Little Girl No Longer Lost

“I’ve got a surprise parked outside for you, honey,” said the man, casually tinkering with his watch, more to hide his apprehension than from any interest in the battered, ten-year-old timepiece. “Come on, see what it is.”

The little girl looked up from her piano playing and smiled a little quizzically, a small forced smile. “Oh, Daddy, you didn’t. You shouldn’t have bought me another present. You really didn’t. . . .”

“You bet I did,” he answered hopefully. “Come on, give st a look.”

She smiled back at him, carefully pushed the stool back, making sure she didn’t kick the legs, and just as carefully arranged the music on a pile before she ran over to the window. Looking at her, a stranger would have guessed her to be twelve, maybe just-thirteen, but she was already fifteen; she was fifteen last April 1st.

“A bike,” she brightened for a moment. “A blue bike. It’s—it’s just wonderful.”

“It’s like the one you always wanted when you were back home, remember?” he answered, as though proud of the fact that he still remembered. Then, as if he weren’t sure, he asked hesitantly, “It does make you happy, honey, doesn’t it?”

She started to say something, then hesitated, and, instead, gave her father a hug. “Of course it does, Dad. It really does. I can hardly wait to try it out.’ “Well, go on—go on try it,” he beamed. “You can always finish practicing after supper. Try it out now while it’s still light out.”

She ran down the steps, two at a time, and climbing onto the bicycle waved to her father at the window and pushed off, in what she hoped seemed enthusiasm. Not until she rounded the corner, did she break down and let the sobs and tears come out. Slipping off her bike, she leaned against a building and tried wiping away her tears, thankful that Pico Boulevard was a busy Los Angeles Street and no one would notice her. For how could she ever explain how she felt about the bike she used to want at home . . . about the way things used to be in Portland . . . about the way they were now.

It all seemed so strange, being fifteen, having a big studio like M-G-M sign you up, all this talk about her being a movie star. Any other girl in the world would be wild with delight. Suzanne Burce, so tiny and pretty with such a bright future, knew she should be the happiest, yet she wasn’t. She didn’t want to be renamed Jane Powell; she didn’t care to be a movie star; and what’s more, she didn’t even want to live in Hollywood.

The one thing in the world she wanted most was to go back to Portland, Oregon, where she had always lived and go on with her class into Grant High.

She had to admit Hollywood was fun —for a while. She’d met Clark Gable the other day and Mr. Pasternak, her producer, introduced her to Walter Pidgeon, who’d given her a quick kiss on the forehead. No one could be nicer. But still, when you’re fifteen, you would rather see Larry Karsen, the first boy who’d ever written you a note, saying, “I love you,” or Jack Smith, the first date who had ever taken you to a show, and David Lee, who escorted you to your first formal. David had worn white gloves with his dark blue suit. She was thrilled. The only boy she’d met here in Hollywood was Peter Lawford and he was twenty-five. She didn’t know any girls her own age out here either. She had to go to school on the M-G-M lot. Of course, there was one other pupil, but she was a child. She was only twelve and her name was Elizabeth Taylor and all she was interested in were chipmunks.

“You all right, kid?”

Suzanne looked up, startled, at the policeman in the prowl car.

“Yes, I am. I just got a new bike from my father and I got a little scared,” she fibbed.

“You live around here? Want me to take you home?”

She managed to laugh now, and then the policeman recognized her. “Aren’t you the little girl who was in that picture with Charlie McCarthy? Gaye Stephan was the name, isn’t that it?”

Suzanne didn’t tell him that Gaye Stephan was her last summer’s name. Her newest name was Jane Powell. Neither did she tell him that she wished she could be just plain Suzanne Burce from Portland. But she was polite. “Yes, I am. And I’m fine now,” she answered. “I’ll just wait here another minute and then I know I can ride home all right.”

Home now meant Hollywood. Home was different when it was Portland. It was in Portland that her parents happened to go to a show one Friday night when she was three and, seeing Shirley Temple who was also three, made their decision.

It was 1932 and the depression was on, and they lived in a house so small that it had only one bedroom and she had to sleep in the living room, but just the same her parents found the money to let her take dancing lessons. Four years later they’d managed to scrape up money enough for her to begin singing lessons, despite the fact that the depression was worse and money scarcer for them in 1936. It was happy-making that at seven she got on a local Portland radio show, and it was positively thrilling when, at eleven, she had her own show over station KOIN. Then the war began and she was made Portland’s Victory Girl, which was an important responsibility to her. She went all over the state on Bond drives.

Daddy and Mommy said she mustn’t let any of this go to her head. It was just her good luck and nothing to be concerted about. And she wasn’t. She was terribly, terribly grateful, but what she was really grateful about (though she wouldn’t have told a soul) was that her being on radio and the Victory girl and all that, did make the boys and girls like her better.

Which was really her real ambition—to have everyone love her and eventually be loved by one special boy. Then she d love and marry and live happily ever after with him and their children—five, she thought.

If only Daddy hadn’t had that three-week vacation in the summer and they hadn’t come to Hollywood to sight-see and she hadn’t gone on Hollywood Showcase and sung an aria from “Carmen” and met Janet Gaynor.

Miss Gaynor was the star of Hollywood Showcase and just darling and little. Suzanne had met her first talent scout because of Miss Gaynor’s help, which had led to the Chase and Sanborn show, and then “Song of the Open Road” and “Delightfully Dangerous,” the two pictures in which she’d been known as Gaye Stephan. All that had been fine, because it still was something she could work in during vacation time and didn’t have to leave Portland permanently for.

But now all this—a new name, a contract with M-G-M!—all this meant the end of Portland, the end of all her friendships. . . .

Suzanne wheeled her bike along until she got back to her own Street again. Then she climbed up on it once more and pedaled furiously up to her house. Daddy was standing on the steps, watching for her.

“Go all right, honey?”

“Just wonderful, Daddy, just perfect.”

“Honey, the studio called while you were out. You’re to come in tomorrow for pre-recordings on ‘Holiday in Mexico.’ That’s all right by you, isn’t it?”

“Why wouldn’t it be?”

“I mean, honey, if you’re not quite happy, I bet we could still get out of this—go home.”

She persuaded her father she was happy Five and a half years later, Suzanne-turned-Jane was to remember that moment with poignance. Five years later, as the very newly wed Mrs. Geary Steffen, with five wonderful musical comedies made and released, she received from her father the fantastic news that her mother wanted a divorce.

Her world seemed to rock out of control at that moment. She loved both her parents, but she had to admit that the bond between her and her father was stronger. He had always been her friend, her Champion. He’d never once argued with her—except when she told him she was going to marry Geary Steffen. He hadn’t come out and said so in so many words, but he had implied she was making a mistake, marrying a boy who didn’t know what he wanted to do with his life.

She lost her temper then. Her temper was fiery, always had been, but she’d seldom ever felt a flash of anger against her father. This time she had. She pointed out that Geary had only recently got out of service. She pointed out that he had been a sufficiently expert skater before the war to be in Sonja Henie’s company on tour, but that he didn’t want to go on with skating. She told her father that Geary had many plans, and that they had delayed marrying for several months until he did find some special work, which at the moment was serving as an insurance agent.

But now, here was her father in trouble, turning to her for advice and for comfort, as she had turned to him when she was a little girl.

“I’ll give your mother her freedom,” he said, “since that’s what she wants. But I’m all mixed up, honey. Maybe folks never do know just when things in marriage start going wrong.”

She had turned quickly as he said that, so that he couldn’t see her face. It was like the moment with the bicycle all over again. She was pretending. She was pretending because she, too, was mixed up. She’d been married less than a year, but already she felt something was not quite right.

She kept remembering what Mr. Pasternak, her producer, had said to her when she told him about her marriage plans. “You’re the youngest twenty-one I ever knew, Jane,” he had said. “For all you really know about life you could be ten.”

Yet only a short time later when her mother left California and she’d found an apartment for her father, out in the Valley because he loved the country so much, she forgot all her vague fears. She forgot them in discovering a much bigger happiness: She was going to have her first child.

Now began the really blissful days for her. Just as in her little girlhood, Jane skimmed lightly through her singing, dancing and acting, she concentrated all on this complete symbol of love about to come into her life.

So what if Geary barely noticed the subtle, well-balanced meals she prepared with such loving care? It didn’t matter. Steak and potatoes was his idea of a really great dinner. Coffee and orange juice was a fine breakfast. To Jane, even if she did have to watch her diet like mad, because of being so tiny, food was still one of the major joys of life. But now she went along with Geary on his steak eating.

The baby was what counted. For her son’s sake (for of course her first-born would be a son) she moved, out of that first, small honeymoon apartment she and Geary had. They had chosen it because they could share and share alike in it—each paying half the rent, half the Utilities. Her income would have permitted them to live more lavishly, but then it would be over Geary’s depth financially.

Now they bought an Early American house, such a quaint and pretty place, all spinning wheels and washhand stands changed into jardinieres and the like. Jane brought her son back there from the hospital at the end of July, 1951. Geary Anthony Steffen III, called GA for short.

“Oh, darling,” she said to Geary, “I want our children to grow up in a home brimming with love, joy and security.”

“I do, too,” Geary told her. “And you know what? I’m going into the real-estate business. I think there’s more security there, more future than in insurance.”

It was only a month later that she was offered a series of night-club dates in Florida, New York and points east. It was tremendous money, but it meant being away from her husband and her son.

“Shall I take it?” she asked Geary.

“You’re the boss of your career,” he said. “I’m just boss of our household.”

“But who will look after you and the baby if I go?”

“Look, we’ve got the best baby’s nurse in California. As for me, I can bunk down anywhere. You know that.”

She did know that. He didn’t notice the small “touches” of comfort about their house, any more than he noticed the small “touches” of taste in her meals. It was p nothing against Geary, naturally, any more than her inability to do the sports he did so expertly. He loved to ski, swim and golf. Except for swimming, she wasn’t any good at any of them, try hard as she would.

“Maybe if I appear in night clubs, the studio will get over the idea I’m just a kid,” she said.

Geary grinned at her, his wonderfully winning grin. “Don’t tell me your mind’s not made up already?” he asked.

One month later, when GA was just eight weeks old, she flew to Miami and opened at Copa City. She wore the most abbreviated costumes she’d ever appeared in, she sang jazz as well as opera and she was a smash. But her loneliness nearly tore her apart.

It didn’t help to phone Geary every morning and night, to hear GA coo over the wire. At the end of the fourth day, she said, “I’ve got to quit. I’ve got to come home.”

“Don’t think of it,” Geary said. “We’ll come to you. We’ll be there tomorrow.”

This was the kind of decision for which she adored him. And she appreciated his leaving his work just for her, playing a kind of father-nursemaid just for her.

New York, Miami, the big Eastern cities with their sophistication changed her. She came back to Hollywood with her hair a much lighter shade, with the Peter Pan collars off her dresses and the little girl effects she’d always gone in for completely eliminated. She was twenty-three, a wife and mother. A young matron. She wanted to be treated like a young matron.

She wasn’t. Not by the studio. Not even by Geary, The studio put her in “Small Town Girl,” which to her was a letdown after playing with Fred Astaire in “Royal Wedding.” Of course, it had been an accident that she did “Royal Wedding.” Originally it had been intended for Judy Garland, only Judy got pregnant. Then it was assigned to June Allyson, only June got pregnant, too.

Well, they all three of them had their babies, but from Jane’s point of view, Judy and June had advanced—in every way. Personally, professionally, socially.

Only she and Geary seemed to be doing high-school stuff, skiing, swimming, having parties where everybody played games. Things didn’t seem right. She puzzled over why but never could arrive at an answer. A kind of welcomed answer came when, with the coming of spring, she discovered she was going to have her second baby.

Suzanne Ileen, they named her. Suzanne to remind Jane of herself who used to be, Ileen for her grandmother, Eileen. She was an adorable baby, looking like both Jane and Geary, yet she brought a small shadow of trouble with her.

Just a tiny shadow, yet there it was. Jane, a Protestant, had agreed when she and Geary, a Catholic, were married that the children would be brought up in his religion. Actually Jane hadn’t thought a great deal about it. Like many another of us, she sincerely believed in religious freedom.

Yet now, with the second baby in the house, the difference in the expression of their religions became manifest between the Steffens. They didn’t exactly quarrel over it, any more than they quarreled over food, or sports or house furnishings. They just avoided mentioning these conflicts. And presently, they seemed to be avoiding mentioning many things. In fact, one day Jane shockingly concluded they had very little to say to one another about anything.

Soon after, she was sent on her first loan-out. The studio was Warners. The film was “Three Sailors and a Girl.” The leading man was Gene Nelson.

It was quite natural that she should go to lunch with Gene in the middle of each day’s shooting of the film. It couldn’t have been more innocent. Gene told her about his career on the New York stage. She told him about her career in Portland. Gene told her about how restless he was at Warners. He felt he wasn’t getting anywhere. Jane told him about herself at M-G-M and was amazed, for she too felt she wasn’t getting the right roles. Then one day, during lunch, Gene admitted that things weren’t all bliss at home. Jane held her breath. She’d never told anyone—in fact, she’d hardly admitted it to herself—but she wasn’t happy with the way things were at her home.

Jane mistook this sharing of mutual problems as love; Gene was positive theirs was a lasting love. Gene moved out of his family homestead; Jane told Geary she wasn’t happy.

Jane went into court and secured her divorce. She got custody of her children and Geary got half the community property. But Jane and Gene never married.

Jane moved from the little Early American house to a rather stiff colonial affair which was too big, but it had wonderful play space for her babies. She moved around the rooms of this big, formal house and she, who hated being alone, was alone for the first time in her life.

Her dad came over to see her a lot, but she discovered she didn’t have as many friends as she had always believed, and that those she had were not the ones she had expected to stick.

It was cruel—but it was real—the way her friends had divided into three groups: the ones who had dropped her outright; the ones who told her they disapproved of her but would see her; and the ones who never said a word, either of praise or criticism but who called her constantly, asking her out, chatting to her, cheering her without ever making a reference to the fact that that was exactly what they were trying to do.

There was a fourth group, too—the wolves around Hollywood. Jane shrank from the realization of why they were calling her. This was not what she wanted. It was not what she had ever wanted, any more than she had ever really wanted a career. It was still so tragically simple what she wanted—a husband, a home, children. Anything else was incidental.

She could get through the days with study, with work at the studio, though right then she was between pictures. But the nights were agony. Lying awake through them, she listened to the peaceful breathing of GA and baby Sis, and she knew that above all, she would fight for them to have a normal childhood.

For this, at least, she now knew: If she had gone on to Grant High instead of coming to Hollywood, she would not have mistaken love. At Grant High she would have had scores of flirtations. She would have had time to grow up, to know a flirtation for a flirtation. She wouldn’t have mistaken it for a great love.

To be adolescent in your teens was the way things should be. But to be put in an adult position in your teens, and then to turn adolescent in your twenties, this could be nothing but tragedy.

She got up after one sleepless night and whispered to her reflection in the mirror, “I’m going to try never to hurt anyone again in my whole life. Because now I know what it is to be hurt.”

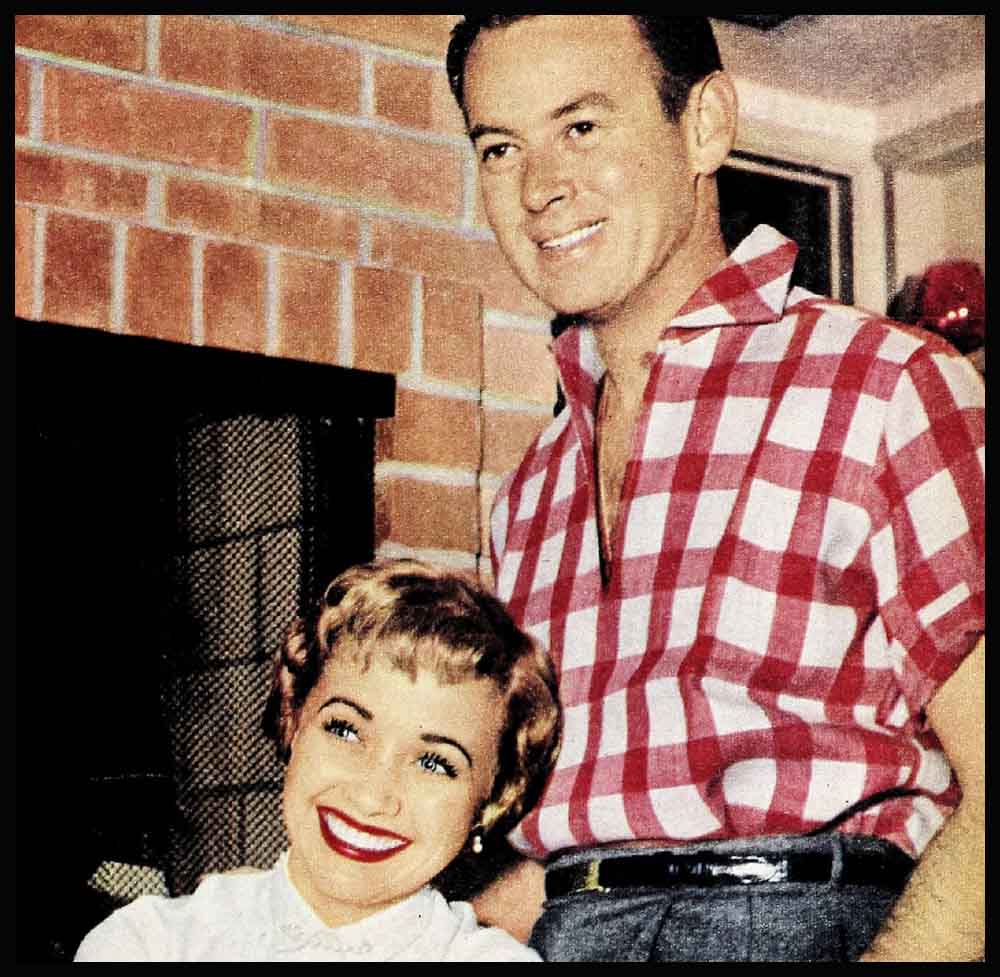

One night Pat Nerney called her for a date and she accepted. She had known him slightly when he was married to Mona Freeman. She had liked him, even though he was a very quiet person, because he reminded her of the businessmen in Portland who had sponsored her career as a little girl. He had the same unassertive security about him, the same nice authority.

–

They didn’t go to a night club on that first date but to a place where the food was superb. Pat didn’t even ask her what she wanted to eat. He just ordered it and it was masterly. He brought her home early and asked if he might call again.

By the end of the week, they’d had three dates. By the end of the second week, he asked her to marry him.

“I’m afraid,” Jane said. “I’m afraid even to think of happiness.”

They continued to date and she was soon fascinated with his talk of paintings, of which she knew nothing, and of books, of which she knew a little.

She began to talk of her interest in music and found he knew as much about it, in a high-brow sort of way, as she did. They got to talking about travel. She’d had a trip to South America. He’s been most places around the world Then they discussed food and wines and children and how to bring them up—his daughter, Monie, age not quite six, was very important to him.

Three nights a week, Pat had to work at the automobile agency he owned with his brother. This meant they couldn’t dine till about 10:30, but Janie loved those nights, particularly, because then Pat would be so full of business details, he’d be unable to change the subject away from them. And Jane saw that he knew just what he wanted to do in a business way. He and his brother were making a fortune, but with all this, Pat’s aesthetic interests were never neglected. He was, she realized with respect and admiration, an intellectual businessman. He was much smarter than she was, much stronger. This she liked, too.

Yet while he again asked her to marry him, she continued to beg off.

Then came the night when he came to her house, as they had previously arranged. It was one of his work nights, so the hour was close to eleven. As she heard his car stop, she put on the hamburgers, a quickie meal they seldom went in for. They were to eat that way this evening because Pat had phoned he wasn’t hungry.

And even as she let him in, she saw that his face looked drawn. She was wearing a little cotton dress and a big cotton mitten on one hand, for handling the hot griddle for the burgers.

“Hurry out into the kitchen,” she said, kissing him lightly.

“No,” Pat said. “You have to answer me something first. I’m going to ask you to I marry me once more. Right now. But this is the last time. Will you marry me, Jane, or shall I stop coming here?”

Her heart thudded. She looked at his face, so suddenly stern. He didn’t say things lightly. This she knew. There were her children to think about. There was her career to think about. But there was nothing to think about, she realized, if she lost Pat.

She stood on tiptoe and put her arms around his neck. “I’ll be so honored to be your wife,” she said.

A year to the day of their first date they were married in Ojai, California. No accident that, of course. November 8th, 1954 it was, and they were off to Paris and all Europe on a honeymoon right after.

When they got back, they moved into a wonderful modern house. Pat’s quite fabulous collection of modern paintings looked terrific in it, but that wasn’t their entire reason for choosing it. Janie wanted it because it was up to date. It was not a playhouse, like Early American or Colonial. It was not flirtatious. It was just plainly I beautiful, practical, livable and a place for growing children.

And for the first time on-screen, too, her studio let her appear, in “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers,” as a mature, intelligent, lively, romantic young woman who completely adored her husband. Type-casting in a way—but wonderful.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1955

graliontorile

21 Haziran 2023It is actually a great and useful piece of information. I am satisfied that you shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.