The Very Private World Of Diane Varsi

All right, Mother. I’ll say something. As soon as I can I’m going to get up, pack my things, and leave. I never want to see you or this town again,” Diane Varsi whispered. Then she put the script down and looked up.

Across the room, Mark Robson was staring at her. He licked his lips. He cleared his throat. “You read that,” he said finally, “as if it were the story of your life.” He shook his head. Then, slowly, he added, “I’ve been making movies quite a while now. I’ve heard a lot of girls read for parts. I’ve never seen one who looked like you or behaved like you. I don’t know what sort of person you are. But if you can get your life into a line like that—the part is yours. Congratulations,” he said.

And Diane Varsi, who had been nobody five minutes before, walked out of the studio with the key role in Peyton Place in her pocket, and headed back for the slum in which she lived.

It was true that no one had ever shown up for an audition looking as she looked. Her round face with its tip-tilted nose, uneven complexion, and serious blue eyes was neither pretty nor winsome—and she had made no attempt to improve it. There was no lipstick on her mouth, no powder on her nose. Her cropped, cinnamon-colored hair looked as if it had been coiffeured by an electric fan. She wore beach shoes, drab black stockings, a shaggy turtle-neck sweater over a plain grey skirt. Around her neck she wore her one piece of jewelry, a wave-washed rock she had found on a beach, drilled a hole through, and suspended on a string. She had walked in to read for Mark Robson looking like that, and she had not smiled, she had not chatted; she had mumbled, “Hello,” stuck out her hand, and then retreated into a corner with the script until he was ready to begin.

But at the end of the reading, she had read, “All right, Mother, as soon as I can, I’m going to pack my things and leave”—and all of her strange, tortured nineteen years spoke in it. And the part of Allison in Peyton Placewas hers.

Two marriages finished—at nineteen

Hollywood has known many ‘different’ people, from many different worlds. The stories their biographies tell range from the gypsy background of a Yul Brynner to the criminal youth of a Rory Calhoun, the loneliness of a Barbara Stanwyck.

But never before, even in Hollywood, has there been a story like that of Diane Varsi.

She was nineteen, and already she had been married twice, separated twice, and borne a son.

She has been literally starved, both for love and for food, literally beaten within an inch of her life. She has lived in tarpaper shacks and slept in box cars, expelled from schools and picked up by the police. She is in Hollywood today only because one morning in 1955 she told her mother, “I’m going out for a walk. I’m going to walk and walk and walk. And I may not come back.” And she had added: “It’s a pilgrimage—of a sort.”

She took her sleeping bag that day and packed a wicker basket full of hardboiled eggs, lemons and apples—and some songs she had written. With a girl friend she hit the highway, heading south, hitching rides. She slept on beaches, and talked to other kids on the loose who told her, “You’d better go back—they’ll put you in jail.” But she kept on, flagging trucks, working here and there, and one day at the age of sixteen she found herself in Hollywood, where she hadn’t the slightest intention of being.

And even then, it was a long time before life began to look any less like hell for Diane Varsi.

All her life she has been sure of one thing and one thing only: anything she loved would be taken away from her. So she had decided that it was better to learn young not to love at all.

She was born—sixteen years before she started out on that long walk to Hollywood—in St. Mary’s Hospital in San Francisco. That was February 23, 1938. Her parents, an Italian-American florist named Russell Varsi and his pretty French wife Beatrice, received her with joy. She was their first child, and they welcomed her. Thirteen weeks later they learned that their baby daughter had developed a blood disease. They dug into their small savings to provide transfusions to be injected into Diane’s ankles to keep her alive. As long as they were together, the Varsis never begrudged her whatever money they could spare—or couldn’t spare.

Never enough time

It wasn’t that Beatrice DeMerchant Varsi was a neglectful mother or a cold one. Diane remembers her as loving, gentle, and so patient that even when she was in a hurry to go somewhere, she’d let the baby Diane achieve the dignity of tying her own shoelaces, though the struggle might take half an hour. But somehow there were so many places that Mama did have to hurry to. With good reason, of course. Times were bad for the Varsis. Daddy sold his flower store to try his hand at contracting. Gradually, he made a go of it. A few years later, he was making an excellent living. But at first he needed all the help his sensitive, intelligent wife could give him. Of course, she gave it. But Beatrice Varsi was not a strong woman. Her health had suffered when Diane was born. When a second baby, Gail, arrived two years later, she was almost an invalid.

So it was a good thing Diane knew how to tie her laces. By the time she was three years she was putting on her shoes to start out for Grandma’s house—five long blocks away—alone.

To Grandma’s house

It was a trip she made often, in search of someone to watch over her.

At Grandma’s and Grandpa’s there was love, and in abundance. They clucked over their high-strung, pale little granddaughter, tried to fatten her up, to comfort her woes. They curled her long blonde hair, told her how pretty it was. They gave her a little china figurine one day, to play with. Diane stared at it with awe. So delicate—so pretty—and all her own. She saved her pennies to buy another. Daddy came home from his long, hard hours with, sometimes, a tiny glass animal to add to her collection. Even at five, Diane took care of them, washing them, polishing them reverently with a soft cloth, spreading them out on the floor to admire. One morning she arranged them in the hall of her parents’ home to catch the morning sunlight on their shining surfaces. A neighbor opened the front door suddenly, and smashed them all to bits.

She was only five, but Diane didn’t cry. She stood up with tight lips, stared at what had been her most-loved possessions—and walked away.

“After that,’ she says now, “I never kept anything. Nothing. Not even dolls.”

When Diane was four and a half years old, Russell Varsi landed a construction job in Salt Lake City. Because his wife was almost helpless at that time with asthma, barely able to look after two-year-old Gail, he took Diane to Utah with him and put her in St. Mary’s of the Wasatch Convent.

To live with strangers

She had barely time to realize that she was to say goodbye to her mother, to the only home she had ever known, to the grandparents she had grown to depend upon. She left them to live, not for the last time, with strangers.

And the first thing the nuns did, to welcome the frightened child, was to clip her long, beautiful hair close to her scalp.

“I guess the sisters had to do that to me,” Diane reasons today. “They couldn’t be bothered with taking care of curls. But it was a crushing blow.”

Her family was gone. Toys she no longer dared to keep, to love. And now the hair her Grandma had so lovingly combed—that was gone too.

She lived in the convent for two years. She was the only child anywhere near so young, so she had no playmates. The older girls puzzled and frightened her, especially when they played rough games outdoors. She had never played games, having been a frail child.

She learned to be alone in the convent. She began to grow up very young.

And in her loneliness, she dreamed of many things . . . of being older, of being a ballet dancer. But mostly, she dreamed of home.

And then one day her father, who had always come when he could on week-ends, came with good news. She was to come home with him for a visit, home to see her sister, her grandparents, her beloved mother. She was almost ill with excitement. No one thought to warn her that the convent years had made their change in her, young as she was. So it was with horror that she realized, once home, that she had grown unaccustomed to love.

But she had. She didn’t know, any more, how to respond to warm arms around her, loving voices. She didn’t know how to play with Gail, how to talk to her Grandpa. She found herself longing to go back to Utah, to the sisters who left her to herself, to think her odd thoughts, dream her odd dreams.

Except, of course, that when she did return, the most beloved dream—that of home—was gone.

For her sixth birthday, that year, her mother packed a huge box full of toys and sent them to her. She took them out, one by one, looked at them soberly—and returned them to the case. All but one—a tiny flower encased in glass, which would never die. That she put in her room.

A new home, with ghosts

They brought her home, finally, because she had had scarlet fever and had almost died in the convent infirmary, despite the care of the nuns. Her mother came herself, her third visit to the convent, to bring Diane back to San Francisco. She brought her back to a new home, the symbol of Daddy’s new prosperity. It was a rambling, three-story,sixteen-room house furnished by Beatrice in extravagant French period furniture, all blue-satin love seats, gilded chairs, rococo bric-a-brac. There was not a sign of the furniture Diane remembered from her infancy. And after the simplicity, the barren whiteness of the convent, it was more than unfamiliar—it was a fright house. There were paint spots on the twisting stairs, and a superstitious servant assured her that that meant there was a ghost in the house. All about her were perfect places for ghosts to live: a big, musty attic; a dark cellar; hidden nooks and crannies from which she was sure a hand would reach out to grab her. For seven years she lived in that house, too tall, too thin, perpetually stifling screams and freezing inside with an unreasonable horror. Another child would have gotten used to it. But Diane Varsi had long since lost her chance to be like other children. For those seven years she lived in terror.

And her life outside the house was no better. When she had recovered enough to begin school, her sister Gail came down with scarlet fever and their home was quarantined. Diane was still weak and pale when she finally set out for the public school in the neighborhood to meet, for the first time, children her own age.

So she stood alone on the playground that first morning, with the sun touching her ridiculously short hair, her ridiculously tall frame, and looked about her with hope. And sure enough, a boy came over to challenge her.

“Who are you?”

“Diane gulped. “I’m new,” she blurted out. At the silly rhyme, her taut nerves snapped, and she burst out laughing. She laughed for twenty minutes, hysterically, before she could stop. The other children gathered around, to stare and to jeer. The boy who had spoken to her thought perhaps that she was laughing at him. “She’s nuts,” he said with disgust.

It brought Diane up short—her hopes tumbling around her. She gulped down the laughter that was turning rapidly to tears and flung back at him the worst taunt she could think of: “Scaredy cat!”

It was thus that she got her first beating. She was taken home with a broken arm, and both knees ripped open almost to the bone.

And the lonely little girl who had wondered how people could want to hurt each other learned that she herself would have to fight in order to survive.

But she went back to school. It wasn’t easy, either for her or her teachers. If the children wouldn’t have her—all right, she’d show them. She wouldn’t have them or their old rules, either. She refused to stand in line, to take off her coat when the others did, to come on time. They wouldn’t let her be like them—well, she’d be different. She stared out of the window by her desk all day until they painted it dark green so she couldn’t see out. It did no good. She bore home note after note to her mother:

Dear Mrs. Varsi,

Diane is an exceptionally bright child, but she refuses to concentrate . . .

But what did the teachers know of Diane’s home, of her bedridden, helpless mother’s inability to do anything about it? She got by somehow. She asked only to be left alone.

Friends to walk home with

When she reached San Mateo Junior High a strange thing happened. With their new sense of maturity, their new privileges, the youngsters became more tolerant. Suddenly Diane had friends to walk home with, someone to whisper to and exchange notes with in class. At first she thought it was a miracle; then she thought she had died and gone to heaven. When she was actually elected vice-president of her class she could easily have walked on air.

And then a new girl entered the school. With new confidence Diane made friends with her, liked her. She told the gang about her—and they cut her short. “Not her—she’s cheap.”

Diane didn’t stop to decide if they were right or wrong. It didn’t matter. All she knew was that someone else was about to take over the role she herself had played so long ago, the outsider to be ostracized, tortured, and lost.

It was too great a price to pay for her own acceptance.

“I like her company better than all of yours,” she snapped. And she turned her back forever on her hopes.

“I knew then that I’d always be an outsider,” she says now. She had good reason to know it. Bad as her school life was, her home life was worse. Her mother’s health broke completely. Her father had troubles and was often away. “Everybody was getting sicker. I had to be completely self-reliant all of the time.” For four straight years her mother never stepped, outside of the terrible house. Blinds were drawn. Housekeepers came and went. When Diane met boys—as she did in her lone-wolf ways—she shrank from bringing them home. She took dancing lessons and found occasional comfort in moving her body confidently in bizarre rhythms, in winning contests. Her loneliness, her shyness, her overpowering need for love and protection, were covered deeper and deeper by the veneer of no always been taught to be loyal. I think she did right.”

At a time like that she did not sound like a sick woman.

But she could offer her daughter no more than these brief bits of help—and the life her child led remained the same. “By then,” Diane recalls, “I was a fighter. I fought any and everything.”

She had to. She fought the girls at San Mateo High because “They called me a tramp, and I wasn’t.” She fought discipline, cut classes—but passed her exams. She fought her way through a month or two in high school in Oroville, Washington, where her mother took her for a stay with relatives.

Diane runs away from home

And from there, for the first time, she ran away.

She went with another girl—another oddball. They hitchhiked together through Oregon and almost made it to California before the police found them, and brought Diane home—or to what passed for home.

She went back to San Francisco with Beatrice, back to the house she hated, to the knowledge that her father was leaving home for good. She had dried her tears; she bore herself stoically through two more months in San Mateo High School—and then she quit school for the last time.

“I had been free,” she says. “I wanted more—”

She was all of fifteen years old by then.

She and her mother moved to a small apartment. Diane got a job, first modeling in a local dress shop, then in a restaurant.

And one day—

“I went to a girl I knew who was very smart. I told her, ‘I can’t pretend I can’t think any more. I feel guilty because I’ve been pretending I’m stupid for too long.’ ” The girl introduced Diane to two other young women, one a writer whose father was a painter. The writer told Diane to go out and discover libraries. She did. For three months straight, she sat up night after night, reading everything she could.

And she knew that above all, she had to get away from home.

A final flight

It wasn’t easy to leave her mother, now so alone. But she did it. The writer invited Diane to come live at her house, where the writer’s mother kept a home for senile old ladies. It would have been a dreadful prospect for most people—but not for Diane. She said goodbye to Mrs. Varsi. She broke clean. She left all her clothes at home except what she wore. She cut her hair, which she had never allowed to grow long lest it be taken away from her again, down to an inch all over her head. “So I couldn’t be identified as a girl or boy or anything except just a person.” A person in search of herself. Then she moved into the old ladies’ home, paying for her bed and board by helping with their care.

And she talked. She talked and listened and read and thought, trying to catch up on the world before it could pass her by. She wouldn’t date—it was too frivolous, too pleasant. On nights when other young couples walked hand in hand, kissed, fell in love, Diane Varsi read her books and wrote her poetry and slipped alone or with a friend into the smoky San Francisco bistros where the avant-garde, the odd balls the homeless—the unhappy—hung out.

“Then,” she says laconically, “I said a terrible thing and the lady didn’t want me to live there any more.”

It didn’t surprise her. She was used to giving up anything that had made her happy.

She went home to see her mother and to tell her, “I’m going for a long, long walk—”

She was beginning her pilgrimage.

And a few weeks later, she was in Hollywood.

Why she stayed there she never really knew. She had had no intention of staying anywhere, of getting attached to anything that she might lose again. What she wanted was to travel all over the country as a vagabond folk singer. No ties. No loves. No—losses.

But her friend wanted to stay in Hollywood. Diane shrugged and agreed—for a while. She found shelter with some weavers in a ramshackle Hollywood house. And there—she met a boy.

A first love

She will not talk about him now. She will not even tell anyone his name. But she cannot hide the fact that she, who had starved herself so long for love, fell in love. She married him almost before she knew him. She was pregnant before she knew the marriage was a failure.

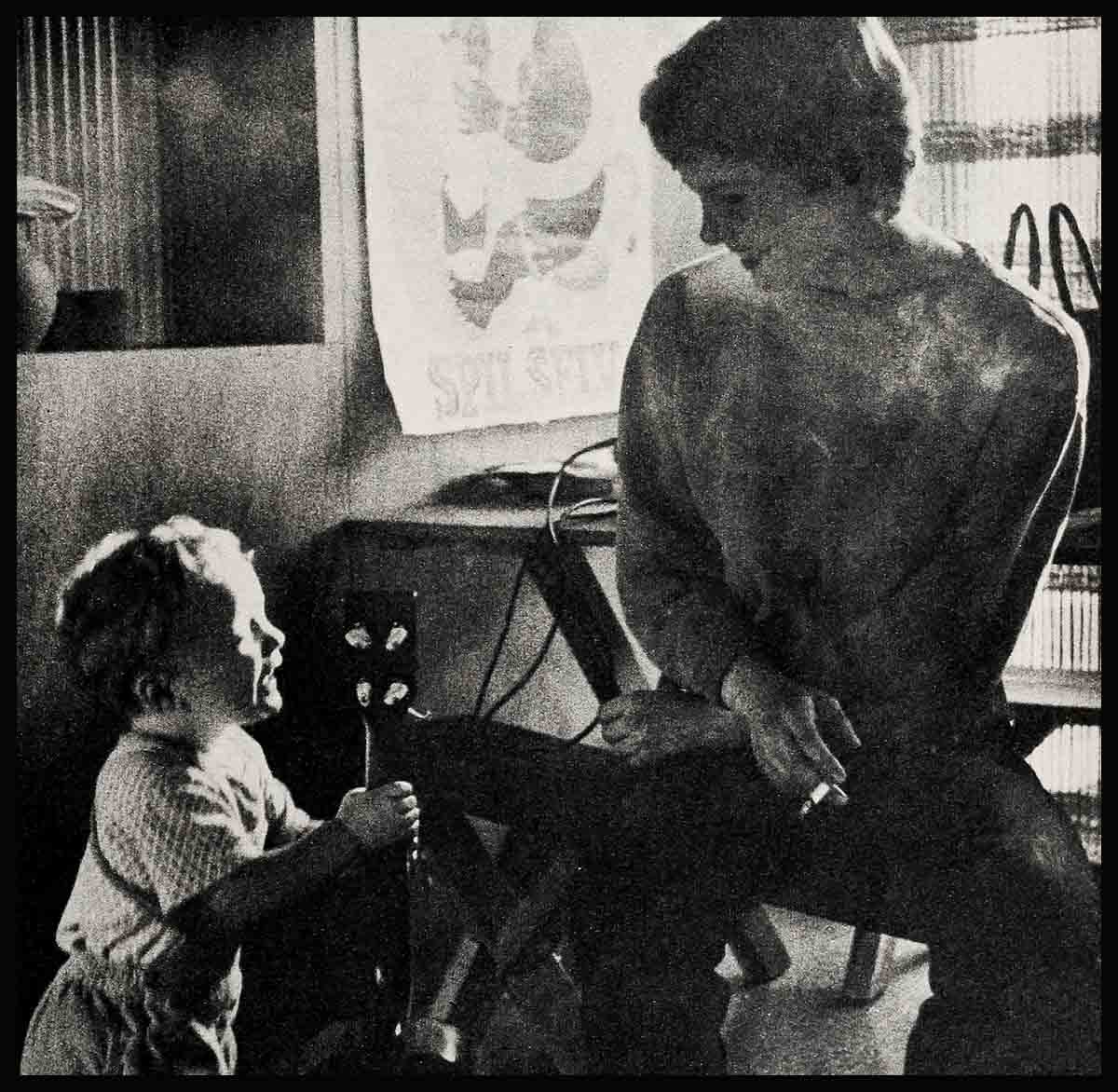

And yet—out of that marriage, so quickly annulled, came the one great joy Diane Varsi has known—the one beloved that no one and nothing can take from her—her son, Shawn.

It was five months before his birth, her husband already gone, that Diane wrote the letter that changed her life. A very simple letter, indeed, to the one person who had never failed her: Dear Grandpa, I want to take acting lessons. So send me some money for them, please. Also, send me some more. Because I’m starving.”

It was not dramatics, just a simple statement of fact. She was down to skin and bones from malnutrition; her face wore blotches of acne from the wrong kind of diet and too little of it. She has vestiges of it left today—carefully hidden under make-up for Peyton Place, just as her cropped hair was hidden under a wig. But when the money came, the dramatic lessons started.

She had gotten interested one night when she went to a Hollywood acting school to pick up a friend. It was challenging, a way of expressing herself—and she had never turned down a dare in her life. She had no particular ideas of a career; movies she despised, glamour she loathed. But acting intrigued her. She started at the school—and quit it, because it reminded her of every other school she had been to: classes to attend, lessons to learn. But she studied by herself until an acting coach named Jeff Corey met her and was stunned by her. He took over her training, told her she was “highly exciting as an actress, amazingly able to act without making it complicated.” And by the time he sent her to her first audition, for the key role in Peyton Place, even Diane admitted “I knew what I was doing.”

Brave words. She meant them—and yet, after the picture had begun, every day she greeted Mark Robson on the set with the same question: “Am I still in the picture?” And she meant those words, too. Something so good could not last.

In January, she filed for her second divorce. This time from a young producer, James T. Dickson. She will not talk yet about how they met, why this marriage too has failed. They were married in November of 1956, shortly after Diane had decided to act. He wanted then to manage her as a folk singer—now he manages her as an actress. More than that about him, no one knows.

And about Diane today, with an Oscar nomination in her pocket, with two more movies behind her and an unlimited number ahead?

Diane today

She still lives in a four-room apartment with just enough sticks of furniture to sleep and sit down on. She gets around town in a ’49 Ford, fast, cutting the corners. She doesn’t own a knick-knack, a luxury, or a decent wardrobe. She has added no jewelry to her one surf-pounded rock. She has not been to one glamour party, and has accepted no invitations for the future. Her health is still shaky, but she’s working to build it up with a diet of fruit, vegetables, juice, raw eggs—and no candy. At home she does body exercises, piles into bed at 9:30 almost every night after two hours of heavy reading. Her friends are obscure people “I meet every day here and there” who sometimes drop in for coffee and talk—and to hear Diane pat her Cuban drums and sing her folk songs. She knows that others gossip about the way she dresses, and she says, “I don’t care. As to the way I live—well, I guess I do some strange things.”

Ask her why she does them now, now when she might live for the first time as other people do, now when she might be surrounded with friends, and she will tell you, “I want simplicity. I want to strip my life down to the essentials.”

But those people in Hollywood who are coming to know Diane Varsi and care about her have another reason to offer. They say that she is still afraid, still lives in fear of growing to love anything, any place, any life too much—because if she does, it will be taken away from her as her mother was, her grandparents, her toys, her curls, her dreams. They say she allows herself nothing so that she can lose nothing. They say she has been hurt too much to try again.

And yet, when they see her bending over her baby, hear her talk of his bright, independent mind, see her eyes light up when he stretches out chubby arms for her—they know that Diane Varsi cannot possibly keep herself from loving. She cannot keep from loving forever. . . .

THE END

You can see Diane in FROM HELL TO TEXAS, 10 NORTH FREDERICK and PEYTON PLACE, all for 20th-Fox.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1958