Why A Guy Wants to Stay Single?

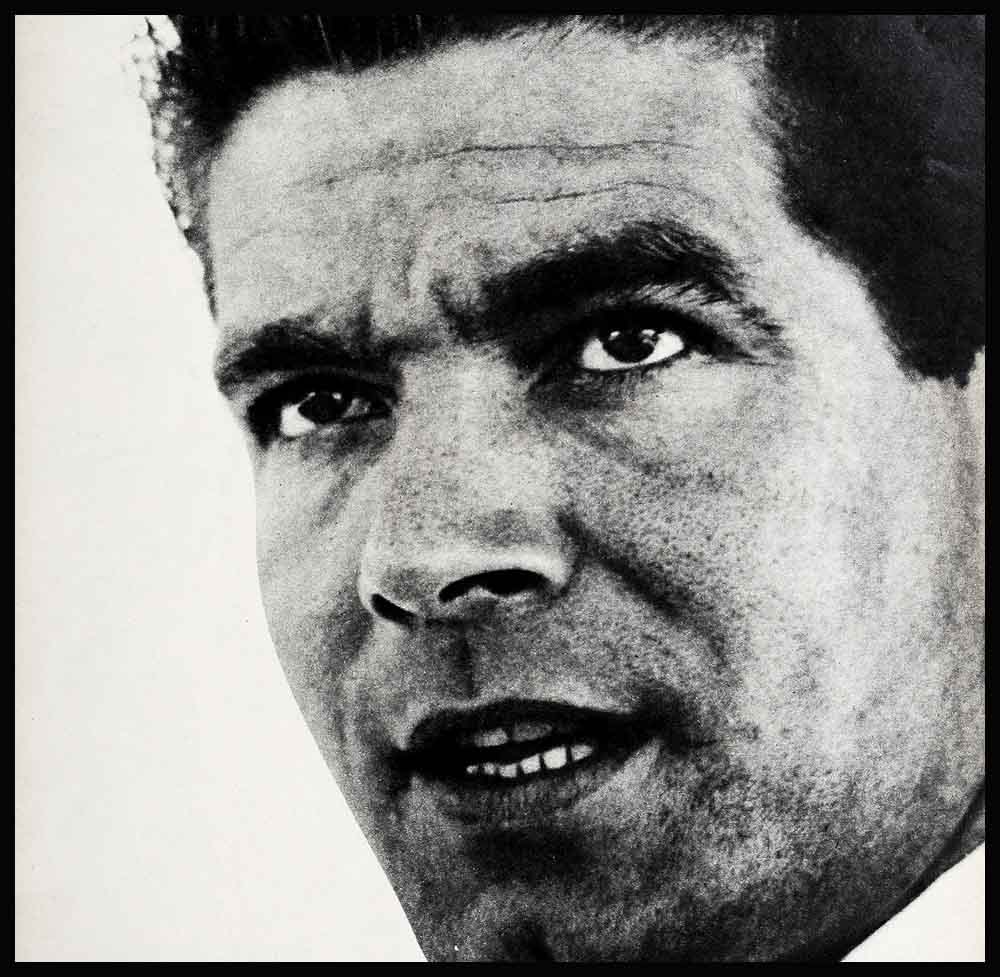

Stephen Boyd walked into the crowded 20th Century-Fox commissary recently, and despite the general noonday luncheon confusion, there was hardly a female head that that didn’t turn toward his direction. Standing over six feet tall and weighing a husky one hundred and sixty-five pounds, he is a handsome man. His features are rugged and masculine while his eyes, a hazel green, add, to what might he a stem look about his face, a boyish, lively mischievous charm that seems to complement his captivating smile and unruly thick mop of curly, red-brown hair.

He is thirty-two; Irish, and after “Ben Hur,” not only one of Hollywood’s most exciting new leading men—but one of the town’s most elusive bachelors.

He dates many different women; is non-committal on all. There were rumors about him and Hope Lange, whom he met while filming “The Best of Everything.” At the same time, he is known to be interested in Elana Eden, an Israeli actress, and in Marlon Brando’s ex-wife, Anna Kashfi. And there still is Dolores Hart.

In other words, he could be married, but he isn’t. “I’m not looking to get married,” he says, simply and directly. “Between a bachelor and someone who’s temporarily unmarried, I’d definitely classify myself as a bachelor.”

What makes a man want to stay single? Is it fear of dominance by a woman? Are American women too aggressive, too demanding, too un-feminine? The question was hardly out when Stephen thundered out:

“It stops me cold,” he says, “when someone asks me what I, as an Irishman, think of American women. I think only as a man. And as a man, I find that there is no difference between American women and women throughout the world.

“I have not met an American woman who was not feminine,” he adds, seriously. “I have not met an American woman who has struck me as being more aggressive than any other woman. I think anyone who starts describing American women as something different is just out of his head. As for me, I don’t care whether she’s an American woman or not. If I find her attractive, then give me her telephone number!

“Woman—” he goes on, “takes the place that man gives her. The original authority always is with the man. If a woman has authority, she has been given that authority by a man. If a man complains he is being dominated by a woman, then he is complaining about something he asked for and is getting. If certain people say American women are aggressive, that they are becoming the bosses, don’t talk to me. Talk to the American male!

“For me,” and he said this almost resignedly, “I don’t think I ever really have been in love. None of my romances have ever been serious. Romance is different from love, and this is of ten confused. Sometimes I think men are more romantic than women and for this reason, a woman sometimes must understand a man better than he understands her and love him for what she understands—no matter how painful or different he is from her romantic image of him. A man loses something when he must compromise. And, strangely, a woman probably loses, in the end, the most. . . . I can’t explain why.

“Why do some men want to stay single? Maybe, it’s better to ask, Why should a man marry? A woman must understand what a man is looking to find in her and in marriage with her.

“I’m looking for something that I came very close to a few years ago. I met a young French actress and from our affinity in work grew an admiration, a respect, a loyalty—and finally a great affection. I feel that she is my friend and will be my friend for life and I will be hers. We had a friendship affection, but it was not enough to put in the form of romance. We never really considered marriage, although we did talk about it. Immediately, it became personal and we dropped the subject. But I sincerely believe that it must be possible to be in love with a woman and have that same kind of friendship. If it isn’t, perhaps I’ll never marry.”

He says this with a soft trace of brogue that still reveals his birthplace, “a tiny hamlet on the outskirts of Belfast, Ireland, called Glen Gormley,” where he was born the ninth and last child of James Alexander and Martha Boyd Millar. He is at a loss to say where his love for acting came. His father was a truck driver but he remembers his boyhood as being filled with performances in village amateur shows and by the time he was eight years old, he had already played Hamlet for a small children’s company. “I started young,” he says matter of factly, “but I didn’t get ahead much until I was ten.”

It was a group of touring players that came to town and turned his head. They called themselves the University Players. And to the ten-year-old boy who sat hunched on the step in a corner of the local hall, watching them rehearse, his chin resting on his hands and his body motionless so he would not miss a line, they were—these University Players—the most fantastic people he had ever seen.

He was sitting in his regular corner, as far out of sight as he could, when an actor came down from the stage and sat next to him. He read a script and when he finished reading four or five pages, he turned to Stephen and asked, “Why do you come here every day?”

At first, Stephen could not find his tongue and he shuffled his feet and felt the red burn deeper in his cheeks. And only after a long hesitation, did he find courage to say what he had been almost afraid to admit to himself. “Someday, I will be an actor, just like you.”

Stephen never knew whether the actor told anyone in the company about what he had said, but not too long after that, maybe two days, a man came over to him. It was after rehearsal and he said, “I am the manager of the group. Would you like to join us?” he asked.

“Can you imagine,” Stephen says today, “me a mere ten years? They probably would have sent me straight back home if they’d known. But I was tali and looked much older and they believed me when I said I was sixteen.”

He went on tour, with his parents’ permission, and “I loved every single minute of that hard, unsettled life,” he says today. “I never had any doubts this was the only way to live, even when between acting engagements, I had to work and struggle.” He worked as a waiter, and a receptionist and at so many other things that he can’t remember them all.

And if it bothered him that he never had a childhood, he never told anyone. His world was a different world from the one other boys his age had. “They would go to coffee shops and sit around and talk of conquests while I worked,” he says today, his voice neither betraying whether he would have liked to have done so or not, but simply stating a fact—that maybe, it is true: one can’t miss what one doesn’t know about—even if it is a childhood.

And by the time Stephen had worked his way to England to join a touring company, he was already a man.

But in London, instead of acting, the nearest he could get to the inside of a theater was a job as a doorman. When he was offered the job of ushering for the British equivalent of our Academy Awards, to be staged at a large London movie theater, he accepted it.

The evening was spectacular and festive and all evening long, he took the winners up to the emcee, introduced them and quietly walked away. Nothing might have happened if the emcee had not been Michael Redgrave, the well-known British actor, who has both a keen interest in the theater and in young actors.

When the evening was almost over and Stephen was standing at the sidelines watching the celebrities leave, Redgrave took him by surprise by coming over to him and asking sternly, “What do you think you are doing?”

“Why . . . ?” Stephen asked, not too certain that he were not doing something wrong.

“You’re an actor, aren’t you?” asked Redgrave.

Stephen remained silent.

“So what are you doing opening doors?”

“How . . . how did you know I was an actor?” he finally stammered.

“You can always tell,” Redgrave answered. “But why aren’t you working?”

“That did it,” explains Stephen today. “I told him why; he listened with great patience, took out a piece of paper from his wallet and wrote me a note of introduction to a small repertory company near London. And from then on, it was a breeze.”

What Stephen means by a “breeze” is that he was spotted by a London agent who smoothed him of many of his uncut country manners and his sharp Irish accent and, after that, he was on his way. Good luck caught up with him; after making the English hit film, “The Man Who Never Was,” and in Hollywood: “The Best of Everything” and “Ben Hur.”

And then, finally, early in 1958, even romance caught up with him. . . .

It was spring and he was in Rome and Rome was very beautiful. He arrived at his hotel, and not many minutes after, there was a soft knock on the door of his room. He opened it, and standing before him was a slim, young blond woman with the “most engaging manner and smile.”

“Hello,” she explained carefully, “I am Mariella di Sarzana, I am from MCA (his American agency) and I have been assigned to look after you for your stay in Rome—as long as you are making the picture ‘Ben Hur.’ ”

“Come in,” was all he could find to say.

After that, when he was free, he would telephone her and ask, “Would you like to show a visiting actor what Rome is like . . . the Colosseum, the fountains, the ruins, the Vatican—everything,” he would say. And then afterward, they would drive out into the sun-baked countryside, sometimes with a picnic basket, other times they would stop in the small villages or towns for something to eat. It was on one of these days, as they walked by the shore of a picturesque Italian fishing village, Stephen turned to Mariella and asked her softly, “Will you marry me?”

“I honestly thought this was it,” he says earnestly. “She was lovely, attractive, and a wonderful girl. She was clever and cosmopolitan, too, and just about everything seemed to point to everlasting love.”

A few weekends later, they flew to London for the ceremony . . . but their life together seemed doomed from the start. Stephen’s work seemed to get in the way, as never before. “Just after the wedding,” says Stephen, “I received a cable from my studio telling me to be sure to be back very early on Monday morning. That gave us not even a day before I had to fly to Rome again.”

Together, they raced back to Rome, only just in time for Stephen to rush off to the studio.

It was a busy day for him, that Monday. But even so, Stephen had felt sure he would spend it thinking about Mariella, about their new life together, about their love for one another. Yet he was surprised.

For all that day, he could think of nothing but his work and his portrayal of Messala.

And it was like that for the rest of the week . . . and the next. Exhausted, he would come home at the end of the day to drop into a chair, pick up a script, and lose himself in preparation for the next day’s shooting.

Mariella tried to be understanding. She tried to reason that, after all, while a marriage is a career, a fulltime occupation for a woman, it is only part of a man’s life. His outside life is still vitally important to him. Yet it was hard for a bride to be neglected. . . .

Sometimes, thinking perhaps it would be kinder to distract him for a few hours in the evening—so that he might have a little relaxation—she would walk unexpectedly into the room where he was concentrating, and start talking to him about nothing in particular.

At first he could try to shut out her voice, but finally his concentration would be broken and he’d wheel around, eyes flashing with irritation and snap, “Honey, please don’t disturb me when I’m working.”

Officially their marriage was dissolved a little more than a year later, but it was over, to all intents and purposes, a month after they had recited their marriage vows, when Stephen had to leave Rome for Hollywood . . . and Mariella did not go with him.

Some say she was reluctant to leave her native Italy; others point out that she was hurt and resentful for the way Stephen had neglected her.

“But it wasn’t really an unhappy marriage,” Stephen himself explains. “It was an unsuccessful one. Just a question of two adults making a mistake. It’s that simple. Both of us had the courage to recognize it, and this way neither one feels hurt. And I do believe,” he adds, “that the decision to get married after only three months courtship was what was hasty—not the decision to divorce after less than a month. There was no point in prolonging what we both knew to be an error.

“A husband and wife must be friends first. You cannot get to know someone in three months . . . friendships are not made that easily. You need time to know what you aspire to—for yourself and for the other person; to know what you are looking for in life and in marriage, also.”

And what is Stephen Boyd looking for in a wife?

Today, in Hollywood, where he has resumed his bachelor existence, he seems more reluctant than ever to give it up. He says simply: “You can be certain I’m not in any hurry to put my head in a noose for a second time.”

But he does say that if a girl is fun-loving and good to talk with, if she has a sense of humor and a sense of values, he will find her attractive and want to know her. “But she need not know anything about acting, or my work,” he adds. “Even though a man’s occupation is his first love, when I am out with a girl, very little shop talk ever enters the conversation. I make sure of that.

“There are so many other things than work to talk about and find out about,” he says. “Like the wonderful life here in America, its people; there is food; there is the different attitudes toward living that people have in various parts of the world . . . all sorts of wonderful things. If an actor can only talk about acting, then he must be a very dull person; and this is true for any woman who can only talk about what she does. And because I was so poor so long,” he says, “I value things. I try to absorb pleasure and I would like the woman I am with to feel the same.”

She would please him, too, if she liked golf and tennis and if she knew a little about baseball. “I became a fan last year,” he laughs at himself, “and no one talks to me when a baseball game is on. They—or she—wouldn’t dare. I’d go out of my mind.”

And if she could be prepared to follow him anywhere and live anywhere in the world—“I’m very uncertain. I don’t know yet where my future lies, here or back again in Europe,” and if she could love the out-of-doors and not be afraid of being too unsettled. . . . “You see, I’m a rambler,” he tries to explain. “I guess you might call me an Irish rover. Anything that’s going to stifle my life—let it go somewhere else. I don’t want it. That does not mean that marriage is out of the question. It’s just that I don’t think marriage is necessarily something that has to be within four walls. If she were another rambler . . .” he hesitates and never finishes the sentence. But it’s pretty obvious what Stephen Boyd means is that just about any bachelor can be made to change his mind about being single if the girl is willing to take the time to understand him and offer him a lasting friendship along with her love.

THE END

SEE STEPHEN BOYD IN M-G-M’s “BEN-HUR.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1960