Between Heaven and . . .

PART II

WHAT HAS GONE BEFORE: Anne Baxter, child of fortune, could have accepted a life of ease. Instead, at fifteen she had won her way to Hollywood; at nineteen was a star. Sensitive and intelligent amid Hollywood’s glitter, she struggled to find herself as a woman and to make her way as an actress.

The first time Anne Baxter saw John Hodiak, the man she was eventually going to marry, was at the Bel Air home of director Alfred Hitchcock.

She recognized Hodiak immediately. His face was on tens of thousands of posters and nationwide advertisements as one of the stars of Hitchcock’s “Lifeboat.” At the time he was creating the same sort of public impression that Marlon Brando was to make some ten years later. As for Anne, at nineteen she had already been in the film colony four years and had been featured or starred in a dozen top pictures.

AUDIO BOOK

But since they had never been introduced, that morning Anne Baxter and John Hodiak only nodded to each other. They might never have met if Hitchcock hadn’t entered the room at that moment and introduced them. Anne, already interested at first sight by Hodiak, could hardly restrain the excitement that was bubbling up inside her.

“Even so,” she remembers, “our conversation amounted to practically nothing. We talked, but it was just a polite exchange of the usual cliches—a sort of fence of words behind which we took occasional peeks and studied each other. As I found out later, if John didn’t know you well enough to trust you, it was like trying to touch someone shielded behind a pane of glass. There is no actual contact. And I was afraid to talk to him because I felt I was falling in love. A word or a gesture might make the wrong impression. And besides, I seemed to be falling in love with a stranger who didn’t seem interested in me at all, so that I was careful to keep to myself the truth of what was happening to me.”

That evening Anne took inventory of herself. She recalls deciding that before love a girl just is—and accepts herself without too much self scrutiny. But with love comes the great, new question: Who and what are you? She had a presentiment that Hollywood might be the wrong place to find out. It was hardly the place to inspire unselfishness, to learn how to give of yourself which is the essence of love. And this made her feel strangely sad.

“I remember asking myself why I wanted to be an actress,” Anne says, speaking of this evening. “I had thought for several years that I knew. It was the challenge, always the challenge. On the screen it is you up there. And you are asking the audience if you are justifying yourself, if you are an interesting enough person to come before them, if you have a distinctive enough identity and the talent to make it worth the audience’s while to look at you and wonder about you and possibly be won by you. Yes, a challenge that must be met—that you have to go through with.

“And I wondered. Did I love John, really, or was he, too, just a challenge? Did I want him as myself the woman, or as myself the actress? And I wondered then, as I wonder now, if this could be the story of other actresses in love, and if it might explain much of what happens to Hollywood’s romances.”

A critic has commented about Anne’s work in such pictures as “All About Eve,” “Carnival Story,” “The Ten Commandments,” and her quite new one, “Three Violent People,” by saying that she has never turned in a bad’ performance and “it appears as if she never will.”

Anne thinks this critic is wrong.

“Again and again I have felt myself horribly inadequate to a part or to a moment in a script,” she declares. “I have died any number of deaths before an audience or in front of the camera, sworn that I would never walk the fiery coals of ambition again. And, of course, that night, when I wondered about my love for John, I knew even then that my ambition might not be confined to my professional life only, that it could overflow into my personal life. And I didn’t want love on that basis. I wanted just love. But you never know. You especially never know if you are an actress, and acting is so dear to you that you don’t know where it leaves off and your own life begins.”

Events gave Anne an opportunity to find out, at least, if John could be attracted to her; soon after their first meeting they were both cast in “Sunday Dinner for a Soldier.”

For the first two weeks of the shooting he paid no attention to her at all, went directly to his dressing room after each scene, while she found herself unable to stop thinking about him. She began studying him in hope of discovering some chink in this armor of reserve he cast about himself, and found it, eventually, in his love for card games. He particularly liked to play gin rummy, and was, like most gin rummy players, inordinately proud of his ability. The only trouble, as far as Anne was concerned, was that she cared little or nothing about cards.

One noon, bumping into him “accidentally” in front of his dressing room where he had just lunched off a tray (Hodiak hated to eat in the studio commissary), she asked him if he would like to play some gin.

When he consented, after a suspicious stare, she knew she must win the first hand. If she lost that one he might not even care to play further and would probably dismiss her from his thoughts.

Hodiak dealt and her cards were poor ones. She tried to improve them but luck seemed against her or, more likely, she was inept. Then a good card came her way, another, and still another; her hand was suddenly made and she could hardly restrain her enthusiasm when she lay down her cards, shouting, “Gin.” Hodiak stared at it and then at her. Walking back to the set he was, for him, downright affable, and, she thought, was “taking her in” with his eyes rather than just seeing her.

For the rest of that day, for the first time in her career, Anne couldn’t remember one line without flubbing. And for that day it didn’t matter.

John Hodiak was bora to poverty. He was the son of a Ukrainian immigrant and factory worker in the Hamtramck section of Detroit. He knew that he faced a hard fight to lift himself to a better level of life. The theatre appealed to him early as the most favorable arena to wage this battle, and as early as his fifth grade school days he would play hookey to wangle his way into movie theatres or perhaps catch an occasional vaudeville show. When he discovered that his diction was faulty, he got a job with the Chevrolet division of General Motors, chauffeuring executives so that he might listen to their talk and manner of expressing themselves. At seventeen he won an acting prize in a Hamtramck radio station contest. At twenty-two he was a radio star in Chicago earning $750 a week.

Ali this about him, which Anne learned as they went together, won her admiration and solidified her regard for Hodiak. But she was to learn other things about him. He had an ulcer when he was still in his twenties and had developed hypertension and high blood pressure by the time he was thirty; he was much more sensitive, thinner-skinned, than he looked.

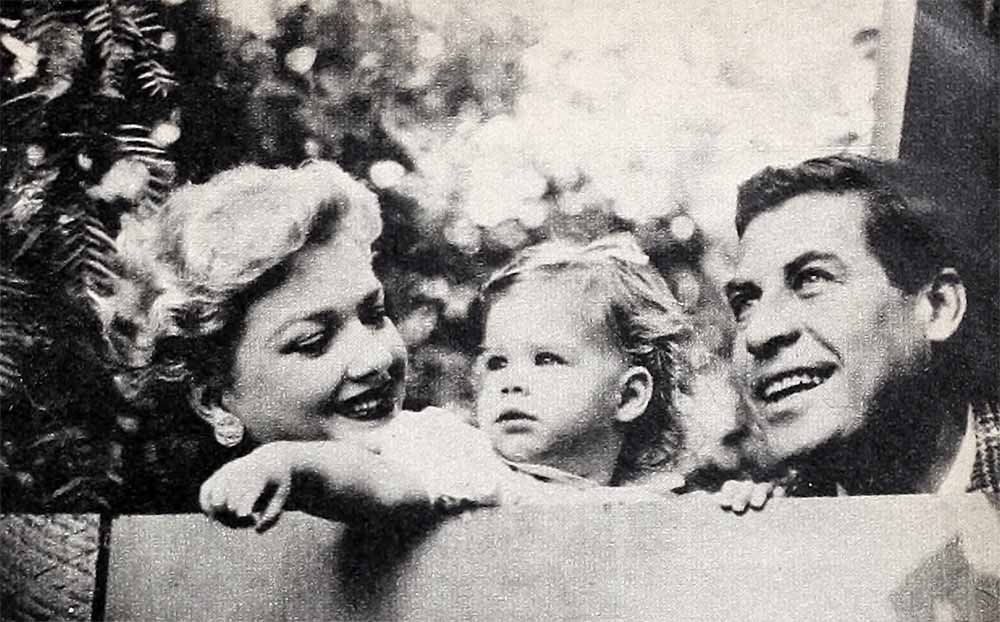

A sad story in the newspaper could move him to tears and the prospect of undergoing an emotional experience of any kind could visibly shake him. Not many people who attended his wedding to Anne, which took place in the garden of her parents’ home after they had moved to Burlingame, California, will forget the look on Hodiak’s face as he joined her in front of the preacher.

“He was so stern you thought he was about to strike his bride,” recalls one guest. Anne once arranged a surprise birthday party for him after their marriage and when he entered his home to be welcomed by a living room full of guests who had turned out in his honor his face went white and he had to retire for a while.

It was in November of 1944 that Hodiak first proposed to Anne, but it was a hesitant proposal, as if he was not sure it was a wise move for either of them, and Anne caught the mood. “Before I even answered we both knew we would not be married soon,” she once told a friend, describing the incident. “I’m sure our love was strong, but so were our fears. Perhaps we should have been braver—both of us. One of the things John was afraid about was my parents’ attitude, and he was right. They objected partly because he was an actor and therefore in a business which they thought was quite unstable, but mainly because they knew me and felt that it was unwise for me to marry a man with whom I had no common background. It was not a matter of snobbery. They liked John and came to love him. But they felt that we didn’t have strong enough mutual interests, aside from acting, to carry us over the hurdles of our quarrels when these came. And they were right. Acting didn’t help because acting, which had brought John and me together, was later, after our marriage, to hasten our split.”

Not until two years after his first proposal did Anne and John marry. Their honeymoon was a happy one. Supposedly they went to stay at the smart Broad-moor Hotel in Colorado Springs, but actually they roamed the Rockies in that region, by jeep and pony, and fell in with the spirit of the country by making a practice of staying overnight in abandoned cabins in isolated ghost towns. They would drive back to the hotel after a day or two, but just to get provisions and take off by themselves to find another lonely, but to them idyllic, retreat. Anne played one more game of gin rummy with Hodiak, lost $30, and never again pretended that she knew anything about the game. They laughed at, but slept in, horrible iron beds left behind by the miners, drank head down from rushing mountain streams and saw no other living things but birds, chipmunks, and an occasional white-tailed deer. Anne cooked and was good at making-do without proper facilities. She wasn’t so good at ironing. She tried it once with Hodiak’s trousers—the iron was too hot and he never wore them again.

The honeymoon was as happy a beginning as any two young people could have but awaiting them was Hollywood. There isn’t an actor or actress in the film colony, nor has there ever been, who isn’t emotionally involved in his or her career. There may be a few strong souls who for a while can maintain an even temperament when things are going badly—but not for long.

Events assailed Hodiak on many sides when they returned to California; enough to weight any man down. It was wartime and he tried to enlist but because of his hypertension he was turned down by every branch of the service—even the merchant marine. His last hope was to be taken in the draft. Again failure. But he didn’t look sick; on the contrary few men appeared as strong and vigorous. And this was brought out many times; by friends who didn’t know about his condition, by servicemen who would cast aspersions upon his patriotism (once a group of sailors openly challenged him for not being in uniform), and even women he didn’t know came up to berate him. Personally, he went through hell all the way and his ailment being what it was, the whole experience was doubly shattering.

There was not for him, too, the solace that might have come out of progress in his work. He was a fine actor, none better of his age at that time in the opinion of most studio heads. But somehow he missed getting the roles he wanted, and the parts he did get were indifferent ones and detracted rather than added to his stature. While this was going on, while he sat home waiting glumly for calls from the studios which began to take longer and longer to come, Anne’s name began to shine even brighter.

Her dramatic contributions to pictures like “The Razor’s Edge,” “Angel on My Shoulder” and “Blaze of Noon” were rated of major calibre. They won for her further roles in top product like “The Walls of Jericho,” “Yellow Sky” and “All About Eve.” Hodiak was happy for her; but, being both human and an actor, his happiness about her success was coupled with a sickness about his lack of it.

Anne knew what was going on. Moreover she knew that his misery was sharpened by the fact that she was doing so well. But how was she to help him—by quitting pictures?

“Life just isn’t being fair with John,” she burst out to her mother once. “He gets up at five o’clock in the morning and is miserable because he has nothing to do, and I have. A busy world is waiting for me, but not for him. It destroys a man, no matter who he is. And then, how can I come home from the studio and talk about my day when his has been so empty? Every word would be like rubbing salt in his wounds. So I don’t. So we talk about something else and we both know we are trying to cover up.”

This wasn’t all that was foreboding in the marriage of Anne Baxter and John Hodiak. Their lives had been different before they met and some of these differences began to be manifest in a way that was not only disquieting, but to Hodiak, almost devastating. His mother was a woman whose activities were confined strictly to her home. Anne’s mother, on the contrary, had many interests beyond it, social, civic, artistic, and her husband approved of them.

Unconsciously Hodiak’s idea of wife-hood was patterned after his mother and slowly this came to the forefront in his relations with Anne. He needed a girl who not only adored him, but whose universe centered around him, who had never really lived before she met him; someone who was always there when he came home at night, to whom his life was all the life she needed.

He never, during his entire married life with Anne, asked her to give up her career. But after a time it was a thing that was in the air, a sort of desperate solution, and Anne is not the first Hollywood actress-wife in such a situation to whom such a step was unthinkable.

Since life is never simple, nor even only simply complicated, there would have to be, and there was, another irritant. Because of their dissimilar backgrounds (and as predicted by her parents), Anne’s mode of life, founded on the near-wealthy scale of her upbringing, the level on which she thought and acted, her approach to people, her attitude to their combined activities, her very references, were for the most part foreign to Hodiak and often he could not hide his resentment. He sometimes took them as a reflection on his birth and childhood as the son of a factory worker.

This was the state of their marriage about the time their daughter was born. With the addition or subtraction of a factor here and there it parallels the marital state of hundreds of other film couples bygone and present. Can such a marriage endure? The record is a negative one. Few have succeeded.

“We certainly tried,” Anne has said. “We both cared about our marriage—about our love and our marriage. But maybe we were both so deeply involved as separate individuals that we couldn’t be objective. I mean that we each had so strong a personal viewpoint that we couldn’t spread it to take in and understand the other fellow’s. It’s a kind of selfishness that sets in when you think that you might be hurt making the concessions needed for a settlement. So there is no settlement—and you are really hurt.”

Anne and her husband never really talked about the things which were forcing them apart. “We talked endlessly in our heads, I think,” Anne has said, “but not openly to each other. We never had a good fight, and I think a good fight is an important device to get the truth told even if yelled or shrieked. Maybe we were both cowards, and we paid for it. If you are afraid of what is wrong you can never make things right.”

It is quite possible that even if they had faced their troubles more frankly the marriage could not have been saved. Hodiak was unhappy about his career, about the wife he had as contrasted to his lifelong conception of what a wife should be and about the lack of similarity in their outlooks generally. Anne was unhappy too, because she sensed that only by changing her whole philosophy, only by refuting the dream of acting which she had had since childhood could marital peace be achieved. And she knew she wouldn’t, probably couldn’t, change.

“What’s the use of pretense?” she confided despondently to a friend once during this period. “My whole life has been a crisis. No, not only my life, but practically everyone’s life out here in Hollywood is the same.”

There grew in her mind at this time the conviction that she was not able to look ahead ten or twenty years and visualize herself still with Hodiak and living with some degree of fulfillment. She thought of their baby and became convinced that it would hurt Katrina less if the separation came when she was still too young to feel the full impact of it. And one night when she and Hodiak were talking about themselves again, there grew in her mind the idea that things were coming to a head, that, in fact, she was trying to bring them to a head, that, as she now realizes, she was trying to make him angry enough so that she could make a final break.

She achieved her purpose by walking out of the room suddenly and going to her bedroom where she started banging dresser drawers open and shut. He came in after her and looked perplexed. “We have never done that before,” he said. “We never walked out on each other.”

She turned and came out with it. “I want a divorce!”

He studied her. “We’ve never mentioned that word before, either,” he said. Then, after a moment of silence, he turned around and left. The marriage was over.

Hodiak never seemed to show any anger about the parting (he went to live with his parents whom he had brought to Tarzana in the San Fernando Valley) until Anne filed her suit. Then for a period there was a streak of typical Hollywood retaliatory statements and actions from intervening “friends,” and they both suffered from the emotional involvements which these caused.

During the year she waited for the court decree to become final Anne sounded some confused notes in her life—a few of them rather sour. She sat some nights alternately hoping that Hodiak would phone her, and then hoping that he wouldn’t. She went blonde, hunted a new circle of friends, came out with the famous cigar bit, and figuratively played a sort of game of handball with herself as the ball and bouncing against every wall in Hollywood.

The business of smoking cigars, a habit she never acquired at all, has come to haunt her. It arose out of a misunderstanding between her and Russell Birdwell, her good friend and publicity representative. One day she sent him a note in which she mentioned a producer who, jokingly, had her take a puff of a special cigar made for women.

Birdwell decided to photograph Anne in such a smoking pose and her state of mind was such that she gave no thought to the possible consequences. A few days later the pictures were sent out to the press and one of them appeared in a New York newspaper under a caption reading, “Does she chew too?”

The impression it made was a bad one and Anne was bewildered by the minor furor it caused. Yet, actually it had a psychological explanation and represented a distracted Anne rather than the normal one. As an imminent divorcee she had not been able to shake off a sense of failure, and in this frame of mind she had trusted the judgment of others more than she trusted her own, and took a number of directions which were questionable. “Even unbelievable,” was her comment not long ago, when she was reviewing her early post-divorce days. It is hardly likely that she will ever express herself this way again.

By court decree, Anne and John Hodiak were no longer man and wife January 27, 1953, but there was still in their hearts an attachment for each other that neither could ever express, yet it would not die. When he came to visit Katrina, whose custody had been given to Anne, his manner with Anne was curt and formal. This is what she wanted, she kept telling herself, yet she would find herself at times also wishing they could be a little more friendly, a little closer—and she would find herself sometimes trying to do something about it.

One late afternoon she asked him to stay for cocktails. It could have been dinner too. But while they sat with drinks in hand and talked, they talked around themselves, rather than about themselves. “it was as if two ghosts were there,” she recalls. “Nothing that was said had real meaning, nothing could be grasped.”

A little more than two and a half years after the divorce, twenty minutes after he woke up on the morning of October 19, 1955, and called out to his mother that he was ill, John Hodiak was dead, of a heart attack. Anne, who during their married life had watched his diet and had made him go to a doctor about his condition (he had never even bothered to seek medical advice about his hypertension), suffered not only a profound sense of shock, but also one of disappointment and failure. To help him over his ailment had been one of her early hopes, taken on with the eager enthusiasm of a young wife, and then forsaken in the emotional chaos of their breakup.

His funeral in the Catholic church, in which he had once been an altar boy, was the first such service Anne had ever attended in her life. She had thought she could not even bear to come, yet neither could she stay away. His folks were not bitter, held nothing against her, she could see, when they met—for which she is still grateful to them.

“You’ll want to be alone with him,” his sister Ann said, taking it for granted.

“Oh, no—” Anne begged.

“Of course you do,” said the sister. “He looks beautiful.”

Anne made herself go then to the coffin. He did look “beautiful,” and terribly young. He was wearing a tie she had given him—and a pin, as well as his wedding ring. She found herself talking to him, saying some of the things she had always wanted to say to him—and couldn’t.

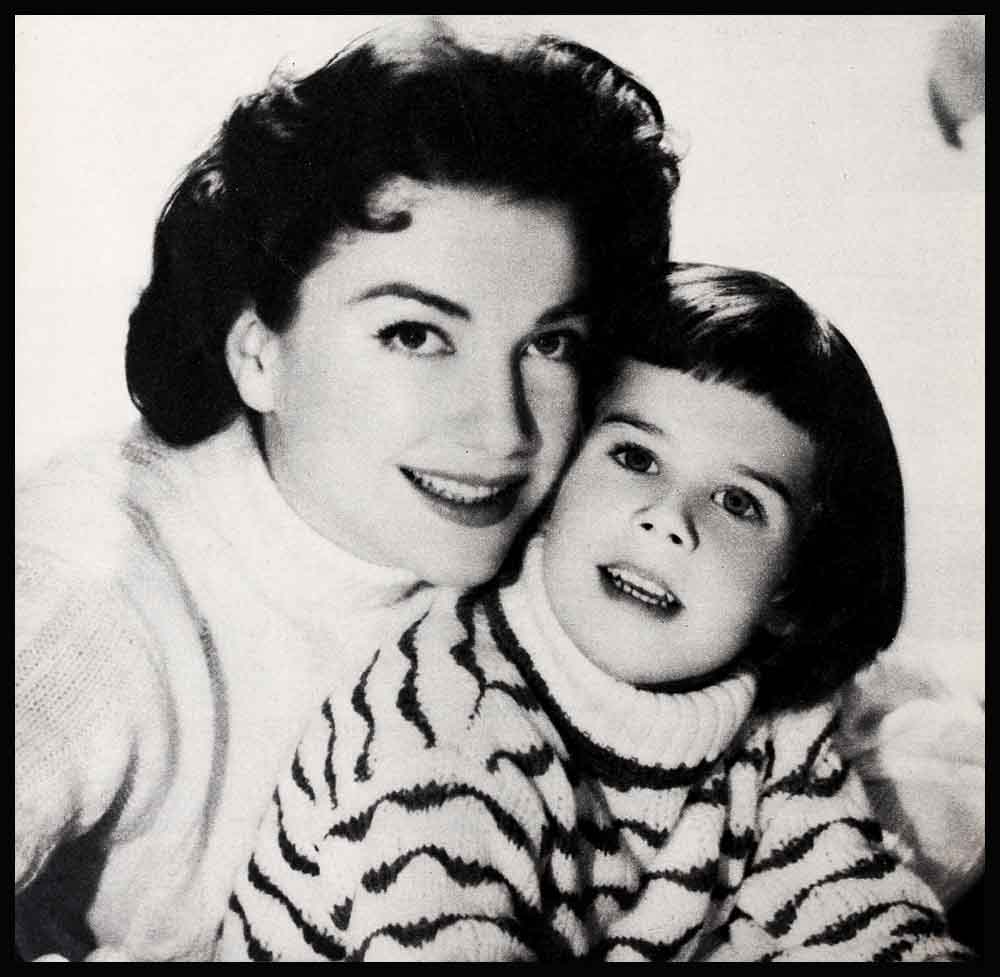

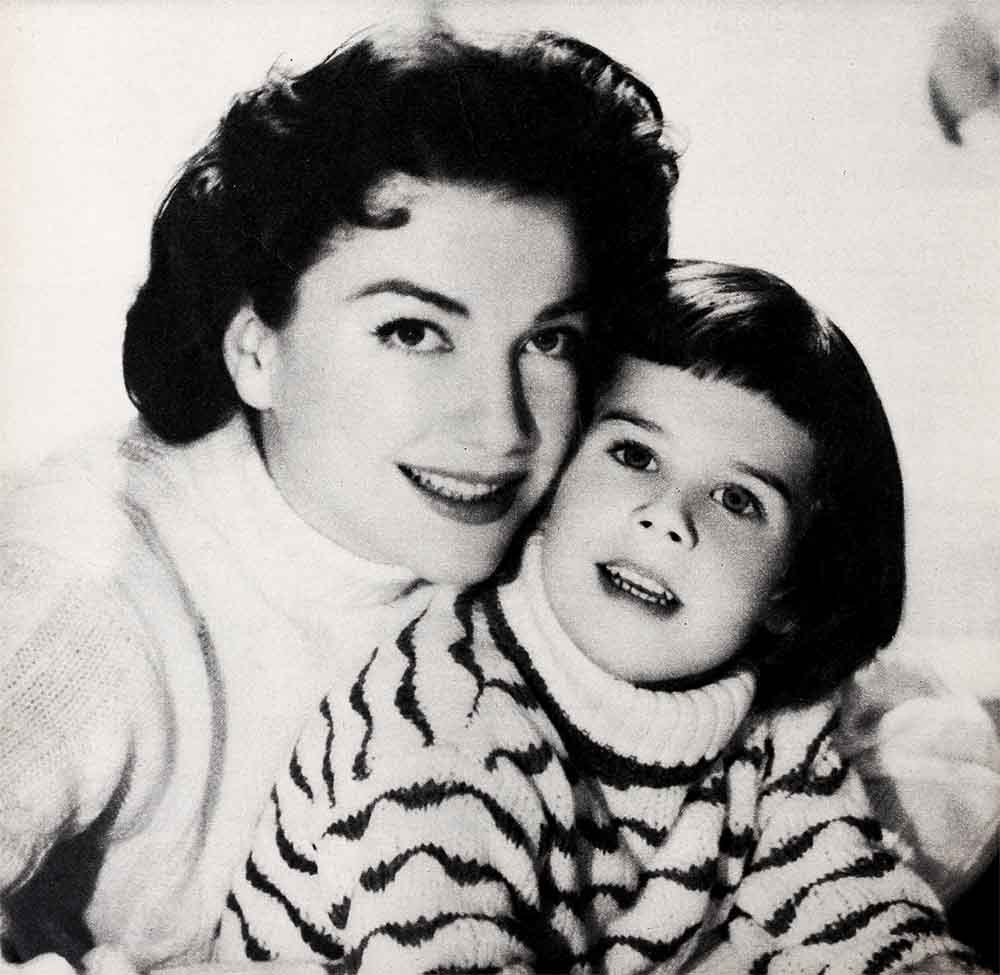

Anne Hodiak is not yet over that day, nor will she ever be. Yet she does not intend to spend her life looking backward. Through her daughter, now almost six, and through her honest desire to achieve usefulness in her profession, she is bound closely to the future.

Of her daughter, Katrina, she says, “She will love her father, even if only in memory, more easily than she will love me. She will both love and hate me. She has only the best of him. This is as it should be.”

Of her work she has a clear conception. It does not embrace any wish to be successful as a personality. It does hold a hope that she can be successful as an actress. As a consequence her preoccupation with appearance, in the Hollywood sense, has greatly lessened. She hates parts which center on the beauty of the heroine rather than her emotional motivations. Makeup men are slowly learning not to make suggestions about which side of her is more photogenic than the other, why she doesn’t have her nose fixed (she broke it as a child falling out of a sled) or how to bring out her good features.

Of her future as a woman she is, as might be expected, both clear and unclear. About marriage she is at the point where she wonders what she has to offer, rather than what she may be offered. Not long ago she was asked what she would say if a suitor proposed and she said she might reply with a quotation from “All About Eve,” as spoken by Bette Davis in that picture: “Why do you want to marry me? I’m conceited and thoughtless and messy.”

“But don’t you want to be happy?” was the question which this prompted.

“No, I don’t want to be happy,” Anne said simply and honestly. “I’ll settle to be alive and active.”

THE END

GO SEE: Anne Baxter in Paramount’s “The Ten Commandments” and “Three Violent People.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1957

AUDIO BOOK