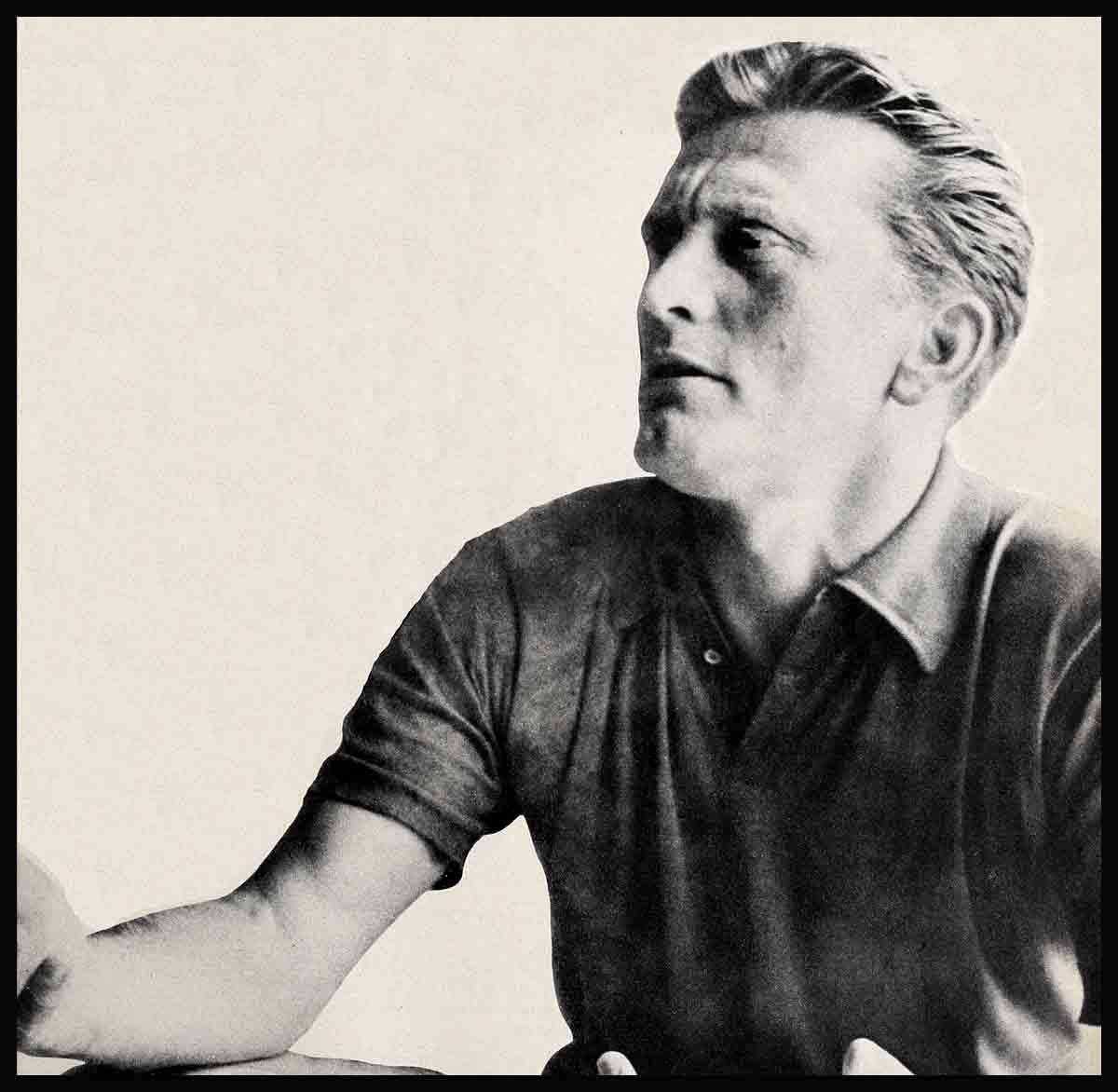

What Can Money Buy?—Kirk Douglas

“Horatio Alger,” begins the official biography of the subject of this article, “that great chronicler of the rags-to-riches yarn, would have been delighted with the story of Kirk Douglas, for it is a success story in the best American tradition.”

And, undoubtedly, he would have. But there was a flaw in the structure of Mr. Alger’s fables. He regarded attainment—reaching the top of the mountain—as the end. Attainment, however, is just as logically a beginning in itself, and this was the point which prompted Kirk Douglas to do some self-analyzing one day recently.

Money, friends, family, money, love, respect, money. Kirk has them all—but the mixture is wrong. They don’t go together at all—money and those others. There was a time when Kirk had no money. And there was a time when he had the money, the full larder, the view from the top of the mountain, physically. But, both times, he had a long way to go for the other things. He couldn’t buy them. In fact, what can money buy?

It was a fine, spanking Beverly Hills day, and Kirk sat in his fine, spanking Beverly Hills office, undisputed master of Bryna Productions, and searched his soul. He is an articulate and amusing man, who for better or worse looks not unlike Mephistopheles, but now like a well-fed and assured Mephistopheles, whereas not many years or even months ago, he was desperate, hungry and insecure.

The hunger had nothing to do with what was in his larder. As a matter of fact, there was plenty there. It had to do with what was within Kirk and screeching to be let out. It was needing to be part of the world which did, laughed, loved, gave and received. It was a hunger of non-attainment, non-fulfillment, even desperation. It can happen to established film stars. It had happened to Kirk. He was not at peace. He—

Well, put it this way: This guy had, as they say, run hungry. He’d started out from a position close to flat on his back, the seventh child of a not too well-off family, and he’d scrambled. He knew shockingly well what an unfilled larder was, and even a full one could not pacify his realization that it could be empty again. One bad picture. One boxoffice turkey. Oh, one of anything—movies and jungles are like that—and Kirk Douglas would be back as the little Demsky boy again, the one who peddled papers in the desolate dawn of Amsterdam, New York.

“I don’t know just what the beginning was,” Kirk said now. “I know the middle because this is the middle, and I think I know the end. But the beginning—all I can do is remember.

“Start with ‘Champion.’ You remember ‘Champion’?” It was Kirk’s springboard picture, the Stanley Kramer independent about the vicious fighter. “All right, after ‘Champion’ was finished, I was miserable. Absolutely miserable. I thought I’d failed. I didn’t think I’d done a job. And there were other things. My friends and advisors hadn’t wanted me to do it. I was up for the part of The Gimp in ‘Love Me or Leave Me’ at Metro. I guess I could have had it. But I didn’t think it was for me. Besides, there was this promise to Stanley. Now we’d made the picture, and I thought I’d blown everything. I was like the guy in the picture—fighting, fighting, fighting, with no knowledge of pace, fighting everything and everybody, still swinging when there was no one to fight.

“It was a crazy thing. You talk about larders. Mine could never be full enough. Over-compensation, maybe, for the hungry days. But there was no peace, no inner security. I ate five times a day, like a starving man, and that’s a psychological symptom, you know. It sure wasn’t nourishment. I kept right on looking like a guy who lived in a closet. I didn’t even know what attainment would look like—let’s not call it ‘success,’ shall we? I didn’t know that the satisfaction, the stability, has to come from inside you. I hadn’t found out that the measure of a larder is not simply how many days it would last you. I was out there on the track running without even knowing where the finish line was. I had nothing, but nothing. Then ‘Champion’—well, it did all right. That got me going. It didn’t do much more, no matter what’s been written, but it got me going. It was a point of departure.”

After “Champion,” there were many pictures. Some were good, and most were good parts. “Young Man with a Horn,” “The Glass Menagerie,” “Detective Story,” “The Bad and the Beautiful.” For Kirk Douglas the actor—fine. For Kirk Douglas the man—nothing much. Anxiety continued to nibble away at him. He fretted over never having appeared in a Broadway success (he still does). The larder could overflow onto the lawn and it wouldn’t be enough. He was alone. He was divorced from his actress-wife, Diana Dill, after some years of marriage, and today his friends think that was symptomatic. So what was wrong?

“A lot of things,” Kirk now thinks. “But the worst was, I didn’t believe in myself as an integer, a whole man. I didn’t give, and I couldn’t take. I couldn’t recognize my limitations, so I kept on fighting wildly. And I suppose I wasn’t happy being a puppet actor, with no control over parts or direction. Even when these were the best, I had this feeling of being powerless, isolated, no part of anything. I lived in a community, in a little house I’d had my lawyer buy me, but I wasn’t with the community. I had to live with Kirk Douglas but there was no Kirk Douglas. There was just this figure, who struck me as improbable, if he struck me at all. I went to night clubs. I dated around. Thank God, it seems long ago now.

“Show me a guy who dates a different girl every night and front-rows at Mocambo, and I’ll show you a guy who’s unhappy and is trying to prove something he can’t prove. But I had to find that out the hard way. Then I made the break. I cut loose. I was Kirk Douglas, independent. It could make or break me. But I had to find myself. ‘Success,’ if you have to call it that, was unimportant now. Or maybe it was important—but I didn’t have it. No salary, no fame, no number of filled larders spelled it out for me. It was somewhere within me or it was nowhere.”

Kirk stood up and stretched, revealing the flexed musculature of an intercollegiate champion wrestler.

“Now,” he continued, “I should be able to say that, at a certain point, everything changed. That’s what they say, isn’t it? But I can’t pinpoint it that way. There was the Europe bit, of course.” There had been a European phase for Kirk, which gave him a strong sense of personal and artistic freedom. “And naturally, Anne.” Kirk married Parisienne publicist Anne Buydens, whom he had met in Rome, in Las Vegas on May 29, 1954. “And a steady, warm sensation of growth and—and ease, that I’d never had. But nothing all at once. Then we came back here, and—”

Momentarily, he groped. Then he sat down and leaned forward with a kind of athletic intensity.

“Start over again with the larder bit,” he said. ‘This is for real. It’s what I’m trying to say, I think. This is what’s happened to me because I’ve found myself. Today it doesn’t make a bit of difference if the larder’s empty. It doesn’t matter what’s in it or isn’t. Because if it is empty, then I know today that Kirk Douglas can fill it again. I’m sure. That’s the peace I’ve found, or the peace that found me, or however it happened, however you want to say it. If I don’t do it acting, I can do it other ways. I can direct or I can teach, or I can go outside the industry and drive a truck. I don’t think I’m bound and constricted by doubt and egotism any more, that hopeless deal where ‘Kirk is Number One boy and nobody else exists.’

“There’s Anne and the children.” Kirk has two boys by his former marriage, and a son, Peter, by this one. “They’re Numbers One, Two, Three and Four. And we’ve built our home now in Beverly Hills. Do you realize, by gad, that I’m a citizen! I’m part of the community! I’m—I’m solid! This is everything!”

Then he reconsidered sharply, pulling himself up with a laugh.

“What am I saying?” he said. “No, it isn’t everything. But the drive now is the right kind of drive. I know when to swing and when to coast. Sometimes they ask you whether there isn’t a point of surfeit, when you’ve got it made and slap on the brakes and sit back. I’ve thought of it. I’ve thought of teaching at some ivy-festooned campus. I’d probably like it—for about a month. But why should I kid myself? When that month was over, I’d have to be back in the main stream of competition or I’d blow a gasket. But I’m not nervous about it any more. You know what I’m going to do when I leave you? I’m going across the street here and play tennis. That takes concentration. Used to be, I’d forget to change courts from worrying about what I’d just left behind. Always me, me, me. The wonderful thing is the day you find out you really live through others.”

For instance?

“Well, for instance, aside from my family, I’ve got my own company now, and when you’re making your own pictures you find you have a couple of slightly divine powers, like dispensing opportunity and happiness. And the people you help, you can see yourself through them, as you were or as you would have wished to be, and that’s a real nice feeling. There’s this girl Elsa Martinelli. We thought she’d be good in one of the pictures. I called her long distance and identified myself. She thought it was a rib. I had a hard time getting through. But when I did, she sounded very happy, and I know I was. And she turned out fine.”

Kirk made the motion of swinging a tennis racket. “You know, in this business, perspective isn’t always easy. Since being a celebrity is sometimes a by-product, you can stop seeing your own self. But I know who I am. I’m the guy who hitchhiked to college aboard the load of fertilizer. I’ve never been anyone else. Nobody knew me then. People do know me now. But only I know that it’s the same guy. The big difference is, I’ve finally found out why I did it. There was a pattern, after all. And the pattern’s all mixed in with living and giving and knowing you’re man enough to fill that larder. Not much else matters, being a celebrity least of all. That’s external and trivial, except to the extent it’s good business. Everything else comes from inside. And I thought it came from the supermarket!”

Kirk Douglas, as the fringes of history fairly well reveal now, did indeed ride a load of fertilizer to college, and did indeed have it rough in childhood. He was born of Russian parents, Harry and Bryna Demsky, in Amsterdam, a carpet and rug center, the only boy among seven children. That sounds like a likely set-up but all it got Kirk was a cup of coffee any time he had a nickel to pay for it. The Demskys were wealthy only in their new-found freedom in this country; Kirk’s working-and-school day ran approximately fourteen hours.

Amsterdam’s Wilbur Lynch High School will not remember him as much of a student, but he did achieve a rather intense brilliance in English and drama, and got to be something of an orator and de- bater. He also became dedicated to the world of the theatre.

A year of unremitting work in an Amsterdam department store got him a post-high-school grubstake of $163, with which he assaulted St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York. The assault was notably successful, although our hero had to work like a thirsty hound to get through. He wound up a grappler of high local fame, as well as president of the student body and head of the National Student Federation of America. But he was still first and last an actor. “I’ll always be one,” he said recently. “Oh, I’d like to try directing, sure, but I’ll always act. That’s what I do.”

In New York City, Kirk’s early experiences made St. Lawrence seem like a hot-bed of posh luxury. He waited table starved in a rather unrefined manner, an tried to learn his business. He did, too, but his business wasn’t in very good shape. Broadway had seen better eras and better plays, and those in which Kirk got work had a queasy habit of fainting dead away shortly after birth. There was “Spring Again,” with Grace George and C. Aubrey Smith, in which Hollywood’s beefcake-hero-to-be played a singing messenger. In “Three Sisters” with Katharine Cornell, Judith Anderson and Ruth Gordon, he was severely demoted—he was an offstage—The war intervened almost mercifully.

Kirk served well and honorably in the Navy aboard an anti-sub patrol in the Pacific, and came out a lieutenant, j.g.

Then fate perked up some. He got a nice replacement job, stepping into the juvenile lead of “Kiss and Tell,” for a departing young man named Richard Widmark. This tossed him into a promising radio career in daytime serials. But the theatre was his love, which in a way was too bad. For he performed commendably in two more far-from-commendable plays, and then in a third, titled “The Wind Is Ninety.” Whatever the demerits of this last, however, Kirk was so impressive that Hollywood—via a double play from Lauren Bacall to Hal Wallis—brought him out for a look.

There is not a great deal more to say. But what there is has to do with the fact that Kirk, a multi-linguist who plays the banjo for relaxation, lately has been pursuing the personal-appearance trail, a well-worn Hollywood route when a picture has to be sold as well as made. The experience has both exhilarated and bemused him. Within the insular boundaries of the industry itself, stars do not cause much of a ruckus. East of Western Avenue, Kirk has found it different.

“It’s an education,” he recalled. “And a pretty wonderful one. I think Ill do a treatise on it some time. The picture-goers, I mean, when they see you really walk and talk. Naturally their interest is great and you couldn’t be happier. But sometimes it’s baffling. The kids, the gee-whiz variety, them you love. As far as I can see, it’s a perfectly normal reflex, just the way I might do it or would if I hadn’t somehow got on the other side of the counter. But some of the others. One night a guy walked all the way across a restaurant to tell me he’d never seen me in a picture and never intended to.”

Kirk’s favorite admirer, however, was one he encountered during the making of “Champion.” The man was a member of the crew and an exceptionally savage one, who definitely was taking no lip from nobody, producer Kramer included. In fact, during his wild and woolly tenure, there wasn’t a soul he hadn’t insulted—with the exception of Kirk, at whom he gazed only from a distance, to Kirk’s vast relief. But finally the man approached him.

“Mr. Douglas,” he said, “you are going to be great in this picture. It’s going to make you!”

Kirk staggered briefly, then glowed. If this dean of the local critics thought it was so, then it must be so. “Thank you very much,” said Kirk, and turned to get away while his luck was running. But he was too late.

“Not at all,” said the man. “And I’ll tell you why. This fighter you play is the meanest, most vicious guy who ever lived. And you are the most thoroughgoing jerk it’s ever been my displeasure to observe. With casting like that, how can you miss?”

For years, Kirk has preserved this story. “And the guy,” he likes to say now, “could have been right, though I shudder to think of it. But it was a long time back and I was running, and I never knew about that larder. So now that I know what’s become of me, I often wonder how it is with him. Maybe he’s thriving, too. I hope so.”

THE END

—BY JOHN MAYNARD

GO SEE: Kirk Douglas in “Lust for Life”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1956