Hits And Hisses

I was the one, way back in October of 1941, who originated the idea which has subsequently caused more cat-calling, more name-throwing, more general mayhem than almost any other little factor in Hollywood.

As president of the Hollywood Women’s Press Club, I was the hapless one who suggested that our organization should give an award to the most co-operative female and most co-operative male star of the year. Since the Club was then, and still is, composed entirely of working press women, plus working feminine press agents, I thought it would be nice for us to say thank you to the stars who had been most gracious in granting interviews, sitting for photographs and being all around helpful.

If I had left the idea at that, the award would probably have passed quite unnoticed in the welter of other complimentary awards made every year. But no.

I was foolhardy enough to suggest that we also name the most un-co-operative stars of the year. The motion was duly seconded. The vote was passed—and all I can say now is that we, as a Club, didn’t know our own strength.

Not then—or not now. For we rock under the blows we get yearly from the particular studio that houses the particular star or stars who receive our sour-apple award. We seldom get thanked by the studio whose player wins our golden apple—that is, the award for being most co-operative. But how bitter are the cries from the criticized camps!

This year was no exception. Esther Williams, who, for the second time, was tagged the least co-operative actress is, for the second time, protesting violently. She offers what she considers a perfect alibi for being less than helpful to the press. Says she, “I’ve made a picture and had a baby. How could I have had time to be more co-operative than I was?”

That sounds like a reasonable enough response—until you consider the case of Virginia Mayo. This year Ginnie was (for the second time, too) the runner-up for the most co-operative award. And she was hardly loafing. Despite making two pictures and having her baby, she was always able to manage time for an interview or a photo sitting—never too busy to talk with a reporter personally.

And the pair who took the golden apples home—Dale Evans and Roy Rogers—have, possibly, one of the fullest schedules in town. They have a house full of children. They do pictures. They do radio. They do TV. And personal appearances. And benefits. The press demands on their time are almost unbelievable, what with reporters and photographers of not just one medium, but three, besieging them constantly. Yet, they somehow always manage to be gracious.

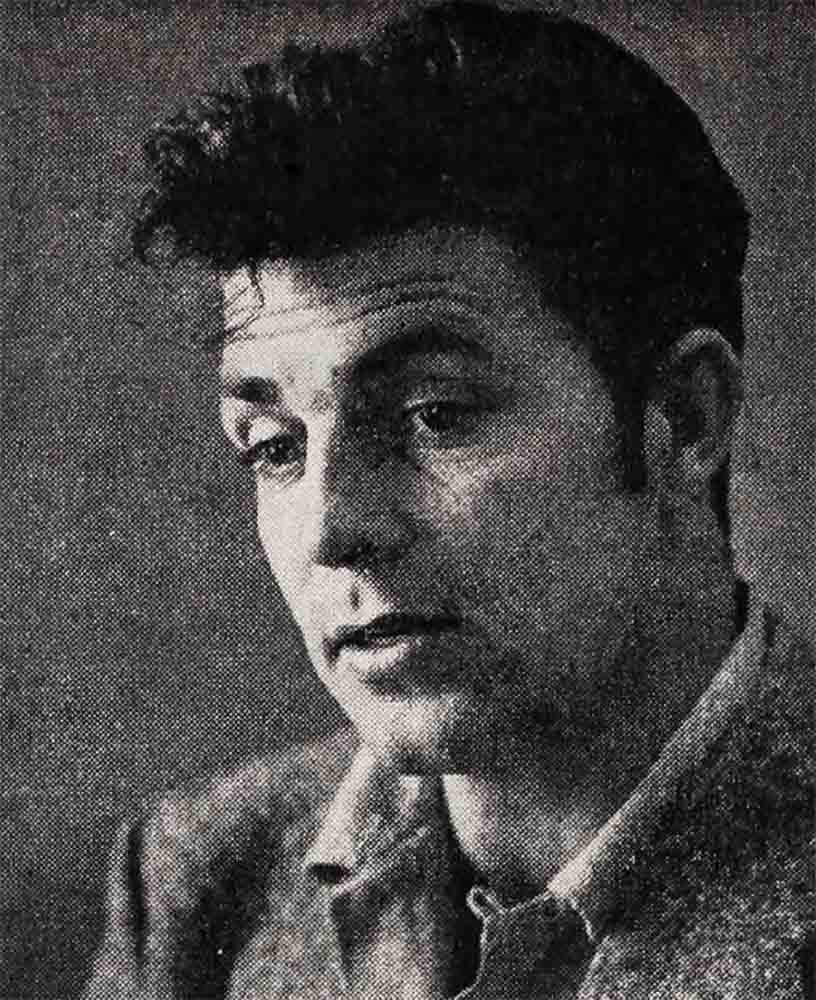

The same holds true for almost-winner Jeff Chandler. He chalked up four pictures last year and, in addition, was deeply entangled in a morass of domestic problems. But none of that stopped him from working generously with the ladies of the press.

His attitude is at the opposite extreme from that of Dale Robertson, who was handed the sour, sour apple. Although his studio, Twentieth, is obviously not happy about this award, it has not complained for it understands the justice of our choice.

I remember the first time I ever talked with Dale professionally. He was brand new then, and I interviewed him together with Mitzi Gaynor, who was equally new. Dale shocked me at the time by saying, “I’m in this business only for the money it earns me.” Mitzi was even more shocked than I. “Oh, Dale,” she said, “you know you have to be madly in love with this business to endure it. You have to give to it as well as take from it—and you know it.”

“Not me!” said Dale. “I’m after the dough. That’s all.”

And, sadly, that does seem to have been all so far. The sour-apple award is just one evidence of a point of view that can prevent Dale, no matter how talented and handsome he is, from being the top star he ought to be.

He has not, incidentally, made a single objection—at least not one that we have heard of—to his prize. He probably knows that he really deserves it.

His silence on the subject reminds me of the only amusing reaction the Women’s Press Club has ever had to its sour-apple award. It was back in 1944 when we pinned the least-co-operative tag on Sonja Henie, and, as a result, were confronted directly by her boss, the witty William Goetz, then head of International Films.

Before I go on, let me explain that our golden apple is really solid gold, a lapel pin for the girls, a golden script marker for the men, all duly engraved with our happiest sentiments and the winner’s name. But we don’t give anything as a memento for the un-ro-operative award.

“Doesn’t Sonja get a thing?” moaned Bill Goetz. “Can’t you give her a scroll or something, so that I can hang it up in the studio lunch room where all of us can enjoy it?”

Bill was just being more forthright than Paramount, who will now admit they felt delighted when we leveled out at Joan Fontaine in 1943. But they didn’t say so then. Joan was at the top of her form in those days. The smash success of “Rebecca”; an Oscar for her work in “Suspicion,” were just behind her; and the equal smash success of “Frenehmen’s Creek” just ahead of her. And she was, as stars so often are under those circumstances, feeling her oats.

She was, in fact, Miss Big. She had people fired right and left.

On our part, we had to get news of her—and we couldn’t. So we gave her the knock—and I must say, she listened. She’s smart, this Fontaine. When she saw the miles of unwanted published words the sour-apple title got her, she reversed herself. As a matter of fact, she went so completely out of her way to be gracious that we gave her the most co-operative award four years later.

The studios that yell loudest when their stars win the sour apple, try to imply that it is the Hollywood Women’s Press Club who damage their stellar property. But they really know, as we do, that our award only reveals the stars’ unwillingness to give any “plus” of their personalities to the public. These stars have come to the point where they no longer want to be known as human beings but as something special—“artistes.”

I’ve yet to see a star reach that point and recover from it completely. All of us who make our livings in Hollywood understand what produces it, and, what’s more, I’m sure that in the same spot we’d find it tough to resist succumbing to it ourselves.

It is a combination of too much adulation, too much money—and often, too little background. That it doesn’t happen to every star is a miracle. Take two of our standard pets—Martin and Lewis. They’ve had more fame, more adulation, more money than probably any two people since Napoleon.

Yet, somehow, these two kids have kept not only their heads—but their hearts. They work all the time—but they are never too busy to talk to any reporter, or pose for any photographer who comes on a legitimate mission. Jerry and Dean realize that our requests have nothing to do with us personally. We are acting on orders from our editors, who, in turn, are acting in response to public demand. When a star [urns down a legitimate request from a reporter or photographer, he’s actually turning down the public.

Bette Davis never got too big for her fame. Nor Bob Hope. Bob was our first winner, in 1941, as Bette was. He won again in 1943. The same is true of Alan Ladd, our winner in 1944 and again in 1950, and of Joan Crawford who won in 1945 and 1946 and could win every year, as far as we are concerned. That she hasn’t been a winner in the last few years is only because we’ve had fewer requests for stories on her.

This question of requests is vital in our voting—and it means that both our winners and losers will always be top box-office stars. We check the number of demands for interviews and photographic sittings before the personalities’ names ever go—pro or con—into our initial balloting.

A nice guy like Aldo Ray, let’s say, obviously gets fewer requests to make with the quotes than our raspberry boy of this year, Dale Robertson. So, naturally enough, Aldo finds it easier to be co-operative than Dale—though why Dale has to be as brusque as he is I’ll never know.

The usual argument is the one Esther Williams used this year—too busy—too much work. That was Greer Garson’s alibi when we landed on her in 1945, and Bob Mitchum’s in 1950, and it is always Frank Sinatra’s, to whom we gave the icy nod in 1946 and 1951.

But actually, how busy can you be, when you work six to eighteen weeks at the most per year? A top star, like Bogart, whom we sour-appled in 1949, or Gary Cooper, our villain of 1947, usually makes only one picture a year.

You, the public will pardon the working press I’m sure, if I tell you we yawn slightly when we are told how hard these stars work. Yes, I know about the nervous toll when they are shooting; it is rough. But I imagine you aren’t exactly pepped up after your day’s work.

The living end in un-co-operativeness are Fred Astaire, George Sanders, Errol Flynn and Frank Sinatra. Of course, nobody cares too much anymore if Astaire talks or not, and the same goes for Sanders. And I’ll bet Errol Flynn would be pleased to be asked for an interview—but Frankie!

An illustration of Frankie’s attitude is a kind of sad joke on our Club. Because of his fine work around the military camps during the war, we awarded him a special scroll. He wouldn’t even come over to pick it up! This is the complete opposite of Cary Grant’s kidding, which takes the pleasant form of his insisting upon being our sole male entitled to club membership, and who year after year, has acted as Santa at our Christmas party.

A couple of years ago, to our intense surprise, Bing Crosby turned up under Santa’s whiskers at our holiday hoe-down. Bing has never quite won our least co-operative award, though he’s an eternal runner-up, and I personally think that is because, as tough as he is to get to, always, once you do get there, he’s great. Bing is a business man. Interviews or portrait sittings are business.

Bing knows exactly what will fit into the time he’s allotted you. He says hello, gives out with well-nigh perfect material for exactly this time length, says goodbye. It’s not like the warm, friendly greeting you get from Bob Hope. Maybe that’s acting—but it sure is agreeable.

Of course, in this classification, there is no one like Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh, our golden-apple winners last year. Those two kids will do anything for anybody any time and do it smiling.

Glenn Ford is always available—and he even comes to your house to be interviewed, instead of making you come to him. We are all waiting for June Haver to return to the screen—because she has always been so thoughtful. So have Loretta Young, John Derek and Bill Holden.

As for Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, particularly with the sorrow they have recently experienced, they are just superb.

So there’s the story in a nutshell. Maybe you agree with our finds. Maybe not. But no matter what—the Hollywood Women’s Press Club is completely sincere—and honest—about the choices it makes.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1954