Why Try To Change Me Now?—Jane Russell

Shortly before she left for Europe this fall to star in the first Russfield production, Gentlemen Marry Brunettes,Jane Russell sat with a couple of friends in her beach house at Malibu. The dove-and-pink livingroom with the clean modern lines has almost become a trademark of hers. This was during the time that she was making Foxfire with Jeff Chandler and, as always, Jane was dog-tired midway through the picture. She isn’t a girl who takes her film emoting lightly. Because she was tired, she had done what she always does when a blessed free week-end unfolds—beat feet for the seashore.

It was particularly quiet there that Sunday afternoon. After an active morning on the beach, her kids, Tracey and Thomas, had needed no urging to fall into bed for their naps. Robert had gone fishing with a couple of cronies. The beach house had no telephone, no TV set, not even a-radio to invade one’s privacy. There was only the hypnotic tone of the surf beyond the picture window . . . only the bittersweet nostalgia of the blues coming softly from a pint-sized phonograph on a nearby table—and Jane Russell sitting quiet, her dark eyes brooding over the sea she loves so well.

Suddenly she spoke, shattering the illusion of serenity. “Next time a writer asks me for a story idea,” she announced, “I’m going to come up with one for him. A story to be called If You Don’t Like It, Lump It.”

Ah, ha! you might well think. Now that she has formed her own picture company, now that she isn’t tied down by a contract, Miss Jane can’t concern herself with what the public says.

No such thing. In spite of, or perhaps because of, the controversial storms she has shrugged her way through with apparent indifference, Jane has always needed approbation more than most movie stars. She goes out of her way to avoid antagonizing people, she cares. very deeply how the public feels and she isn’t about to develop one of those “I’m-bigger-than-all-my-critics” complexes.

There was a reason for her saying what she said, however. One of the friends relaxing with her that Sunday was a writer, who had been giving her some tiresome, uninvited “for your own good” advice about a certain current Russell project which had nothing whatever to do with the making of motion pictures. The unwanted counsel had been offered some hours earlier, at which time Jane neither sulked nor argued her point. But now she came up with this like-it-or-lump-it routine. Although it was a pretty sneaky way of telling a friend to go climb a tree and not up to her usual standard of forthright insult, there are mitigating circumstances. First, she was tired. Besides, the writer was a guest in her house, and Jane is never rude to guests. Well, hardly ever. And finally, she wasn’t mad at anybody. She made the remark without a trace of malice, and when comprehension dawned on the guy, she grinned at him toads Just so he knew where she stood.

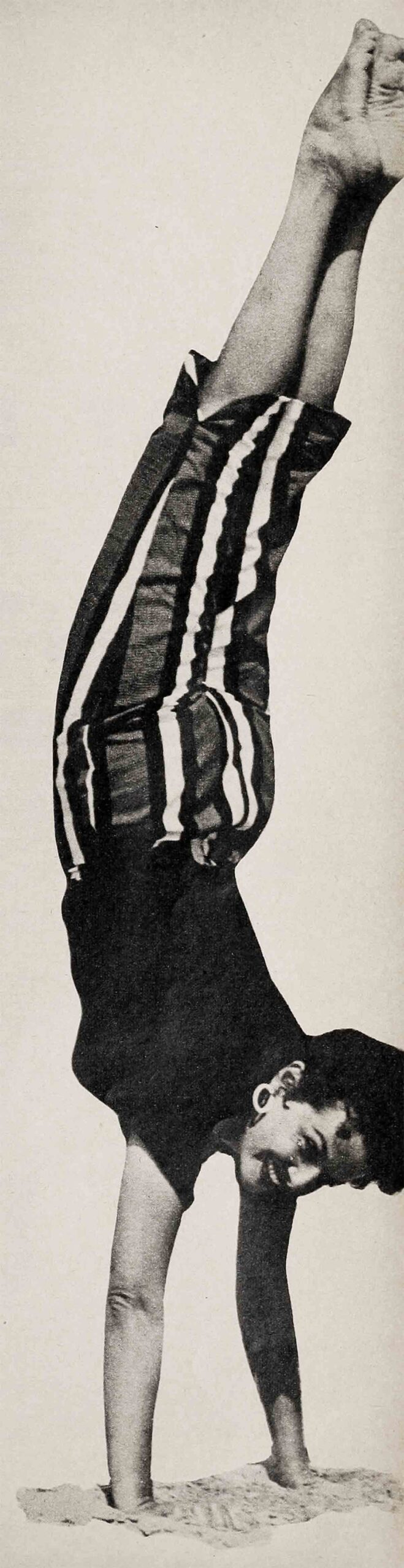

Where she stands is on her own two feet. She’ll make mistakes in her newfound independence, maybe, fall flat on her face, maybe, but the point is that at least they’ll be her mistakes. One of the things Miss Russell is most tired of is being slapped on the wrist for obeying orders. “If people think a thing is in bad taste, it’s their privilege to make a fuss—but before they criticize me or anyone else for what they see on the screen, couldn’t they at least ask whether our contracts permit us to object-to scenes in the picture? I can insist on script changes now, but I couldn’t always.” This is one desirable aspect of independence, but it has its drawbacks, too. With the announcement that she wears no man’s collar, any future goofs must be laid at her own door.

Of course, what constitutes a goof is a matter of personal opinion. Earlier this year Jane made a trip to New York and, on a nocturnal search for some real crazy music, ran into a columnist who reported the following day that Miss Russell considered the Almighty “a Livin’ Doll when you get to know Him.” A national magazine duly noted the comment, and there were sanctimonious howls of outrage at her blasphemy and retorts from cooler heads pointing out that if Old Jane knew the Lord well enough to call Him a Livin’ Doll, she was in much better shape than people who didn’t know Him at all. Jane was mildly surprised but not at all upset by the to-do. “I guess I did say it,” she confirmed placidly. “It sounds just like me—why, you’ve heard me say it a hundred times.” She doesn’t regard that as one of her mistakes. But she’s a wicked one, all right. At the end of her nightly prayer she has even been known to implore the Lord to take care of Himself.

When magazines break out in a rash of stories asking whether success had changed Jane Russell, they’ll just be words. Currently the Old One’s (Miss Russell’s four brothers’ pet name for her) favorite song is a standard called, “Why Try to Change Me Now?” and it ought to be her theme song. Nobody is going to change Jane, for her own good or otherwise. She’s as stubborn as a mule, unshakable in her loyalty—and she’ll stay that way. She indulges whims she knows will land her in hot water up to her chin. She always listens to people who know more about making movies than she does and, unaccountably, she sometimes listens to people who wouldn’t know a camera angle from a hole in a doughnut. She’s convinced that she’s a sound judge of character and yet, jokingly or not, she sets quite a store by astrology. “I don’t even know why I like you,” she often complains to one of her friends. “Everybody knows that Geminis can’t stand Taureans!”

She’s curious as a squirrel about strangers—some strangers—but never try to make book on which ones will appeal. When they don’t, she ignores them. “I’ve never been so embarrassed in my life,” relates a member of the RKO publicity team. “We were in the gallery, shooting some art for a magazine cover, when the editor of the magazine came in. I introduced them, and Jane said, ‘Hi,’ in that disinterested voice that I ought to recognize by now. Then she proceeded to look right through that woman for two hours. I nearly wore myself out trying to make small talk.

“Still, you can’t get mad at her. After all, just to do these pictures, she was giving up a day when she could have been at the beach. She made every costume change we asked; she did everything the photographer said. Only her mind was somewhere else—and if I had said anything to her about it, she’d have answered with something sarcastic, like, ‘Who’s going to put my mind on a magazine cover?’ You can’t change that dame.”

When she thinks a stranger is bright or cute or funny, believe it or not, Jane is shy. The high-voltage eyes look hither and yon, sneaking only an occasional glance of appraisal. She becomes a model of decorum, causing studio representatives to shift uneasily in their seats.

If she’s satisfied that this one is worth the time, for instance, she might pull a complete switch in the next moment and become the Legend. This myth, perpetrated and carefully nurtured by her devoted crew, insists that Miss Russell is mean as a snake, arrogant, temperamental, unreasonable—and her mother should bite her when she gets back to the kennel. No one can become a crew member in good standing without adding to this canard.

One Legend victim was a serious young man who came out from New York to write a story about The Real Jane Russell. He was introduced to her in the RKO commissary and they talked briefiy, but Jane was. bored, indifferent, uncooperative—which to the initiated meant that she liked him and was feeling playful. Calmly she outraged his artistic integrity by suggesting that he go on home and create any little piece of fiction that came into his head.

Smarting somewhat, the young man persisted. He was bound to write nothing but The Truth. Finally, Jane shrugged. “If you want to know what I’m really like, why don’t you go over to the set and talk to my crew? I guess they hate me the best.”

The crew greeted his appearance with fish-eyed coolness, and when he diffidently explained his mission, they responded with variously uncouth noises of derision.

“Why waste our breath, telling you what she’s really like?” scoffed hairdresser Steffi Garland. “When your story came out, it would be the same old watered-down version!”

“That’s not his fault,” stand-in Carmen Nesbitt pointed out sympathetically. “If he wrote the real story, they wouldn’t allow it in the mails.”

Behind his horn-rimmed glasses the young man’s eyes were beginning to glaze ever so slightly, a fact which the crew noted with complacency. They led him to Miss Russell’s portable dressingroom, sat him down, and began relating the reasons why she was an impossible employer.

At this point Jane entered. Although there was some shifting about to make room for her at the dressing table, she was otherwise ignored. She glanced in the mirror at the writer and asked, “Well, what have they been telling you?”

“Uh—nothing,” he lied uncomfortably.

“That doesn’t surprise me,” Miss Russell remarked, applying mascara with a deft hand. “I’m surrounded by fools and idiots.”

Nobly the writer stepped into the breach. “Miss Russell, there’s something I’d like to ask you about. In looking over your studio biography, I ran across something rather peculiar. It said that when you were a baby, your mother used to leave you out in the snow in your buggy for hours on end. Would you—”

“What’s so peculiar about that?” interrupted wardrobe mistress Mary Tait. “If you had given birth to something this horrible, wouldn’t you encourage pneumonia?”

It broke up the whole bunch, Jane Russell most of all, and gave the writer his first indication that they were pulling his leg. To date Jane has given her best acting performances as the Legend.

The real Jane Russell is so untemperamental and so cooperative that she feels defensive about making a reasonable adjustment in her daily routine. As everyone knows, she habitually tries to do too much, and has cracked up on several of her recent pictures. Worried, her family and friends persuaded her to cut down.

“Say, Old One,” teased a friend who didn’t know the circumstances, “you been taking lessons from So-and-so?” naming a star well-known if not well-liked for the regard in which she holds herself.

For once, Jane didn’t smile back. “Taking lessons in what?”

“Well, all of a sudden I hear Russell does not permit luncheon interviews—”

Jane looked stricken. Then, “I don’t,” she said tightly, “and I haven’t on my last two pictures. I just have a sandwich in my dressingroom and use my lunch hour to rest or pray or cry or whatever I feel like.”

It’s probably the smartest move she has made in years, and there isn’t a reason in the world why she should feel uncomfortable about it—except that she always has given up her free time in the past. The way it used to be, Jane was up at the crack of dawn in order to drive in from the valley and arrive at the studio on time. She worked through the morning, ate her way through a lunch interview, and hurried back to the set to work all afternoon. Usually there were other writers visiting the set, waiting to talk to her between scenes, and a member of the RKO publicity department once tabulated forty phone calls—all urgent—that came in for Jane in the course of a single day. Small wonder that she cracked up.

Now she has cute Penny Sweeney of the dandelion coiffure to screen the calls and the visitors, and she keeps her lunch hour free. Know what she does with it, besides resting, praying and crying? She answers the calls that worry her the most.

Let’s say that you’re in trouble. The phone rings, you answer, and this flat, unemotional voice says, “Hi. This is Jane. How are you today?” After the first time, you won’t need to be told who it is. After the third or fourth time you stop puzzling about the rest of it. There doesn’t have to be a reason why she concerns herself with you; she just does. Her voice doesn’t ooze solicitude with every syllable, she doesn’t comfort you in wildly affectionate terms of affection a la Hollywood, she doesn’t preach the gospel. Instead, she says with simple, hard-headed logic, “Look, do you have a really good doctor?” Or lawyer or candlestick maker, depending on your particular need. “. . . Because if you haven’t, mine is the best.” It’s entirely possible that Jane’s doctor, lawyer and candlestick maker do more charity work than professional philanthropists, and apparently they’re happy about it. They eschew payment for whatever service they have rendered warmly but firmly. “Anyone who’s a friend of Jane’s—” is what they say.

Of course she believes in miracles and kill-or-cure methods, There is a reporter in Hollywood rumored to be sitting in a corner, gibbering to himself and playing with a piece of string, on account of Jane. It seems that he had a blue-ribbon assignment on her, one of those directives that said, “IMPERATIVE. DROP EVERYTHING ELSE. DEADLINE.” So he went to U-I to visit her on the Foxfire set.

He was moping around her dressingroom when she came in, and immediately Jane asked, “What’s the matter with you?”

“I dunno,” he answered. “Picked up some kind of bug; I guess.”

“So what are you doing here?”

“Well,” the reporter was vague, as reporters usually are, “I had this assignment on you.”

Jane clobbered him with a look. “I’m not going to talk to you,” she said with absolute finality. “You look horrible. Go home and go to bed.”

“But my story—”

“I said, go to bed. I’ll call you later.”

She did. She called that day and the next and the next. The second day she had a personal physician at hand. The third day she turned up with the most novel idea in publishing history; she had a writer from a competitive publication in her dressingroom when she called. “I told him about you,” she said, “and he says he’ll be glad to help you out in any way he can. Write your story for you or anything.” Big joke.

The only thing she was steadfast in refusing to do, over the telephone or otherwise, was to hold still for any interview. “My doctor says you’re too sick to work,” she said stubbornly, “and if I don’t give you any material, you can’t write a story.” And if he didn’t write the story, he’s probably peddling pencils on a street corner, or playing with that piece of string.

But why try to change her now? She’s a magnificent, complex creature of fantastic impulses and pedestrian caution which are almost always in conflict.

Like quicksilver and the sea, Jane is changeless. She’s only in a different mood right now. A grave, adult mood acknowledging that this might well be the most important year of her life. For the first time since she appeared on the Hollywood scene, Jane is a free agent.

While she was under contract to Howard Hughes, Miss Russell probably didn’t realize how relatively sheltered she was. When she read a script, she didn’t have to look into a crystal ball and decide whether the picture would be a hit or lay an egg; she merely had to play the role written for her. The outcome involved neither her money nor any responsibility.

Now that’s all changed. She and Bob Waterfield will sink or swim on the strength of Russfield, and Robert admittedly knows nothing yet about making movies. Jane has got to read a script and visualize a picture, buy it or turn it down. Dicker for co-stars and directors. Rely on her own judgment regarding promotion, publicity and a dozen other facets.

It’s enough to make anyone serious, but Old Jane faces the future confidently because she labors under the delusion that she has mastered a very dirty word: compromise. She hasn’t, of course, since in her books compromising doesn’t include making concessions or ending up with anything less than she wanted originally.

How does she compromise? “Well, take music. Bob Thiele of Coral likes me to make a certain kind of record a certain way. I like to make another kind my own way. So I do four that he wants, and then he lets me do four of my own.

“Or in picture making. Universal wanted me for Foxfire and we want to borrow Jeff Chandler for a Russfield production. So we compromised.

“Or in private life. If Robert wants to go fishing in the mountains and I want to go to the beach, we can’t do both so we compromise—he goes fishing and I go to the beach.”

She was perfectly serious, explaining all this, although in every instance she cited, Jane Russell ended up getting what she wanted. Apparently “compromise” means the difference between getting what she wants immediately or five minutes later.

Lazily, the Old One smiled, and her eyelids dropped to cover some secret thought of her own. “But I’ll let you in on something. There are some situations where it looks like I’m compromising. I let people think I am. Only, I’m not—I’m just bidin’ my time.” The thought had mischief in it, but why try to change her now?

THE END

—BY TONI NOEL

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1954

No Comments