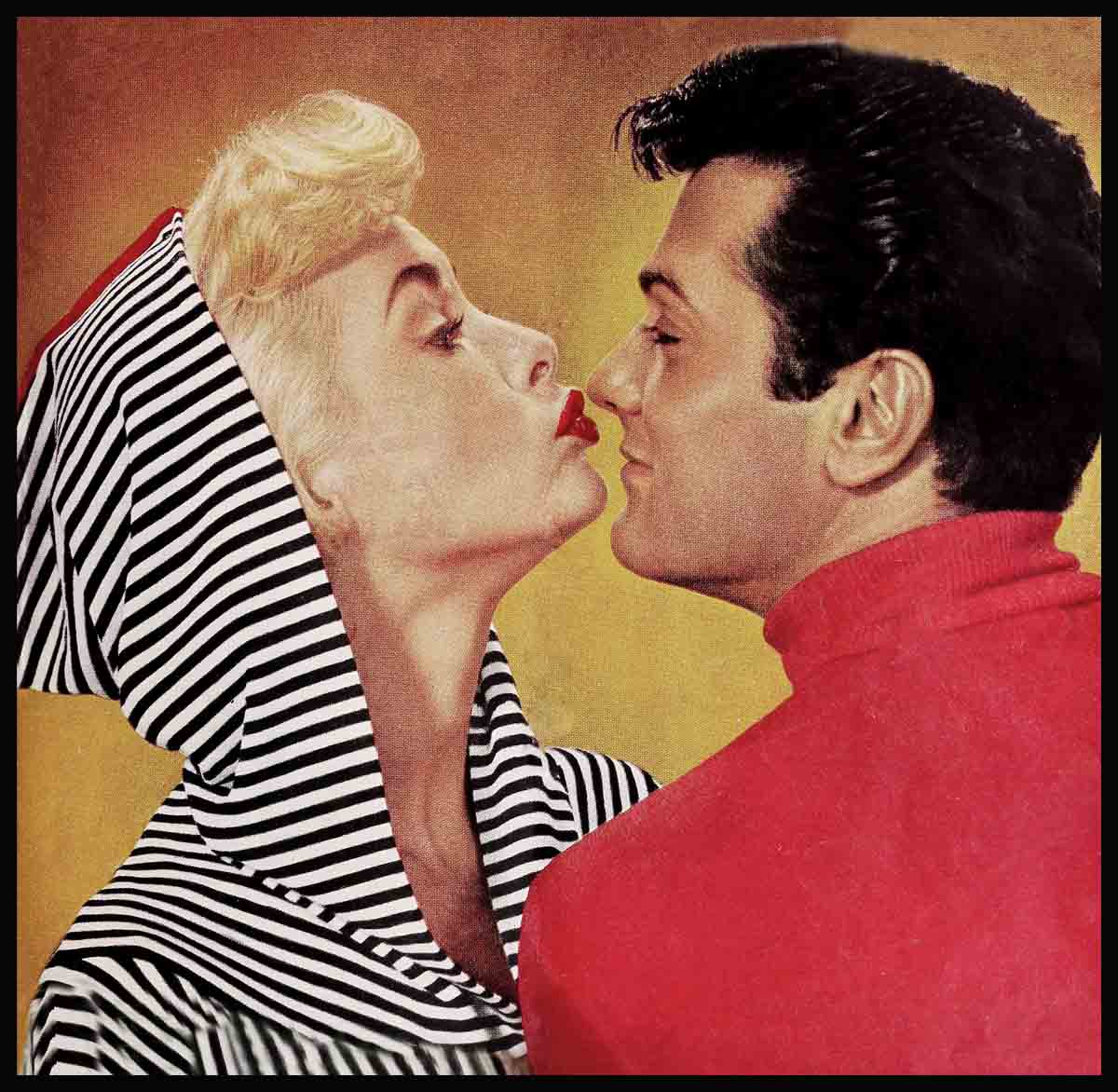

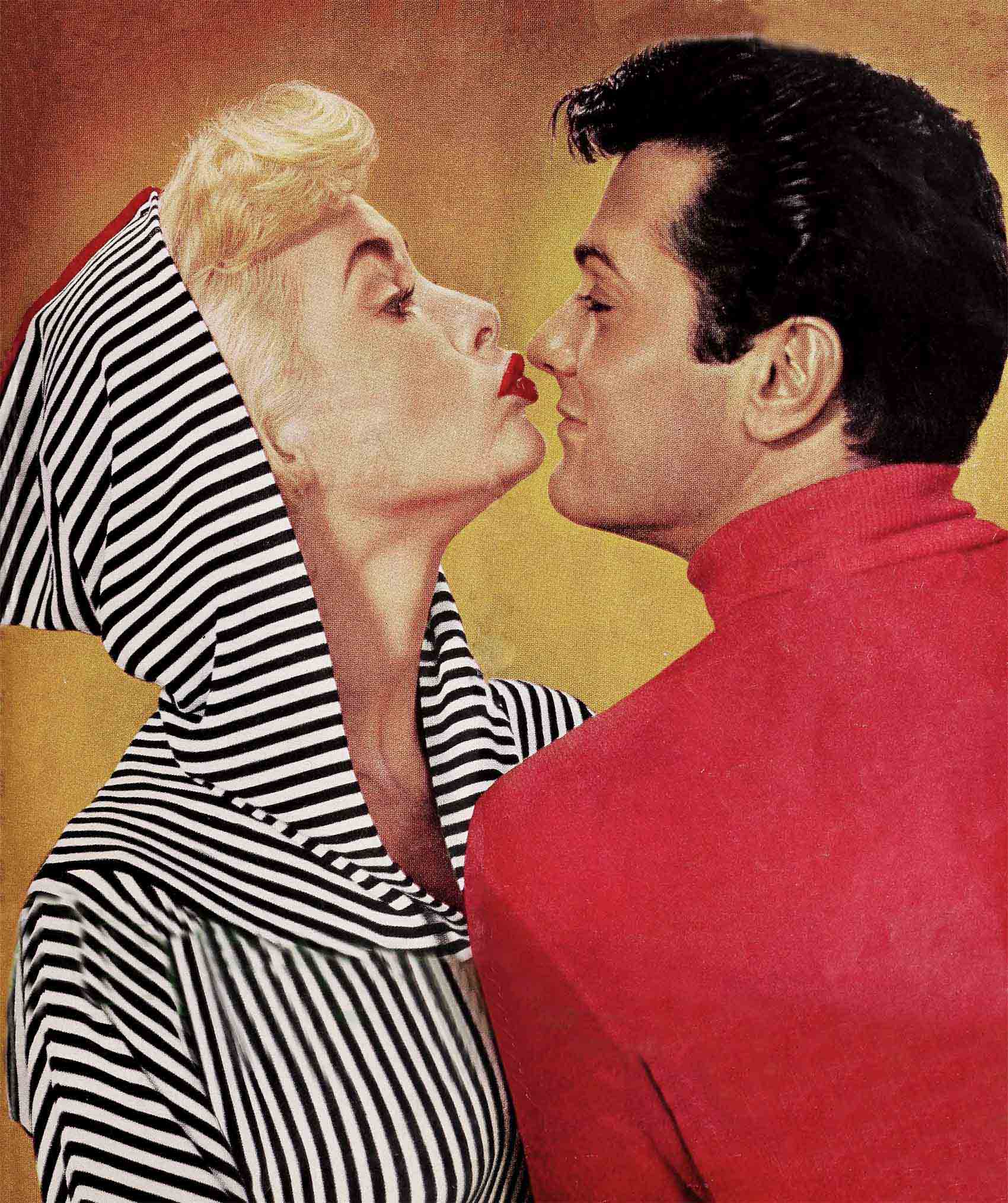

To Janet Leigh With Love

On Christmas trees you hang presents. On this Christmas story I’m hanging a few for Janet. Not the kind you wrap in fancy paper. Or in fancy words either. Mine are wrapped in a plain word. Thanks.

It’s our fourth Christmas together, and the girl has had her headaches. You’ve heard about some of them, but only the half of it. In this case, half a loaf is worse than none. Might create the impression of Craig’s Wife round the house, or Dietitian Mary. Than which nothing could be wronger. Unlike Craig’s, my wife is too straight to finagle. Biggest deal she ever connived against me was four eggs. For my own good, naturally. But we’ll come to that. First, I’d like to go back a little, not to excuse, just to explain myself. And what Janet was up against. And how she operates. Whether by psychology, intuition, horse sense or her own private brew, you name it. All I know is, it works.

Some guys are easier to live with, some harder. Being no worm to bite the dust, I’ll call myself average. Stubborn here, flexible there. Except for a bunch of quirks. Only quirks don’t grow overnight. We’re all conditioned.

I was conditioned to potato pancakes for dinner. Eskimos live on blubber, Chinese on rice, I lived on potato pancakes—with a bottle of cherry soda to wash ’em down. My father had a tailor shop. We never went hungry. Day-old bread wasn’t that stale that you couldn’t chew it. Tomatoes you could buy for a penny at the corner stand. We didn’t know from balanced diets or regular mealtimes. A.M. or P.M., when I felt like eating, I ate. Mornings, a big bowl of coffee, mostly milk, with matzos broken up in it. At school, a hot dog which I paid for and the root beer they threw in free. Plus what I scrounged from my friends, like an apple or cooky left over in their tin boxes. Plus a couple of dirty dried apricots. We’d swipe ’em from wagons and stuff ’em in our pockets for emergency rations. Covered with two weeks’ lint, they tasted fine. But potatoes were the mainstay, and the way my mother cooked pancakes they were also a pleasure. I never felt cheated, I never got sick, I never had so much as a cold when I was a kid. I enjoyed my food. I didn’t know any better than to thrive on it.

So all of a sudden I’m in Hollywood, and what happens? A conspiracy. At Universal they break for lunch on the hour. Okay, I can handle Universal. If I’m not hungry on the hour, I take a walk. If I’m hungry at three, I send out for hamburgers. But the plot thickens, I’m invited to parties where they serve full-course meals. With tidbits yet. Full-course meals destroy my appetite. Tidbits I don’t appreciate. Food is secondary with me. To stay alive, I eat. But the oolala bit with the delicate palate, this I don’t dig. And on top of insulting me with filet mignon, there’s something else. Filet mignon becomes a symbol. They’re forcing their tastes on me, moving in on my idiosyncrasies, tampering with my likes and dislikes. It’s an affront. Nobody’s going to rob me of the things I grew up with, and hooray for my side. Of course I could’ve stayed home with a sardine in the first place. But who wants to be reasonable?

That’s how things stand when I take a bride, God bless her, who’s also conditioned. Only the other way. Three balanced meals a day. Right out of the book. For Janet’s metabolism, it’s great. She likes proteins. I like cherry pie and PepsiCola. She likes to eat by the clock. I like to eat by a very whimsical stomach. This could drive most women ga-ga, but not Janet. Sure, she wants me to eat healthy, but she-won’t press. Hands off is her slogan, she respects my sacred identity. Till a crisis blows up.

My dad gets sick. The job separates me from my brand new wife. I do a Finn-twin. From 150 I drop to 130. I catch my first cold. Aha, I’m falling apart. When Janet sees me, she flips. She starts with the food. To build me up. A wife’s natural anxiety. Who could object? Me.

I say, “Stop with the food!”

She says, “You can’t sustain life on coffee and a doughnut for breakfast.”

I come out with the hokey lines. “Man does not live by bread alone.”

“It helps,” she says, and coaxes me into breakfast. Janet coaxes nice. I swallow one egg, scrambled. She gives me a kiss and tells me she’ll up it to two. Without kissing or telling, the pile grows bigger. I look at the plate, I look at her. “How many eggs in this mishmash?”

She blinks a little. “Four.” I get mad. But under the madness, my funnybone clicks. Here she’s cheating me and I ask her and she tells me the truth. A female George Washington. Somebody else would’ve lied it down to three. Janet’s relieved. It’s even my fault a little. “You should’ve guessed sooner. It was killing me to keep the secret.”

For dinner she dreams up dishes to please me. I turn them down. She’s patient, she’s rational, she’s sweet. “We’ll find out what you like by the process of elimination.” I eliminate everything. I act like a chowderhead. What I don’t know, I won’t eat, even when personally introduced by Janet. I don’t know lamb with mint sauce. I don’t know green jello with carrots inside and mayonnaise on top. You’ve seen this dessert? Or salad? Or foolishness? To me it’s ersatz. If you want carrots, serve carrots. Jello’s for babies. Mayonnaise you can stick right back in the jar and clamp the lid on from here to eternity. Then there’s something called chicken a la king. I don’t even care to hear the name pronounced. So Janet gives me steak. I’d rather have a hot pastrami sandwich, but I’ll do her a favor. A small steak, she says. Only it’s nine inches high. And a nice glass of milk. But I can’t mix milk with meat. More conditioning from the early years. With meat I drink orange soda. But orange soda’s no good for me. Milk’s good for me. Milk has nourishment. Orange soda has bubbles. I push away the milk and the steak together. I dine on halvah. (An overpoweringly sweet candy. Ed.) Janet loses patience, which she should have done long ago. “Eat what you like, Charlie, and if you don’t like it, try living on air.”

When you’re used to being coddled and it stops, your eyes can fly open. Suddenly I see how tough it’s been on Janet. Here’s this lovely girl who should be saving her energy, knocking herself out trying to keep me healthy. For which I should thank her, not fight her. On the set I can’t live with intrigue. At home I can’t live with friction. Not because I’m a wonderful joe with more ideals than the next fellow. Because I’m a peace-lover. It’s the nature of the beast. Also of the beauty, my wife. When you meet Janet halfway, she comes three quarters. What’s compatibility, anyway, but trying?

We talk it over, we compromise, we adjust. I change my ways a bit, she changes hers. If we have meat, we have meat, and no cream sauce over it. I keep my soft-drink cellar. When there’s pie for dessert, everything’s cleared off so the meat doesn’t show, and I drink milk with the pie. Milk and pie go together. Instead of four, I get two eggs for breakfast, and a strange thing happens. I become very concerned. Maybe she doesn’t care; maybe she doesn’t love me any more. I keep hoping she’ll slip me a couple of extra eggs. I want it both ways—my individuality and my wife fussing over me, a very pleasant sensation which I miss. Still I get two eggs. I think maybe I should go starve again. I brood. Till I catch her peeking out of the corner of her eye to see how much I ate. So all right, now she loves me again and I’ll be a good boy. So good, I’ll even try a new dish now and then. Like Welsh rabbit.

Welsh rabbit used to be a bad word to me. I’d see soft, friendly little creatures killed by shotguns, dissected, stuff poured over them and here, take a bite! My stomach turned; it made me literally sick. One day Janet mentioned Welsh rabbit for lunch. I went green. She brought me a cold towel, she held my hand, she waited till the fit passed. Then: “Tony, just what do you think Welsh rabbit is?”

“Let’s change the subject.”

“Tony, it’s cheese. Plain American cheese melted over plain toast!”

“Th—that’s all?”

“That’s all.”

“Where’s the rabbit?”

“In the forest, in a Disney cartoon, never on toast.”

From green, I got real indignant. I like American cheese. If they called it right, I’d have eaten it twelve years ago. But no, they have to call it a bunny from Wales. Just to eat my heart out.

So much for the food department. Now for the house. I can honestly say without fear of contradiction that I’m the world’s sloppiest character, married to the world’s most fastidious girl. The way I feel about rabbits in the diningroom, that’s how she feels about disorder in the house. True, she lives and lets live. Muss it up all you like, as long as you let her straighten it out again. Like I’m lying on the couch, watching TV. “Janet, could I have a glass of water, please?” She puts it on this little table, I take a sip, I watch tv thirty seconds, I reach for the glass, my hand can’t find it, I jump to see if I knocked it off, it’s gone. “Janet, where’s the water?”

“I thought you’d finished.”

She brings another glass, I take a sip, same routine, same thirty seconds, only this time I know I didn’t knock it off. “Janet, will you leave the glass of water alone?”

She gets the point. Now she takes it away, but not so fast as she used to.

I overdo things worse. Though sloppy, I’m clean—you have to make that distinction. I bathe three times a day. I come home from the studio, I change, and wherever I happen to be, I throw. If it lands in the middle of the livingroom, who cares? What’s wrong with a pile of clothes in the livingroom? I don’t even see them. Till my wife starts picking them up. Then I burn. Not because she invades my right to throw. This is a different story altogether. This offends my notion of what’s becoming. It’s not her job to clean up after me. “Janet, for Pete’s sake, will you sit down and rest?”

“Look, I’m not asking you to put them away. For all I care, you can throw them into the pool. And I’ll fish them out. Just don’t resent it when I put them away.”

Appeal to my sense of fairness, and I listen. I make a magnificent gesture. Janet’s allowed to pick up my clothes. More than that, I sometimes pick them up myself. I realize I’m a big boy now and there’s nothing cute about dirty socks in the livingroom. So I stick them in the hamper. Not always. You don’t break the habits of a lifetime overnight. But I try. My wife gives me an A for effort. For accomplishment, I’m worth maybe C minus. Once in a while I get carried away, and wash my own levis. You know how there’s always a beautiful pair that faded just right, and that’s the pair you can’t live without tomorrow. I dump them into the washing-machine, I dump soap. Janet never bats an eyelash. “Enjoy yourself. Play.” Only thing bothers her, they’re still damp in the morning. “Where’re you going in wet pants?” she might ask, but she doesn’t nag. Instead I find on the bed a new pair of levis. With a note “Sorry, darling, I couldn’t buy them faded.”

Which doesn’t mean that everything goes like greased butter. It still upsets me to see her flying round the house after flying round the studio all day. But I’m big about it, I keep my mouth shut. Because, little by little, the light dawned. Especially after a simple exchange of questions. When we moved, she put away clothes and dishes herself. What she couldn’t lift with her own two hands, she supervised. “Why, Janet? We can afford help.”

“And you can afford to have your car washed, Tony. But you’re always out there with the chamois, polishing. Why?”

“I get a bang out of washing cars.”

“The same kind of bang I get out of keeping house.”

That wrapped it up. I saw my wife had a hobby. Like I listen to records, like somebody else takes a steam bath, Janet cleans up. It relaxes her, soothes her, makes her feel good. Should I yap because her hobby’s different from mine? Or spoil it for her by pulling an ugly puss? She lets me fool round with my model submarines, I let her fool round with the house. To merge 100% isn’t necessary. Or advisable. It’s enough to accept. And agree to a normal amount of disagreement.

There was a time when we yessed each other to a fare-thee-well. What Janet liked I had to like, and vice versa. You want to be happy? Share your interests. That was for us. We’d share every silly interest if it killed us. I’d say, “Let’s go grunion hunting.”

She’d light up like the Great White Way. “I’d love to go grunion hunting. Tell me, is it anything like autograph hunting?”

Or she’d ask me to meet her at Sylvia Frostbite’s shower. Well, I could hardly wait! Good old Frostbite. I hadn’t seen good old Frostbite in forty years, why don’t we give her two showers, why don’t we run, not walk, to the nearest Frostbite?

As I’ve mentioned, my wife is an open person. She couldn’t take it. I was getting a little punchy myself without knowing what to do about it. Janet knew. She looked me square in the eye. “Tony, if I never see another grunion, it’ll be too soon.” I fell down with pleasure. And with Janet’s blessing, I stayed home from Frostbite’s shower.

In one sentence she blew away all that phony sweetness-and-light. She cleared the air. Married, we’re still separate people with separate forms of expression. If we share love and the same basic outlook on life, the rest is a bunch of nothing. Our tastes aren’t that precious that they can’t stand a little kicking around. Now Janet says, “Why don’t we put the flower pot here?”

“The hi-fi,” I say, “is no place for a lousy geranium.”

She says, “Very good,” and puts it someplace else. Once I’d have worried about hurting her feelings. She showed me that’s kid stuff.

For her humor, her honesty, her sense of proportion, I’m grateful. And for her warmth. I remember the first time I took her home to dinner. We weren’t engaged or anything. I just took her home as I’d taken other girls who were always welcome. My mother is an outgoing woman, though a little quiet with strangers. My father’s still quieter. So I bring them a movie star. Their backgrounds are poles apart. It could have been awkward. Except with Janet, you can’t be awkward. She’s too natural. Her friendliness bubbles, her laughter infects you, the walls come tumbling down. In five minutes we were just people who liked each other.

Later, after our marriage, my mama done tole me, “From the first night, I hoped she would be your wife.”

I kid her a little. “You’re making it up.”

But she’s very serious. “The heart tells you. And look how it turns out. A girl who takes care of the house, who doesn’t throw money around, who watches to see that you’re happy. Everything a mother dreams for her son, that’s Janet.” The way my mom talks, you’d think she invented my wife.

The longer they know her, the better they love her, and with reason. Janet wears well. She’s a mixture of softness and stamina. Her emotions are easily stirred. At a sad movie she’s a four-handkerchief weeper, and the only girl I know who can cry at a Disney cartoon. But in the clinches, she’s a rock. Her life hasn’t been any bed of roses. Along the way she’s met hardship, disillusion, grief. These are lessons we all learn, and we all react. They can shatter us, frighten us, make us cynical—or the opposite. With Janet, it’s the opposite. They taught her more courage, more wisdom and sympathy. If I seem to be bragging about my wife, I’m not. Just the facts, ma’am, from one who’s in a spot to know.

When my mother and dad got sick at the same time, I was off on location. In the middle of the night Bobby called Janet, and from then on nobody had any problems except to get well. Janet shouldered the rest, went to the hospital, saw that the folks were comfortable, took charge of Bobby. On the phone she told me what happened—without glossing over what I needed to hear, or building it up either. When I got home, she didn’t make any fuss. We both knew how we felt, why pile up the words? But in a hundred quiet ways she spared me. Kept people away from me, laid my clothes out, saw that there was gas in the car, always left five or ten bucks in the clip on the dressing table, just in case. If I wanted to go to the hospital at four in the morning, fine, she didn’t bother me about food and sleep. Every night after work she’d meet me there. If I wanted to talk, talk. If I wanted to keep still, she’d open a book. Her strength and tenderness were like arms around me. For Bambi, an animal story, Janet has tears. For the realities, she has character. And for character there’s never been found any substitute.

On the lighter side, I also like her firmness. Which brings me back to Bobby for a minute. Whether because he’s the baby, whether because Mom lost a son in between, Bobby can twist her round his finger. He doesn’t feel like homework right now, he talks her out of it. Easy. He talks me out of it. Takes him a little longer, but he’ll spare the time. Not Janet. “Why don’t you do it now, Bobby?” And he does it. Of course, I think my brother has a crush on my wife. He’s reached the right age, fourteen, and he shows the signs. Calls her up on arithmetic problems. When I hear Janet say, “Eight’s divided by seven,” I know it’s Bobby. Instead of “Hi!”, he gets real formal with her. “How do you feel this evening, Janet?”—like he’s bowing from the waist. Or he sits in the car with me, he clears his throat. “Janet’s very pretty, isn’t she?” We’re married three and a half years, and all of a sudden Janet’s pretty. It slays me, but I try to act offhand. “You like the way Janet looks?” He goes shy on me, stares out the window. Five minutes later: “Uh—yeah.” I describe this bit to Janet. “Isn’t that sweet?” she coos. Next time they meet, she tells him to do his homework. That’s a gift, too. To make your husband’s brother learn his lessons.

In the last analysis, marriage is companionship. All the words boil down to that. Janet’s my good companion. We both don’t get our kicks from running around, but from being together. Here’s an ideal evening. The fire goes, the music plays, there’s food on the barbecue and friends come in. Never more than six—maybe the Champions, Dick Quine, Blake Edwards, the writer who’s about to turn director, Jeff Chandler when he’s in town, Rosie and Joe Ferrer. A loaf of bread, a jug of wine, and all six beside us in the wilderness, that’s what we call fun. Here’s another ideal evening. The fire goes, the music plays, Janet’s on one couch, I’m on the other, we read, we talk over the day’s work, we plan how to fix the house nice, I massage her neck so she relaxes. Once in a while we play Scrabble. Not very exciting, is it? But excitement isn’t happiness or fulfilment. That’s what my wife gives me. She gives me peace.

And if you want something tangible, I can tell you that too. The hi-fi’s my baby. I planned and designed it. I talked to the guy who was building it, we went over the measurements—so long, so wide.

“Where do you want the TV set?” he asks.

“No TV set, this gismo’s costing enough.”

“Look, there’s a chassis and tube that go with it.”

“Thank you very much, but what’s the joker?”

Well, it seems Miss Leigh called and told him it’s part of the outfit. I go home and find Miss Leigh. “Funny thing happened. Out of a clear sky drops a TV set.”

“Oh?” she deadpans.

“Somebody phoned Bill, he forgot the name.” I pause for effect. “I hate to say so, honey, but he thinks the person who called was a charming girl.”

The charming girl giggles, the charming story spills. Not long before, she’d been on a TV show. Instead of money, she asked for a Fleetwood chassis and tube to fit the hi-fi. If you think I’m thrilled to get it, you’re right. But not half as thrilled as my wife to give it.

So this Christmas I’m hanging presents for Janet. One’s marked: I’LL DRINK MILK. One’s marked: YOU CAN PUT MY RECORDS AWAY BEFORE I STEP ON THEM. One’s marked: I’LL TRY TO MAKE B PLUS FOR NOT THROWING. One’s marked: TAKE THE GLASS AWAY, ONLY BRING IT BACK. There’s a big one marked: YOU CAN EVEN WASH MY CAR IF IT MAKES YOU HAPPY.

On top stands a star, shinier every year. That one’s marked: LOVE.

THE END

—BY TONY CURTIS

(Janet Leigh can now be seen in MGM’s Rogue Cop; Tony Curtis will soon be seen in Universal’s So This Is Paris.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JANUARY 1955