doing nothing, she was really afraid I was going to wind up a plain ordinary bum!”)

Within a few days after they’d started their tour of the moving picture studios, David landed his first role. The picture was called Swamp Fire. The stars were those two Tarzans of days gone by, Johnny Weissmuller and Buster Crabbe. The experience, for David, was one of mixed emotions.

On one hand he hated the work—“the director was always goading me. And I didn’t like wearing powder and rouge.”

But, on the other hand, David had few complaints, really. Because despite what happened Mondays through Fridays, from seven to seven, he knew that come evenings, come weekends, he could hop on a bus and go to a place called Home. It wasn’t a hig place, Home: only a fourroom apartment, in fact; but for the first time in a long long time David Janssen had a room of his own and a mailbox with his and his mother’s name on it and a storage room in the cellar with a lock on it, where they parked their two big tan suitcases. And the place was far from the railroad station. And there wasn’t a cafeteria within blocks. And for the first time in a long long time young David felt something like what he knew other kids must feel like. And no, he was not complaining.

THINGS GOT EVEN BETTER after his mother re-married.

He’ll never forget the night, when he was thirteen, a couple of years after the wedding, when his mother came into his room and sat alongside him on his bed. She’d just put her new baby daughter to sleep in her crib. She was smiling. “David,” she said, out of the clear blue, it seemed, “would you like to give up picture work?”

“How do you mean?” he asked.

“Just that,” his mother said. “I’m proud of the work you’ve done, Davie. Maybe a little selfishly—but I am proud. I’ve seen a dream of mine come true,” she said. “Do you understand what I mean?”

“Sort of,” said the boy.

“And now,” his mother went on, “more important, I want you to have your own dreams . . . What are they, Davie?” She took his hand. “Your dreams?”

The boy thought for a while. Then he told them to her, gradually. He would like most of all, he said, to go to a school, a real school. He didn’t like those one-room classrooms at the studios, he said, where most of the time he was the only student in the place—just him and a teacher. And then after school, real school, he said, he would like to go to college and study something interesting, like engineering, aviation engineering or chemical engineering, something like that. He knew, he said, that college was expensive, that things were tough and he couldn’t expect his parents to pay his way. But, he said, he liked sports and maybe if he worked hard enough at them he could get an athletic scholarship to some good college, and with a scholarship, he said, well, then everything would be all wrapped up and taken care of.

When he was through, he asked his mother, “Is that an all right thing for me to want?”

“Yes,” she said.

“And you mean it,” he asked, “—about me being an actor? I don’t have to be one?”

“No,” she said. “You don’t have to be anything you don’t want to be.”

She bent to kiss him.

“Goodnight, Davie,” she said. “It’s getting late. It’s time for you to be getting some sleep.”

And he noticed, as she said that, that her smile was gone and that there were tears in her eyes.

“What’s the matter?” he asked.

She didn’t answer at first.

“Mama?” he asked. “Mama? . . . Is something the matter?”

“I ONLY DID WHAT I DID,” she said then, “because I, too, had a dream once. I’d been determined to make something of myself. When that failed, I wanted to make something of you . . . Now, I’m only sorry if I’ve hurt you in any way. I’m sorry, Davie.”

He sat up, and he put his arms around his mother.

“Don’t be sorry, Mama,” he said.

“Please, don’t be. . . .”

David entered Fairfax High in Hollywood the following week. He became, shortly, one of the best athletes the school has ever known. By the time he was in his senior year he had copped mosi of the athletic prizes being handed out, as well as scholarships to two of the best colleges in the state.

And then, less than a month before graduation, it happened—

David was in a track meet, the last one of the year. He’d just won the most impressive event of them all, the pole-vault jump. The coach had given him his medal and he was walking back towards the locker room when a newspaper photographer came rushing up to him.

“That was a sweet jump, kid,” the photographer said. “How about doing it once more so I can get a picture for my paper?”

“Sure thing,” David said.

He turned and went back to the starting line. He looked over at the photographer, who had his camera in position. “Give him a good picture now,” he said to himself. He took a deep breath, and he began to run. He ran swiftly, beautifully, surely. His eyes were on the jump point straight ahead and he didn’t see the soda bottle somebody had dropped to the ground a few minutes earlier. The pain that came to his right knee was so intense when he hit it after tripping over the bottle that he passed out. The knee was busted; the damage was to be permanent. It was as if he knew it then, that moment, even in his blacked-out state.

“My scholarship . . .” those who stood around him remember him moaning. “My scholarship.”

A few days later, he limped into his coach’s office.

“Coach,” he said, “I’ve been a little worried. Do you think the colleges will take me now, with my knee like this?”

“I’ve been worried, too, David,’ the coach admitted. “I’ve phoned both the schools. They both say that they’ll let us know the score within the week.”

But they never did.

It was then when David decided to start all over again and work at the only thing he knew—acting. He had no money. He had no preparation for anything else. He found himself, strangely, wanting to be an actor now. A good one. So he went back to all the old studios where he’d worked. Strangely, though, nobody seemed too overjoyed to see him.

Universal-International did put him on their payroll finally, however.

And the long grind began.

FOR SEVEN YEARS, minus two in the army, David toiled and struggled—“and nobody gave a damn.” Other guys came to this town of Hollywood, he knew. Some made it big. Some didn’t make it at all. But him, he just kept rolling along. He played bit parts in a couple of dozen pictures while he was at U-I. Mostly they were three and four-day deals, the kind where the director’s only concern is getting you into the picture, then getting you out.

Anyway, it was steady employment, at least. Up until 1956, that is, when the blight hit Hollywood and David got canned. He’d started at one hundred dollars a week and ended at three hundred, and this had been enough to keep him in debt. How does it happen—debt—to a guy earning a few e-notes a week? In Hollywood, what with agents’ fees, new cars, new clothes, entertaining, bachelor boozing—it happens. “Man,” David says, “it happened to me.”

So, came 1956 and he got the ax from U-I and, he figured, it was time for him to do or die in this business.

And, for a time, it looked like lilies would be in order.

First, there was the matter of a picture called Lafayette Escadrille. David’s part was that of Tab Hunter’s commanding officer. Played well, the part could easily have overshadowed Tah’s. Unfortunately for David, he played it so well that after a few days of rushes word came down from the Warner Brothers’ offices: Cut the Janssen part. Build up Hunter’s. Hunter is studio property! Bill Wellman, director of the picture, tried to fight the edict. But it was no go. Only David went.

The next incident came when Wellman was approached by David Selznick to direct his upcoming A Farewell To Arms. Fine, Wellman said—but on one condition: He didn’t want Rock Hudson for the lead, he wanted David Janssen. “David w-h-o?” quickly called off.

Finally, however, in the spring of ’57, things changed for David and he got his first real break—the lead in the Richard Diamond show. The show began as a summer replacement. But it became obvious, after the first few weeks of ratings, that it would, in quick time, become one of the top weeklies of them all.

As success stories go, it would seem right here that David Janssen was riding on Cloud Nine now, these first few months of his success.

But, to tell the truth, he wasn’t.

He was making good money now, really good money; but he’d borrowed so much all along the way, that he was still in debt.

And, though he had some stature now, some reason for happiness, he discovered suddenly that aside from his mother and his sisters, Terry and Jill, there was nobody else with whom he could share it. He had no friends.

OUTWARDLY, HE LIVED IT UP ail right. He drank with the best of them. He laughed with the funniest of them. He dated the most luscious of them.

But, basically, he had no friends.

Incidents in his childhood had made him steer away from relationships. “A cynicism of mine, he says, “—inbred maybe; I don’t know—caused me to approach someone else’s attempt at friendship from a negative point of view.” He found himself always inclined to think: “There’s a reason behind it. There’s a catch. What does he want?”

This is a Hollywood disease, easy to catch.

And you fight it, or you don’t.

And David didn’t.

And so, there he was at twenty-seven, with things going pretty well for him. And, there he was, with his problems, a lost and lonely kind of guy.

The three people really close to David—his mother and his sisters—would tell him that what he needed to solve these problems was, in simple English, a wife.

“Nuts,” David would say. “I’ve got enough to worry about.”

“I need something,” he’d say. “But I don’t need that!”

In interviews—and a whole rash of them started after the Diamond success—he would be asked the traditional question: “When you do get married, what are the qualities you would like your wife to have?” And David would answer, straightfaced, “First, she has to be willing to dye her hair every day, to disguise herself from creditors. would stop writing, and laugh. And David Janssen would have gotten out of that one.

And, yet, he knew deep in his heart that something was missing in his life.

Not a wife, of course.

. . . Or so he thought!

He met Ellie on Hallowe’en night, at a party, in 1957.

He almost never did make that party.

He’d worked hard that week, that day. He’d been invited to the party by some girl a few days earlier. But now, this night, pooped, he’d forgotten completely about the invitation and had gone to bed instead.

Shortly before ten o’clock, the girl phoned him, woke him. She was sorry, she said. She couldn’t make the party.

“Well,” David yawned, “that’s the way it goes.”

But, said the girl, she had a girlfriend who was just dying to go. Would he take her?

David said no, he’d rather not.

The girl persisted. “Please,” she said. “I promised you’d take her. She’ll be furious with me if you don’t. . . . And besides, Davie, she knows’ everybody there. And once you bring her it isn’t that you’ll have to stay with her all the time. . . .”

The girl went on and on.

Till finally David realized that sleep—the thing he wanted most that night—was out.

And so he said, “All right, all right.”

And, groggily, he started to get out of bed. . . .

Sure enough, when they got to the party, his “date” disappeared. And David walked straight to the bar and ordered a drink.

HE WAS ON HIS SECOND DRINK, or his third, when “like they say in the song lyrics, I saw her standing there, across the crowded room.”

She was tall and brown-haired and lovely-looking.

She stood alone.

She noticed David looking over at her at one point.

She smiled, and looked away.

David waited for her to look back.

She didn’t.

He found himself staring at her, waiting.

He became fidgety. (“All of a sudden,” he says, “I was clobbered by this shy, if you want to call it that, feeling. I felt she had to look back at me again to show she was interested.”)

When she made it obvious that she wasn’t going to look back (“I’d seen him sitting there looking at me,” Ellie says. “I’d liked what I’d seen. But I didn’t know what to do.”), David put down his drink, walked over to her and asked her if she’d care to dance.

She waited, those first few minutes while they danced, for him to say something.

“Well,” Ellie said, “—in case you’re interested. . . . My name is Ellie. I’m from New York. I worked as a model once, then as a buyer for a department store. I came to California a few weeks ago, liked it, gave up my job—and—” she shrugged “that’s the story of my life.”

She waited then for David to say something.

He didn’t.

Ellie began to wonder: Was this one of those silent attractions? Or was the Hollywood actor just plain bored?

They continued dancing. David continued to say nothing.

They went for a drive after the party, (David’s date, to no one’s surprise, had gone off with someone else). He said nothing.

They parked by the water. David turned on the car radio.

They stopped for a hamburger and a cup of coffee. David was silent.

“Don’t you like to talk?” Ellie asked, finally.

“Not much,” David said.

“I see,” said Ellie. She smiled. “Well, strange as it may sound, I just want you to know that I’m having a very nice time anyway. . . . Really!”

David looked at her.

There was something about this girl that made him more and more fidgety. (“She was so damn nice and normal, just to look at,” he says, “that I figured if we started saying anything to each other, the whole thing might be spoiled.”)

“What do you want to hear, anyway,” he found himself asking, then, “—the story of my life?”

“Sure,” Ellie said.

“Are you interested,’ David asked, halfsmiling, “or are you just being polite?”

“Of course I’m interested, you dope,” Ellie said. “If I weren’t, if I’d just wanted to be polite, I’d have been back at my hotel room a couple of hours ago.”

David continued looking at her.

Then he nodded.

“Well—” he said.

And he told her his story.

HE STARTED AT THE BEGINNING. And by the time he’d come to the end—a few hours later, “It was way past dawn,” he remembers—he had talked to Ellie the way he’d never talked to anyone else before. He talked about his ups, his downs. His misses, his hits. He had even begun to have inroads in discussing his problems with someone for the first time in his life—the small problems, the medium ones, the big ones.

And when he was through discussing these things, talking, he knew only two things: (one) that it was dawn and he had to get this girl back to her hotel; (two) that he wanted to, had to, see her again that night.

“I learned something about David that morning,” Ellie has said. “He didn’t ask me, ‘Is it all right if I see you tonight?’ He said, ‘I’ll see you tonight!’—like whatever shyness he’d felt at the beginning, poof, was gone.

“It was the same,” she says, “when we got married. We’d been going together for almost a year now. And all of a sudden one afternoon he comes over to see me and talks about marrying me. But he doesn’t get on his knee and say, ‘Will you etcetera etcetera, my darling?’ No. He says, ‘Either you marry me tonight or were never going to see one another again.’

“Very direct, my husband.

“Very, very direct.”

Very directly, the other day—some two years and a few months after their wedding—we asked David to tell us something about his marriage. We were sitting in the Janssen living room. Ellie was in the den, next door, working on some project. (She sews a lot, paints and is an expert furniture repair-lady.)

“Well,” said David, “it’s a good marriage. A great marriage. And it’s all Ellie’s doing. She’s got a sense of humor, which I like. She’s understanding, which I like. She makes most of her own clothes, which doesn’t hurt when a couple is trying to save money and get out of debt—which we have, finally. And she’s a good cook. Makes the best veal scallopine in town. She ieaecied from the chef at La. Scala and— Say, she’s making some tonight! You want to stay for dinner?”

Sounded fine, we said. But for now, to get back to the story—

“Has she changed you in any way these past couple of years?” we asked.

“She has,” David said. “It’s hard to say how. Ellie doesn’t do things obviously, if you know what I mean. But take the matter of friends. I never had any before, really. And I have them now. Not many. But a few. And good ones. The Jackie Coopers. The Steve Allens. A few others. How is Ellie responsible? I don’t know. People like her. They’re drawn to her. Unavoidably, maybe, they’re drawn to me, too, and me to them. I relax more around people now. I don’t question their every move. When I do Ellie ribs the heck out of me, and that takes care of that.”

He stopped, and he thought for a moment.

“And another thing,” he said then, “—she’s got me, or is getting me, out of my brooding habit. When things went wrong, professionally I mean, like with the Escadrille and Farewell To Arms things, I’d really feel lousy. I’d brood. Like I did a little while back, when I lost Butterfield 8. It looked all set. It was a big deal to play opposite Elizabeth Taylor; it was a good role, the piano player’s. Pandro Berman, the producer, said he wanted me. You can’t ask for better than that. And then word got out that Liz wanted Eddie Fisher for the role. I guess Liz hadn’t heard that I’d been set for the part; one way or another, it doesn’t matter anymore. Anyway, the opinion got to-be that the picture wouldn’t be made without Eddie. And so I was out.

“WELL, I BROODED ABOUT THIS, naturally. At least, I started to. But then Ellie had a talk with me. It was a very short talk, very simple. She said that lots of things happen for the best, que sera sera, and—knock wood—something better would come along for me.

“And, sure enough, a little while later, I landed this role in Eternity (Hell To Eternity), which I wouldn’t have been able to take if I were working on the Taylor picture. And—knock wood—if it turns out to be as good a picture as everybody who should know says it will be, well, then with this and Diamond I may really be on my way.”

We asked David to tell us a little more about Ellie, her qualities, the things about her he was most nuts about, the things about her that made her a woman among women.

“Well—” he started.

He paused.

He scratched his head and said, “You know, questions like this take time to answer.”

So he took time.

A lot of time.

Until, suddenly, from the other end of the room we heard a click. It was Ellie, opening the door that led from the den.

She poked out her head.

“David,” she said, “—is it that you can’t think of anything else nice to say about me. . . . Hmmmmm?”

Then she winked at us and closed the door again.

“My wife?” David called out.

“Why,” he said, “why, Ellie Janssen is the most sen-sa-tion-al gal who ever lived. Yessir. And I love her madly.

“Madly!”

“I hope I said that loud enough,” he whispered to us then, laughing.

“I mean, if we still want to see that scallopine tonight. . . .”

THE END

David stars in Allied Artists’ DONDI and RING OF FIRE for MGM.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1960

No Comments