There Is No Jeff Chandler

Most people think they can tell a lot about a person by the way he looks. You figure a small, balding guy has. to be a hen-pecked milquetoast, and a big-busted, lush girl must be a sex boat. But it ain’t necessarily so. The little fellow may turn out to be a lion, and the size 38 can be nothing but a mouse.

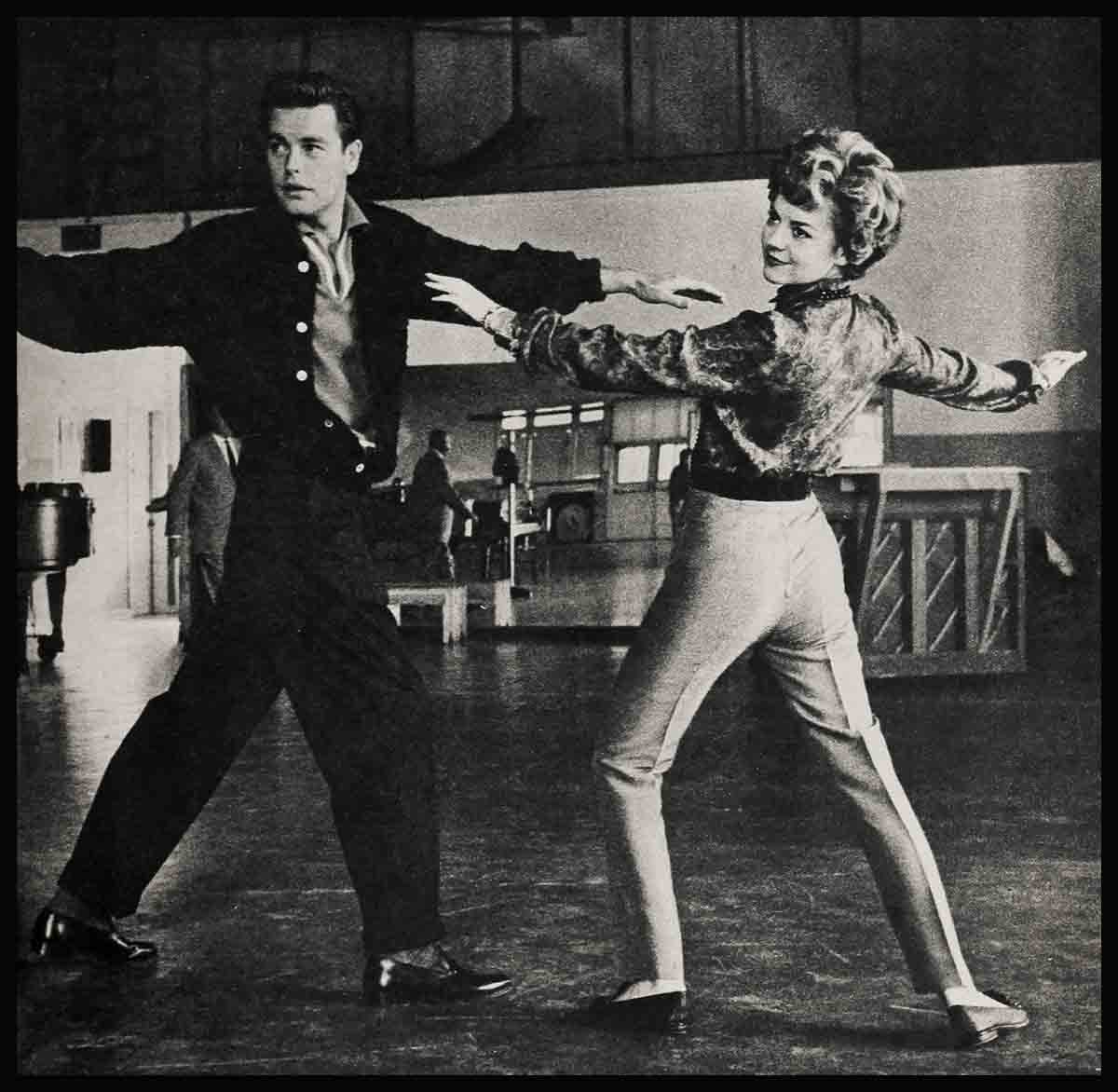

Jeff Chandler looks like a movie star, but try to convince him he is one. He thinks of himself as Ira Grossel—and that’s all. Gable’s a star. Crawford’s a star. But Jeff Chandler? As far as Ira’s concerned, Chandler doesn’t even exist! Take the time a group of stars went out on the Movietime, U.S.A. show. John Wayne was in the troupe and when he was introduced everyone cheered, Jeff right along with them. Then Jeff Chandler was introduced, and the cheers were almost as great. “I felt like the pretender to the throne. I felt the way the pretender must feel,” Jeff said. “It was thrilling to hear the people, but it was difficult to realize they were applauding me in the same way and for the same reasons I had applauded so many movie stars just a few years ago. And I kept thinking, “They just don’t know. They don’t understand. I don’t feel like a movie star.’ ”

There are lots of contradictions in Jeff Chandler. His eyes have the wise look of a man who’s lived forever, but he’s only 33. He looks as if: he’d flirt with every pretty babe, but during the seven months he was separated from his wife he was lonely and miserable. He gives off an air of sophistication, but when he meets a celebrity he’s almost speechless. There was the time, for instance, when he met Clark Gable. Gable had come to the Universal-International Studios to look over the work of a certain director. Afterwards, he lunched in the commissary with a studio executive. Jeff happened to come into the commissary and when he spotted Gable he couldn’t believe his eyes. He walked past the table three times to make sure. Finally, he said, “Well, won’t somebody introduce us?” Somebody finally did.

Gable stood up and shook hands. “Then he smiled at me,” Jeff said, remembering. “And that really did it. Then turning to the executive who introduced us, he said, ‘You sure grow em tall over here.’ ”

Jeff remembers every look, every word the great man said. This is not the way you’d expect a man who has the very same appeal as Gable to act. But that’s Jeff, and one of the keys to understanding him lies in his analytic, introspective mind. Don’t let the camera fool you, he’s much more than a handsome hunk of man, In fact, his being so ruggedly tall (six-feet-four) has been a sore spot for him.

“Height and bigness are associated with strength,” he says. “If a smaller guy picks on you and you don’t accept the challenge, you’re yellow. If you lick him, you’re a bully. If he licks you, you’re a schnook, And I’ve been taken by smaller guys, particularly when I was much younger and not so well coordinated.”

One Saturday night, when Jeff was in summer stock on Long Island, the company went to a restaurant for coffee. The guy who chose to pick on Jeff was of average height. He was also quite tight. He began taunting Jeff for being a “bum actor.” “He hadn’t even seen the show,” Jeff says, “so how did he know?” Jeff didn’t want to fight, he doesn’t like to, but he was talked into it. He leveled the guy and felt very sick.

The amazing thing about Jeff Chandler is that he began life with one desire—the desire to make the whole world love him. This is, he says, the reason for almost all of his mistakes. It is also why he is an actor.

Now he thinks he’s growing up emotionally. He’s learning that he can’t devote his life to making people like him. Some people will, some won’t. “When you try too hard for the love of your fellow man,” Jeff says, “you do ridiculous things. You spread yourself so far with emotion that you reach the point of frustration.”

Even though he realizes the truth of this, Jeff was devastated by something that happened recently. He was on location at Port Eustis, Virginia, for The Red Ball Express. You know about the demands of a location trip. Up at five-thirty A.M., back after sundown dead beat. So when the switchboard operators at his hotel advised him that calls were pouring in, he told them to use their own discretion about which ones to put through.

Well, one day a letter came to him at the hotel. It was from a girl who said had tried to call him. All she wanted was to hear his voice on the telephone. That was all. It was little enough, wasn’t it, since the letter said, “you mean more to me than anybody”? But she was told he was “too busy,” and now she was through with him.

Jeff wanted to call her at once, but her name was not in the telephone book. He wanted to write to her, but there was no return address on the note. It bothered him all during the making of the movie. It still bothers him, because, he said, “she may be losing faith in people. She mustn’t. For this reason Jeff answers his own fan mail as much as possible. “I’m way behind,” he says, “but I like to do it. I like to put my own stuff down on paper.”

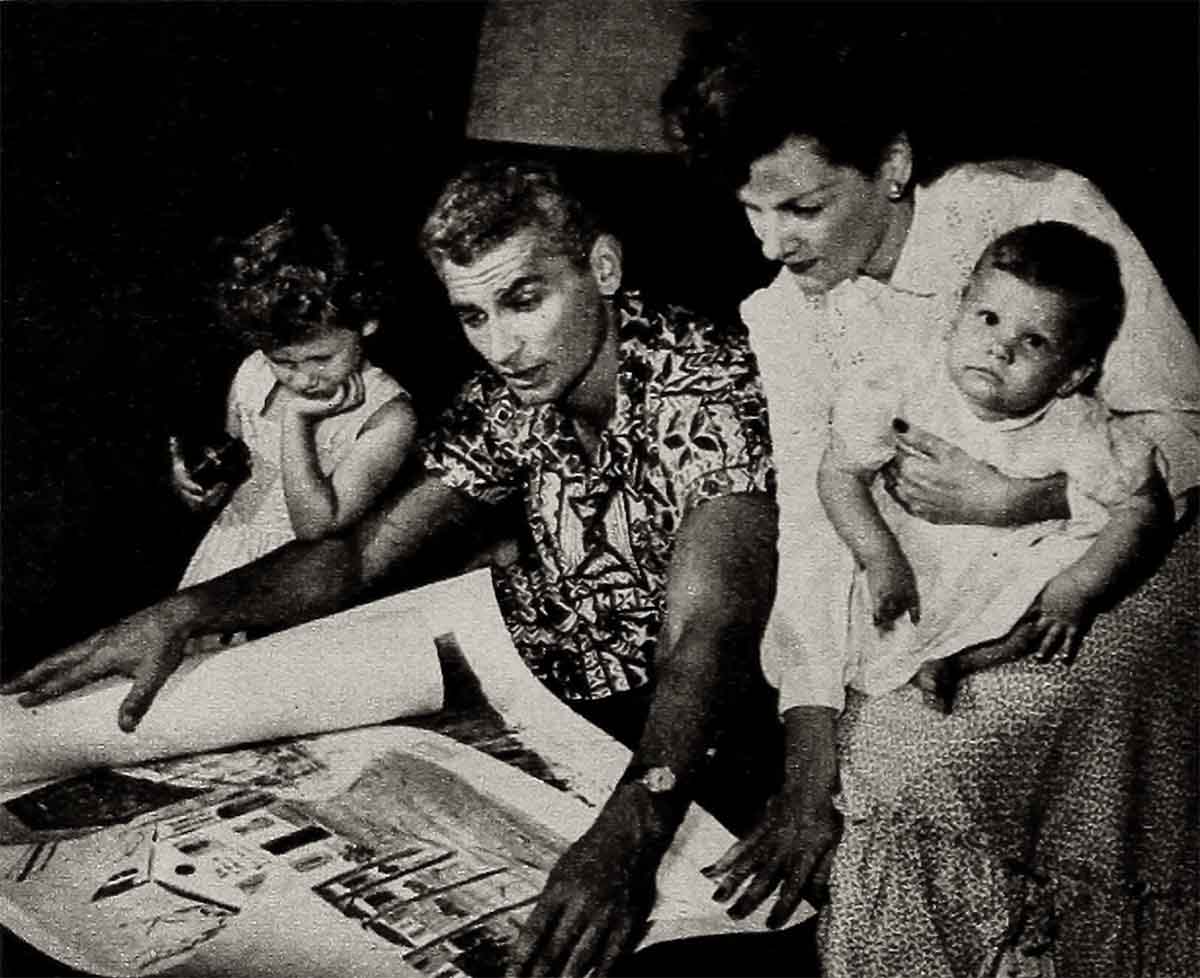

He’s the brooding kind, the thoughtful type who hurts easily and who doesn’t make a move without first thinking it through. Listen to the story of his separation from and his return to Marjorie Hoshelle, the girl he met in 1941. Jeff was appearing in stock at the time. She was in a neighboring company. Five years later, after he had done a four-year stint in the Army, he married her. She is the mother of his two daughters, Jamie, four, and Dana, two.

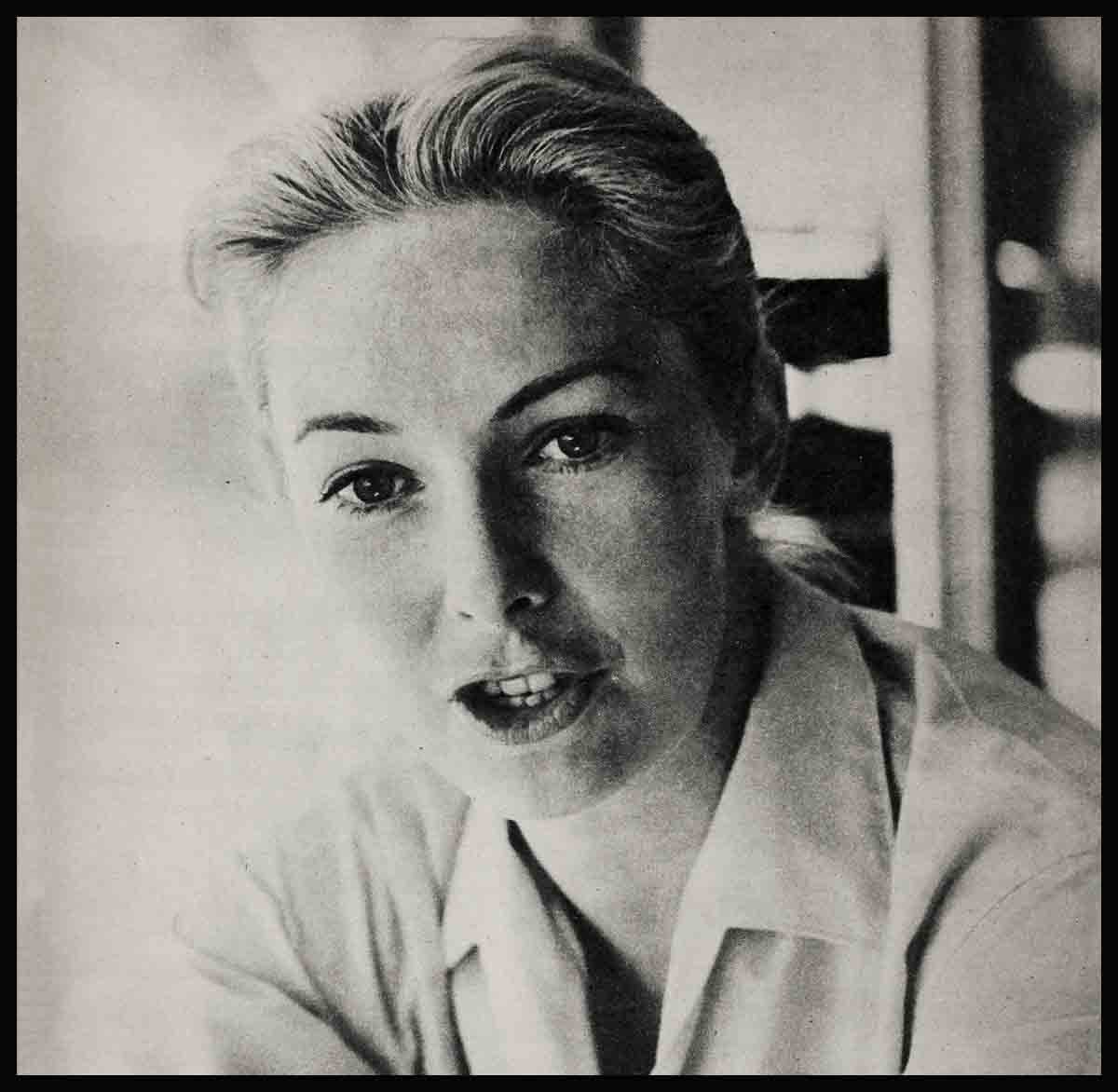

Marge is tall and good-looking, with skin like a baby’s. She is unaffected, “intelligent, exuberant. They seemed, as the song writers put it, meant for each other.

Everyone thought they were completely happy until the day a publicity girl at U. I went out on the set to see Jeff about an interview appointment. He was just sort of wandering around the set. The girl knew that Marge was in New York for a visit. “What do you hear from Marge?” she asked.

“Nothing,” Jeff said. “We’ve separated.”

The publicity girl forgot she would have to give the story to the press. She thought only how much she liked these two people. “I’m sorry,” she said. Then she added, “But don’t do anything hastily. If you’ve quarrelled or something . . . well, lots of people do . . . but wait a little while.”

“It wasn’t a quarrel,” Jeff said. “It’s been coming on a long time.”

What causes a separation that has been “coming on for a long time?” It’s nothing and it’s everything, it’s the Way two personalities blend or don’t blend.

Jeff underplays everything, always fearful of too much talk about a good thing. This isn’t Marge’s way. When Jeff was given the role of Cochise in Broken Arrow, he knew it might be the turning point of his career. It was a great establishing role. And for Jeff to have the part was Marge’s dream, too. Jeff came home and told her very matter-of-factly that he had the part.

“That’s marvelous!” she said, spilling over with delight. “What did the director say?”

“He said he thought I’d be good for the part,” Jeff told her.

Marge was disappointed. “Was that all?” And then, her enthusiasm returning, “Well, what did you say?”

“I said, ‘Thank you.’ ”

Now this is not a story you tell to the judge. This isn’t even one small ground for divorce. But it had to do with conflicting personalities, with Jeff’s subconscious guilt because he was an up-coming star and Marge was not. It had to do with Marge’s living vicariously through Jeff the career she might have had.

Jeff would come home at night from the studio, upset, maybe. He would sit, meditating, working out the problem. And Marge would ask, “Something wrong?”

“No. Nothing.” For Jeff must figure out the deal before he can talk about it.

“Is it anything I’ve done?”

“No.”

It all adds up day by day and the two people separate because they have placed a false interpretation upon the actions of the other.

They talked sensibly about the children. Would a divorce hurt them? Jeff was a child of divorce. So was Marge. What scars had his parents’ divorce left on Jeff? He tried to analyze it and “didn’t know for sure.” He knew that he wanted his children to “be as close to normal as possible. Whatever they really need I hope they’ll achieve.” He and Marge had tried to bring the children up “by the book.” But, Jeff said, “Marge and I are not qualified since we don’t know where the norm is.” He decided that a divorce would not hurt the children. It might change what they were or, rather, what they were to become, but it would not hurt them.

During the seven months Jeff and Marge were separated he saw her and the children often. He helped her move into a new house. And when it came time for the Academy Awards presentation he took her to the big event. He was advised against this. It would, his advisers said, only cause more newspaper comment. The questions would be asked, “Are they back together again?” “If not—why not?” And “What about Ann Sheridan?” But Jeff had been nominated Best Supporting Player for his work in Broken Arrow, and he could not, he said, take anybody but Marge. “She has shared so much with me,” he said. “This will mean so much to her—almost more to her than it does to me. I couldn’t take anyone else. I want to take her.”

Had you met Jeff Chandler during the time he was without Marge you would not have known him for the man he really is. This guy who loves people and wants people to love him dug a hole for himself and crawled in. He lived in his dressing room at the studio—and this was almost symbolic, for it was Jeff’s success.and the problems encumbent upon it that had come between them. And it was at the studio where he set out to solve his most vital personal problem.

When he needed companionship he sought the company of men. Men like to be with Jeff, they like to talk with him. Howard Duff, Tony Curtis, Gordon MacRae are but a few of his men friends. And then there was Ann Sheridan. In order to understand why she filled a gap in Jeff’s life you must understand Ann. She’s such a good Joe, ready with laughs, ready with sympathy when needed. She’s the kind of girl who talks man’s talk to a man. But, except for a few parties which he attended alone, he had no social life.

Jeff had to think it out alone. He had to, as he said, “Get a re-evaluation of everything in my life. It was a period of learning. I could have gone through with a divorce and found a kind of life and achieved a degree of happiness. There is no one direction a life has to go in. But then I began to analyze, to draw the line between need and want. There are many things we want. There are fewer things we need. And the things we need are harder to search out.”

And once he had worked this out, alone in a small dressing room in the big studio, he knew what his need was.

He and Marge went to Arrowhead Springs for a three-day celebration. There was something to celebrate. They were back together again. As they were driving toward the Springs Jeff started thinking about something that had happened. He started thinking out a business problem the way he used to before the separation. Marge grew silent, too. And Jeff realized he was doing it again. So he told her what was in his mind. And their getting together again was as simple as that.

Of Marge, Jeff says. “This is a great girl.”

There are those who say that the seven months changed Jeff. But that isn’t quite true. Actually, they only served to crystallize what he is. In those seven months he put his thoughts all together in one place.

Look into Jeffs eyes and you’ll learn a great deal about him. They are sad eyes yet there has been no great tragedy in his life. But he has experienced tragedy since he has the power of empathy. Empathy is, according to the dictionary, “imaginative projection of one’s own consciousness into another being.” All good actors use this when they are playing a role. But Jeff carries it away from the set with him into life so that he has experienced emotionally much that he has not experienced actually. It is this power that gives him his sympathy for, his understanding of, other human beings.

He has great intellectual curiosity. He says, “I hate the fact that I’m not going to be here forever to watch how everything comes out.” He is learning constantly and he wants to learn.

It is interesting to note that people who want to live forever, as Jeff does, do not require much sleep. Jeff does just fine on six hours. No matter how late he goes to bed he is up at seven because, he says, “there are so many things to do.” When he and a friend had their own stock company he slept almost not at all from Sunday until Wednesday. They would close a show on Sunday and start preparing for another which meant learning lines, rehearsing, constructing sets and painting scenery. If Jeff managed an hour in bed out of the 24 he was lucky. Marge likes to sleep and needs sleep. This doesn’t bother Jeff any more.

He used to have terrible dreams, but those awful nightmares were compensated for by the wonder of waking up. “It’s great to wake up from a bad dream,” he says. But the bad dreams do not come so often now, which is, of course, part of maturity and security. When his children occasionally cry out in the night he knows what they are experiencing. He knows their fear dreams are a part of every child’s insecurity.

Jeff has been doing research on maturity. Take, for example, his angers. He is annoyed with people who do not do a job as well as he thinks it can be done. And that includes anybody—even the children. When Jamie was two and first sat at the table with him and Marge, Jeff expected her to use her knife and fork as well as they did and not to spill anything. He was annoyed when she behaved like anything less than an adult. “But I’m better about that now,” Jeff says. “I have learned that she must learn and that I must not impose my adult ideas on her infant mind.”

His angers are sudden and explosive even though it takes a lot to get the big man mad. He used to smoulder until the moment his rage caught fire. But unless he could blow his top immediately in front of the person who had made him furious he did not blow his top at all. He could not carry the anger. The difference between then and now is that he does not smoulder. He laughs and admonishes himself, “Forget it.”

But the thing that still makes him wild is the person who tells him what he is thinking. “I know what I’m thinking and the other person doesn’t. I can’t take it when I say something and the other person says, “That isn’t what you mean at all.”

This really gentle man reacts so violently because this attitude has cost him friendships. (And remember, he’s the guy who wants the whole world to love him.) For example, he was talking once to an older friend of whom he was very fond. They were talking about acting. Jeff was trying to explain how he felt. The other man said, “You don’t mean that at all. This is how you feel.” And he told Jeff how he should feel.

Jeff was burning. “Don’t you tell me what I mean and what I don’t mean. Just because I’m younger doesn’t mean I don’t have a mind of my own. A mind of my own and a mind I know.” End of friendship. He is sorry about it, but that’s how he is and he cannot change. This antipathy is one of his few violences. Marge knows this and never tells him that he may be saying one thing and meaning another.

So much for his angers. His joys? A job well done—whether by himself or by someone else. And the well done job means not only his work on the screen but the job of living a good life. His greatest joy occurs when he has learned something or conquered a fault. The other day he was beaming, “I got real happy today,” he said. “The kids did everything I asked them to do not because I, the great big father, commanded, but because I asked them in an appetizing way.”

Then there is the case of his procrastination. He understands it and it goes a long way back. His mother was, he says, a “do-nower.” She did not nag him, but whatever had to be done had to be done at once. The boy over-reacted by rebellion. As a result if Marge says today, “You know, Jeff, you should fix that window,” it puts off the chore by a week. Or he used to. He is learning to control the rebellion. “I bring some humor to bear,” he says. “I remember she has asked me because the window needs fixing and not because she’s trying to drive me.” And this, by the way, is another thing Jeff got straight during the seven months of being alone.

It was for psychological reasons that Jeff wanted to be an actor. It was, he said, “a defense against voids. Maybe I was seeking the love I lost not being with my father when I was a boy. Ninety percent of all actors, I think, use their art as a substitution for something missed earlier.”

Success has given him confidence and security. “I’d be a big schnook if I didn’t have more confidence now,” he says. But success almost had a bad effect on him. “It’s a matter of leisure,” he explained. “You’ve got time to think. You have the freedom to think and sometimes that can be bad. When you’re not worrying about how to pay the rent you explore—looking for the things you want rather than the things you need. You lose sight of the real values and start believing you’re leading an unsatisfactory life.”

No, he is not a typical movie star, yet when he walked into the Universal commissary just after he was signed for Sword In The Desert, every woman in the place sat up and took notice. A studio executive recently summed up his appeal. “The women in the audience never feel they can mother Jeff. Women from eight to 80 realize he has sex appeal. But they never think of Jeff as ‘my boy.’ They think of him as ‘my guy’.”

You cannot mother Jeff because the core-of him is strong. Yet he is not predatory. He is not detached and cold. He is not, actually, sophisticated. He has an inner warmth. He likes more than he dislikes. His and Marge’s idea of a good time is to visit and be visited by friends. Lots of friends. He is not in any sense “on the make.” He doesn’t have to be.

His face belies his character but his voice does not. Listen to the voice and you’ll know him. His voice is full of pity and sympathy for mankind. That’s Jeff Chandler. It’s nice to know he does exist.

THE END

—BY KATHERINE ALBERT

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MARCH 1952

No Comments