What’s Happened To Hollywood Night Life?

One night a few years ago in a Hollywood establishment known then and now as Mocambo, a girl of mysterious identity and origin went over to Errol Flynn and broke a coddled egg on his head.

The incident churned: up a few local headlines but did not excite anyone unduly. This was in an era when the una steady graph of what is called “Hollywood night life” was on one of its periodic climbs toward delirium, and in fact, not to break coddled eggs on stars’ heads was considered effete. Actually the incident passed off rather well, occasioning no discomfort to anyone save Mr. Flynn, who underwent the shock you would expect of a man who has no deadly aversion to eggs taken externally but who hadn’t happened to order a shampoo.

The red-haired girl had not known Mr. Flynn nor he her. She went over to his table and asked if he were Errol Flynn. No perjurer, Flynn said he was. The Errol Flynn? the girl asked. Mr. Flynn didn’t simper. He just said yup. Squooosh.

Mocambo was loaded with filmdom’s hot rocks that evening. They laughed appreciatively and resumed the somewhat intense business of roistering in the public eye. A few paid tribute to Flynn’s acumen in hiring an egg-plopper all his own, and a few others decided the caper was an authentic one, raising the charitable grounds that Flynn’s coiffure and a coddled egg were natural affinities. Ham, that is, was mentioned. but in no more vicious a spirit than a baby cobra might exhibit if stepped on. The girl was hauled away before she could apply pepper and salt and life went on.

Well, that was a normal Hollywood night life item yesterday. Tomorrow it may well be normal again. Today it is simply nostalgic and a little quaint, like a Duesenberg phaeton or a raccoon coat. Today, if truth must be told, Hollywood night life is decorous and becalmed, biding its time, perhaps, like General Grant at Galena, waiting for someone to come along and open up with the seltzer bottle again. Today Hollywood night life, while by no means in doldrums, is like—oh like this:

The same Mocambo was pretty well jammed on a Friday night a few weeks ago. At nine P.M. there had been only four customers in the place but at eleven a deep breath was ill-advised. The green parakeets in their glass cage overhanging the south wall were in moderate frenzy, and the eyes of Texas were bulging in their search for famed identities. The eyes of Texas are extremely welcome in Mocambo these days, and in Ciro’s as well, Ciro’s being the other first-line Hollywood night club. Texans are about the only people the tariff doesn’t seem to bother. Anyway, after a while, the Dallas table spotted a party that looked so familiar everybody figured “movie stars” and sat back happy. At the same time, the other party spotted the Dallas table and came to the same conclusion. A half hour of mutual ogling ensued before the dismal truth became evident. The two parties lived a block from one another in Dallas and frequently exchanged nods at the neighborhood supermarket. Their mutual disappointment was so violent that they all got up and went to Las Vegas on the next plane.

As a waiter observed dolefully, it never woulda happened when Lupe was around.

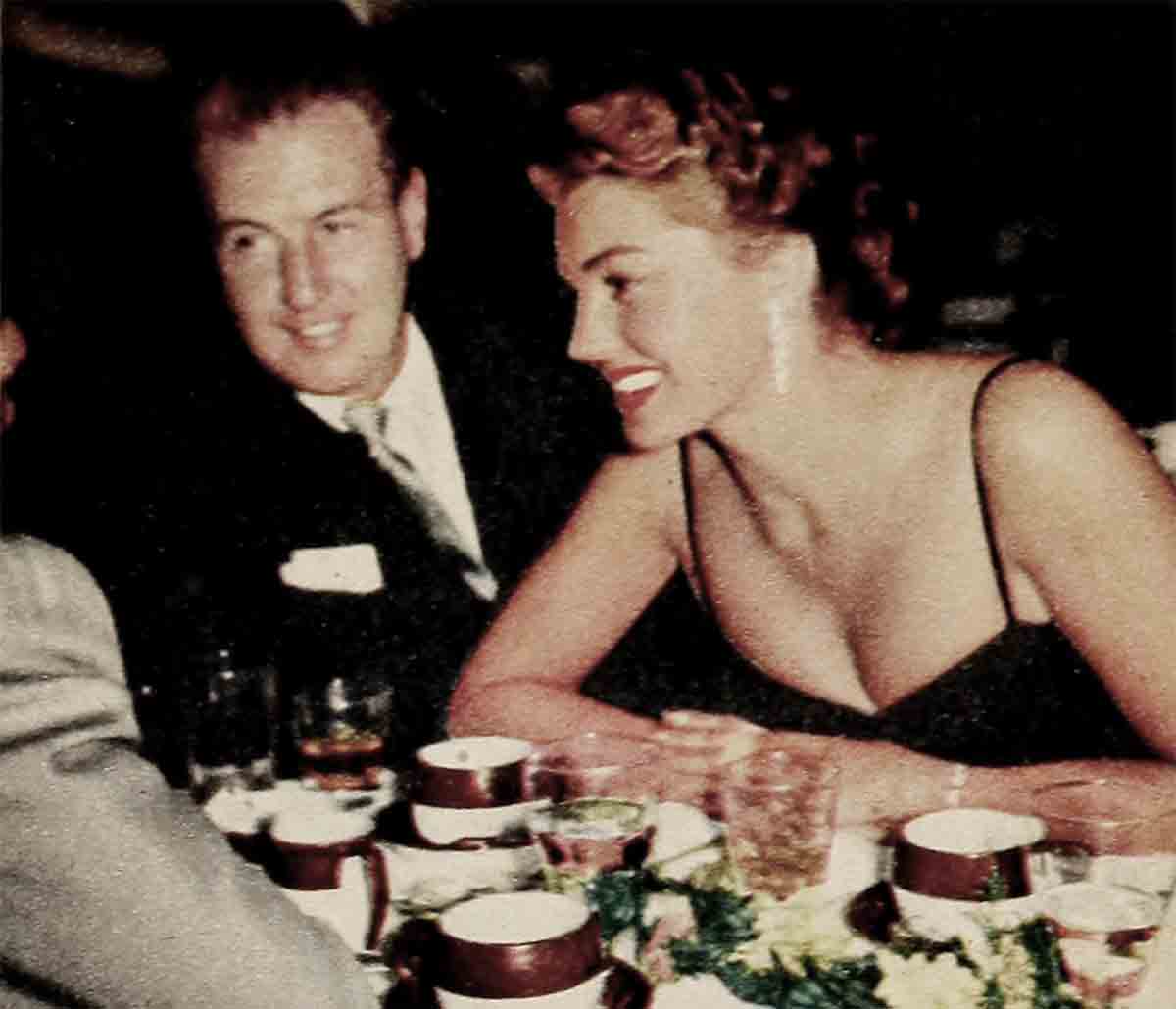

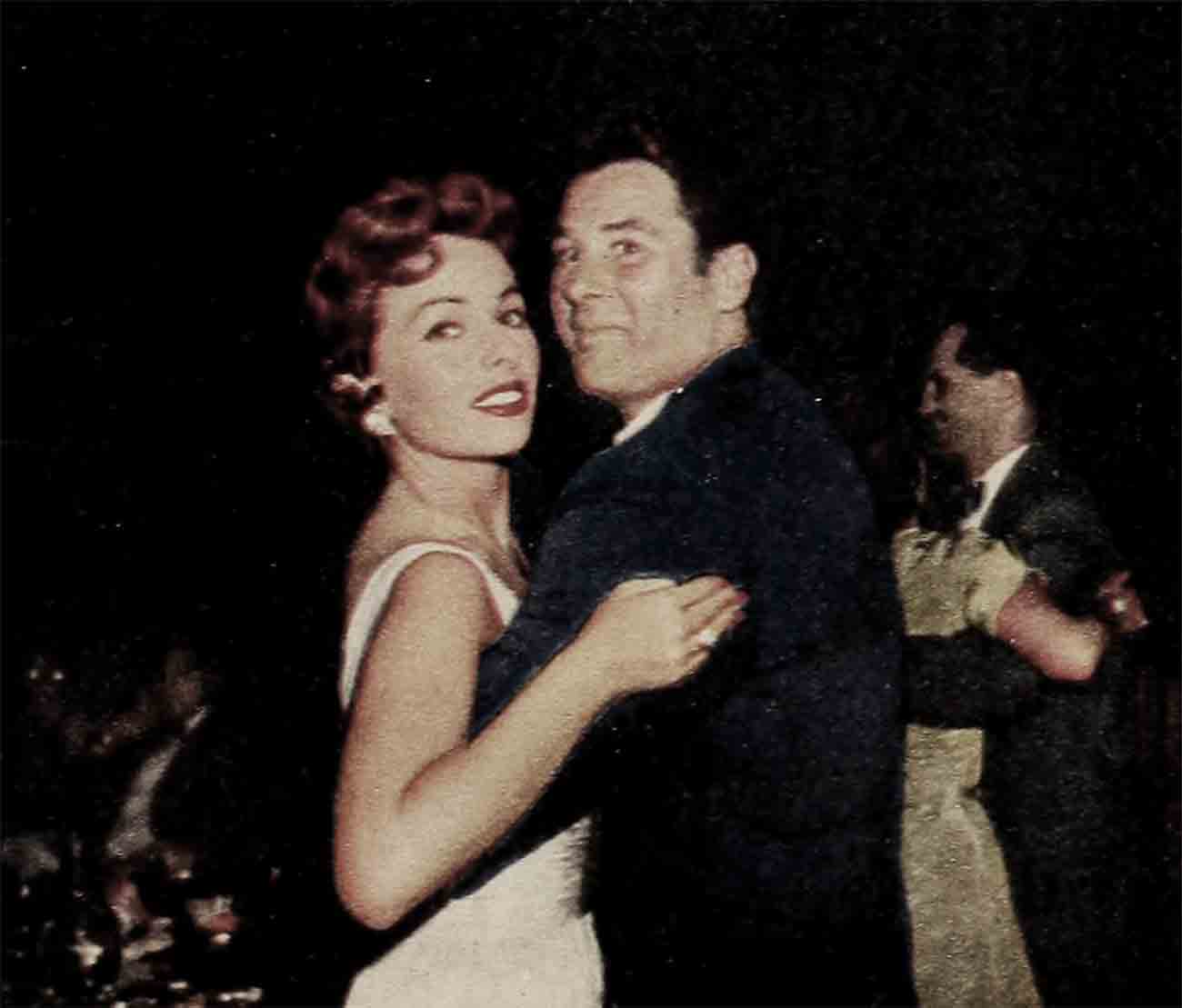

Actually things weren’t so bad as all that. There were two stars of unquestioned rank in Mocambo that night, and stars that don’t get out much any more, too. They were the Dick Powells, half of whom is June Allyson, and they were feeling frisky enough at one point to dance with their arms around one another and kick their heels. There was a Los Angeles disc jockey and with him a girl who had played a striking bit in a Metro film and now was being, as the deathless phrase has it, groomed for stardom. There was a short agent with a tall blonde whose mink coat the agent would take back at the end of the evening because it belonged to him, not to her. And when these two danced, the agent, who had to steer the couple, looked like an engineer sticking his head out of the cab. There was another agent with the divorced wife of a producer, and three tables away the producer with an unknown redhead, maybe the one who bopped Flynn, and a table away from them a Houston playboy who had had his name misspelled in four columns that week. As a matter of fact, the trade papers and columns two days hence would report all sorts of undercurrents and intrigue going on under Mocambo’s roof that night, but none was apparent to the eyes of Texas nor to any other lay eye. Subtlety of so private a stripe does not nudge the turnstiles on the tourists’ side of the tent.

Yet, the question posed by the title of this essay is in a way invidious. It’s loaded, for instance, clearly implying that Hollywood night life is dead in its harness, and that is not so. It is, let us say, only suffering temporary anemia because star names and publicity are its life blood, and one cannot be legitimately sustained without the other.

Then again, the query can be answered in another way—and it has been. Nothing has happened to Hollywood night life. It goes on as before. Only now it takes place in Las Vegas.

Las Vegas is indeed, by remarkably well informed accounts, the primary villain of the piece.

“I give you,” said a famed Hollywood Boniface the other day, “two words: Las Vegas. That answers your question. I run a night club here, I shouldn’t be this honest. But why kid ourselves? Mocambo, Ciro’s, the Cocoanut Grove, we all ask a two dollar couvert. We have to. But Vegas with its gambling? You can see a twenty thousand dollar show there for the price of a beer. Have you checked on Vegas this week? Here’s who you can see. Red Skelton. Betty Hutton. Milton Berle. Tony Martin. Only a few blocks apart. I’ll give you salary figures. Betty’s drawing $20,000 a week, Berle $25,000. Tony’ll come in around $15,000 and Skelton—get this now—$32,500! I’m told Dietrich’ll get fifty when she plays there! Non-gambling establishments can’t pay that money. And if we could, the acts still play Vegas first. Then there’s another thing. Vegas is between here and the East. Tourists on their way to Hollywood stop over there for a drink and a try at the tables. Two weeks go by and they’re still there. Broke or flush, beat or healthy, they then turn around and go home again.

“That’s the big item. Another is general economic conditions. This industry’s divided and nervous and the old plush days are over. For the time being, anyway. The stars stay home. They do their partying there. The younger players are being forbidden by their studios to go to night clubs. That doesn’t help us. Don’t use my name now. I shouldn’t be this honest. I should be like—” he mentioned a prominent rival, “—and tell you everything’s great. But I can’t. Finally, we get around to’ Vegas again. A star does have a week-end off, a few days to play, he heads for there. Less than three hundred miles from here, five hours’ hard driving, and no restraints at all. You’ve asked me, I’ve told you.”

But there was something this spokesman hadn’t mentioned. Decorum. It is practiced in Hollywood night clubs these days. Rarely any more are jaws swung at or hair pulled. This is laudable. But there are few night club impresarios who do not know that uninhibited behavior is good for business. In quiet corners, they applaud the exhibitionism and fracases they deplore for the press. Once the owner of a place on the Sunset Strip sat and watched an argument between a second-rate actress and a Pasadena post-debutante come to an ugly boil. He was frankly interested, noting the presence at ringside of two columnists. When his staff showed symptoms of intervening, he waved them down. “Let ’em fight,” he said. “We’ve lost money long enough.”

Whether or not his psychology was correct is debatable. But certainly it is so that few Hollywood habitués can speak of the good old days of its night life—pre-war to a great extent—without choking back a tear or, in even less grammatical circles, winking back a lump in the throat.

There was the vivid, tragic, Mexican star who spent that night of undiluted gaiety in Mocambo, a white ermine coat over her shoulders, a super-big hello for everyone. As she left, she encountered a writer friend. “Tell me, beega boy!”, she called. “Am I a bad girl?” She shook a finger without letting him speak. “You bedda not say yes!” The writer said instead: “See you tomorrow.” The two had a tentative interview date. “Mebbe you see me,” said the star. “Mebbe I dawn’t see you. I dawn’t knew.” She turned and surveyed the whole room lovingly. “G’bye,” she called. “G’bye, now!” The next morning Lupe Velez chose to take her own life by the sleeping pill route. Perhaps she had chosen before that night. Her gaiety had had none of the constraints of indecision. It is anybody’s guess. But there was a memorable swatch of Hollywood night life history.

In happier, more tempestuous days, the same Miss Velez had once tapped an obstreperous wolf briskly across the pate with a champagne bottle, then leaped on a table and challenged anyone in the room. Just carried away, that was all.

The belligerent spirit apparently is more readily evoked by the atmosphere of Ciro’s, elegant counterpart a few blocks east on the Strip and across the street, although old hands are inclined to regard Ciro’s fisticuffs as strictly prelims. “The main eventers,” one has said, “wait for Mocambo. Not so many stairs to fall down in case they trip.”

Frank Sinatra and New York columnist Lee Mortimer did not wait. At the top of the stairs leading down to Ciro’s old parking ramp, they had at it, with superficial wounds to Mortimer’s frame and a much deeper incision in Sinatra’s bank account, after he’d settled the damages out of court. Nat Dallinger, the veteran photographer of Hollywood night life who pulled the combatants apart, has remembered the details well. “It never would have happened,” he has said, “if it weren’t for a couple of Frankie’s so-called friends. They egged him on. I might have got the picture of the year if I hadn’t decided to be peacemaker instead. But Mortimer could have been really hurt. He’d been down twice, and there was broken glass on those steps that night. That wasn’t funny.”

It was at Mocambo, on the other hand, that in the heyday of the era, the punch of the decade was landed, one girl’s uppercut catching the chin of another with such unswerving precision that the recipient was knocked clean out of her shoes.

And it was at Mocambo that Victor Mature, frolicking a bit after many arduous and perilous months with the Coast Guard on the Murmansk run in wartime, entered the gents’ room and straightway ran into a civilian heckler who accused him of fighting the war in a night club. Mature is no professional hero but was forced this time to point to his ribbons as evidence that this was just a stopover. The heckler persisted. And since he was actually as big as Mature himself, Mature decided he was entitled to act. “Keep it up,” he told the menace, “and I’ll dunk you in this washbowl, even though I filled it for another purpose.” The man kept it up. He will never have his head under water so long again; not without drowning.

Virginia Hill, good friend of gangland’s late Benjamin (Bugsy) Siegel, is not around any more, either. She got mad at the Government. Estimates of her are varied and have no special place in this account, but no Hollywood night life Bucko has denied her color and headlong generosity. An old friend has said: “She thought money was for only one thing—to make people happy.” So Virginia, when night-hood was in flower on the Strip, made people happy. On each evening of wassail, she fared forth with ten one-hundred dollar bills in the bottom of her jewel case. These she distributed as tips among hat-check girls, powder room attendants, waiters, parking lot attendants, bus boys, photographers or simply people whose looks she liked. One night she entered a night club past a group of the awed little people who stand with cameras and autograph albums outside the Strip’s swankier spots. She wore a full-length mink of sufficient pictorial impact to draw an anguished sigh from one of these, a young girl in rather shabby straits. “You ever see anything more beautiful?” the girl managed finally. Miss Hill, who later was to confound the Kefauver Committee with her ignorance of the tax structure, stopped in her tracks. “You like my coat?” she ahead her unknown admirer. “You got my coat.” And she threw it to her.

Another time, by word of an eye witness, Miss Hill became sated with a Russian sable number. Arrived at Ciro’s, she first dropped it on the floor, then kicked it pettishly under a table. A waiter hurried over and retrieved it. “Yours, madame?” he asked. “Yeah,” snapped Miss H. “Take it. Lose it. Don’t come back with it.”

But even this, our fun-loving heroine was able to top. Hearing one night that the wife of a close friend of hers in the night club press had only a few hours past given birth to a son, she approached her pal, the proud father, for confirmation. He grinningly confided it was so, barely stopping himself from offering her a cigar. “Well, now,” said Miss Hill. Next day the infant received a token from Miss Hill, a little gift to get it started off okay. Five thousand dollars in war bonds. The Hollywood night club atmosphere in those days plainly had a quality all its own.

A career or two has been made in Strip environs, or at least boosted along. Lana Turner, a one-time night club regular who doesn’t bother so much any more, has been instrumental in several. A guy named Joe in Mocambo or Ciro’s is a guy named Joe and nothing more. But if he happened to be Miss Turner’s escort, they took the trouble to find out how it was spelled. And Miss Turner, a good-hearted girl, was glad to provide this information, hold still for pictures, or even lend the columnists a pencil. This sort of cooperation did not exactly poison the career leanings of Turhan Beys or Stephen Cranes.

But the switch didn’t occur till later. A time came when starlets were in season and many of them bedecked Mocambo nightly, letting the breeze blow them across the range of whatever producers were present. Outside, meanwhile, a young man was too busy hustling arriving and departing Cadillacs to get his profile into a strong light. He worked there, but strictly. Nonetheless, he was observed one fine evening, and by and by, while the starlets returned to their own particular underbrush, he put away his jumper and got to be known here and there as Champ Butler.

The good, the stimulating, the pugnacious old days of the Hollywood neon scene—may they come again and soon, with their Band-aids, thousand dollar bills, jeroboams of champagne, baked Alaska, and flying butterballs and breadsticks. While Errol Flynn was the busiest light heavyweight in the circuit, the most willing of the welter contenders was Humphrey Bogart, once faulted by a friend on the single flaw: “When he’s had a couple of belts, he thinks he is Humphrey Bogart.”

Like Flynn, Bogart was the victim in most cases of objectionable strangers, bums who tried to chivvy him into fights merely in the hope of a little stray publicity for themselves. Bogart, however, was not averse to playing ball with them, with the result that one fine day he found himself barred from just about every deadfall in the block.

So he stayed home—or confined himself to the saloons he professes to like better than night clubs anyway. But there came a certain time and a visit from an out-of-town friend who wanted to tour the brightest places. Bogart confessed his plight sadly. “I’ve reformed,” he told the friend, “but who’ll believe me?” The friend bristled righteously in Bogart’s defense, and together they set out. Club after club rejected Bogart, who stood meekly in the background, but finally they found one whose manager was willing in a qualified sort of way to relent. Bogie, the friend said, was waiting out on the sidewalk, thoroughly chastened. He was a changed man now and wished only to drink a glass or two of lemonade in an obscure corner and look on wistfully while others enjoyed the fun that was denied him. At this, the manager burst into tears and cried: “Go get him! The fatted calf’s not on the regular menu but I’ll have the chef run it up!” And the friend went out to get Bogie—who was rolling around the walk in fierce combat with a sprocket salesman from central Michigan.

Bogart lived dangerously in other ways during the salad days of Hollywood’s public merriment. One early morning, he and a producer friend returned from an extensive junket up and down the Strip, having decided to adjourn to the producer’s home after Bogart had swung at a fellow-actor and missed him by 30 feet, or precisely the distance the actor was away from him. Home again in a manner of speaking, Bogart felt disposed to curl up in the producer’s fireplace and get a little shuteye. This was all right with the producer but he felt Bogart’s tie should be loosened, and got to work on the project. Bogart tried several times in a patient way to tell his friend that he was tightening rather than loosening the knot, but could not make himself any clearer than “Uk,” and was registering straight magenta when the producer’s wife intervened.

But on a third occasion, Bogart emerged triumphant. He was entertaining a visiting interviewer at Ciro’s when, with stunning unexpectedness, the visitor went to sleep. He slept for two unbroken hours while Ciro’s ebbed, flowed and bellowed. Finally he awoke and the two left. Bogart thought nothing of the incident until the next morning, when he had the invigorating realization that the writer doubtless would remember nothing of what had happened during his siesta. Immediately he called the man on the phone. There was nothing to worry about, Bogart began stoutly. Bogart would stand by in the event of any crisis. Wh-what crisis, croaked the poor writer, groping for his mental hinges. Oh, nothing, really, Bogart purred reassuringly. Of course, the clam juice down the woman’s back might have seemed odd in some places but this, after all, was Hollywood. The writer groaned and shuddered. Naturally, Bogart went on, it might have been a wee mite better if the writer hadn’t brought down the comedian with a flying tackle in the middle of the floor show, but the comic was a tolerant fellow and would understand. Furthermore, Bogart concluded, his friend should not worry a bit over having to be carried out in full view of a packed house. Happened every night in the year.

The writer was on his way to join the Foreign Legion before Bogart decided to pull the knife out.

So goes it no longer. Bogie stays home these days, or goes to Europe or whatever he does. Sonny Tufts, on whose blithe record is informal conducting of orchestras and turning flips down trolley tracks, is nowhere to be seen. Joan Crawford, too, has gone to ground, and when Tom Neal had at Franchot Tone over love of Barbara Peyton, it was in comparative private.

The youngsters turn up from time to time. Mitzi Gaynor is about the most regular and a godsend to the photographers, who have a habit at present of showing up but leaving their cameras in the car. Jane Wyman and her bandleader husband, Freddy Karger, are on hand now and then, and Ginger Rogers and her husband, Jacques Bergerac, if they happen to be in town. Betty Grable you might see, with or without Harry James, who spends a lot of time on the road, but if she’s not with him, she’s with Betty and Harry Ritz. Terry Moore. Corinne Calvet and John Bromfield. A handful of others.

Not long ago, Joan Caulfield made the casual observation: “If you want to write a story about Hollywood night life, go from home to home, where it’s really taking place. All the little cliques, you know. Who goes out?”

Not even Marilyn Monroe, who showed promise at first, has saved the day. She stays home now, too.

A few traditions are maintained. If a married or dating couple really want to have a knockdown, dragout, yowling fight, they save it till they reach a night club and the undivided attention of press and public. There’s no sense throwing a natural like that away.

Likewise, almost any event smacking in some devious way of “charity” still flushes a fair quota of big names. Let a regulation eat-and-guzzle promise to devote 20 per cent of the take to the Society for the Prevention of Throwing Firecrackers Down Crocodiles’ Throats, and it’ll get a notable turnout of the old, familiar faces.

But whereas the Flynn omelette of another time was a thing of no more than passing interest, the big scuttlebutt among the press a few months ago was a paler incident by far: the reluctant agreement of Gene Nelson to pose with Jane Powell two days before Miss Powell and husband Geary Steffen announced their breakup. Nelson’s consent rather affronted a number of folk who back in the days of Lupe and Virginia, Bogart and Flynn, Clara Bow or Jean Harlow or Paulette Goddard—would have been affronted by nothing fee ben a poke in the eye with a sharp stick.

In yet another sense, the saga of Hollywood night life makes its own minor contribution to contemporary history. In January of 1949, for example, this magazine ran a story by-lined by Charlie Morrison, Mocambo’s owner. It featured pictures made at the night club of couples presumably enmeshed at the time in various stages of amour. Less than five years ago, they were Diana Lynn and Bob Neal, “a steady Mocambo duo before her engagement to architect John Lindsay”—now divorced from Diana Lynn. They were Shirley Temple and John Agar, husband and wife, holding hands; “Errol and Nora Flynn” (remember?); Clark Gable with Nancy (Slim) Hawks. Quaint, as previously remarked, like the ’coon and the Duesenberg.

Or way, way back, when Saturday or Sunday nights were the big Sunset Strip deal, here by recollection of photographer Dallinger was a favorite group table, these an inseparable lot: Claudette Colbert and Dr. Joel Preston, her husband, whose marital status is said to be shaky now; Gary and Rocky Cooper, whose m.s. definitely is shaky; the Fred MacMurrays—the beautiful Mrs. MacMurray died earlier this year after a long and tragic illness; the Robert Taylors, when Mrs. Taylor was—and is again—Barbara Stanwyck; the Henry Fondas—Mrs. Fonda is dead by her own hand; last and most happily, the Ray Millands and the Jack Bennys, still live, together and content.

In Hollywood night life, history is a matter of which edition you read. And this phase, while reasonably stable and prosperous, is not the full and lusty, nor lustrous, thing that its predecessors made of themselves. Carole Lombard is gone—and there are no echoes of dead laughter because dead laughter has no echoes.

Cycle is inevitable. The “good old days” will come again. Lana will be back from Europe, Rita’s in circulation, all is by no means lost. While glamor takes a break, stability and decorum will have to stand in for it. Some Hollywoodians applaud the change. But most are saddened.

THE END

—BY STEVE CRONIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1953