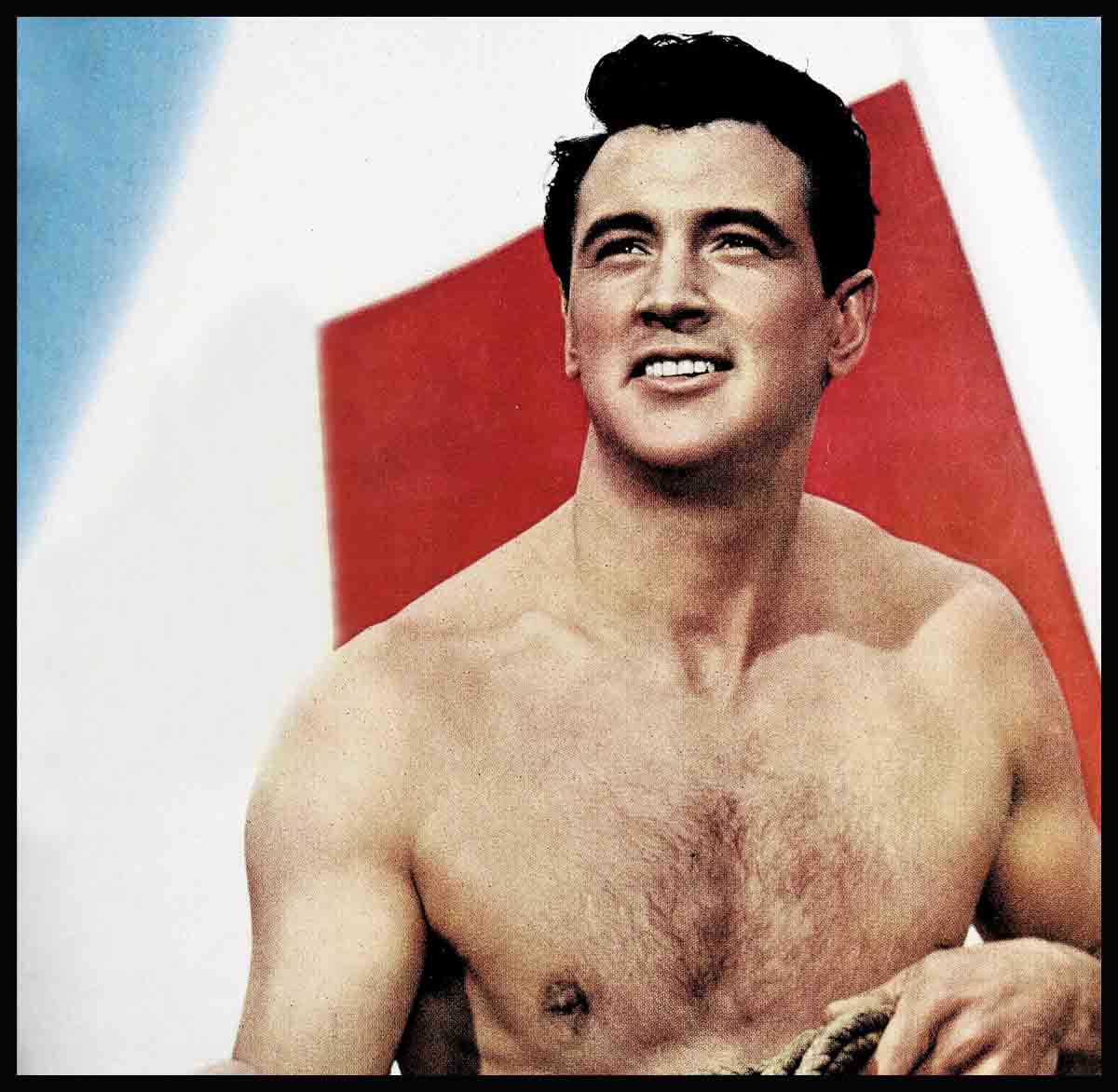

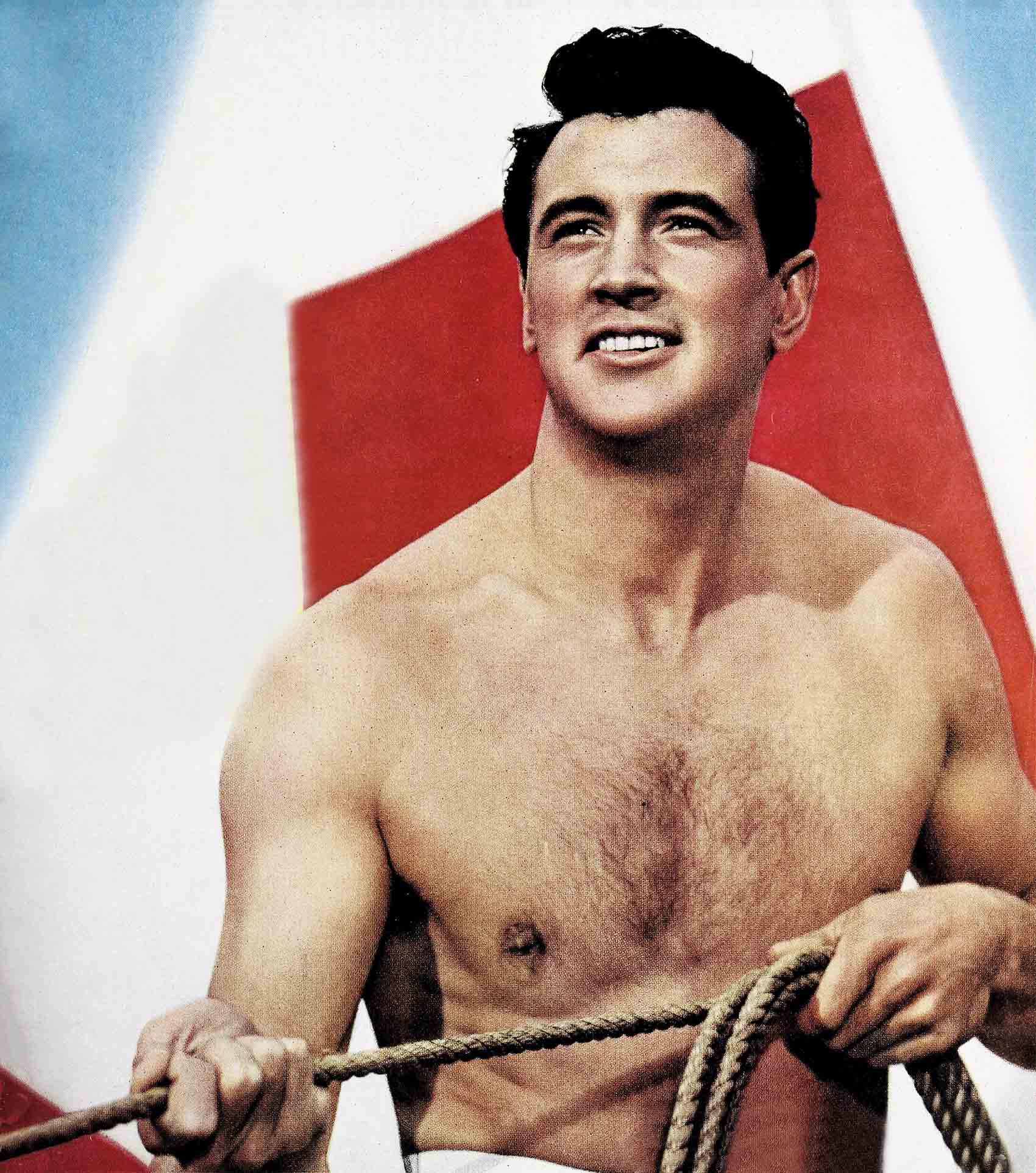

Rock Hudson’s Magnificent Obsession

This is your magnificent year.

The whole movie-going world hails your deep and moving performance in a spiritual message for which you were long ago prepared. . . .

Your triumphant hour is born of a small boy’s heartache and a mother’s prayers and mellowed with the wisdom of a farm woman whose roots are as deep as the land she early taught you to love.

“We plant the seed—so . . .” she said to the small boy scuffing along the furrows of an Illinois farm. It would take both the sun and the rain to make it grow. But the seed would grow—because the soil was good. And some day the land would give it all back threefold. “We work hard—and the harvest will come. . . .”

Yes, from your German-Swiss grandmother you get faith and assurance that no matter how dark the night—the dawn finally will come and the harvest will be here.

You will need this faith—and your mother’s prayers—to chart your course through the dark rainy days to come, to guide you through years of discouragement, illness, accidents and poverty. Through your years, Rock Hudson—This Is Your Life. . . .

Turn with us as we turn back the pages in the book of time to the beginning of this boy, whose dreams and ambition—flanked by faith—have carried him right to the top in his chosen career.

It’s November 17, 1925. A son is born to a garageman in Winnetka, Illinois, and his pretty wife, Kay. You weigh 5½ pounds and you’re 27 inches long—so thin the nurse wraps your shirt around you to keep it on. But you’re a big noise even now—according to that nurse, Pearl Scherer, today Superintendent of Nurses at Deaconese Hospital, St. Louis, Missouri—and your own Aunt Pearl.

“Yes, he was, Ralph. I was right there, and I’ve loved him like my own son ever since. His leg was broken in an accident when he was six months old, but Roy was the best-natured baby through it all. My nephew deserves everything good that has come to him. He’s always been a good boy and a hard worker. And I’m not surprised at the name he’s made. From the way Roy squalled the night he was born, I knew then he’d make himself heard as he went through life.”

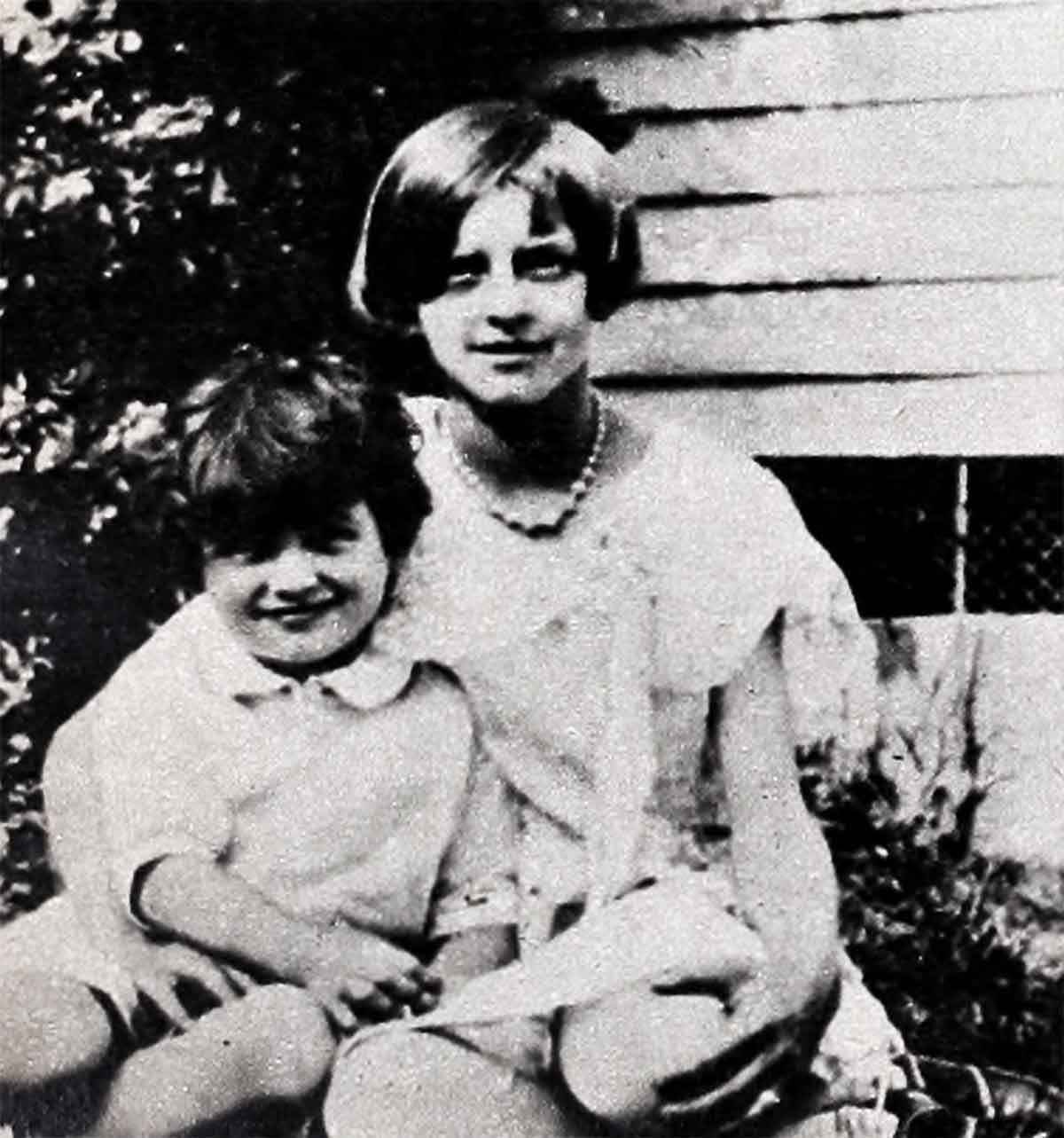

Your Aunt Pearl had you pegged right from the start. And we’re going through the early years of your life right now, to 1929 and a four-year-old who’s devoted to a dog named “Crystal.” You have the widest grin and the most engaging Buster-Brown bob in town, and the relatives shed a tear when your hair is cut this year.

It’s 1931. You’re six years old—a very sensitive six—and you’re deeply hurt when your parents separate. Your mother, heavy-hearted, can’t tell you why. She goes to work, determined to be both mother and father to you.

The years between seven and ten are tough, hard years for you, Roy Fitzgerald. Your mother works as a waitress, a baby-sitter, at whatever other work she can find. You take a paper route and you’re paid seventy-five cents a week at a neighborhood grocery store after school, carrying packages out to cars for customers. But there comes a day when your mother’s out of work, when there are no more pennies in the cookie jar and no food in the cupboard. A day your mother, Mrs. Joseph Olsen, now happily married and living in Arcadia, California, will never forget.

“We lived for a whole week on potatoes and bread, Ralph. But the hardest part for me during times like this was not having a dime to give Roy for the weekly movie at the Community Theatre, where all the other youngsters went on Friday nights. I didn’t tell my family how tough things were for us, but one day Roy’s Uncle Jim came by around meal time. ‘Is this all you have to eat?’ he demanded. Without another word, he went to the store and came back with a basket overflowing with everything, including candy for Roy. This was a real celebration.”

But there are fun days through childhood too, Roy, when you visit the farm of your grandparents, Lena and Theodore Scherer, near Olney, Illinois. Like any kid, you love the farm. You’re a busy little man there—gathering eggs, helping feed the cows, watching them work in the fields and pumping the player-piano in the parlor—pumping and pumping—learning the words as they roll by. And from your grandmother you learn the song of the land, of seed and sun and storm, of green-growing things and the harvest to come.

Back in Winnetka, when times are finally too tough to weather, you and your mother live with your Irish grandmother, Mary Ellen Wood, whose Victorian abode also harbors your aunt and uncle and their four children during these crucial years. From her you learn laughter. For all her years, she loves to go to Riverview Amusement Park in Chicago and you have hilarious times together riding the roller coaster there. When your grandmother dies unexpectedly, it’s your first experience with death. You become hysterical at the funeral and have to be taken away. You can’t realize she’s really gone. That night you add a postscript to your prayers, “And God please take care of Grandma.” You worry whether or not there’s a “roller coaster in Heaven.” You’re afraid she’s going to get “awful homesick” there. . . .

Now you’re eleven years old, Roy Fitzgerald and you make your theatrical debut in the fifth-grade’s Christmas play. You wear a long blue robe—a sheet dyed blue, with a hole in the middle for your head—and you barefoot it out on the stage as one of the “Three Wise Men.”

At twelve, you’re an ardent movie fan. Inspired by the movie “Hurricane,” you decide to be a movie star and really dream it up big. You watch wide-eyed as Jon Hall dives from the ship into the lagoon before the admiring eyes of Dorothy Lamour. An excellent swimmer, you literally live in the waters of Lake Michigan. This year, too, you’re the pride of Miss Pratt’s dancing school. You defend a smaller boy when some older ones gang up on him, and out of gratitude, his wealthy mother rewards you and insists on paying for some dancing lessons.

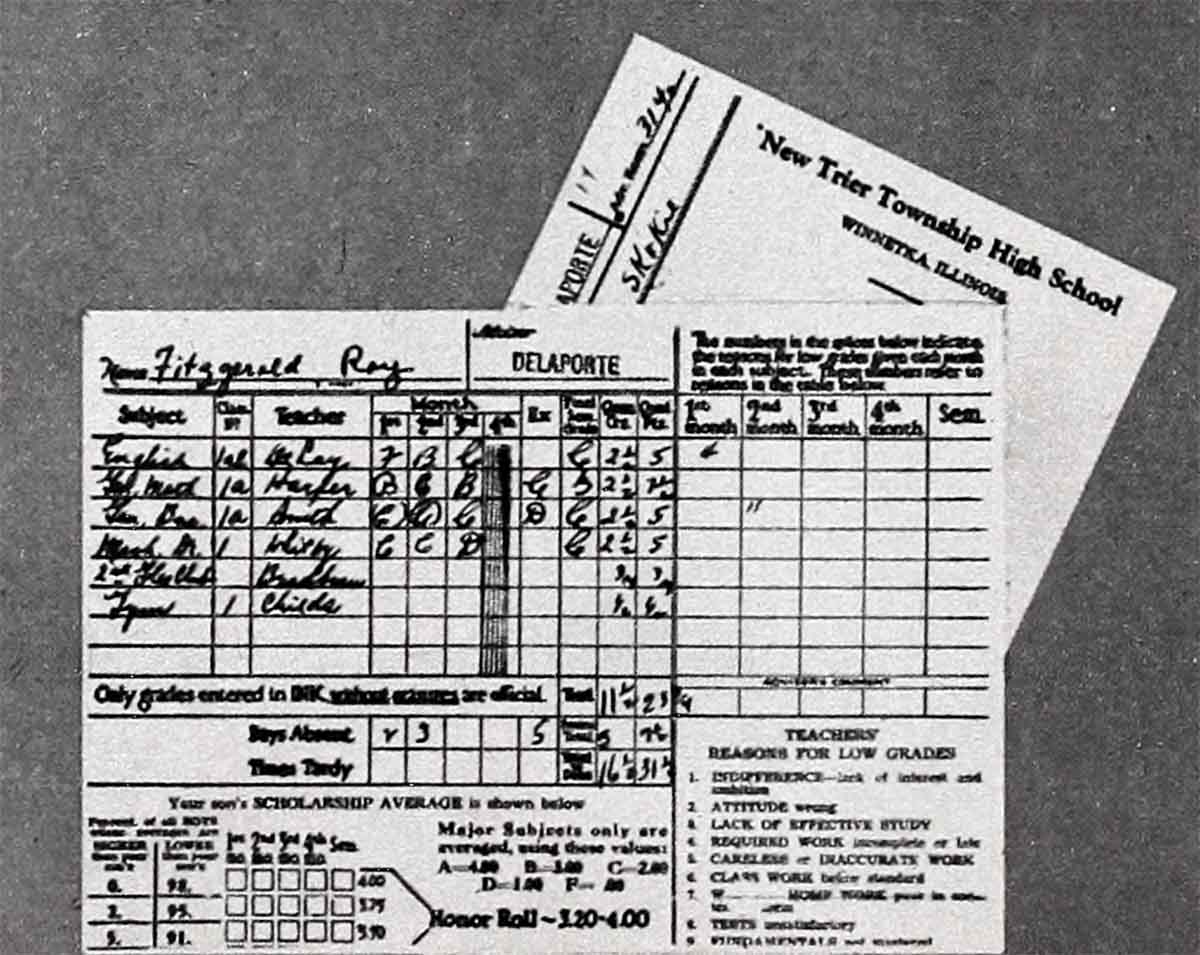

Here’s to the team—they’re the green and the gray—

Remember the New Trior High School fight song, Roy? You sing in the school glee club and in the First Congregational Church choir. You win many swimming medals in school meets. During the summers and after school you work as a caddy, soda jerk, window washer, short-order cook, and you’re employed by an awning company—but not for long. Lose your stripes, Roy?

“You can say that again, Ralph. I lost all the stripes—period. We removed awnings from in front of the town’s better homes and stored them in the warehouse for the winter. There were about a hundred of them and I stored them away without labeling them. When we went to put them back, no one could figure out which awning belonged to which house. We had some of the funniest looking houses around town that year. . . .”

Your companion in many boyhood adventures is your life-long friend, Jimmy Mateoni, who’s written something in the yearbook, “New Trior Echoes,” but I can’t quite make it out—

“I’ll tell you what it says, Ralph. ‘Lots of luck to a swell guy.’ Roy and I have a lot of good memories—like taking three lunch periods at school and a few adventures on which we embarked. Roy was always talking about going into the Army Air Corps then. One Saturday we went to Chicago to the Loop to enlist. But before we got there, we chickened out and went to see ‘The Road to Zanzibar’ instead—”

In high school you lose your heart to a pretty brunette with dimples and big blue eyes—over a hot fudge sundae at Cooley’s Cupboard, the school hangout in Evanston. Together you and Nancy Gillogly, Jimmy Mateoni and his girl, Barbara, are a steady foursome around town. You love to dance and you swing out in a mean jitterbug to the rhythm of “Chattanooga Choo-Choo”—but Barbara—now Barbara MacCrea of Westwood, California—can swing out better here—

“We used to go to ‘The Limehouse Tavern’ in Evanston, Mr. Edwards. They had a terrible three-piece-band, so we’d wait until the band quit, then we’d play Glenn Miller records in the jukebox and swing out on the ‘New Trior Hop.’ Roy and Jimmy were very good dancers, and sometimes driving home we’d stop the car, turn up the radio and dance in the street in front of the car lights. We had some pretty hilarious times. They were a comedy team anyway, Jimmy and Roy. One night coming home from a dance, Nancy and I stood guard while they took a For Sale sign from a vacant lot and transplanted it in the yard of a girl we were on the outs with at the time. Her folks had a lot of calls before they found the sign.

“We went to movies a lot then, too. Nancy and I were daffy about Alan Ladd. I remember when we went to see ‘China’ how we raved about Alan all the way home and Roy and Jimmy were so disgusted with us. Roy loved to eat, and we usually wound up at Cooley’s Cupboard. One night we stopped by for some fudge cake and coffee, then we ordered cheeseburgers and curlicues (they’re curly French fries), and topped it all off with banana fudge royal sundaes—”

Cooley’s Cupboard is also the scene of the tiff you have with Nancy—the night before you go into the Navy—which cancels the lingering farewell scene you’d envisioned for that particular evening.

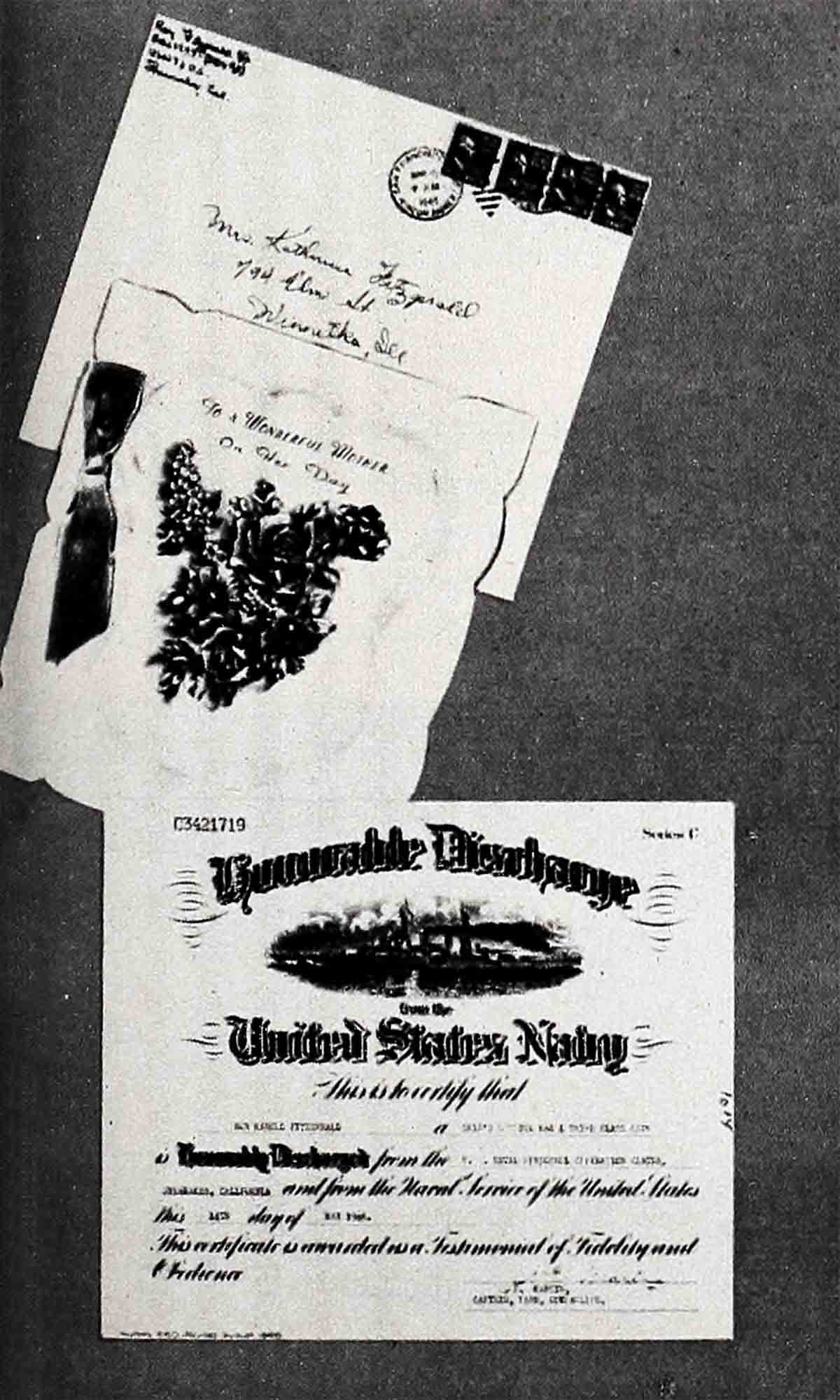

It’s 1944 now, Roy—and you’re also in hot water with the Navy. They’ve mistakenly marked you AWOL. You’ve finished boot camp at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station and you’re home on furlough, when you’re suddenly taken ill. The Naval Station sends an ambulance for you. But at the end of your furlough—when you don’t officially check back through the gate—those in charge there mark you AWOL. Later they send your mother a letter of apology when they find you in the hospital—but in the meantime, the Chief of Police in Winnetka and the Shore Patrol in Chicago have been notified. Your mother’s at work and the SP’s do a thorough job of searching the apartment, not, however, without some opposition from the janitor and his wife, who are devoted to you. The Shore Patrol comb the closets, look under the beds and in every cranny, until your friends can stand it no longer. “Where did you expect to find Roy—in the icebox?” they ask.

In 1945, you’re a long way from Winnetka Seaman 1st Class Roy Fitzgerald. You’ve seen service as an aviation mechanic in Guam and Australia and you’re now stationed in the Samoan Islands. You’ve just been transferred from fighters to B-29 bombers, and you have a little trouble with one of the big planes—

“Big trouble, Ralph. This was my first experience checking out multi-engine bombers and getting them flight-ready. Nobody had told me not to rev up two motors on the same side first. The plane jumped and completely demolished a Piper Cub on the field. For this I was transferred again—to the laundry. . . .”

In June you send your ‘mother $40 for a new dress and request her to send a dozen red roses to Nancy for her graduation. She sends some long-stemmed beauties, but your next letter says, “Mom, you sent the roses to the wrong Nancy. That’s what I get for not telling you everything.”

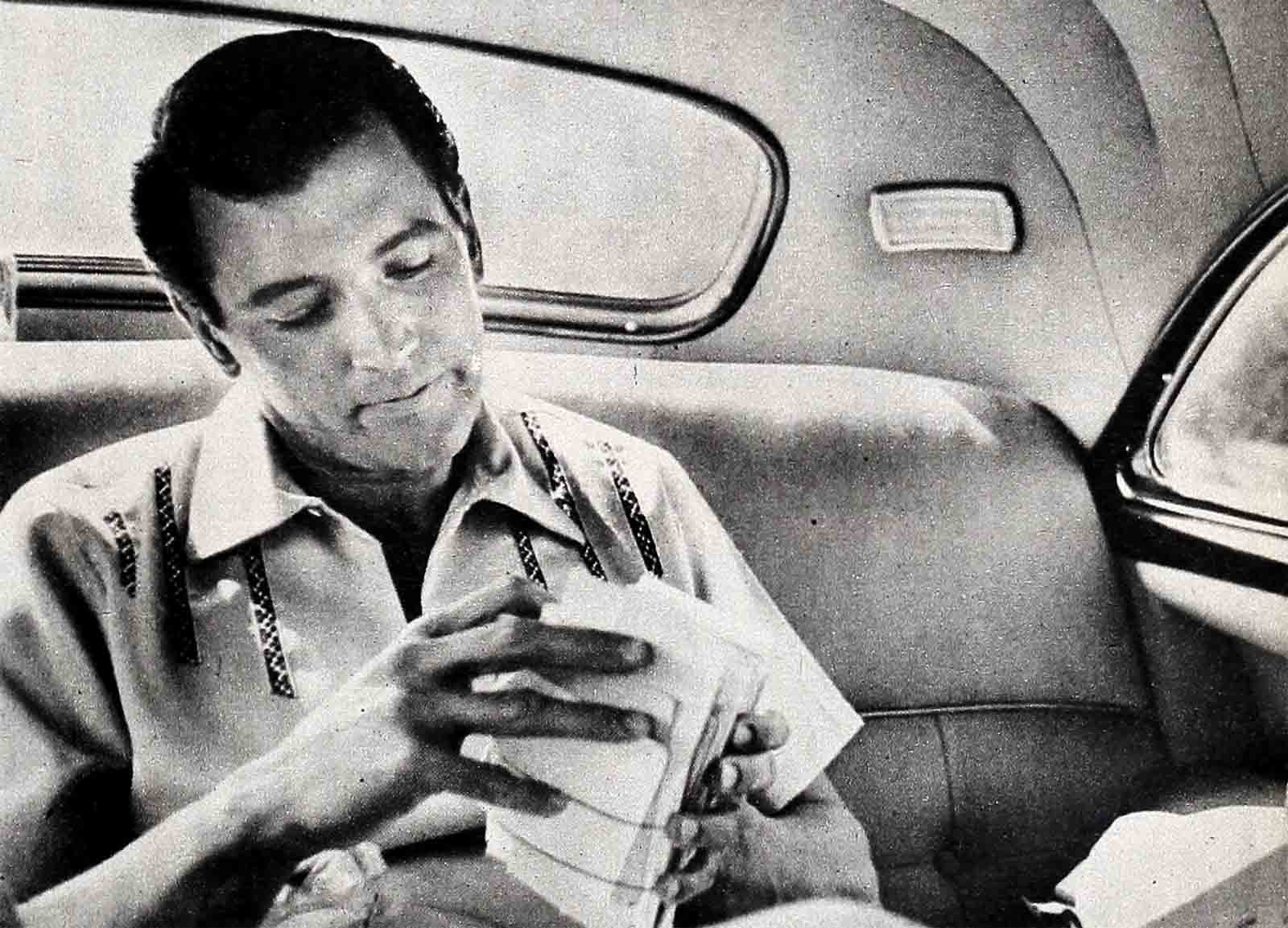

1945 just isn’t your year. You’re stationed in the Philippines when you get a letter from the right Nancy informing you she’s in love with somebody else. You feel pretty dejected and rejected. Slowly you turn the envelope to look at the date, then at the three-cent stamp. Now your pride is really hurt. You answer it immediately, saying: “The least you could have done was tell me air mail.”

The months roll on, Roy—it’s 1946—and you’re out of the Navy and back in Winnetka getting on your feet again, literally, as a substitute mail carrier. One customer—your mother—doesn’t get all of her mail. When she calls business houses asking why they haven’t billed her, she gets the same answer—“Your boy took care of it.” You’ve paid the bills and never mentioned it. On the other hand you “collect” from one of the ladies on your route, a family friend, Mrs. Augdahl—

“Roy was the cutest mailman we ever had, Ralph—and also the hungriest. I always had doughnuts and coffee waiting for him. I’ve known Roy for years. When he was a little fellow he was our paper boy. When Roy and his mother came back to Winnetka a couple of years ago, they stayed at our house and really put it on the map, in a matter of speaking. My granddaughters, Betty and Sharon Rottler, are great fans of Rock’s. They insisted on giving up their bedroom to him. Ever since then, visitors have filed through to see the bed Rock Hudson slept in—”

It’s still 1947 and your name is still Roy Fitzgerald. You pass the Civil Service exam with a 96 rating. You plan to be a full-fledged mail carrier but your mother is transferred by the telephone company to Pasadena, and hoping to get into University of Southern California on the GI Bill, you head west—into the sun. . . .

There are still dark and discouraging days ahead of you—

You can’t get into the university, so you’re driving a truck now for the Budget Pack Company, making $60 a week and sharing quarters with three truckers in an old family hotel near Westlake Park. Often you detour and pick up your mother to keep you company on the long route to markets surrounding Los Angeles. One day the chief operator puts through an “important” call to her. You’re bringing over somebody for her to meet when she gets off work, you say. Your mother can’t wait, envisioning no doubt the little wife-to-be.

“Mom, I want you to meet Lizzie,” you beam. Lizzie is a 1933 black Ford coupe with yellow wheels. . . .

Yes, having your own car is a proud day, but driving a truck isn’t the way you meant to travel through life. Not for that kid who watched Jon Hall dive into lagoons and daydreamed of making a name for himself in movies some day. You’re not even a name. You’re a trucker’s button with a number on it. This isn’t the big challenge, however necessary a chore, or the rewarding harvest that your grandmother talked about. Your only challenge around today’s next corner is a stop sign. Here you are now—living next door to that kid’s daydreams. Others have made it. Why not you? Just one thing holds you back right now—where do you begin?

You begin by borrowing $24 and having some portraits made. Somebody says Producer Sol Lesser, who headquarters at Selznick-International Studio, is looking for prospective Tarzans. On your next delivery to Culver City you park the truck and take the photographs in. On the advice of the switchboard girl, you leave them for Henry Willson, vice-president in charge of talent for the studio . . . and your agent today. Tell us, Henry, what impressed you—

“That magic indefinable spark, Ralph. The special twinkle a boy or girl has—or does not have—that makes them screen material and which you recognize immediately. Also, in Rock’s case, his physical appearance, his basic honesty and obvious enthusiasm. . . .”

During the weeks to come—whenever you have a delivery in this direction—you park your truck on a side street, then study with Lester Luther, Selznick-International’s drama coach. You pass famous faces on the lot—Jennifer Jones, Joseph Cotten, Shirley Temple—but in your dungarees, blue shirt and trucker’s button they mistake you for a studio laborer. David Selznick doesn’t want to sign you. Walter Wanger isn’t interested in you. Nor are others. But now you’re determined and you quit your truck-driving job to devote full time to the dream. . . .

It’s 1948 now. Your name is Rock Hudson, and Director Raoul Walsh gives you a screen test and a bit part in “Fighter Squadron” at Warners. The test is a sexy scene with Janis Paige for “Colorado Territory” and it’s good—so good that U-I later signs you on the strength of it. But Joel McCrea gets the part. You have one line in “Fighter Squadron” (pretty soon you’re going to get a bigger blackboard), and you fluff it over and over. But it’s your line, you’re doing something as an individual—not just a cog in a machine.

Two people believe in you—and they back up that faith. Director Raoul Walsh puts you under personal contract for $125 a week for 40 weeks. Together, Walsh and Henry Willson invest $9,000 in you, grooming you for a movie career. What sold you, Raoul Walsh?

“Rock’s looks, his sincerity and his naturalness. He’s a very natural actor. I figured the boy really had it. I had two more years to go at Warners and I didn’t want to hold him back. U-I made a deal, and we thought he’d get a break there. I’d brought him to the attention of John Ford, Hal Wallis and others, but they weren’t interested. ‘They all make mistakes, Kid,’ I told him. ‘Don’t worry. We’ll make it—’ But Rock wasn’t too discouraged, anyway. He had a great philosophical outlook. He could take the good with the bad.”

It’s 1949. You sign with U-I—and you call your grandmother Scherer who’s now living in Mobile, Alabama, to give her the good news. “Save your money, Roy.” she says. “You’re making $150 a week—”

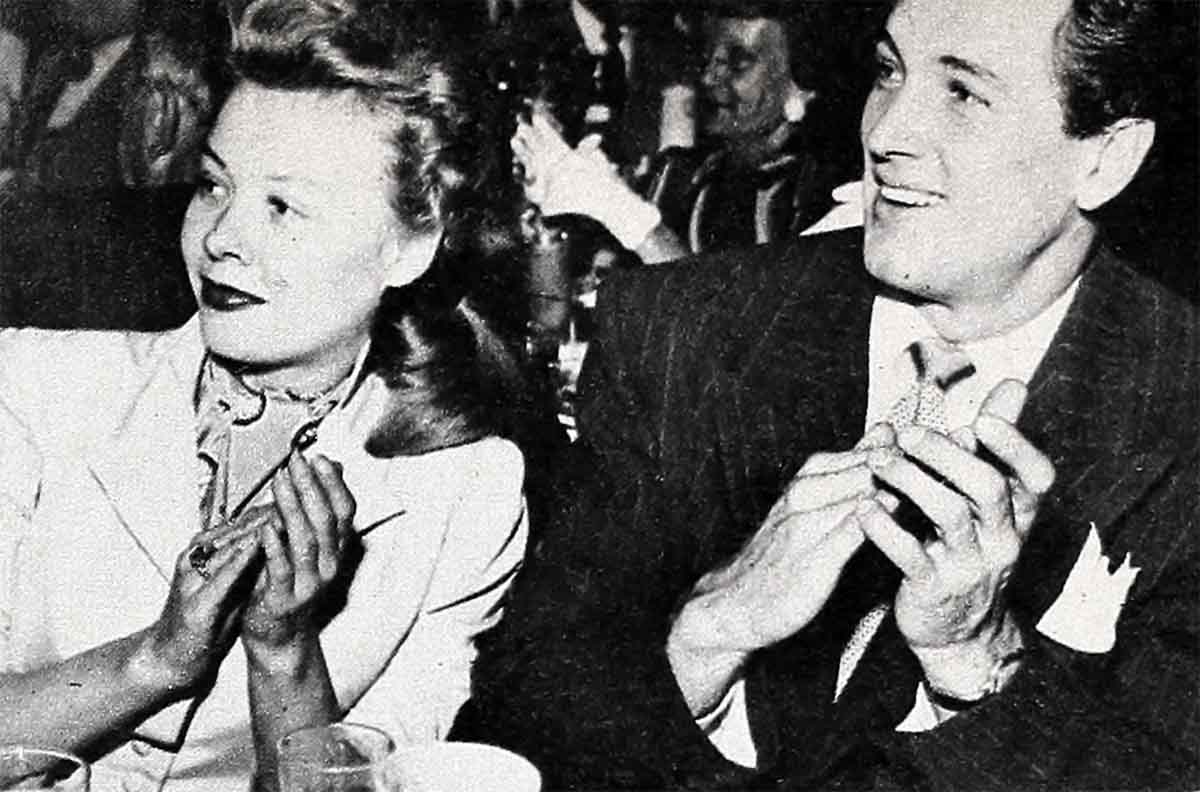

The months roll by—and the cameras roll with them. This is a strange and exciting new world. You get a few lines as a detective in one picture and portray a GI in the next. Gradually your roles begin to build. You see your first legitimate plays. You visit glittering bistros along the Sunset Strip—a long way removed from the Limehouse Tavern and the “New Trior Hop.” You have a serious romance with a glamorous motion-picture star—but Vera-Ellen’s $1,500 a week seems beyond your financial sphere. . . .

In February, 1950, you draw a Western, “Winchester 73,” and you draw, too. You can stay on the horse—but you can’t make your ten-gallon hat stay on. The camera rolls, you ride and your hat falls. In that order. Finally you’ve spoiled one too many takes. Then you hear a merry infectious laugh. The whole company joins in, the tension is broken and the shot secured. The laugh belongs to a radiant blond, the script girl, Betty Abbott, whose merry laughter and companionship will mean more to you in the days to be. . . .

Your faith—cornerstoned on an Illinois farm—is tested many times. You’re thrown by a horse and wrapped around a telephone pole with minor injuries. You’re stricken with appendicitis in the middle of a swashbuckling scene. You attract accidents—but you recuperate quickly. Your toughest fight is self-doubt, spawned by years of having had to try too hard, of living too long on little more than philosophy. You fear that you will never be good enough in your job. Never be the actor you want to be. For you know now, Rock Hudson, that this really is your life. . . .

And there are breaks, too, that come out of the blue—

In 1951—you get your best part to date when the studio needs a tall actor to play Jeff Chandler’s prize-ring opponent in “The Iron Man.”

This is the year, too, when a magic chant speaks stardom for you. At the opening of “Bend of the River” in Portland, Oregon, screaming fans chant, “We want Rock Hudson!” “We want Rock Hudson!” And you stop the show. Studio executives are impressed. You are agreeably stunned. You can’t believe it, can you, Rock?

“No, I couldn’t. And the following night I went back to see my public and make sure. I stood out in front of the theatre for some time. I was wearing blue jeans—there were no lights, no red carpet, no trimmings—and not a single soul recognized me. I felt pretty deflated for a few minutes. Then the humor of it struck home and I broke up—”

Modesty will get you nowhere, Rock—and everywhere. Julia Adams knows—

“Yes, I was there, Ralph. We’ve worked in four pictures together and they were fun. Emotions seem to come right out of Rock. That’s because he’s so intrinsically real. Reality comes right out of him. And he’ll never change. I’ll never forget when we made ‘The Lawless Breed’—how patient and helpful he was with Race Gentry. It was Race’s first time before the camera and Rock kept reassuring him—“You should have seen me my first day—Brother!’ When I mentioned giving up my house for an apartment recently, Rock offered to help me move. Id forgotten all about it when moving day came—but Rock hadn’t. He was right there. He worked like a stevedore loading and unloading all day. And believe me—such assistance is rare from any popular leading man. I’m so happy for Rock now. It’s wonderful when you see somebody go up and up—somebody so deserving and who can handle success so well. . . .”

By 1952 you’re going from picture to picture—without even time for a haircut. In September you’re in London, co-starring with Yvonne DeCarlo and directed by Raoul Walsh. You’re invited to a Royal Command Performance, and you—Roy Fitzgerald, the Winnetka flash—are presented to the Queen. If the cats back at Cooley’s Cupboard—could see you now. . . .

Your star keeps rising and 1953 is your most memorable year. You’re the idol of bobby-soxers everywhere. You’ve traveled across town from $60 a week to fame in four figures. Your fan mail has zoomed to 3500 a month. You’re at the top of the nation’s fan magazine polls. You’ve weathered your baptism of fire—in 21 films. But your darkest hour is still to come. . . .

You’re up for the pivotal part in Lloyd Douglas’ inspirational story “Magnificent Obsession.” But every important male star is trying for the role. If you get it—success would shoot you to dramatic stardom. But failure could banish you to the Indian reservation from now on.

Your studio faces a momentous decision. Would the public accept a bobby-sox hero in one of the most demanding dramatic roles in screen history? Would you measure up as Jane Wyman’s leading man? Would the switch from swashbuckling and gun-toting to powerful drama be too much for your years and experience? Their answer bespeaks an overwhelming faith in you. They give you the part without a test.

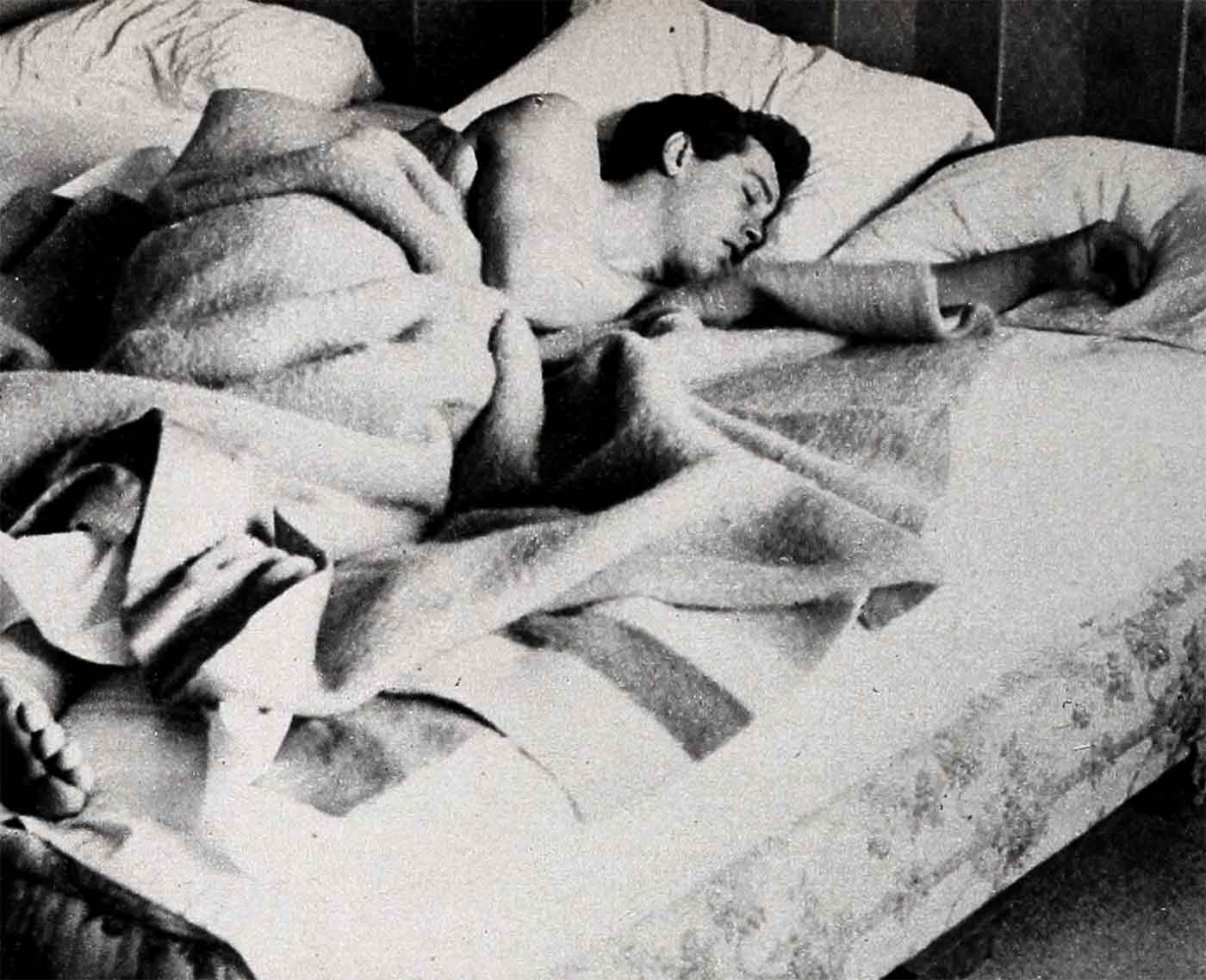

But August 31 your whole world falls. Your faith and your future are at stake. You’re at Laguna, riding the surf, relaxing for the rigorous role ahead, when a powerful breaker smashes you down on the beach, breaking your clavicle bone. Through the maze of pain and shock—as the ambulance sirens through to the hospital in Burbank—one thought tortures you. Will you lose “Magnificent Obsession”? How long can they hold the part? How long will it take your shoulder to heal? The doctor’s words are as the voice of doom when he hazards—before seeing the X-rays—it may take eight weeks.

You age two years this night, Rock Hudson. During the long, wakeful hours that dawn, your grandmother’s trust seems far away. You remember your mother’s words of comfort to a sensitive little boy, when she taught you The Lord’s Prayer. “You will be surprised, Roy, what it will do.” Only you and the Guy upstairs know tonight—how hard you are praying. . . .

On September 24, at Lake Arrowhead, the camera rolls on “Magnificent Obsession.” You have the cast off your shoulder and those first scenes involve running and being dragged out of the lake—physical scenes. Somehow you get through. Betty Abbott knows how uncomfortable those first days are for you—

“They were pretty rough, Ralph. Being around water isn’t too good for any fresh injury. During one shot on the beach, Rock leaned on his arm. When the scene was over he couldn’t move his arm or his elbow. That night a big lump welled up. He was afraid he might be paralyzed and not be able to finish the picture. At first he was concerned, too, about what he could contribute to a cast feeling like that. Rock’s a great artist at heart. He’s highly emotional and sensitive to the reactions of other people. At the premiere of ‘Magnificent Obsession,’ dear old Rock was counting the coughs in the audience. If anybody coughed he was sure they didn’t like the picture. Finally he noted they were coughing between the scenes, he felt better—”

For you, Rock Hudson, “Magnificent Obsession” determines whether you have what it takes. Whether you belong here.

You’re grateful when such established stars as Jane Wyman, Agnes Moorehead and Otto Kruger welcome you from the first day with open arms. According to Otto you had no cause for worry—

“That was the marvelous thing about him, Ralph. From the first day, Rock had both hands out all the time—wide open— for any suggestions or advice. He had a terrific problem and he knew it. It’s that kind of part. I remember when Bob Taylor came into my dressing room years ago and tossed me the script, saying, ‘Pop—look at this. Look what I’ve got to do. I can’t do it—’ All you have to do now is show any actor the script of ‘Magnificent Obsession’ and tell him, ‘You’re going to play this part’—Rock’s part—and he’ll die. And Rock really played it. Its a wonderful thrill for an older actor to see a young one, someone who’s struggled through cowboy and Indian things, get into a real thing like this and then lick it completely. I couldn’t pick out a flaw—”

It’s January 11, 1954. “Magnificent Obsession” is sneak previewed at the Encino Theatre in San Fernando Valley for the first public reaction to the picture. The word has gotten around. There in the darkness many are pulling for you. Yours are suspended emotions. The next two hours will decide the rest of your life—

When the lights go on, you make your way in a daze through the crowd. Your eyes are filled with tears, but you don’t want anyone to see. is is a moment too sacred to be shared. You go out into the dark parking lot among the cars back of the theatre, to get over the first emotional impact. For the first time, you realize that Roy Fitzgerald of Winnetka, Illinois, may actually be somebody. That your dream can be reality. This is your life—

The word spreads over Hollywood like wild fire—a new dramatic star has been born. Director Douglas Sirk won’t take the credit for the delivery.

“I had a great conviction from the first that Rock was right for this part—and he lived up to my expectations. He gave a wonderful performance in depth, warmth and honesty. But that camera has an X-ray eye. It’s a case of being the part, too. If the ability and feeling isn’t there already inside, no director on earth can get it out.”

Take Jane Wyman’s word too—

“He’s a young man to assume so mature a part. Rock has a wonderful depth and a fine dramatic knowledge of things. Let’s face it—the man couldn’t do it if he didn’t have it. . . .”

You have it all right, Rock Hudson. Deep inside. You can bless now all the things that have happened to you, that have mellowed you through the milestones of your 28 years. . . .

On April 19, among blazing klieg lights, excited fans and a brilliant throng of stars and critics, “Magnificent Obsession” is premiered and within minutes, the whole world is to know the victory that is now yours. This is your triumphant hour. Here beside you are two who belong in that hour. One is Betty Abbott. The other, standing with pride in her eyes for the whole world to see, is the person who shared in so many milestones along the way—“I want you all to meet my mother—”

Near in your heart is another—your grandmother—who fostered the faith that today’s dawn finally would come. . . .

For you, Rock Hudson, the harvest is here.

THE END

—BY RALPH EDWARDS

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1954

vorbelutr ioperbir

4 Temmuz 2023F*ckin’ amazing things here. I am very happy to look your post. Thanks a lot and i am having a look ahead to contact you. Will you please drop me a mail?