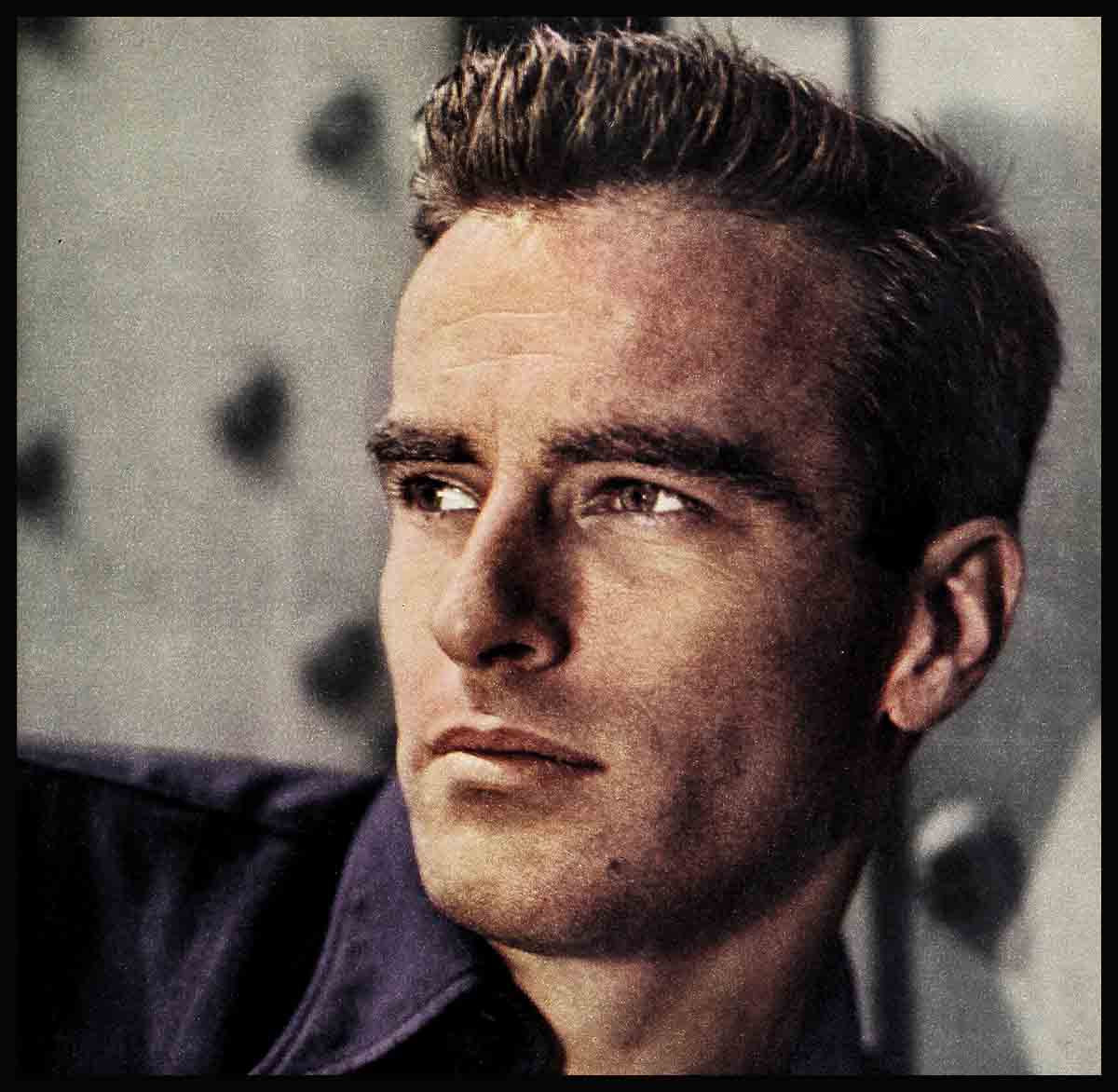

Montgomery Clift’s Tragic Love Story

The love story of Montgomery Clift and a girl whom we will call Mary could have walked right out of the pages of some of the world’s most romantic fiction. The story would have begun with the recounting of the life of Monty, a boy who through his own efforts rose to fame and fortune. It would have told of his meeting with bubbling, vivacious, beautiful Mary, the daughter of a wealthy executive whose family money had provided her with everything she had wanted.

In the beginning, there was a magnetism of opposites attracting. Monty was the stiff-necked independent boy, dedicated to his art, free of entanglements, of family ties of any sort. Mary was a girl whose family framed her every action with love. Confident of their affection, she was outgoing, generous in her fondness of people. She had the warmth, the sincerity that comes from complete knowledge that nothing could ever really harm her.

Through their association runs the thread of change—a change that was to come to Monty, to his sensitivity to people, to his outlook on life. And their final decision—it revealed a nobility of purpose of which few young people can boast today.

In Hollywood, when Monty first arrived, he was a recluse, the oddity. But this was no new role for Monty. His stiff-necked independence marked him, even in his early days at school. His classroom hours held little appeal for him, for even as a child, the stage intrigued him. His parents were his first audience, a kind and sympathetic audience.

His father, a stockbroker who took up residence in New York after moving from Omaha where Monty was born, sympathetically allowed his son to follow his own dictates. When the family wintered in Florida, Monty was given his first opportunity to expand his talents when he appeared with the Sarasota Players. Meanwhile, his brother and sister went their more conventional way. “I had a mess of education,” Monty says now as a simple statement of fact. “When I want to know something, I ask my brother who is a Harvard man or my twin sister who was graduated from Bryn Mawr.”

Only once did Monty, in those early years (actually from the trusting age of 14), allow his family influence to get him what he wanted. He arrived from Florida on Broadway with letters from family and friends to a Broadway producer. As a result in 1934 he was cast as one of the youngsters bedevilling Thomas Mitchell in “Fly Away Home.”

Shortly he became what one critic called, “That rare creature, a child actor who made good.”

In reality, he had only a brief period to luxuriate in the designation “child actor,” for already he was tall and talented and as the years and times became more serious, so did his roles.

He carried the brand of Cain, the first murderer, in “Skin of Our Teeth.” He was the perplexed George Gibbs in “Our Town.” In Lunt and Fontanne’s production of “There Shall Be No Night,” he was the young Finnish soldier who goes out to certain death.

Directors say, “Montgomery Clift doesn’t play a character, he is the character.”

Inevitably the weight of the tragedy he carried to the footlights penetrated into his own consciousness. His health broke and he regained his strength only by deserting Broadway and going out to do manual labor on a friend’s ranch.

But peace of mind remained elusive. Returning to New York, he became a key member of a group of serious young actors who asked more of the theatre than the applause of enraptured playgoers.

Essentially, they were looking for a standard of values and a way of life, not merely a way to make a living. They found reading more stimulating than adulation. discussion more exciting than night clubs.

The stacks of books and records in Montgomery Cilft’s apartment multiplied while his wardrobe dwindled. By the time Paramount director Howard Hawks discovered him in a short-run Tennessee Williams play and signed him for Hollywood, he was subject to those two-necktie stories which later irked him.

Despite his subsequent protestations that he always had whatever clothes he needed, there are those who still assert that he came to Hollywood with three shirts—one dress shirt which was always either on his back or at the laundry, and a couple of sports shirts, the no-ironing kind, which he rinsed out in the wash basin in his one-room apartment.

Hollywood swiftly discovered that this handsome young man, who by birth, background and stage success rated an invitation from the best of social circles, much preferred his own company and that of a few long-time friends. Seeing his name in gossip columns meant nothing to him. Neither did he place any importance in being seen with the right people. He made it clear that his time off set belonged to him.

And before very long he had plenty of it, for he was having difficulty over pictures. He credited Elia Kazan with giving him the advice, “Take only those parts you can do with integrity. Then success will come of its own accord.”

Acting on it, Montgomery Clift turned down roles which would have fattened his funds but bankrupted his pride. Before he appeared in “Red River,” he was thirteen hundred dollars in debt. His next three pictures paid him one hundred thousand dollars each, but the habit of austerity stayed with him.

He made no secret of the fact that to escort Elizabeth Taylor to the premiere of “The Heiress” he had to rent a dinner jacket. He owned none of his own.

Notably, however, he made one impassioned foray into Hollywood society, but even that was done on his own terms.

After “The Search,” a story about displaced children, filmed in Europe, he appeared, under sponsorship of The Organization For Rehabilitation Through Training, at a party attended by several hundred wives of executives, writers, directors and producers to plead for help for needy youngsters in distressed areas. He spoke movingly, drawing on what he had seen during the making of his picture. When the cause was important to him, Montgomery Clift was ready to prove he was no recluse.

But on the subject of girls, Monty remained skittish with interviewers. Most frequently seen with him was one whom a reporter called, “a vague sort of mystery woman, always in the background.”

Questioned about her, Clift took pains to explain, “No, we’re not engaged, we’re not in love, we don’t intend to marry She’s simply a dear friend I’ve known for ten years. I’ve got to rehearse my roles with some one—I can’t just go on a set cold—so I rehearse them with her.” Then he added, “I want to make it clear there is no romance involved. If I’m seen out on a date with another girl, I don’t want it to seem as though I’m running around.”

What the woman in question thought about their relationship remains in the realm of vagueness and mystery. When asked about it recently, she refused comment with the statement, “That is private. I would rather not answer even one question because I would not know what kind of jungle I was getting into.”

Customarily, however, Monty diverted questions about rumored romances by speaking, instead, of his work. There was a forecast of his own ultimate fate in his statement, “Mainly, I want to be responsible for what I do. If it is something good, I can take pride. If it isn’t, I know it was my choice alone. You’ve got to be in position to risk your professional neck every six months. The important thing is to be in position to risk it.”

There is indication that throughout his career Montgomery Clift has keenly realized that for every artist a conflict inevitably arises when his human need for love and companionship clashes with his consuming drive to attain perfection in his chosen field.

For the true artist must, first of all, put that desire for perfection ahead of all other interests in life. He must, in Clift’s own words, “Be free to risk his professional neck every six months.” The dedicated man will risk everything to maintain such freedom.

Yet, for all his dedication, he cannot escape being human.

He arrives, therefore, during the natural course of his development at the point where anonymous praise from audiences is not enough. He seeks also the affection and approval of that one person whom he, himself, holds in the highest regard.

Only with that person does he find the communication of shared experience. With that person, too, he is able to let down—to find release from the tension which everlastingly drives him toward new achievements.

But here a new conflict develops and intensifies:. He now has two fears. He is afraid to relax the tension, for without, he may not be able to do the creative work to which he had dedicated his life. He also is afraid to become so devoted to a single person that the loved one’s welfare may become more important to him than his own freedom.

Montgomery Clift, who has studied the history of all arts, could not fail to be aware of this bitter choice. Music, painting, acting, writing, all have their notable examples of great men who, through love, have sacrificed either their careers or the women who inspired them.

Until Mary came along, Montgomery Clift had been able to postpone this crisis “No entanglements” was his motto.

But in Mary, he encountered a girl who by background, training and her own feminine instinct regarded love not as an entanglement but as a fulfillment and a way of life.

For here was no mere pampering heiress, no soiled darling beset by the notion the world owed her praise.

Instead, she has a family history in which men have depended on their wives for encouragement and help during stress and in which women have given both their work and their love to aid their men in reaching their goal. Her family has a history of big risks, big rewards, and above all, hard work and sacrifice.

The tradition of hard work has been carried down to Mary. In her training, responsibility has been emphasized over privilege. She has been coached in the old-fashioned manner to carry out her personal projects without any publicity.

Mary, too, had an ambition—but not the kind that Monty has. More than anything, she wanted to sing. Realistically, she realized her limitations as a performer. And although her father has influence in Hollywood she never used him to further her career.

Her own aspiration heightened her appreciation of Montgomery Clift’s talent when they met and her own bubbly happiness made the deepest impression on him.

He could have been expected to dislike her on sight, because here was a girl who was the epitome of Hollywood Society (with a capital S) which he shunned. But who can resist a pretty—and trusting—young girl? A young girl who says with contagious enthusiasm as though she had never heard of such a thing as a recluse. “Oh, Monty, we’re having a party. You will come, won’t you?”

Certainly not Montgomery Clift, for when he likes a person, he responds instantly. Friends say, “You can see it happen. It’s as if some one turned on a light.”

Following Monty’s first attentions to Mary there was a change. The “mystery woman” had long since vanished. He began paying more attention to his clothes. He no longer hid from his fans. He went out more. Montgomery Clift, even while he had not chosen to permit material possessions to dominate his life, had known such things from childhood. Drawing on his background, he became an attentive escort for Mary.

His dates with Mary continued in New York, where Mary’s parents live and which he still regards as his home. Hand in hand, they window shopped along Fifth Avenue.

There was a change, too, in the sort of thing Monty was saying to reporters. Where once he had diverted all references to romance by changing the subject to work, he now remarked, for publication, that he disliked being called “a bachelor.”

“A bachelor,” he explained, “sounds like a man who intends never to marry. I want to get married some day.”

But when pressed to describe the girl he wanted to marry, he again parried, “I like all girls. All kinds of girls, but I won’t drag any particular girl into the spotlight by talking about her to reporters.”

A little later, even that attitude softened. To a columnist, he talked unhappily about a new role, and when asked about his romance with Mary, he smiled and said, “That also is good.” It was as if having attained a goal in his career, he could, at long last, allow himself to relax and live a little.

He timed his own return from a vacation to coincide with Mary’s return from a cruise.

It looked like Monty was at last in love.

But time, maturity and some good hard thinking made these two young people realize that affection was not enough for a life-time partnership. Monty was no less dedicated to his work, no less willing to ever be in a position where economics would dictate his art. Mary, moving in the family orbit of love and attention, was wise enough to know that there are some differences in purpose which cannot be bridged. Montgomery Clift, the man, was wonderful. Montgomery Clift, the artist, separating himself from normal associations with the kind of concentration which drew from him the restrained, intense performance of Prewitt in “From Here To Eternity” could never be a husband who could put social obligations ahead of his work.

And so these two wrote their own ending to what had been a delightful, warm relationship. One to dream on, but not to have and to hold.

In the Spring of 1953, Mary was married. There was no rebound aspect to their romance. Rather, it was marked by an assurance that their backgrounds, their beliefs, their obligations to each other would allow them to find together the kind of life they both wanted.

And Monty? Montgomery Clift retains that greatest and most demanding luxury and need of the artist. Montgomery Clift has his lonely freedom.

(Montgomery Clift is in Indiscretion of an American Wife.)

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1954