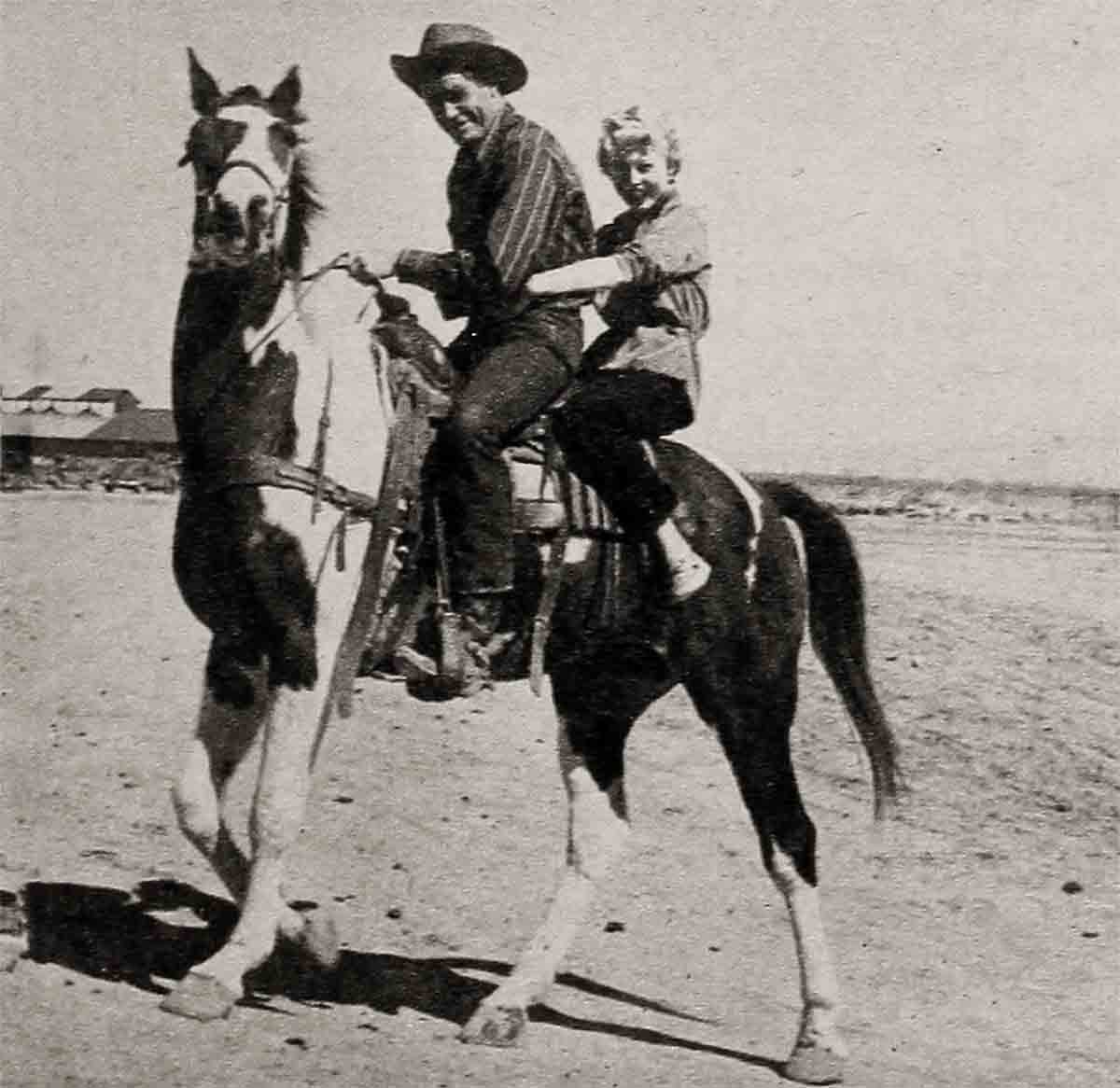

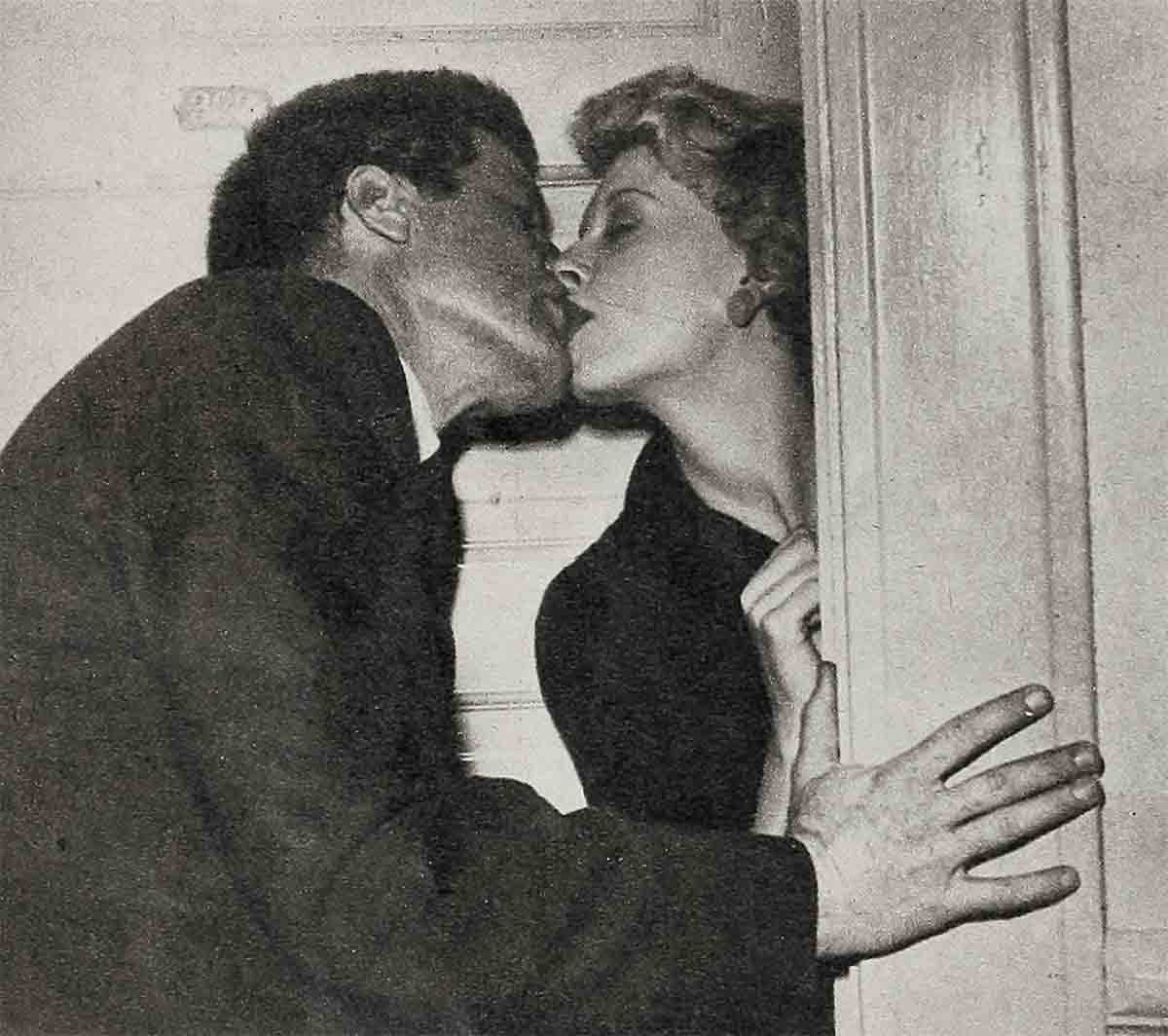

Love’s Young Dream—Barbara Ruick & Robert Horton

Barbara Ruick and Bob Horton are one of the brightest young couples on the Hollywood horizon. She is the daughter of radio actress Lurene Tuttle and radio actor Melville Ruick, and her two-year-old contract with MGM has put her in such pictures as Above and Beyond, I Love Melvin and The Affairs of Dobie Gillis. Barbara herself has put even more into her movies than was expected in the wildest dreams of studio executives, and as a result she is slated for the big time on that lot. A star dressing room is also waiting for Bob, whose portrayals in The Arena and The Bright Road mark him as an unquestionably fine actor.

Come August, all this talent is going to be lumped into one family, when Barbara and Bob exchange their vows in front of what they both agree will be a “small altar.”

There has been plenty of time to discuss the wedding, the kind of house they want, and whether or not they’ll install a garbage disposal unit, keep parakeets and have children. Long engagements versus short engagements make a frequent subject for debate, and Barbara admits she would have been willing to marry Bob 24 hours after Cupid let go with his arrow. Twenty-four hours, she figures, would have been more than sufficient to gather up her wedding dress, the license and the dime for her shoe. But because Bob’s interlocutory divorce decree will not be final until August, Barbara has been forced to endure an engagement period of almost a year.

“And you know, I’ve decided it’s a good idea,” she says. “It gives us time to iron out the kinks.”

None of the so-called kinks are very serious, as their temperaments seem admirably suited to each other. They agree on many things, including the fact that the least likely way to spend an evening is a siege at a plush nightclub. If you really wanted to find them after working hours, the best bet would be any little restaurant where there is a torrid piano player. Barbara would be the brown-eyed blonde who is so engrossed in the music, and Bob would be the handsome man with red hair, the one wearing the patient, puzzled expression. The pianist comes to a highly stylized phrase, and Barbara half rises from the chair in her excitement.

“Now what did he do?” says Bob.

“Didn’t you hear that?” she says. “About two bars back. Those were the licks I’ve been telling you about.”

Bob shifts in his chair. “Now, go over that once more for me—lightly. You mean when he hits the keys in sort of an off-beat way—”

“That’s it—that’s it! Now, listen and see if you can tell me when he does it again. I’ll make you a jazz fan yet!”

If you wanted to find them during the day, look around any sports stadium. Baseball, football, basketball, it doesn’t matter—if it’s a good game, they’ll be there. Barbara is the one who is either staring intently at the field or plying Bob with questions about technical points of the game, which he answers as fast as she asks them.

Since last fall, when love bloomed between them, they have had a liberal education concerning each other. Bob wants desperately to be a hipster so that he can share her enthusiasm for jazz, and Barbara has discovered that he has an excellent singing voice which she thinks with a year’s training could be slightly sensational. Bob has found out that his future bride can whip up an excellent dinner, and Barbara was pleased to find that while she never enjoyed cooking for herself, it developed into a pleasure. when she was doing it for Bob. She likes Chinese food, which he loathes, and he likes Mexican food which sends Barbara’s digestive system into a snit, so they compromise at Italian restaurants. They have discussed at length the affect of their combined careers on their coming marriage and feel they understand the other’s work so well that they will be able to iron out any possible wrinkles.

The attraction that has grown between them has been a gradual thing. They first met more than a year ago in the office of MGM dramatic coach Lillian Burns, and it was a matter of “How do you do, Mr. Horton?” and “Quite well, thank you, Miss Ruick.” They worked together for several weeks in Apache War Smoke, and although her mother had once told her, “If an actress doesn’t fall in some small way for her leading man, there’s something wrong with her,” Barbara felt nothing but professional respect for Bob. The picture was finished in June and it wasn’t until two months later that they had their first date. Barbara was so unimpressed at the time that by now she barely remembers the evening. It is her dim recollection that he came for dinner to the house shared by her with studio publicist Jean MacDonald, and that they talked afterward and he went home early.

Their dates grew more frequent and slowly Barbara began to notice his sincerity, his truthfulness and above all, his complete respect for her. She decided that here was that rarity in this modern world, a gentleman; and soon realized she was happiest when she was with him. Following his proposal of marriage they discussed architecture and found that both like “comfortable modern”; then weddings, which both agree should be small but definitely inside a church; and then babies, which both want in quantity, but only after they have enough financial security that Barbara can take a year away from work to stay home and care for each new addition.

Barbara has learned to distinguish a feint from a dodge, an infield fly from a Texas leaguer, and a touchback from a safety. Bob has found with delight that she is an avid sports fan, and last March when she visited him on location for Arena in Tucson they not only went riding every day, but when the cast and crew organized a disorganized football game on the set, Barbara got into the act.

“I will now,” she announced, holding the ball daintily between her hands, “do a drop-kick.”

“Be careful!” yelled Bob. “You’re wearing flat shoes—you can’t dig in! Honey, you’ll go flat on your—”

Which she did. It was one of the things that have proven to Barbara that she should listen to Bob’s advice. Before she met him she had always felt rather maternal toward the men she dated. Secure in her personal life as well as her newfound career, she tended to be self reliant and so was forever on the lookout for ways in which she might help other people. Mr. Horton has modified all this, and now Barbara realizes that she tends to be high strung, to fly off the handle quickly, and Bob’s comparative calm and good sense have a leveling affect on her own high spirits.

There was good reason for her self-confidence. Barbara grew up in the world of show business, the daughter of two highly succesful professionals who were famous not only for their talent but also for their charm and their circle of delightful friends. The friends were also in show business, and it was only natural that Barbara should develop at an early age into a mite-sized performer.

She inherited acting ability from both parents, and at five was already dreaming up her own skits. “I must have bored everybody to death in those days. I’m still a ham—I should never eat pork.”

From her father, who once played the violin and had his own band, Barbara was endowed with musical talent, and from her mother, who is still an avid jazz fan, a love for all kinds of music. As a result, today she is equally valued as both an actress and a singer, and Barbara loves both so well that she is incapable of choosing between the two.

A lot of practice went into both fields. Her girl friends were enlisted in the production of her plays and soon found themselves relegated to making backdrops out of old sheets and bright crayons. If any of the other girls had ideas of their own they seldom had time to put them across, as the small Ruick was a whirlwind director who scurried everyone else to routine jobs while she took the spotlight. Audiences were drafted from the neighborhood and, as Barbara puts it, “they looked whether they wanted to or not.”

Lurene Tuttle had never pushed her daughter into theatricals—Barbara fell into them by herself. Her parents were naturally delighted, but they continued their attempt to seem disinterested and periodically suggested that it would be nice if Barbara grew up to be something distinguished, like an editor of Vogue magazine. All along Barbara knew, despite her youth, that if she had turned into anything other than an actress her parents would have been crushed.

As Barbara persisted in her thespian interests, Lurene Tuttle began coaching her daughter, beginning with pantomime, and Barbara feels that such fantastic and rigorous assignments as being a squeezed lemon or a tree in May were a valuable beginning for her education in dramatics. When she was eight she battered her way into the billing of a recital and chose for her stint a rendition of “Waiting At The Church,” a la Beatrice Kay, for which she was to be frocked in her mother’s wedding dress. It was bad enough having to hitch up the dress so that she wouldn’t trip over it, and even worse when the air raid sirens cut loose and the house lights went out. But her father, sitting in the front row, trained the beam of a flashlight on her, and the small Miss Ruick went through her performance with the nonchalance of a seasoned trouper.

When she was 14 she began singing with the high school band and organized a singing group that appeared twice weekly on a San Fernando Valley radio station. The accompanying skits were written by, naturally, Barbara Ruick. She never went to a party or a prom when she didn’t sing, and always returned home with the seven-dollar scale wage tucked away in her evening bag. When she was 15 she fluffed for the first time, in a local little theater production of Stage Door. She delivered her lines, “I don’t really want to leave. I don’t know what to say.” Following that she really didn’t know what to say, and solved the situation by walking off the stage.

She wasn’t so shaken by the experience that she lost confidence. Less than a year later her mother, who played “Effie” on the Sam Spade radio show, became too ill to go on, and Barbara marched into producer William Spier’s office. “You just have to let me do it,” she said. “I’m the only one who sounds like mother. And besides, it’s the only thing that’ll get her out of bed. If I do it this time, she’ll have to come to your rescue next week.”

She got the job, and it was the last time Barbara was nervous during a performance. It gave her a confidence which has never left her, except perhaps for the times when her mother has been in the audience. Barbara can’t explain these reactions—she thinks it may be because she’s trying so hard to please, as she did when she was a small girl. She recalls the day she marched two miles in a Girl Scout parade as the flag bearer. All went well until she came to the corner where her mother stood. Then Barbara tripped and went flat on her face. Lurene Tuttle was in the audience the night Barbara forgot her lines in Stage Door, and stranger still, she gave a top-notch TV commercial one day until toward the end of the spiel, when her mind went blank. When she got home she learned that her mother had turned on the program at the precise moment Barbara had fluffed.

Barbara reached the age of 12 before her parents were divorced, and those years of living with show business parents have given her a wisdom that may well help in her own marriage. She feels that she knows the pitfalls of a marriage which combines two careers, what to say and what not to say at the right moments. She was and still is extremely fond of her father, who has remarried and lives in New York, but the divorce itself did not affect her nearly so much as the death, a year before, of Lillian Johnson. Miss Johnson had been Barbara’s nurse since babyhood, a wonderful woman who, childless herself, poured out her maternal love on Barbara. She taught the child to love people, she was a second mother to her and her most appreciative audience all through Barbara’s childhood. She died on August 15th, and for this reason Barbara has set her wedding date on that day. She intends sending a little prayer up to heaven, in the hope that her beloved old nurse will be able to look down and see Barbara on the biggest day of her life. It is her deepest regret that Miss Johnson cannot be here to see the children that will come some day.

Following the divorce Barbara lived with her mother, who continued to guide her through an adolescence that was devoted almost entirely to theatricals. Their relationship is extremely close, and even when Barbara decided to learn about drumming, Lurene Tuttle didn’t complain. It all started when Barbara sang with an orchestra made up of college boys, and when drummer Gene Estes left his stand to do a vocal, Barbara would hop up behind the drums and beat out the rhythm for the band.

Two days after her 17th birthday Barbara took off for New York. Determined to make the grade on her own merits she purposely avoided letting anyone know her relationship to her famed parents. She moved into an apartment with four models and proceeded to pound pavements like a novice from Hatsoff, Texas, but her talent shone through. Out of 800 applicants she was chosen with only nine others to appear on Chico Marx’s “College Bowl” TV show. Soap operas and commercials followed, and after a highly successful year she returned home to Hollywood, where she shortly copped a contract with MGM. There she went to work with such zeal that studio employees weren’t surprised when, during the filming of The Affairs Of Dobie Gillis,Barbara insisted on completing her dance routine despite an attack of flu, and stopped only when she fainted from exhaustion.

At first she lived with her mother, who had remarried, then moved to a small apartment in Hollywood, another in North Hollywood, then to Westwood, then shared a house with Jean MacDonald, then, because the landlady didn’t cotton to Barbara’s boxer puppy, the two girls moved to another house. Barbara currently is living with her mother again, and has stored a pile of furniture collected in the last two years in the last six residences. There will be enough, she says, to fill any house she and Bob might buy on his GI loan, and she promises that, for a change, she will really settle down for keeps when she gets married.

She has already begun to settle. An incurable mimic, Barbara comes back from New York dropping her R’s, back from Alabama accompanied by a southern drawl. She imitates anything, including the makeup worn these days by New York models. When living in Manhattan with the quartet of mannekins, Barbara was enchanted by their black slipstick and penciled lines beneath the eyes. She had arrived in New York with a healthy, scrubbed look, but by the time she came back to Hollywood a year later she was all but suffocated in cosmetics. Lurene Tuttle met her at the airport and couldn’t help smiling. “My word,” she said, “You have been sick, haven’t you?”

After a year of doe eyes, and after a few dates with Bob Horton, Barbara decided to give up the ghostly look, that this was not really for her. The next time Bob called for her at the house, he was met by a pert face that boasted nothing but lipstick—red lipstick. He took an appreciative look, but said nothing.

Barbara couldn’t stand it for long. They hadn’t been in his car five minutes before she turned to him. “Well—do you like me better this way?”

He reached over and took her hand. “I liked you the other way, too. But this is fine.”

“You see what I mean,” Barbara says to anybody who will listen. “Bob is a gentleman, a real gentleman. And furthermore, my red-haired mother is charmed right out of her shoes at the idea of a red-haired son-in-law. I was obstinate—I didn’t have red hair—but now she has more than a 50-50 chance of having carrot-tops for grandchildren.”

Everybody’s happy, including MGM, future in-laws, the growing legions of Horton and Ruick fans, and most of all, Barbara and Bob.

THE END

—BY SUSAN TRENT

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1953

No Comments