Notorious Gentleman—Cary Grant

The final shot of “Night and Day” had just been taken. The all-star cast gave a general sigh of pleasure and relief, turned to one another with happy smiles. All of them, that is, except Cary Grant, the topmost star of them all.

Mr. Grant was definitely not happy. His handsome, swarthy face was blacker than a dozen thunderclouds. He stalked over to Michael Curtiz, the director. “Mike, now that the last foot of this film is shot, I want you to know that if I’m chump enough ever to be caught working for you again, you’ll know I’m either broke or I’ve lost my mind,” he said, biting his words out so that his diction was even more flawless than usual. “You may shanghai crews and cameramen to work with you, but no.t me, not again.”

All Mike Curtiz said in response to the Grant outburst was, “Yes, Cary. Yes, Cary.”

With that, Cary walked off the set and drove angrily toward his white brick and black trim Normandy house in Bel-Air.

The doorbell at this house rang cheerfully early the next morning. Since he happened to be downstairs at that moment, Cary personally opened the door.

There stood Mike Curtiz, beaming. In the thick accent, which after thirty-odd years in this country still remains primarily Hungarian, Mike cried out, “Cary, last night I read the most perfect script for us to do together. No story could be as good for you as this one. You have picture commitments that will tie you up through this year. I know that.

But I’ll wait till 1948—or 1949, anytime. Together, we can—”

Mr. Grant pulled himself up so completely that he seemed to gain six inches. “Didn’t you understand me yesterday?” he blazed. “Let me repeat: I’ll never be lunatic enough to play in another of your pictures. Now do you understand me?”

“Yes, Cary. Fine, Cary,” said Curtiz. “But I’ll leave the script.” So he left the script behind him and quietly waited. This was before the trade paper reviews of “Night and Day” appeared. There were so many raves, that the day they came out, Mike Curtiz sent Cary a long telegram of appreciation.

Thereupon Mr. Grant sat himself down and read the script and he’s going to make the picture. With Curtiz; also with the full expectation they’ll row all the way. In the new script, he saw a great picture—and when Cary sees that, walking across red-hot coals to Tibet is a mere stroll in the park to him.

“That’s me,” Cary admits disarmingly. “I raised hell all through the picture—knew it was going to be a flop—so it turns out to be a top success. And as for that Curtiz”—Cary laughs—“There’s a feverish man to work with, but then I’m no dish of weak tea, either. When I cooled off, in between pictures, I knew I was wrong, as usual, and that Mike was right, as usual. The whole truth of the matter was that we had both been after the same objective—to make the best picture we could.”

To make the best possible movies is the end all and be all of the Grant existence. With his divorce from Barbara Hutton final, all the matchmakers of Hollywood are trying their wiliest to get him married to Betty Hensel.

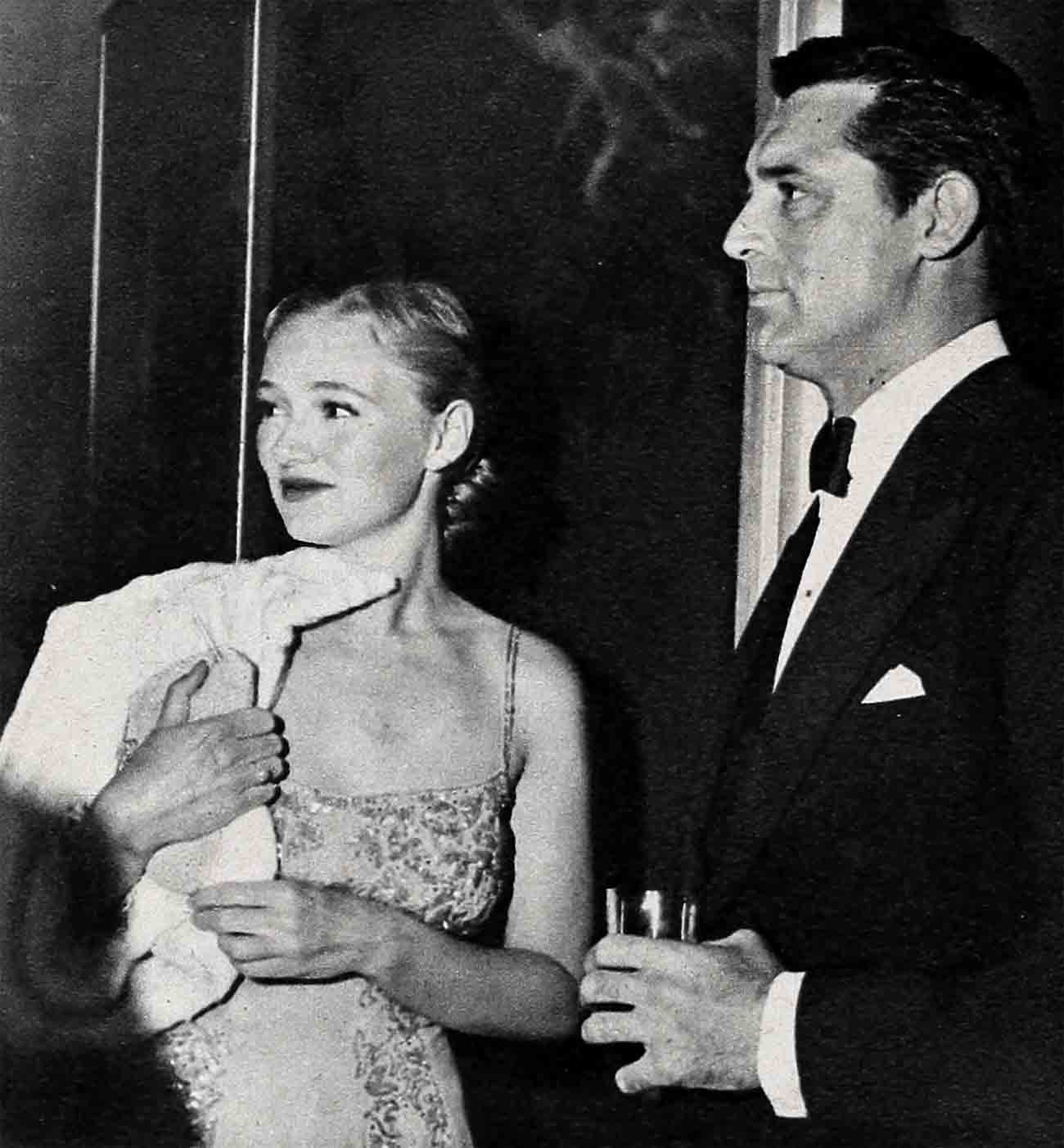

Maybe Betty will become the third Mrs. Grant. Or maybe not. You’ll never find out from Cary. Watch him and Betty dancing together and it’s one of the dreamy sights of this world, her willowy, golden loveliness contrasted to his black height, his sun-mahoganied skin, his intense, intelligent eyes. Cary leads in a manner possible only to the best of dancers, taking one step to a rhythm that from even the smoothest of dancers would ordinarily call for two and from jitterbugs, twenty. It makes him and Betty weave the most sensuous, romantic pattern about any floor. Or watch him at a non-dancing party and he never leaves Betty’s side. He never dates any other charmer even though she sometimes appears with other glamour boys. She is definitely in his tall, chic, thin blonde tradition, that fitted Virginia Cherrill (the first Mrs. Grant) and Barbara Hutton, the second, and has also fitted every other girl he has ever had a second date with. Still, asking Cary what are his and Betty’s plans, gets you no- where. He says, mockingly, “I learned how to duck those questions with Barbara.”

What’s more, that is true. When he knew and trusted you, he used to talk quite freely about Virginia and then “Brooksie”—Phyllis Brooks—when he went around with her. But he clammed up completely on the subject of Barbara from the time of his courtship till today.

It isn’t that Barbara “changed” him. Actually Cary “changes” very little—but Barbara’s influence—and his wish to protect her—did give him a chance to develop his technique of avoiding the personal—something he has always wanted to do.

For instance, the brash, happy-go-lucky character he so often portrays on screen is not the true Archie Leach, who was born in Bristol, England, even though offscreen he often acts in exactly the same way. He can come breezing up to you, apparently overwhelmed with joy because of your mere presence and you may, perhaps, never see him in any other mood. But if you don’t, you see him rarely.

Because his thoughtful, almost melancholy moods are more usual to him than his light-hearted ones. He loves sports and the outdoor life but, nonetheless, he is more a man of the mind than of the body.

When he knows you well enough to be the evolved Archie Leach behind the glittering Cary Grant, he says things like, “The fulfillment of one’s ambitions doesn’t always lead to happiness, but when I started out I was eager to explore the idea that success means happiness. I wasn’t sure, you understand, but I was willing to find out. Now I know that the success is not the happiness. The working is. Working in this profession has given me my greatest happiness. Interested in a role, I escape from myself. In the effort to project a character, any performer has to forget himself. In my case, it lets me get away from my shyness, which I know is a form of inferiority complex, and lets me seem very assured. I’m always happiest when I’m working.”

This is entirely true, and is the sole reason he makes as many pictures as he does. It stands to reason that any star in his income bracket doesn’t need to make more than one or two pictures a year. And beyond a point, Cary has no genuine interest in money.

He has his lavish home; he has a set of perfect and expensive servants, including a very British “gentleman’s gentleman”—and his wardrobe, as absolutely necessary to a male star, holds everything from white tie and tails to numerous lounge suits.

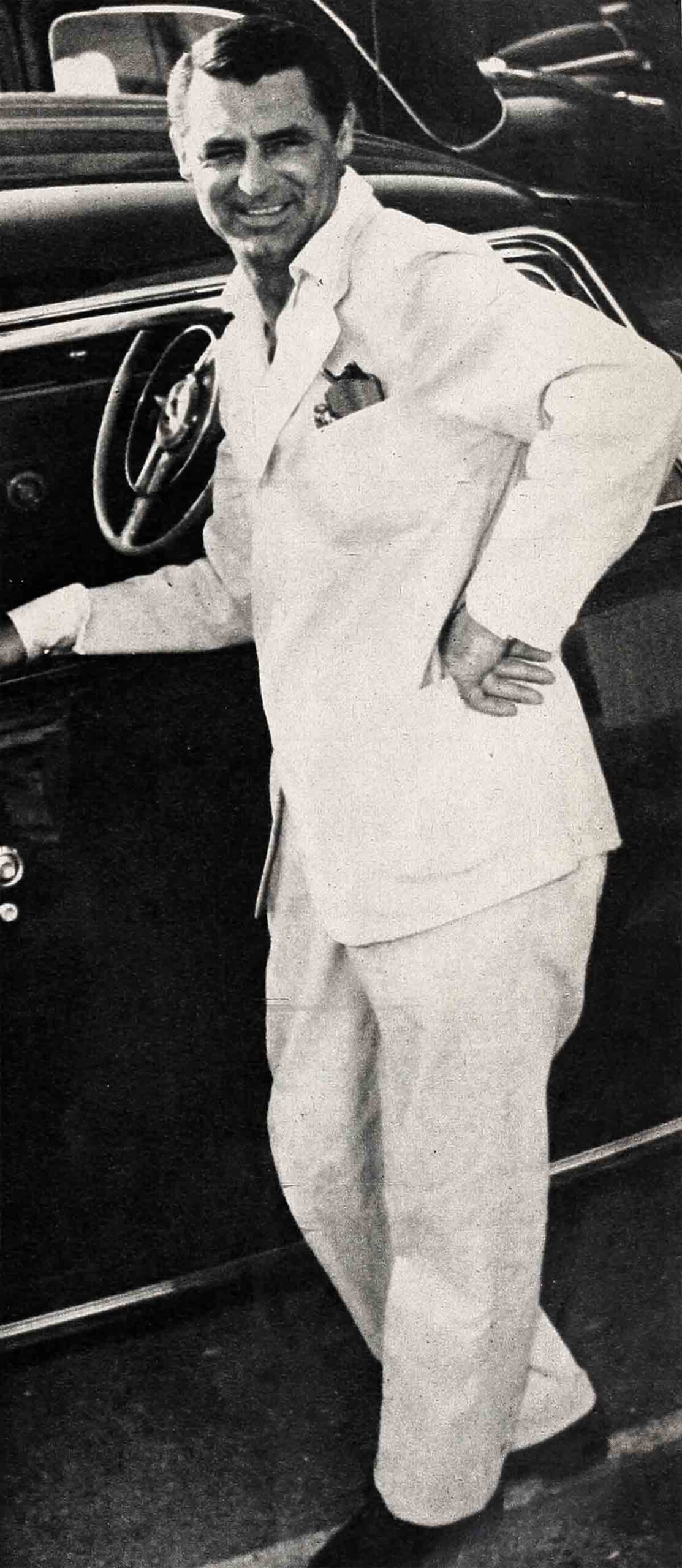

Nevertheless, off screen, he favors seersucker suits which he buys ready-made at a moderately priced store. Even on him, with his broad shoulders and his long limbs, they don’t look very good, but he likes their comfort, their immaculate possibilities—and wears them nonchalantly with custom-tailored shirts that cost triple their purchase price. He seldom wears hats off screen, never wears suspenders or garters and avoids socks while wearing the most spectacularly polished moccasins.

In effect, this means he is all for comfort. He likes to think he is lazy—but he works every minute. He says almost wistful things like, “Do you know anything about Taoism? To me, it’s a worthwhile creed. You just go along with the rhythm of life. It appeals to me because I believe that people and all things should be less active—infinitely more passive.”

He actually believes that he believes this—and then comes on sets and fusses, fusses, fusses.

Right now he is engaged in rewriting the end of “The Bachelor and the Bobby-soxer” which he is making at RKO with Shirley Temple. His current producer, Dore Schary, goes into long huddles with him and lets him rewrite lines one day that he will probably do all anew the next day. Dore is a kindly and wise guy, not at all like Mike Curtiz, and yet his is the same “Yes, Cary. Fine, Cary” technique all over again—which Cary will stay blissfully unaware of until this picture, too, is finished.

Actually, he is very keen about “The Bachelor and the Bobby-soxer” and he collapses with mirth—as do the rest of the cast—when he has to take lessons in jitterbugging from Shirley for some scenes.

His is not temperament in the usual explosive sense. It is rather an infinite—and immediate—capacity for taking pains to make every line, every situation, every “takum” as nearly perfect as possible. If Mike Curtiz was hell on wheels on “Night and Day”—and he was—so was Mr. Grant himself. But it wasn’t because of the fairly common stellar attitude that he wasn’t getting enough footage or sufficient close-ups. Cary has what almost amounts to an obsession about how his lines can be polished—and thus seem more natural.

He is an extremely intense person. There is too much sloppy use of the phrase “a mixed-up guy.” So let us say that Cary isn’t a “mixed-up guy,” but there are two very contrasting sides to his character—and to a great extent they war against each other. Yet perhaps they are what produces the artist in him.

It’s rather like his having run away from home and joined a theatrical troupe because he loved the sea. He wasn’t at all stage struck. He simply wanted to travel anywhere. So he ends up tied to what, for all its glamour, is essentially a country village and because of his fame, unable to move about with any freedom. It’s also characteristic of him that he’s never even considered buying a yacht but before the war, whenever he got the chance, he went to sea on freighters—because that way he got closer to the real lure of vast, watery spaces and further away from people who, on big liners, would have tended to affect his privacy.

EQUALLY, when he travels on land, he is more apt than not to drive himself somewhere in his own moderately priced car and to go visiting small towns rather than the large cities. It completely outrages him that because of the autograph mobs he can’t walk freely about the streets of New York and characteristically, instead of trying to appease these kids, he gives out hot and deeply felt blasts against their rude conduct. Yet in small towns, he’ll stop and chat for hours with garage attendants or lunch-room hamburger slingers. He argues this is because small-town people, even when they recognize him, are always polite and never prying, and are less aggressive than city people.

He thinks he prefers old people. He says, “Whenever I talk to my elders, they teach me something. When they tell of their experiences, no matter how exciting they may have been, they report them in a perfectly passive way—as though they were telling about what happened to someone else. If we could only have adopted this attitude toward our experiences when we were young, think what a lot of grief and confusion we’d have saved ourselves.”

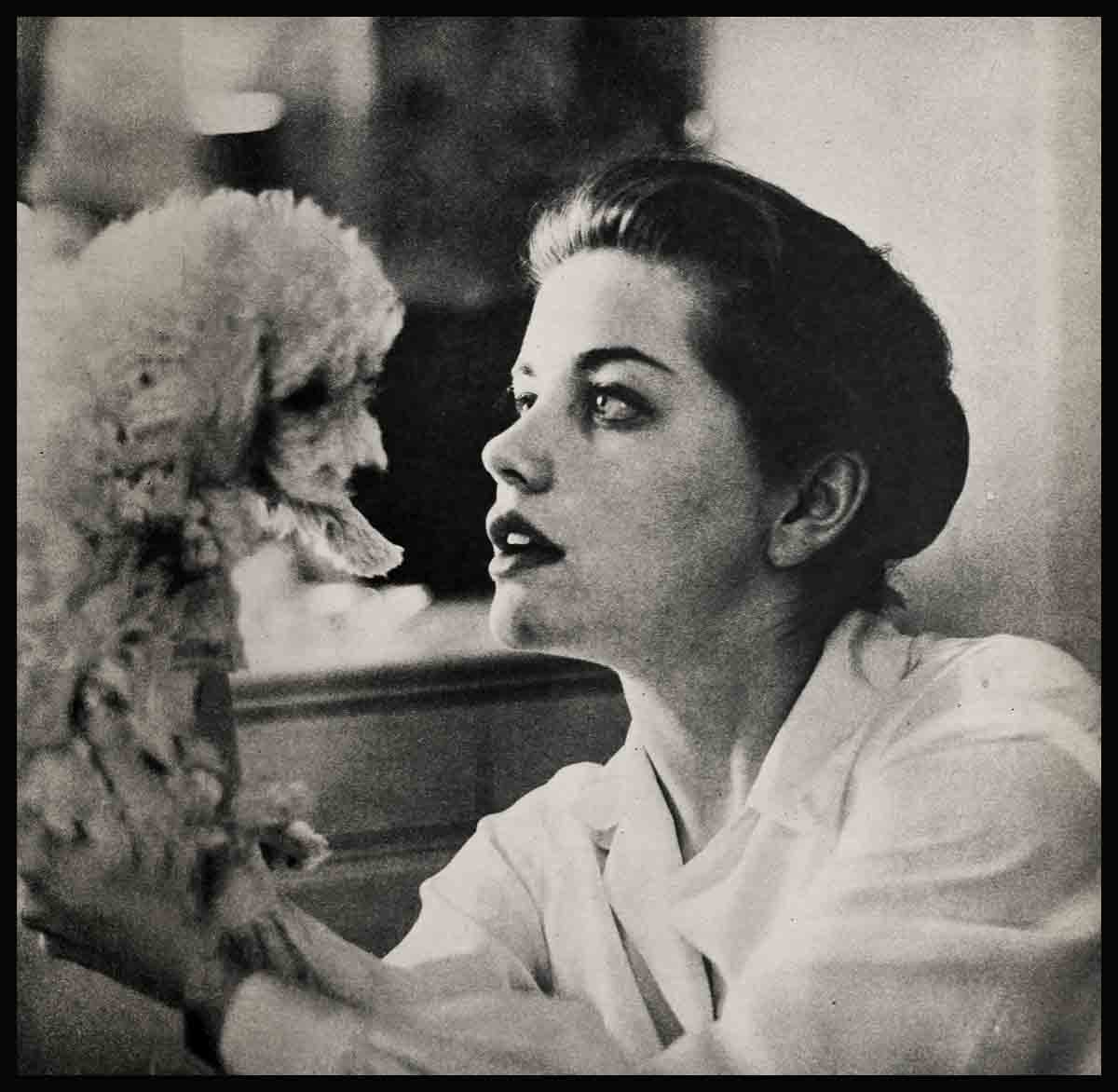

He says that—and yet the three people he most admires are terrific human dynamos—Rosalind Russell, Alfred Hitchcock and Ingrid Bergman. Roz is definitely his favorite woman friend, and he talks to her constantly by telephone. Hitchcock is the one man who can get him into any picture by merely requesting his presence. With any other producer, director or co-star he demands full details, a reading of the script, a knowledge of the cast, the budget and so on. But he went into “Notorious” merely on Hitch’s say-so.

He is absolutely lyric about Bergman, the actress. He is eager to go on the record as saying she is, to him, the greatest artist before the public today. This sweeps all the actors, including himself, off the board—but this doesn’t bother Cary. He is, in fact, one of the few men who regards women as superior in every way. “Innately, in a crisis, a woman is wiser than any man,” he says. “I’ve been very fortunate in knowing many wise women.” That’s what the man says—but obviously he picks his ladies first of all for beauty.

Yes, he’s a contradiction, this Cary Grant—as contradictory as are his Latin looks to his completely English blood—and his passionate love of America. But there are no two ways about his being an artist, a thinker and a gentleman. He’s all that—plus that rare, rare soul who, with continually mounting success, gets steadily more kind and more genuine.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1947

No Comments