Is June Allyson Retiring?

June Allyson has sometimes been called “Allyson Wonderland.” The term is applicable if used in reverse. Hollywood has been but little of wonderland to Allyson. She has not found stardom and greatness synonymous.

Perhaps there was a time when June found films a challenge. She proved to herself that Hollywood could be taken, and she took it. A couple of years ago fans voted her their number one choice among feminine stars; the following year, their second.

Though appreciative of the honor, June was not obviously impressed. Another star recently said to her, “It’s amazing that you can be so popular with all the bad pictures you make.” June didn’t know whether it was a slam or a compliment. “I never got around to asking exactly what she meant,” said June.

June went into show business for two reasons. She had to make a living; and she wanted to convince friends, who had dared her to try, that she could make a go of it. She has a childlike quality of acceptance. Her click in movies neither amazed nor exhilarated her. When she wished to learn to dance, she went to see Fred Astaire in “The Gay Divorcee” seventeen times, studied his technique, and landed herself in a series of Broadway musicals that eventually brought her to Hollywood.

It seems that everyone wants her to be a movie star but June herself. Making motion pictures is to her a job, like selling ribbons over a counter, and she does it well. Two years ago Dick Powell said to me, “June’s the best actress I know. But she’s the most un-actressy actress you’ll find in Hollywood. I honestly think that on a lot of mornings she wouldn’t go to work if I didn’t urge her. It’s not that I care whether she works or not; but I do believe she’ll regret passing up the opportunity later on.”

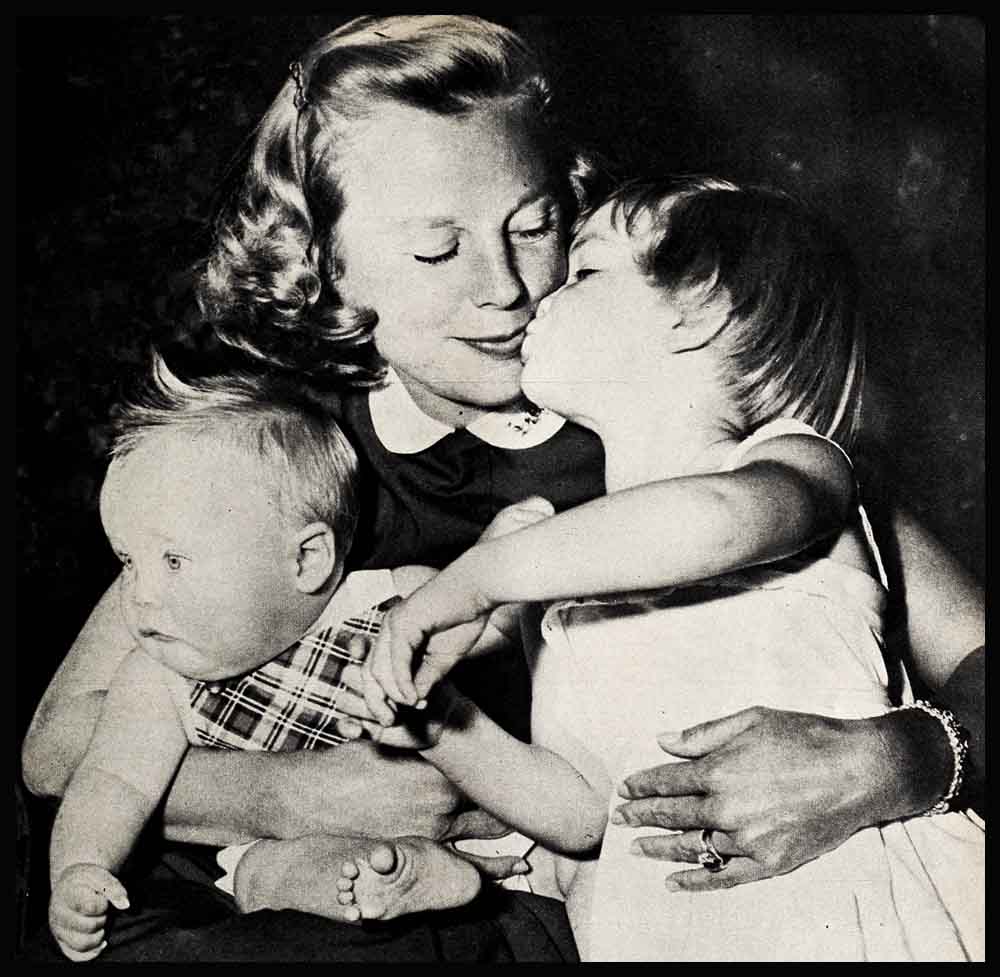

At that time June had an adopted child and was expecting another of her own. She seemed to look at us in amused wonderment as we talked about her career. ‘Tm not a career woman,” she explained. “I don’t like to fight, and in this business to get what you want you have to fight. I’d just as soon stay home and raise babies. I’ve been the happiest since the time I learned the stork was headed my way. For the first time in my life I feel important. I’d like to have at least five babies. But Richard (that’s what she calls Dick) thinks he’s a bit too old for such a big family.”

I pointed out that a girl could have children and a screen career too, citing Esther Williams, Jeanne Crain, and Lana Turner as examples.

“I still don’t like to fight,” June repeated. “That’s Richard’s department.”

Her attitude hasn’t changed. Recently she told me she wanted to retire and devote her entire time to her family. Like many mothers, she shed tears when she sent in a school application for her daughter Pamela. “They grow up so fast,” she said. “And even when working in Hollywood I miss being with my children.”

Here indeed was a Hollywood phenomenon: a top star who didn’t care about being a star. When I asked if she went to the studio while not working, she cast those innocent eyes upon me as if I’d wanted to know if she wished a trip to the moon and said, “What for? I’ve got everything I love at home.”

June’s contract with M-G-M ends within a year. I called Dore Schary, head of production at the studio, and asked him what he would think if June retired at the expiration of her contract. He hardly waited for me to get the words out of my mouth before replying, “She won’t retire.”

“What are the qualities that make her such a big box office star?” I asked.

“She has a fresh personality, an honest kind of personality,” he replied. “She lends validity to a role. She reminds me of something in a picture we just produced about Hollywood, ‘The Bad and the Beautiful.’ In it Kirk Douglas says to Lana Turner, ‘I know you’re a star, because when you’re on the screen no matter what you’re doing or who else is in the scene the people in the audiences are looking at you.’ That’s true of Junie.”

“What are her strong points as an actress?” I asked.

“Any good actress must have understanding of other people’s problems, and June has,” he said. “She also has that curious quality called talent—the ability to project herself and make others believe what she does. You know when you turn out the lights in a big room and start showing pictures, the good actress makes you think, ‘This is really happening.’ She can make one scared, happy, or sad. June has this ability to make others think make-believe is real. This is what we call talent.”

“Do you think she’d actually be happy in retirement?” I asked.

“Oh, no,” he quickly responded. “She’s much too young to retire. Any personality as vibrant as she would be unhappy doing nothing. It would get tiresome. You know we all say that in a couple of years we’re going to retire, but somehow it seems that we never do.”

This is the opinion of the man who’s June’s current boss; and the person who will likely get her signature on a new contract, if she puts one anywhere.

To get another answer, I went to see the popular young miss in her Bel Air home. She and Dick had just finished dinner before an open fire. June, wearing quilted lounging pajamas and red felt slippers, looked hardly more than a child herself. She had on horn-rimmed glasses, but removed them when she started talking. A mannerism she has of hugging her knees in her arms added to her juvenile appearance.

Our conversation started with politics; and June began telling a story about Dick. He interrupted her with, “You’d better let me do the talking, because I’ll get the facts straight.” June stuck out her tongue at him and went right on with the story. On finishing, she asked, “Now, wasn’t that the way it was?”

“Yes,” he admitted. “But you never give prefaces.”

“Oh, I don’t have to go on and on to tell a story,” said June.

Dick looked at her in a patient sort of way, continued his discussion of politics, and stated that he was not a rabid Republican.

“Thank God, you’re not a rabid anything,” chimed in June, whose every look and gesture indicated she was head over heels in love with the man. As she sat there with her chin on her knees, one couldn’t possibly conceive of her being among the most popular film stars on earth, with the question of her quitting pictures causing many a producer and exhibitor to tremble in his boots.

It was plainly obvious that Dick was lord and master of the house, and when June had the opportunity to toss him a compliment or turn the conversation over to him she never failed to do so.

“In his new picture, Richard co-starred with Lana Turner,” said June. Then as if suddenly recalling the event, she looked around with a very wise, impish expression on her face, and exclaimed, “Lana Turner! I was on that set every day Richard worked.”

She glanced about the room, feeling something was wrong. Finally she got up and replaced a chair. “My daughter’s shifted its position,” she explained. “She’s a furniture mover.” It was typical of June to veer from Lana Turner to an action of her child. Unlike most Hollywood stars, she appears bored with talking about movies. That’s one reason I believe she actually would like to retire.

“I want to direct,” said Dick, who’s very much a business man. “As an actor, I’m tired of holding in my stomach.”

“Rich-chard!” remonstrated June.

“You’re doing all right,” I said to Dick. “Who’s your manager?”

“Me! Allyson,” said June.

“Okay,” I said. “Now comes the $64 question. Why do you want to retire from pictures?”

A helpless expression came over June’s face. With a wide, sweeping gesture, she turned the question over to Dick.

“You answer it,” he said. “You made the statement.”

June settled back into a lounge as if accepting the inevitable. “It’s really very simple,” she said. “I love my career, and I’ve been very fortunate in movies. But I don’t see why I should waste time doing something not worthwhile. The studio sends me a script. I read it and say, ‘I don’t want to make the picture.’ The studio insists that I should. So I do. Then I’m told by studio officials that the picture wasn’t very good. I knew that before I started working on it. Actually I want to retire from bad pictures. People don’t want to see run-of-the-mill films. Take somebody making fifty dollars a week.”

“Who do you know who makes fifty dollars a week?” Dick interrupted.

“My father,” said June.

“He does better than that,” said Dick.

“You’re thinking of my step-father,” June corrected. “If my father wants to take his wife and three children to a movie, he has to spend seven dollars. He doesn’t have that much money to spend. He can’t afford it. That’s the reason I don’t want to waste either the studio’s or my time by making mediocre pictures. I’m married and have two children. I’d rather spend the time with my family.”

“Are you getting lazy?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “But my children need me. When little Pammy falls down and cuts her leg, the nurse tries to help her. But Pammy won’t let her. She says, ‘Oh, no, mummy will come downstairs and fix it.’ So I go downstairs and fix it, and everything’s all right. When I go to work that little thing is always in the driveway to see me off.” Mimicking the little girl’s voice, she continued, “Pammy says, ‘Will you be home before I go to bed, Mummy?’ That’s not easy to take. I want to spend time with my children.

“But, as I said, I’m not a fighter. When anybody pats me on the head and asks me to do something, I’ll do it. If I go into a store, and a clerk shows me something, I’ll buy it. I don’t want anybody to be unhappy. But most of all, I don’t wish to be unhappy when I’m working. It makes me nervous. So I bring the state of mind home with me. I get mad at Dick and the kids. I grumble a lot, and that’s not right. I can’t blame the studio. If M-G-M had a good script suitable for me, I’d get it.

I’ve had about everything a film actress could expect except an Oscar; but don’t get me wrong. I have no burning desire to own one. However, if I were ever nominated for an Academy Award, I’d be down sweeping out the theater so it would be clean for the ceremonies. And I’m not saying to M-G-M, ‘Give me a good picture, or I quit!’ That would be childish. For my birthday two years ago, the studio gave me an $18,000 dressing room. The boys said, ‘You’ve been a good girl, so here’s a present.’

“Although I’ve turned down scripts, I’ve never been suspended. A classic example is ‘The Stratton Story.’ When I read the script, I saw there was very little in it for the girl, so I said I wouldn’t do it. M-G-M told me I wouldn’t be suspended for refusing to make the film but I was still wanted for it. Then I put up the argument that studio officials—not me—claimed I was one of their biggest stars and asked why they didn’t protect their property. ‘Well and good,’ they said, ‘but we want you for the picture,’ So naturally I gave in. Then I went to Sam Wood, who was to direct the film, and explained that doing the picture was no wish of mine and that I’d have to depend upon him.

“My part in that film was strictly Sam Wood. He and Jimmy Stewart would come to my dressing room after working hours and cook up whole scenes for me. Jimmy would say, ‘June’s my wife. She’s he big star. Moviegoers won’t want to look at me; they want to look at her.’ So we rebuilt the whole picture around that idea. Now it’s my favorite film.

“I’ve repeatedly told June that as long as I can walk and breathe, there’s no necessity for her making a picture she doesn’t like,” said Dick. “But she’s an actress; and not a hausfrau. And to an actress there’s nothing more gratifying than doing a job well. June wouldn’t be happy in retirement, because she’s got acting in her blood. An actress simply hasn’t the quality in her make-up to be indifferent to seeing herself fade from the public scene. If June had a substitute, got busy doing something else, I would think retirement would be okay for her.”

“Busy!” exclaimed June. “I’m busy doing things that I want to do—not things you want me to do. I want to stay home.”

“How do you spend your day?” I asked.

“I get up at eight o clock in the morning,” said she. “Then I go in to see the children and straighten out all their difficulties. I’m on a committee for the Good Samaritan Hospital. We arrange to send flowers and reading material to the patients. I‘m also in alt the charity drives for St. John’s Hospital. I believe in working for my community. After all, my children are growing up here. Now I’m selling tickets for the Hollywood Bowl. Want to buy one?”

“Buy one?” I asked. “I’m selling them myself.”

“Then we’d better get off that subject,” said Dick. “But I do get sick of hearing actors talk about how nerve-wracking their business is; and how they hate it. Sid Luft gave the best answer to that I’ve ever heard. We were dining with him, the Edgar Bergens, and Judy Garland in San Francisco, when the girls began to complain about the hardships of show business. Sid said, ‘Well, you’re either equipped for it or you’re not. If you Ye not equipped, you should get out.’ ”

“I don’t mean that I’m neurotic,” said June. “I just can’t relax when I work. I love the film industry, and 1 think it’s been very kind to me. But Richard and the children are the most important things in my life. I want to continue in pictures if I find the work interesting, enjoyable, and rewarding—but not for the simple sake of being a movie star. So far I’ve never learned to lake it easy while making a picture. I never go into my dressing room to read or write letters, for instance. I work from the time I enter a sound stage until I leave.”

“If you should retire, what would you do?” I asked. “You couldn’t spend all of your time on charity committees.”

“I’d have another baby right away,” she said. Then she looked at me with sudden astonishment at the question. “What would I do!” she exclaimed. “Did you ever run a house and take care of two kids? We have a nurse, a butler, a cook, a gardener, and two secretaries. But they all have to be directed. I take charge of the children myself. Having a nurse is wonderful; but children also need the help of a mother. I teach Pammy to read, write, and draw. Then we go to the beach and on hikes. Passing on to them what little knowledge I have and seeing them discover new things for themselves is really thrilling. That’s why I insist on quitting pictures before I get too old for them. If I find good stories, I wouldn’t mind doing one film a year.”

Dick laughed. “She’ll re-sign with M-G-M. June, despite all she says to the contrary, is primarily an actress. And she won’t find any satisfactory substitute for acting.”

“I’ll buy that,” said I. “Her friends are non-professionals; and every one of them would give his right arm to have what June’s got. They work hard to keep busy, and what do they do?”

“Talk,” said Dick. “Talk.”

June smiled. “I guess this guy is what the doctor ordered. When I was sent the script of ‘Battle Circus,’ I said, ‘I won’t read it.’ We had planned to go to Europe, and I didn’t want to do another picture. ‘You can at least read the script,’ Dick argued, ‘and then you can tell Metro why you won’t make the picture.’ I said, ‘I will not. Why should I?’ His answer was: ‘Either you work or you don’t work. You can’t do things half-way. Read that script, June.’

“I was watching television, but I got so mad at his insistence that I turned off the set and started reading. He just sat there and watched me. When I’d finished the script, I said, I’m ashamed that I didn’t have the intelligence to read it so I could give the studio my opinion cf it.’ We discussed the picture, and I said, ‘I want to do this film, Richard; but it means we can’t go to Europe. But I’d rather stay home anyhow.’

“ ‘So would I,’ roared Richard. ‘And you know what? I was beginning to feel too old to play in a film with you. But now that you’re going to co-star with Humphrey Bogart, I’ve changed my mind!’ ”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1952