One Unenchanted Evening

Last summer, the day after Rosemary Clooney became the wife of Jose Ferrer, a New York publicist stood on a loading ramp at La Guardia airport waiting to board a plane for Paris. His nose was buried in a newspaper, and he kept shaking his head in disbelief.

“Impossible,” he muttered, “impossible . . . impossible.”

A companion looked over his shoulder. There didn’t seem to be anything particularly unusual on the page. A story about a man getting a ticket for starting an argument with a policeman. A squib about an Iowa picnic. A few ads and fillers. And a photograph of half a dozen people with a lengthy caption. The companion was puzzled.

“What’s so impossible?” he asked.

The gate opened and the passengers headed for the plane. The publicist threw the newspaper down on a counter and went aboard.

“Some day,” he said to his friend. “when we have lots and lots of time, I’ll tell you how incredible it all is.”

The paper lay on the counter with the photograph face up. Included in the picture were Rosemary Clooney, Jose Ferrer, Olivia de Havilland and a few members of the cast of a musical Jose was appearing in at Dallas, Texas. The caption explained that it was a wedding party and that Rosie and Jose had been married the day before after a courtship of more than a year. This may not have seemed so impossible to most people, but it did to that publicist. He knew the whole story. As a matter of fact, he was the fellow who introduced them. And he was the chap who had bet a hundred to one just a few weeks before that they’d never marry.

It all started about two years ago, a few days after the release of Rosemary Clooney’s big record “Come-on-a My House.” It was bitter cold in New York, and Rosemary was sticking close to the phone, waiting for sales reports on her record.

A lot of friends had been dropping in all day and Rosemary sat cross-legged on the floor chatting with them when the publicity man dropped in.

“I just left Joe Ferrer,” he said, “and he was telling me how much he admired you. He said he’d like to meet you.”

“Joe Ferrer!” Rosie retorted with a laugh. “You mean the actor-writer-producer director genius star of stage, screen, radio and everything else? When would he fin d the time?”

“He d make it. He asked me to arrange lunch or something.”

“Isn’t this genius married?”

“Well, yes . . . and no. They’re not really working at it.”

“I think,” said Rosie, “he’s too talented for poor little me. Tell him to go find a pretty girl. I’m just an ugly Kentucky singer.”

There was a lot more talk about Jose Ferrer that afternoon, very little of it too complimentary. Not vicious. But the idea of Ferrer, the cosmopolite, and the Kentucky band singer was just too, too ludicrous as a combination. At least that’s what Rosemary thought. And then they spoke of other things.

It was a couple of weeks before Rosemary heard about him again. And it was from that publicity man again. He was associated with Ferrer in the production of a play, “Twentieth Century.” He telephoned Rosemary.

“Look,,” he said, “Joe and I are giving a party at Sardi’s after the opening tonight. Why don’t you come?”

“This the same Joe?” asked Rosie.

“Of course. He says he’s just got to meet you.”

“I don’t understand it,” said Rosie, “but I’ll come. Can I bring a couple of friends? We’d just like to catch this kid’s act.”

That night, after the theatre. Rosie and a couple of pals went to the party, The usual Broadway crowd was there—the actors, agents, musicians, press and rival producers. Rosie and her friends took a table-and Jose was suddenly there, as though someone had rung for him. There was no chair—and Rosie didn’t suggest he get one.

The man has charm and he used it, but Rosemary, fully aware of the business she was getting, pretended she hardly noticed him. And when he was called away from time to time to visit with other guests, Rosie and her chums had great laughs at his expense. In simple language, it was not love at first sight.

For a month at least, following the Sardi’s party, the publicist, now anxious to drop the entire matter, was prevailed upon repeatedly by Jose to call Clooney and arrange that lunch date. It wasn’t public knowledge at the time, but Jose and his wife were on the verge of divorce—and he said he was lonely. But Rosie wouldn’t cooperate.

Finally, Joe abandoned his contact man and set about his own courtship. Now nobody claims that Jose Ferrer is even close to being handsome. But anyone who knows him will tell you that the little fellow can fascinate any woman of any age out of her bridgework.

The first time the Ferrer flowers arrived Rosemary sat and laughed. Too many flowers for one person. The next day it became a problem. Where to put them. The third day she was sore. The roses were a burden. And then she began to wonder what kind of fellow this Ferrer was. Hundreds of expensive flowers all over the place. Rosie got more flowers from Jose in a week than she had had in her entire life. The man was either nuts or he really liked her.

Up to this point in her life, Rosie had never had a real boy friend, except for one year of long-distance romance with Dave Garroway. This was an odd affair, which consisted mainly of Garroway’s phoning from Chicago at intervals and telling her his symptoms. Garroway is just as off-beat a fellow in real life as he is on television. once every few weeks they’d meet at some half-way point between Chicago and New York, and by the time Dave got finished telling her his problems they’d have to part. It wasn’t a very fulfilling romance and pretty one-sided. Garrroway didn’t ever think to send flowers.

The posey operation was the right approach to Rosie. She began to wait for Joe’s inevitable phone calls, vaguely amused at first, later on with a slight anticipation and finally with eagerness. And when finally the actor did ask her to lunch Rosie just said, “Where? When? What time?”

Rosemary Clooney was a gone goose before the soup was gone, She had never known anyone like Jose before. The men in her world were the kind who spoke only of “platters” and “arrangements” and “new sounds.” Ferrer talked of the theatre, philosophy, languages and horticulture. He was using an Oscar as a door stop (for “Cyrano de Bergerac”), had one hit play on Broadway, two more opening and a head full of cultural plans for the future. And he spoke about all these things as though they were to be shared by Rosie.

The next day Rosemary’s friends were astonished to find a large picture of Jose in front of the morning’s flowers. Somebody made a small joke—but it fell flat.

Jose Ferrer’s courtship of Rosemary Clooney was completely dignified, if a little “Pygmalion” in style. The actor, because of his situation with his wife, was emotionally restless and seemed to need the comfort of the singer. She gave it willingly. And the odd arrangement soon became the talk of Broadway. Her personal circle just couldn’t figure it out. They couldn’t see what Rosie saw in Jose, or, for that matter, what he saw in her.

Then Rosemary was called to Hollywood. This had to be the end, her friends thought. Jose headed for Paris, and eight thousand miles separated the lovers.

Rosemary Clooney’s romance was the one thing that worried her new bosses at Paramount. Ferrer was a married man. Though the word was out, of course, that his wife was going to divorce him, it wasn’t official. The general hope was that the love would wither from neglect, but Rosie continued to walk around with her head in the clouds.

While Jose was stumping around Paris streets in the make-up of Toulouse-Lautrec, Rosie was spending her spare time sitting in the garden of a huge Hollywood home staring into space. There was just one rule in that house. When the phone rang, Rosemary had to answer it first. It was usually Jose calling from Paris. And if the instrument remained silent for more than a couple of hours, Rosie placed a call.

When her first picture was finished, there was a little trouble at the studio. Rosemary picked up a passport. The word got to the front office that she was going off to see her boy. This, from the studio’s point of view, was madness. Her first picture presented her as a clean-cut kid who might fail in love with a Princeton lad, but couldn’t in a million years figure as the corespondent in a divorce suit. The best talkers in the plant went to work on her—and a deal was finally made. If Rosie Would delay her trip until Mrs. Ferrer could get into court the studio would treat her to a trip abroad with all expenses paid. It was more than likely common sense that made Rosie change her mind (not the promise of the trip) but she did agree to wait—and everyone breathed a lot easier.

During this period of tension the only person who felt entirely certain that this was all a game was Jose’s old friend, the publicist. de was asked one day if he thought Jose would marry Rosemary. Absolutely,” he said, “positively not!”

“But what about all this attention?” he was asked.

“Ferrer must have this to live,” was his pat answer. “Like you must have bread,

Joe must have a woman who will listen to him, a woman to jump when he cracks the whip. But he won’t marry again. Not in a million years!”

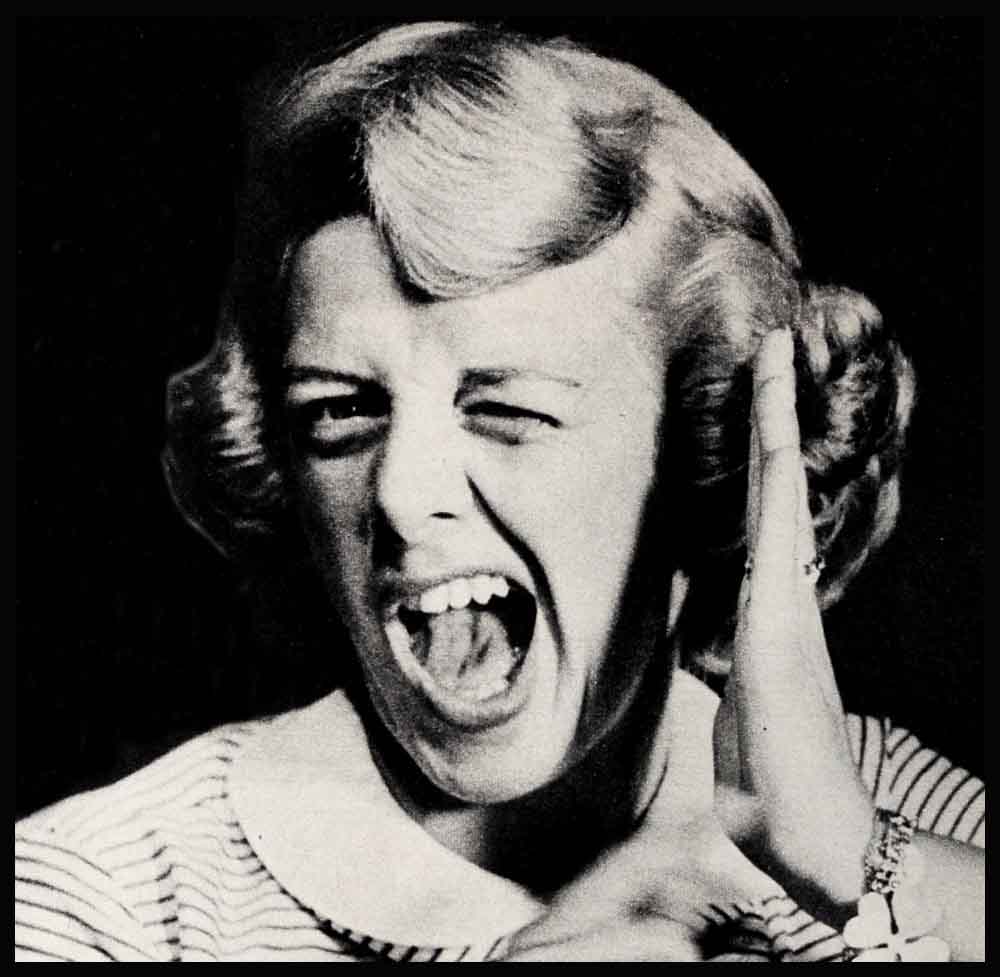

Other Ferrer acquaintances, however, had a different story to tell. Zsa Zsa Gabor, who had worked with him in “Moulin Rouge,” complained when she returned to America, “Some men fall in love and are still sensible, but this man is impossible,” she said. “He is all the time on the telephone to Rosemary in Hollywood. He wouldn’t even look at me!”

The way the story ought to go from here on is familiar to all readers of romantic fiction. The man comes home, his domestic matters are settled quickly in an attorney’s office and the pair live happily ever after. But it wasn’t that way at all. Jose came home, asked his wife for a divorce and she told him she’d think about it. Rosie got the wind up and and in a flash the whole situation was reversed, with Rosie in the driver’s seat, Jose begging for time, and Rosie telling him to get the matter settled or get lost. And for the first time in his life, Jose Ferrer found himself unable to master the situation with a few well-selected quotations.

It didn’t get in the papers. As a matter of fact, few of their close friends knew about it, but for several weeks the romance between Jose and Rosie was kaput. Probably for the first time in his life, Jose was in love. And miserable.

The ex-Mrs. Jose Ferrer was furious about the whole thing. She’d get a divorce when she was good and ready. Solicitors for Jose went to her and told her Jose was in love and likely to lose his lady unless she got a divorce but fast. Her comments added up to something like “Wouldn’t that be a pity.”

And Rosemary was adamant. Marriage was on her mind. Marriage or nothing. Her father came to California to see her and bolstered her attitude. So there came a period of waiting for Rosie—and a period of sweating it out for Jose. There were times when he could hardly realize it was really Jose Ferrer in this muddle. The lover, the suave one who had made practically a profession of loving and leaving was now in the position of having to apologize to one woman for dumping her—and to another for keeping her waiting.

They say it cost Jose a good deal in self-esteem and money, but finally his attorneys arranged a settlement with his wife—and in the nick of time, for Rosie was just about to call the whole thing off. Joe was in Dallas, Texas, appearing in a play when the news came. Mrs. Ferrer had flown to Mexico and had divorced him and flown right back to New York. Joe was a free man. He picked up the phone and called Rosemary for the first time in many days. She was hard at work in “Red Garters,” but she took the next plane to Texas.

Two days later they drove the ninety miles to Durant, Oklahoma and Rosemary and Jose were married at long last. Back in Dallas they posed for a picture with the cast of Jose’s play—and it was printed in the New York tabloid that the publicity man saw.

The Jose Ferrers are a local couple in Hollywood now. They own a fine house on one of the better streets and they plan to raise a family. They don’t mix much in Hollywood circles, for Rosemary has developed some of the Ferrer aloofness and is more interested in the quiet life than the hoopla that goes with being a movie star. Rosemary, they say, is the boss of the family, but you can’t be sure. The day after they moved into their home those flowers began coming again. They’ve come every day since.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1954

No Comments