The Honeymoon Is Over

“Who am I to talk about marriage?” Paul Newman bristled. “No, I’m not your man. Anyway, I refuse to talk about my marriage for what I consider a very good reason. I have hurt my first wife enough already. I don’t want to hurt her any more!” And with this resounding blast, Paul brought down his own iron curtain around the Woodward-Newman merger. Nobody could blame him. At the former Newman home in Long Island, his ex-wife, Jackie, is tackling the double task of rebuilding her own life and raising the three Newman children—Scott, seven, Susan, five, and Stephanie, three. Paul’s stand was the right thing, the gentlemanly thing to do.

Unfortunately for Mr. Newman’s good intentions, his present wife, Joanne Woodward, walked off with an Academy Award for her performance in “Three Faces of Eve.” And on top of that, he and Joanne scored a joint triumph in 20th’s “The Long, Hot Summer.” all of which has created a public consumed with curiosity about the couple, whether they like it or not. And fortunately for that public, a number of peepholes have developed in the Newman iron curtain—a good many of them made, unwittingly, by Joanne and Paul themselves. Enough of them to form a fascinating picture of what happens when two handsome newlyweds, showered with fame and fortune, come down off Cloud Nine with a thud when they realize the honeymoon is over.

When Joanne was a little girl in Georgia, she says, “I was a great, fat hulk of a thing. I was so self-conscious about it, I couldn’t even speak to boys. So I’d sit in my room, gorging with fudge, and taking refuge in two dreams. In one, I was a beautiful actress in a dazzling gown, sweeping up to the stage with applause ringing in my ears, to be presented with the Academy Award. In the other, I met a handsome man who fell madly in love with me, and we were married.”

The odds against either of those dreams, let alone both, Corning true were so overwhelming that when it actually happened. Joanne still couldn’t quite believe it.

Almost up to the day when, trembling in her new beige chiffon with matching gloves, she sped to Las Vegas to meet and marry Paul Newman, it was a dream that she had fought against, and never dared to hope would become reality.

Ever since they met in 1953, when both were struggling hopefuls on Broadway, getting their first breaks as understudies in “Picnic,” she and Paul had been running away from each other. Subconsciously, from their first long talks that filled the long, heavy hours while they waited backstage. they knew that there was a strong attraction between them. But Paul had a wife and children, and being nice, decent people, they could not take that fact lightly.

When the play closed, there was one mad cross-country chase after another to escape from a force that they feared might become too strong to handle. Joanne rushed to Hollywood, to work in TV shows. But no sooner was Paul signed by Warners for “The Silver Chalice” than she rushed back to New York, But the inevitable happened. Joanne’s performance in a TV show so impressed 20th Century-Fox executives that they signed her to a contract. From then on, with both working in pictures, their paths were bound to cross. still, they tried to avoid each other—until both were cast by 20th in “The Long, Hot Summer,” and they couldn’t help it.

By that time, Paul and his wife had reached the conclusion that, despite all their efforts, there was no way to save their marriage, and a divorce was quietly arranged. still, both he and Joanne wanted to be absolutely sure. When the picture was finished, they parted once more, Joanne returning to her apartment in New York, Paul going to Mexico.

The separation only proved to them what, deep in their hearts, they had known all along—that they were in love, they would always be in love, and they might as well accept the inevitable. So, on January 29th in Las Vegas, one of Joanne’s dreams came true. But no wonder that, even as Paul slipped the platinum-and-diamond wedding—and engagement—rings on her finger and kissed her, she still couldn’t quite believe it.

And the fulfillment of her second dream seemed just as unreal. She hadn’t even wanted to make “Three Faces of Eve.” She’d accepted the part without reading the script, out of desperation after seeing her career languish through many months when the studio was unable to come up with anything suitable for her. She didn’t look at it until she was on her way to Hollywood—and then, she says, “My first reaction was to jump right off that train and go back to New York. It’s hard enough to play one leading role well—but three! It was too much. Then I decided, ‘I’ll go out there and just tell them I refuse to do it.’ ”

Reluctantly, she took the part after much persuasion on the part of the studio, and in spite of—or perhaps because of—one discouraging fact. “I wondered why they asked an unknown like me to play it,” Joanne says drily. “I found out it was because they couldn’t get anybody else they wanted.”

Even after she was nominated for the Oscar, Joanne couldn’t believe she would get it, and stoutly declared, “I don’t care, one way or the other.” A thrifty girl who remembers the days of struggle in New York, when she lived on $60 a month (“It can be done, but I don’t recommend it”), she wasn’t about to invest a lot of money in a gown for the occasion. She made her own, fashioning yards of green satin into a dress as pretty as any “store bought creation.

Then, there she was on the night of nights, sitting beside the man she calls “my beautiful husband,” watching them open the white envelope, hearing her name, walking to the stage with applause ringing in her ears to receive the Oscar. Dream No. 2 came true—for the girl who had tried so hard to run away from both her dreams.

“What’s next, Joanne?” asked a good friend jokingly, at the party after the awards ceremony.

Looking levelly with her big green eyes, at the man who had questioned her, Joanne didn’t hesitate a moment in giving her answer: “A baby.”

The newlywed actress who gushes, “I want lots of babies” has become a Hollywood cliche. But coming from Joanne, it’s a different story, In the first place, she does not indulge in Hollywood cliches. She’s a nonconformist who says exactly what she thinks, let the sacred cows fail where they may. “I know it gets me into a lot of hot water,” she admits, “but how can I have any integrity if I can’t be honest?”

In the second place, a close friend, actress Gaby Rodgers, confides, “Joanne always talked about wanting children.” And another dear friend, play wright Meade Roberts, says, “Joanne has a very maternal nature—to children to her friends To Paul? Extremely so.”

This being the case, Joanne’s desire to put motherhood first in her future is unquestionably genuine. It also effectively squelches the dire predictions some people made. “Of course, Paul’s happy that she got the Oscar,” they said. “But don’t be surprised if it causes some friction later. After all, he’s a good actor, too, and he could feel resentful at Joanne’s winning before he did.”

Paul, the Silent One, is undoubtedly Iaughing up his sleeve at this. When he knows the only role Joanne really wants to play is that of mother, family competition is the last thing he’s worrying about.

But the Newmans do realize that the problem of two careers is one they have to face, now that the honeymoon is over. And they have come to the firm decision: “We will make no more pictures together,” they say.

Their friend, Meade Roberts, explains, “I’m quite sure Joanne and Paul feel that two people who act together are competing with each other, and this isn’t good for a successful marriage. Even in a picture or play, where both were shown to equal advantage, they know that one performance always comes off better than another, and they don’t want that.”

Would Joanne give up acting if Paul wanted her to?

“I doubt if Paul would ever ask her to give it up, says Meade “But if it were really jeopardizing their marriage, she wouldn’t hesitate a minute. Marriage to Paul means more to her than a career. She’s madly in love with him. She absolutely adores him.”

But what about Joanne, who a short time ago confided in an exclusive interview to Photoplay that she really didn’t want to be an actress, because acting had only been a means of solving her childhood problems, and what she really wanted was to become a child psychologist?

“I don’t doubt that Joanne was sincere,” says Meade thoughtfully. “She’s no scatterbrain. In fact, Joanne is one of the most intelligent people I know. Not because she’s my friend and I like her, but because she really is. But I can’t see her giving up the business entirely, because she has an artistic impulse that must be expressed.”

Paul undoubtedly goes along with this. He’s a great one for free artistic expression, and both he and Joanne have made it evident that they want more of the same in the future. They’ve made it no secret that they are chafing under the bonds of their studio contracts, and want out, regardless of the financial security those contracts have provided, and still provide. “I realize things like money and fame have their place,” Paul maintains, “but there are other things more important.”

As soon as Paul finishes “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” at M-G-M, they plan to shake the dust of Hollywood from their feet and return to their true love, New York. They hope to find suitable plays—separate plays-to star in this fall.

They’ve kept an apartment in New York, but, Joanne says, “We’re going to look for a nice, big apartment, with lots of bedrooms, in a quiet section. It has to be near a park, because we want four children!” Anyone who has seen Paul with the children of his former marriage realizes that his feeling for little ones is just as strong as Joanne’s. He lavishes attention and tenderness on Stephanie, Susan and Scotty—named for his idol, F. Scott Fitzgerald—and he and Joanne can hardly wait until the children come to Hollywood to visit them this summer.

With the two big questions of children and careers hurdled, any other problems they have in adjusting to married life will be very minor. As inconsequential as the incident of Joanne and the hats.

“I don’t think Paul had ever seen me in a hat,” Joanne says, “but when we were going on our honeymoon trip to London, I thought I ought to get some, so I went out and bought three. Well, when I got home and put on the first one for Paul, he howled. So I put on the second one—and he went into hysterics. By the time I got to the third one, he was holding his sides, rolling on the floor! But,” she adds with a wicked grin, “I wore them anyway!”

Actually, they have so much in common that it would be hard to see how this marriage could go wrong. Says Meade Roberts, “They’re basically homebodies. They’re both terribly interested in the theater. They have mutual interests in books and music. Paul loves horses, and Joanne now does, too. But, like any two people in love, it’s an emotional thing. Joanne is very emotional. Paul isn’t. He has to lean on somebody. On the other hand, Paul has a rare magnetic quality that draws people to him. Not that Joanne hasn’t, but she loves this quality.”

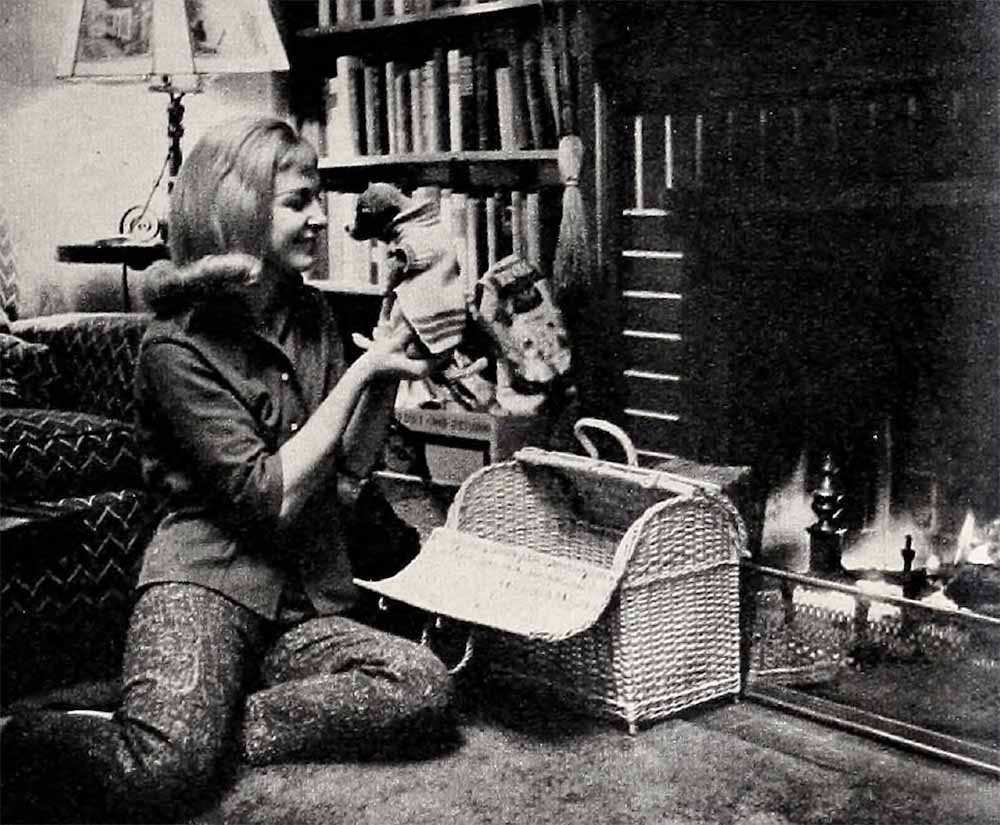

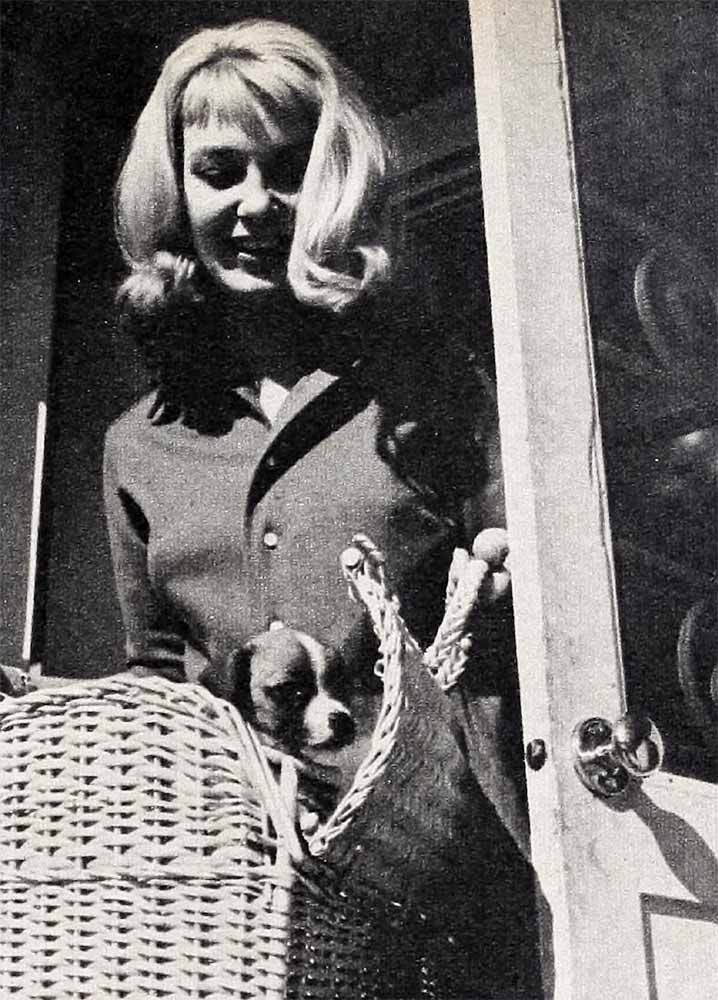

It is this strong, emotional, outgoing quality in Joanne that may prove to be the marriage’s strongest bond. The same way she brings home small, helpless puppies, the same way she has always been the understanding link that made relationships with her own divorced parents smooth, so she can step in to ease the hurts of Paul’s broken marriage and heal his wounds.

Both she and Paul have turned to analysis to help them, and they are the first to admit that it has. They feel that they have gained a maturity and an insight into themselves they didn’t have before.

“I know now,” Joanne says, “that all my big mistakes were of my own making. The wonderful things just happened.”

She confesses that she’s made a lot of high-sounding statements about marriage, which, in the light of experience, are subject to change. There’s one point, however, on which she and Paul stand firm: They believe that when the honeymoon is over, that’s good. Because for them, it isn’t an end, but a beginning.

THE END

JOANNE’S IN 20TH’S “THE BEST OF EVERYTHING.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1958