The More The Merrier

Nose to the glass, tired but happy, Dean Martin stood in the hospital corridor weakly eyeing his new-born. His pal, Mack Gray, and Jeanne’s mother were standing, one on each side, for support. The three of them were speechless.

They’d all been so sure it would be a girl. They’d planned naming her “Gina,” Italian for her mom. They’d been so sure. They had no name at all for this husky one.

For instead of the golden-haired, dainty little daughter they’d envisioned, there lay a very virile young man with a mane of black hair, and kicking like the home team really needed that extra point. Gina? He was “Kid Crocetti,” this one. Dean’s chest pressed the glass too. Out of six children, this was the first to look thoroughly like him. He was the spittin’ image of his proud pop, and already a personality in his own right. No namby-pamby name would do.

“He’s ‘Ricci,’ ” Mack Gray said. A regular little character, they all grinned.

Then turning to Jeanne’s mother Dean said, movedly, “That girl of yours gives me nothing but big healthy boys. I hope she won’t be too disappointed.” He was so sure Jeanne had her heart set on a girl. Still, when he told her, “We have a fine baby boy,” he was a little unprepared for her vehement, “Oh no, we don’t!” She was so sure Dean had wanted a daughter.

Actually they both wanted a son all the time. And the son they had, all man. And so they named him Ricci James—“Spelled R-I-C-C-I” they cautioned all who inquired, “After all, you’ve heard of people with sons named Jon—J-O-N, well, this is Ricci, spelled R-I-C-C-I.” As for the James, anyone could understand that, they feel.

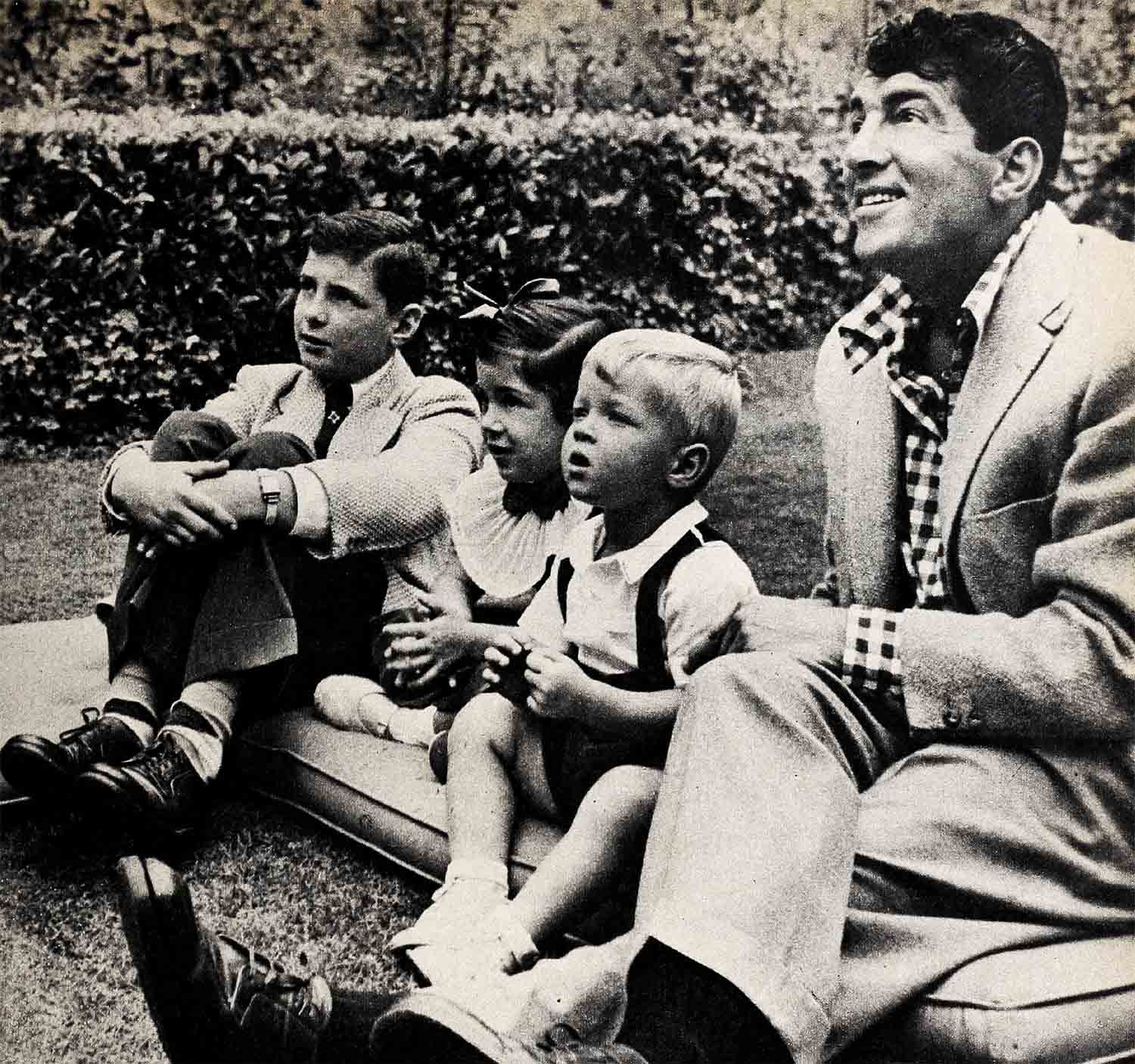

Filing excitedly past the bassinet to see him, the other children—Craig, eleven, Claudia, nine, Gail, eight, Dena, five, and two-year-old Dino—were thoroughly delighted. They’d ordered a baby brother and here he was. No more girls, they’d told Jeanne, being very definite about it, before the baby arrived.

“He’s cute!” his sisters chorused.

“Now we’re even, three and three,” said Craig with relief.

They’re a good group, thought Dean, eyeing them fondly. The four older ones, children by Dean’s first wife, Betty, live in a spacious two-story home two blocks away from the French Colonial place in West Los Angeles shared by Dean and Jeanne and Dino and Ricci—and a great deal of the time by the other children, who are so warmly welcome there. And picking up the tab for all of them, Dino Crocetti, the barber’s son from Steubenville, Ohio, is only grateful and humbly happy that today he can.

The domestic picture of the older Dino, homemaker and family provider, lovingly surrounded by an even half-dozen well-bred children, would have been a shocker for some of the staid citizens of Steubenville, who early predicted that nothing good was in store for him. He was too “racy,” they thought; he was cut out to be a gambler. “And in a way they were right,” Dean says. He certainly wound up with a full house—in fact, two. One thing is sure: he is one of Hollywood’s warmly devoted fathers, this Dean Martin who specializes in laughter and lullabies.

Today all Dean Martin has to do is to look at each of his older children and he remembers vividly the lean days of a few years ago. Of his large brood he says, “Others may swear on their word of honor, but I swear on my children.”

His eldest, freckle-faced Craig, was born when Dean was playing his first professional engagement. “I was singing with Sammy Watkins’ band in Cleveland, and we had it plenty tough trying to meet expenses. I couldn’t raise the hospital bill. Finally I got the money from my father.” Nobody but a gambler would have predicted any kind of a decent future for Dean in those dys.

Dark-eyed Claudia, nine, was born when they went back to Steubenville. “I was working in Walker’s Cafe for forty dollars a week, and my friends kicked in to help pay the hospital bill. Gail, eight, was born in Philadelphia. Money was really scarce then. I was working in New York when I was working, and Betty was staying with her mother in Philadelphia. I couldn’t get a regular job. Everyone thought I was trying to copy Frank Sinatra; I did hold my mike like Sinatra.”

Five-year-old Dena was born in Los Angeles. “I was doing better then. Jerry and I were playing in Slapsie Maxie’s and we only owed a quarter of a million dollars. We were the best-dressed men in town with four suits—law suits—pending.”

When mounting friction and unhappiness strained their relationship past any reconciliation, Dean and Betty dissolved their marriage. And later while playing at a night club in Miami, Dean Martin met the pretty blonde who is now a mother of two sons—and the warm understanding stepmother of Dean’s four older children, who live with their mother just around the corner from them.

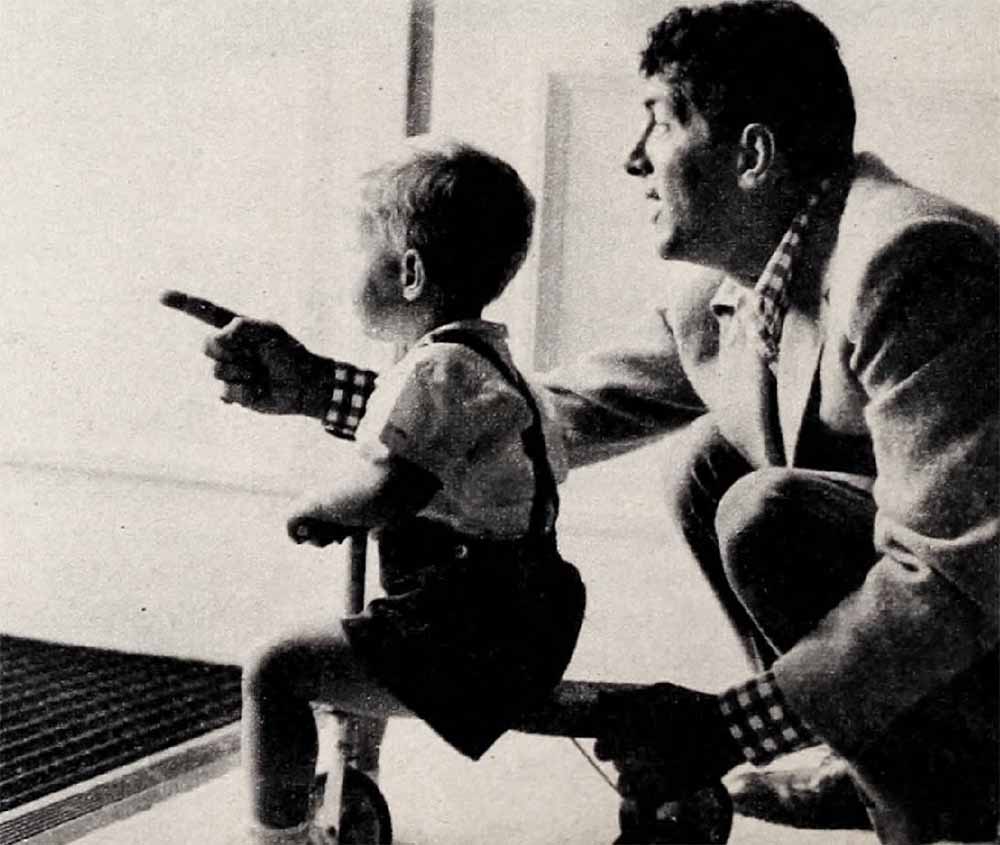

Sunny-haired Dino, Junior, age two, has his mother’s big blue eyes and his dad’s easy-going disposition. “Daddy, sing, Daddy, sing,” he says, which means for someone to start the record player going. Then little Dino pushes the stool over by it, climbs up and listens with his ear as close to the disc as he can get it. And for his pop this is an understandably devastating routine.

Dean’s familiar singing approach when he comes home at night has Dino charging for a first down at the front door. Far from being jealous of Dino, Junior, the older children adore him, and he thinks they are the greatest. Ask them how many brothers and sisters they have and without hesitation they say proudly, “Five.” For now they cut little Ricci in too.

Contrary to what one might think, their home life isn’t confusing. Dean says, “They get real affection and a lot of it. The biggest trouble, I believe, in a broken home is not telling the kids all about it and leaving them to answer their own questions. Craig and I had a long talk when his mother and I separated. He asked questions and I answered them for him.”

For all his pipe-puffing and seeming casualness, Dean Martin is the most concerned of fathers. He long ago thumbed down a swimming pool for either home. This was, in fact, a stipulation in the divorce settlement he signed with his former wife. That she wouldn’t get a house with a pool. “Just too dangerous where there are so many small children,” he says. One of the three times Jeanne’s ever seen her husband angry was when he thought a doctor was too unconcerned about diagnosing what was wrong with the baby. “He got so mad—I thought he was going to pitch him bodily down the stairs.”

A thoughtful and generous father, Dean insists he lays down the law too. “When they’ve needed discipline, they’ve gotten it,” he says. “Such as the time Craig set fire to a window curtain and burned up the whole room. We were living in New York in a little apartment on 105th Street. He was three years old. He was going through a phase then, he wanted to be a fireman—and he was practicing up.”

Asking only that they all remain unspoiled and good little citizens Dean was very pleased to discover recently that at the public school they all attend in the neighborhood, none of them ever tries to impress the other kids. They speak of Dean simply as “my father,” and never spread it around that he’s a movie and television star. A school chum who dropped by the house with Craig one afternoon not long ago stopped in his tracks when he saw Dean. Then, as realization dawned, turned to him with an amazed, “Say—is he your dad?”

“They’re nice kids—all of them,” Dean says warmly now. “Gail’s a talented dancer. Plays the piano well too. Claudia is what you call a ‘Debutante.’ Dena’s only five. She just hangs around—but you know she’s there.”

Neither Dean nor Jeanne see anything extraordinary about both households being so close together. As a matter of fact, as Jeanne says, “That’s one of the reasons we got this place. To be in the same neighborhood. We try to keep close together. It would be too difficult otherwise. Working in pictures, television, radio, and making records, Dean doesn’t have too much time to spend with the family. It’s much more convenient this way.”

“This makes it much easier and nicer,” Dean says. “The children are in and out of here constantly. I see them all the time. Even when I’m working, they’re going to school about the same time I leave the house—and they turn in and have a glass of milk with me.”

While Jeanne takes no credit for them feeling so welcome, saying, “They’re such easy children to have around.” Dean says warmly of her, “She’s the greatest. She plays with them. The girls bring their little girl friends over and ‘try on’ all Jeanne’s lipsticks and sweaters and skirts and model her costume jewelry around. She’s just wonderful with them. And with her it’s no pretense either. She really loves them. Sometimes when she takes them out for a riding lesson they bring a few friends along. One morning there were nine of them. Looked like the whole cavalry.”

The children are Dean’s eager fans and critics. “They tell me what they like and what they don’t. They want to know why I sang such and such a song. Also usually, ‘Did you really kiss that girl?’”

Dean and his eldest share a great camaraderie. He’s had some of the shafts of his golf clubs cut down for Craig to use. “He went around with me the other day at Lakeside and it’s lucky I have insurance. He almost hit a couple of guys.” At radio broadcasts he waves to Craig sitting in the sponsor’s booth, introduces him to the audience, is ambitious for his future. Dean was a little startled recently when he asked Craig what he wanted to be when he grows up and his son said thoughtfully, “I’d like to be a waiter at the Brown Derby.” Relating it now, Dean laughs, “So I told him to just forget the whole thing.”

Despite the fact Martin and Lewis are now starring in a picture called “Living It Up,” Dean insists they’re living it down. In the future we hope not to work as hard. We’re gradually slowing down now. No more night clubs after the date we owe the Copacabana. We’re through playing theatres. No more long tours. That’s my decision. The movies are here, radio’s here television, golf courses, and I want to stay home close to my family.” He’s tired watching them grow up in photographs Jeanne faithfully sends when Martin and Lewis are on tour. “One of my children called me ‘Friend’ the last time out. I got a letter, ‘Dear Friend—How are you?’ ”

Although with today’s responsibilities he can’t slow down too much. “I’ve got to keep working. Don’t ever let them tell you it’s cheaper by the dozen. Take my word for it—they’re not even half right.”

Of the children’s future Dean says, “I just want them to grow up good. And to have security, of course. They’re the reason I’m working. Me, I’m happy if I can just turn the jag in for a new model now and then. They’re well provided for now. Out of the $3,200 monthly alimony Betty gets, the kids have a $1,000 monthly annuity of their own. If she remarries they’ll still have theirs. And they’ll always have a home with their mother or they can come live with us. We’ll always have room.”

Blessed so generously, Dino “Punchy” Crocetti still can’t figure out what he’s done to deserve today. “I’m the luckiest guy this side of East Liverpool.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1954