Million $ Rebel—Joanne Woodward

“See Joanne Woodward immediately,” the telegram from Photoplay had read, “she’s a million-dollar rebel who’s going to be a big star.” As far as Photoplay was concerned, there had been no crystal gazing involved; the editors just returned from a private showing of advance clips from “The Three Faces of Eve” which included a scene in which Joanne reached a pitch of near-hysteria as Jane, the girl with conflicting alter egos. For two long years 20th Century-Fox had believed in Joanne Woodward and had hung onto her contract when there was nothing for her to do except two pictures on loan-out, but when she’d made her entrance at last in a major role in an important picture, the effect was electrifying.

“Another Bette Davis,” someone in the audience said. But in meeting Joanne, the first thing one discovers is that she is too much of a rebel to be compared with anyone else. Joanne Woodward is alone and individual, she contradicts herself, confuses her friends, tells outrageously funny stories, laughs at your jokes, loves opera, despises a college sorority, longs for babies, dreams of a trip to Europe and thinks Nicky Hilton is “a rather dull young man.”

One of the most exciting and agreeably frank new movie actresses in Hollywood, she thinks people become actors because they’re searching for love and affection, admits she “dreads” marrying one man because “I’ll be so unhappy without the friendships of the other four.”

She fights with her director, but calls him “Big Daddy.” He calls her “Baby Doll.”

She can speak of shame, passion, laughter and loneliness and does so with little-girl honesty rather than boldness. She blames her career on a case of the mumps, continues to act because “applause makes me tingle,” grew interested in becoming a good actress when an older man “had faith in me” and became a professional only after “I left a good home and a wonderful father who still calls me ‘Little Girl.’ ”

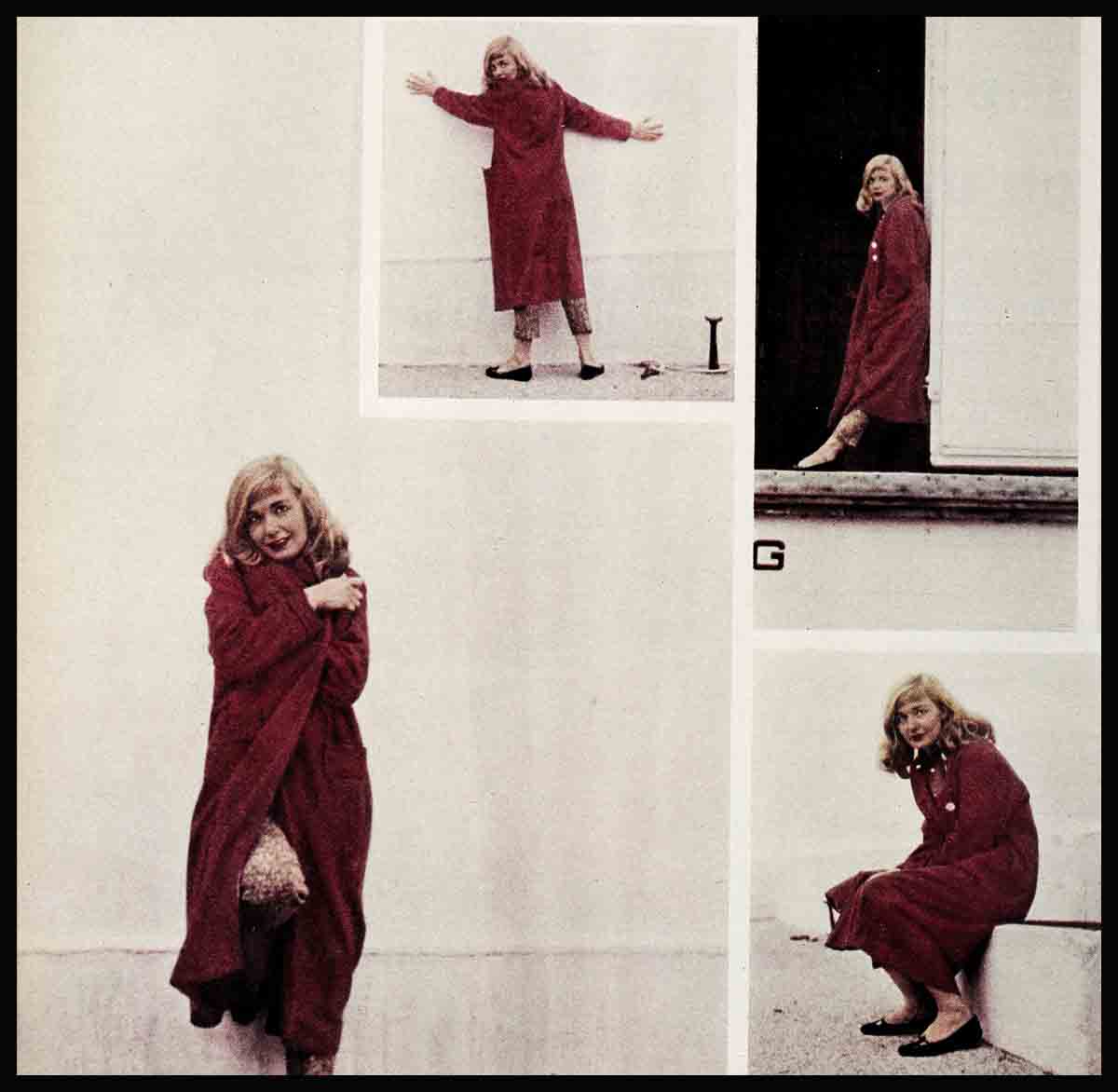

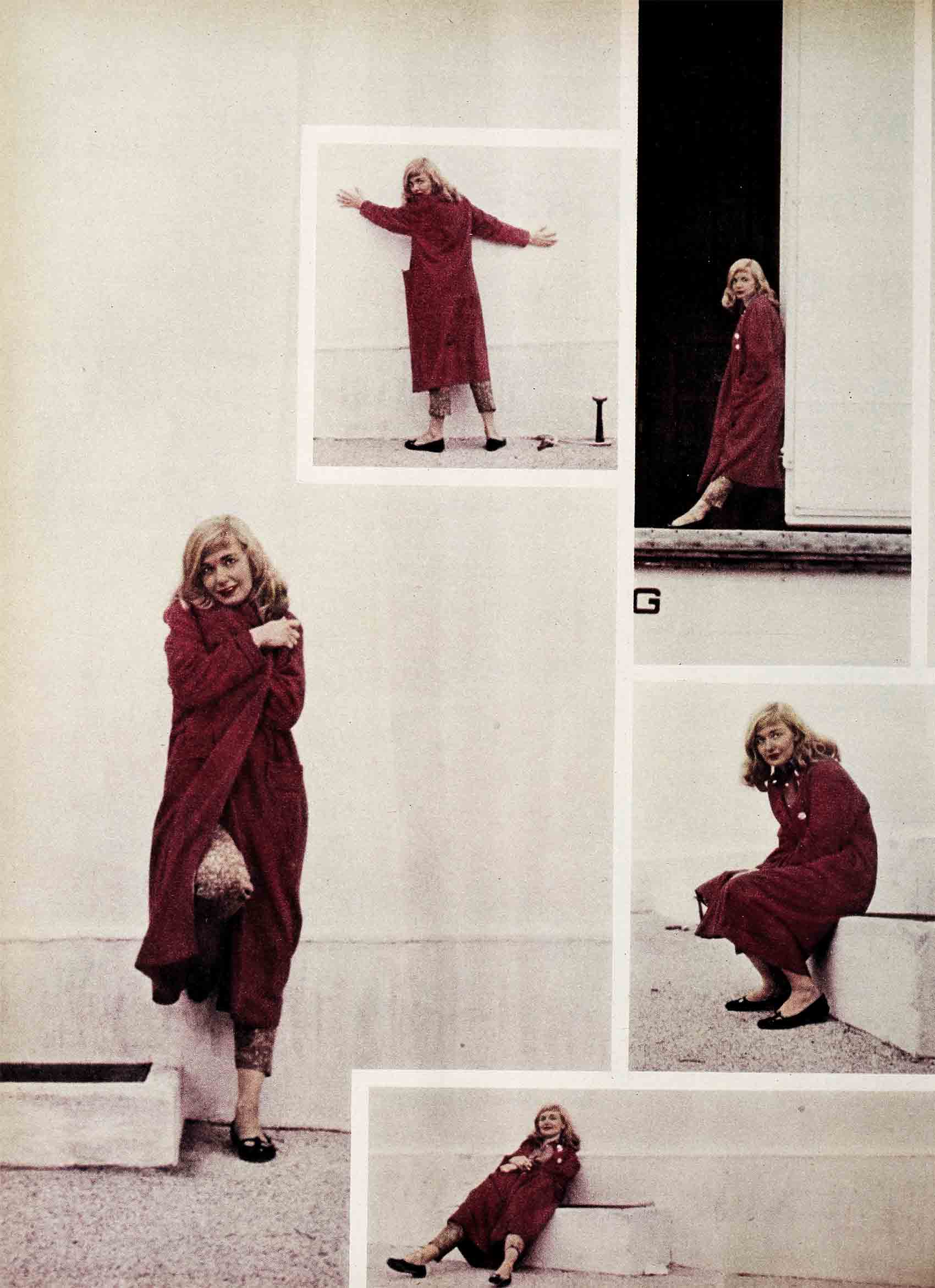

These whacky, happy, tender Woodward truths tumbled out of Joanne one sunny afternoon in Malibu recently, as she stood, sat, rolled and yogied her way through the startling story of a girl who “never had a problem I didn’t cause myself.”

Sprawled on the sofa of the small, sea-misted “apartment-house” on the shore of the Pacific, Joanne put her chin in her hands, wiggled her toes and looked out over the white-capped ocean, letting the sun fall on her eyes.

They sparkled as she remembered.

“How I love to think about the first time,” she said. “Sometimes I think it’s a lot of bunk, really; those party-dress beginnings actresses are supposed to feel started them on their careers. But like them, I love to fool myself about it. I don’t know, maybe it is true.”

Joanne thought about that for a moment.

“Let’s say some of it began when I was three, the day I stood up in front of an audience for the first time. Even then I was a substitute, somebody they had to get because the star, my brother, came down with the mumps.

“I recited ‘The Wreck of the Hesperus.’ I learned it because I always stuck close to my brother, and while mother was teaching it to him, I just listened in. Imagine, an understudy at the age of three! I guess there is something to that beginning, because on Broadway I spent three years as a perennial understudy. I was always there to loop in if the star broke a leg.

“Anyway I went on, and I can remember it as distinctly as though it were happening right now: the glorious sound of the applause. The marvelous, fantastic sensation of having everybody looking at me and nobody but me. I went through the poem again. More applause. I was starting the third time when mother came on quietly and hauled me offstage.”

Joanne bounced around into a crosslegged position, laughed and shook her head, making ripples down the long length of her beautiful blonde hair which was combed the way she wears it in “Three Faces of Eve.”

She wore a pair of snug, black velvet matadors trimmed in scrolled gold braid, a very feminine but unfrilly white blouse, no makeup except for a touch of red on her lips and the barest trace of a “doe-line” under her lower lashes.

“I’m always changing my mind, contradicting myself. I guess it did start with that. From nursery school up. I did Shakespeare at nine, the nun in ‘A Comedy of Errors.’ I liked that because it let me look sweet and sad and got the audience’s sympathy.

“Then we moved from Thomasville, Georgia, where I was born, to Mariana, and I discovered the most wonderful thing. They had a Junior Little Theatre. It was marvelous. I had found a home. We did ‘Pirates of Penzance’, ‘Little Women’—all the kid plays. In ‘Penzance’ I played the old, old pirate and had a wire coat-hanger for a hook where my hand was supposed to be. They wanted me to play the ingenue, but I scorned the whole idea. I was an actress!”

Joanne threw out her arms in a theatrical flourish that was a mixture of a rock ’n’ roll fling and Balinese exoticism.

“But in school I was a good student. I learned fast. I made A’s without effort, except in math—in mathematics I’m still stupid. I’m certain no one will believe this, but I think I studied well because I was shy. I didn’t get along at all with girls and schoolwork came easily and quickly, so the only outlet I had was doing plays. I figured that would make everybody like me and admire me.

“In the beginning that was the only purpose I had for acting. Then when I was fourteen and right in the midst of that near-hysterical phase of a girl’s life, the change to adolescence, we moved to Greenville, North Carolina.

“Men have always influenced me. Women never do. And at Greenville High School I met a man whose faith and understanding in me is something for which I’ll be forever grateful. There just aren’t words adequate enough to tell how much it meant for me to meet Mr. Albert Maclain, the head of the drama department.

“He is the one who re-introduced me to drama, to acting as being an art form rather than a silly young girl’s search for escape. I had never thought of acting in creative terms. I was just getting up on the stage and having a ball. But once Mr. Maclain explained the purpose of the stage, my whole attitude changed. He was the first to realize that I was really interested and gave me his time and his knowledge.

“So I played the leads in all the school productions, ‘Junior Miss’, ‘Abe Lincoln in Illinois,’ a lot of them. And then this grand man produced ‘Joan of Lorraine, just so I could do Joan. Oh, the way I repaid him for that favor! It’s probably the first and only time in the history of the theatre they had a Joan with long hair. But it was also time for the Spring dance and I said I’d be darned if I was going to cut, even for Joan.”

Putting her head in her hands, Joanne’s expression turned sad. “Gee, that was a mean thing to do, wasn’t it?”

“But it was a terribly tricky time in my life,” she continued. “My parents had just divorced and if it hadn’t been for Mr. Maclain and the way he generated my interest in drama, I don’t know what would have happened to me. I never had dates. I wanted them. But the boys avoided me. I liked to talk about art, books, literature, opera (I got an album when I was nine) and the boys thought I was a screwball. It made me very unhappy. And you know, in a way I was punished for not cutting my hair because of the dance.

“I was sixteen, and I decided to invite, like a silly kid, the biggest football star in the school. I think he accepted because I was tall. (That was another problem I had, towering over the other girls.) This boy was big, literally. He was six-foot-two, but it made me look good. He was the most, the richest boy, the best-looking and as I said, tall. Gosh, he was tall!

“As the dance drew nearer, my excitement was almost unbearable. For once in my life I was going to be the belle of the ball. To help things along, Mother agreed to make my gown.

“Now this was just about the time strapless evening gowns had become stylish, and nothing would do for me except that. Mom agreed again. She made the dress because we didn’t have very much money.

“And really, it was a gorgeous gown. Except for one thing. It was very loose in the bodice. Somehow, neither Mom nor I gave this particular defect the attention it deserved.

“By the time I got to the dance I realized I was going to have a very uncomfortable evening. The bodice kept slipping—down!

“The orchestra started the music and in complete, absolute girl-gushing pride, I stepped out on the floor with my kingsized hero.

“I put my arms up to reach around those shoulders.”

Joanne closed her eyes and pursed her lips and crossed her arms against herself.

She nodded slowly. “Yes, it happened. The top of the dress fell down.

“There I was. A moment ago in pride, now swallowed in shame and embarrassment, wishing the floor would swallow me.

“But the most horrible part came next. My friends—and I use the word loosely—just stood around and laughed. They roared at the tragedy of all time.

“I ran to the ladies’ room and cried for an hour. I knew I had to come out and dreaded it. From somewhere I got the courage to reappear. I walked to a corner of the dance floor and sat quietly, hoping I would die very soon.

“Then came another shock. My big, tall date had deserted me and was dancing with another girl. He wouldn’t even look at me.

“Yet this was the night I learned that men, no matter what they do, are still the most wonderful people in the world. An older boy, he was twenty-one, came over and asked me to dance. He didn’t know it, but he made the most wonderful rescue since St. George slew the dragon.

“He danced with me the rest of the night. The dress behaved: He wasn’t tall! At the end of the evening he asked me for another date and I accepted. A week later I discovered he was considered the biggest catch in town.

“Two weeks later he gave me his fraternity pin and we went steady for six months. A disaster had turned into the romantic coup of the year. It really made me in high school. I still have such a fondness for that boy, I must say. I remember him as the kind of person who could sense other people’s problems in an instant. I wonder what became of him?

“We separated because I wanted to act. It took a great deal of my time. I’ll admit that I didn’t permit anything to stand in my way. I developed a young and ambitious ruthlessness of purpose which isolated me from many of the activities most girls enjoy in high school. But I have no regrets.

“And when Mr. Maclain became head of the Greenville Little Theatre, one of the best in the South, it was wonderful. The group had its own building, everything. We did what were for me very professional plays: ‘I Remember Mama,’ ‘Years Ago,’ a lot of works by the best playwrights.

“I was graduated from school at seventeen. I wanted to go to New York to act, but Daddy wouldn’t let me. So I went to Louisiana State University instead.

“And the first thing I learned there was that Daddy had been right! He’d objected to my leaving for New York because he didn’t feel I was ready to take care of myself. I may sound like a disobedient daughter, but honestly, my father has been an endless source of encouragement, counsel and wisdom to me. Dad is very Southern. To him, I’m still a little girl. He calls me by that name and the idea that I’ve grown up is very strange to him.

“As I recall it now, I think when Dad refused me, I was grateful. I wanted desperately to go, but I was afraid. His refusal was a kind of relief. I didn’t know a soul in New York and I had never been farther North than. Washington, D.C., when I was six. I knew nothing about the North and if you’ve ever been South you know that there’s a world of difference between the people.

“So it was at L.S.U. that I realized how immature I was. But of course I immediately became involved in the school’s drama department. It was good for me and I loved it, but I longed for a social life. I was really too young for college at seventeen. I found I was entirely on my own, eight hundred miles from home. I know now I had been too well-protected.

“I couldn’t get used to the fact that for the first time in my life I was totally dependent on myself. Whether I went to class, whether I studied—all the things I could have breezed through in high school were suddenly personal responsibilities. I cut classes like crazy in the first semester, never studied, but still somehow managed to get fair grades.

“The most depressing part of that time was the sorority I got into and then found out fast that I wanted no part of it. They were the worst variety of snobs—bigoted, foolishly vain, uninspired and subject to every imaginable kind of prejudice.”

Joanne rolled over on her stomach and battered one of the cushions with her fists.

“Oh! What a bunch!

“My membership became a crisis one night when we had all the girls who wanted to join come over one evening for inspection. I saw one girl I knew. She was a gentle, sensitive person and I’d never known her to speak unkindly to anyone.

“I said to the members, ‘What about Marianne?’ At the question, they looked first at me, then at Marianne. I asked, ‘What’s the matter?’ Then one of the members said, ‘We couldn’t possibly invite her. Don’t you know her father runs a chicken ranch?’

“I stood up, walked out and never went back. I still owe them fifty dollars for dues. I’ll never pay it.

“And could you guess what those girls do now? They put out a bulletin once in a while and they include me as one of their well-known members. It’s the most hypocritical thing I’ve ever heard of. I feel sorry for all of them. What little lives they’ll lead.”

Joanne stood up and walked over to the window. Impulsively she pushed her hair from the back of her head up and over and let it fall in front of her face. “It’s wonderful to have long hair again and feel womanly.”

She came back to the sofa, sat down and continued.

“I got involved with a whole parade of boys at college. We’d go steady for a little while, they gave me their pins and we’d exchange pledges of undying love. Two weeks later we forgot each other.

“Sometimes I think that the only thing I learned in college was how to take care of drunks and stay sober myself. I got sick on liquor a couple of times and quit. And since I was usually the only sober one at a party, I learned expertly how to take care of the others. I’m only speaking of the students I knew. There were others I’m sure who educated themselves and left school as better people. But the group I got with just didn’t impress me very much.

“Maybe that’s why women don’t interest, me. The right kind of man can add so much to a woman’s life that I think we should all forget about each other and concentrate on the opposite sex.

“I guess the sweetest man in my whole life is my brother Wade. He was just the opposite of what most boys are to sisters. He never got angry with me when we were kids, never scolded me. I cannot remember him ever being unkind. And he took care of me. He let me go everywhere with him. What a wonderful brother!

“After college father still didn’t want me to go to New York. I said, ‘I’m going!’ and got a job as a secretary. If there’s a prize for the world’s worst, I claim it. I lost checks, money, misfiled the complete recorded history of one company and was an utter clerical failure. But I wanted to earn enough to get to New York.

“Then, all of a sudden, Daddy was transferred to New York City! He had been an English teacher. Now he’s a vice-president at Charles Scribner’s publishing house in charge of textbooks.

“In New York I went to drama school for two years and learned a lot. At the end of that time, I told Dad I wanted to go out on my own. He objected. I said I was going anyway. He said that, financially, I could only expect the usual allowance, sixty dollars a month. I got a cold-water flat for twenty dollars a month and lived on the rest. You can do it. For breakfast a nickel hot dog, a nickel cup of coffee. Lunch the same. Dinner, my roommate and I hoped for dates who could feed us.

“One day I heard that ‘Robert Montgomery Presents’ wanted a girl to play the young lead in ‘Penny.’ I auditioned with a hundred others.

“That script! We read and read and read and read! Finally, the choice came down to a girl named Chris White and me. When it was my turn I was tired and angry at having been kept all day. But I still wanted the part. So I threw away the script, kicked off my shoes, (I’d heard that Barbara Bel Geddes did that very successfully at auditions) and did a whole scene from memory. I got the part. From then on I’ve worked steadily on TV and in the movies.” To prove just how steadily: 20th showcases Joanne in “Down Payment” at about the same time as her Eve role.

What about Joanne’s reported intentions of marrying actor Paul Newman once he’s divorced?

Joanne shook her head. “I don’t understand why people think Paul and I are anything more than buddies. I go out with other men. Nobody mentions them as possible husbands. I certainly won’t. I have no intentions of marrying yet, anyhow. Seriously, I like my life now.

“A few days ago, on the set, I took out a cigarette. There were fifteen grips and members of the crew ready to light it for me. A few months ago I lit my own. Frankly, I like the change. I like the attention. I like the excitement. I get a lot more respect in Hollywood than I did on Broadway, but the stage is where I really want to be successful.

“And I don’t think I’m ready for marriage. In the first place, I can’t take criticism as well as I should. It used to throw me into a panic. It doesn’t any more, but it still makes me unhappy. That attitude wouldn’t be good in a marriage.”

She threw her hands back and let them hang limp behind the sofa.

“Oh, why does a girl have to marry? I know I’m going to marry someday, but right now there are five men I like. If I marry one, I’ll be so unhappy without the other four!”

Hollywood may fascinate Joanne. But right now this girl, though she doesn’t know it, is fascinating Hollywood.

We had been talking for nearly three hours. The sun was already down and a slight wind had come up. It would be dark soon.

“Night’s coming,” Joanne said. “That’s a nice time for me. There’s something peaceful about evening. And you can think about tomorrow. I wonder what will happen to me tomorrow?”

We didn’t answer. Who can tell?

THE END

—BY LOU LARKIN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1957

No Comments