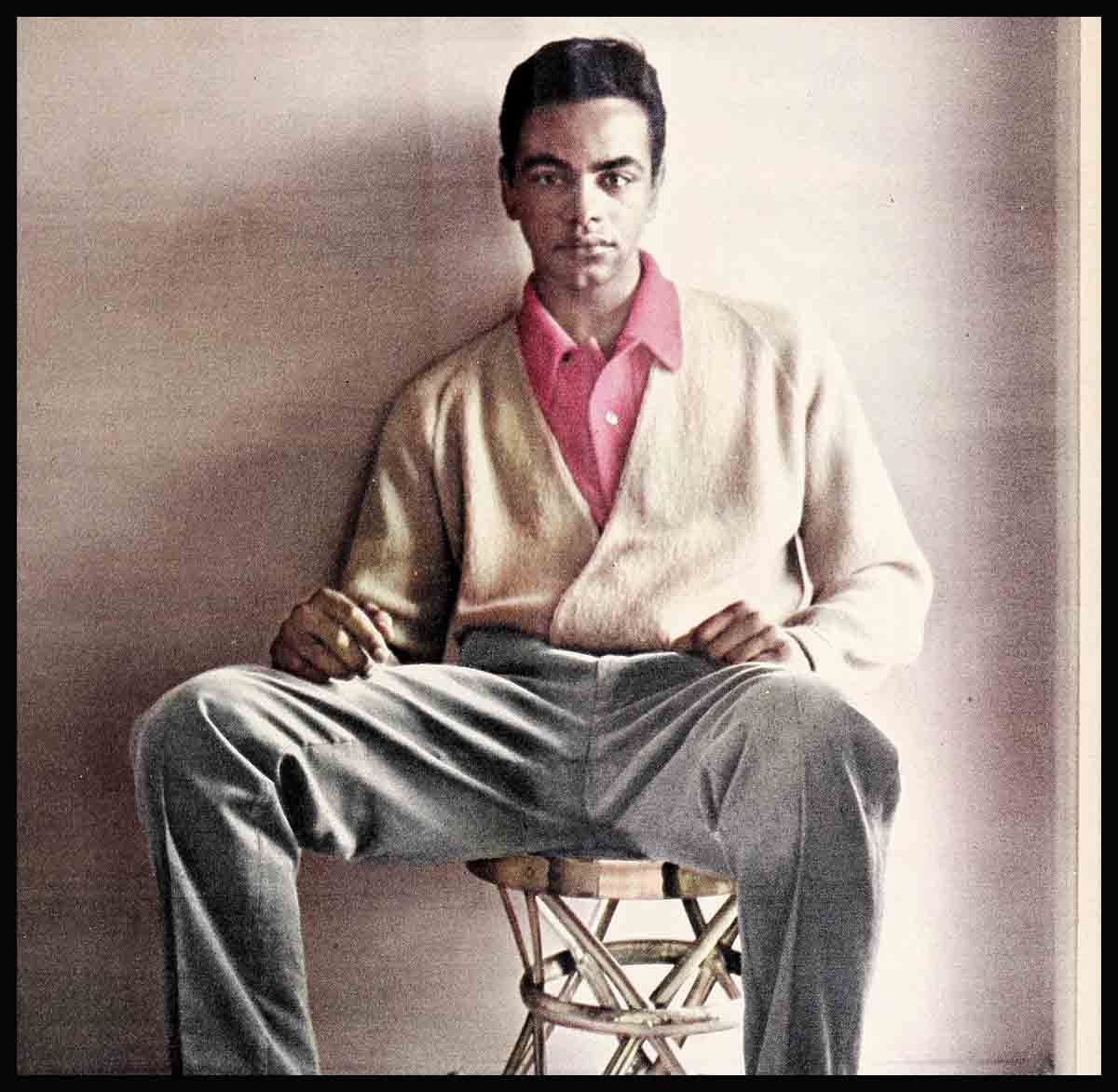

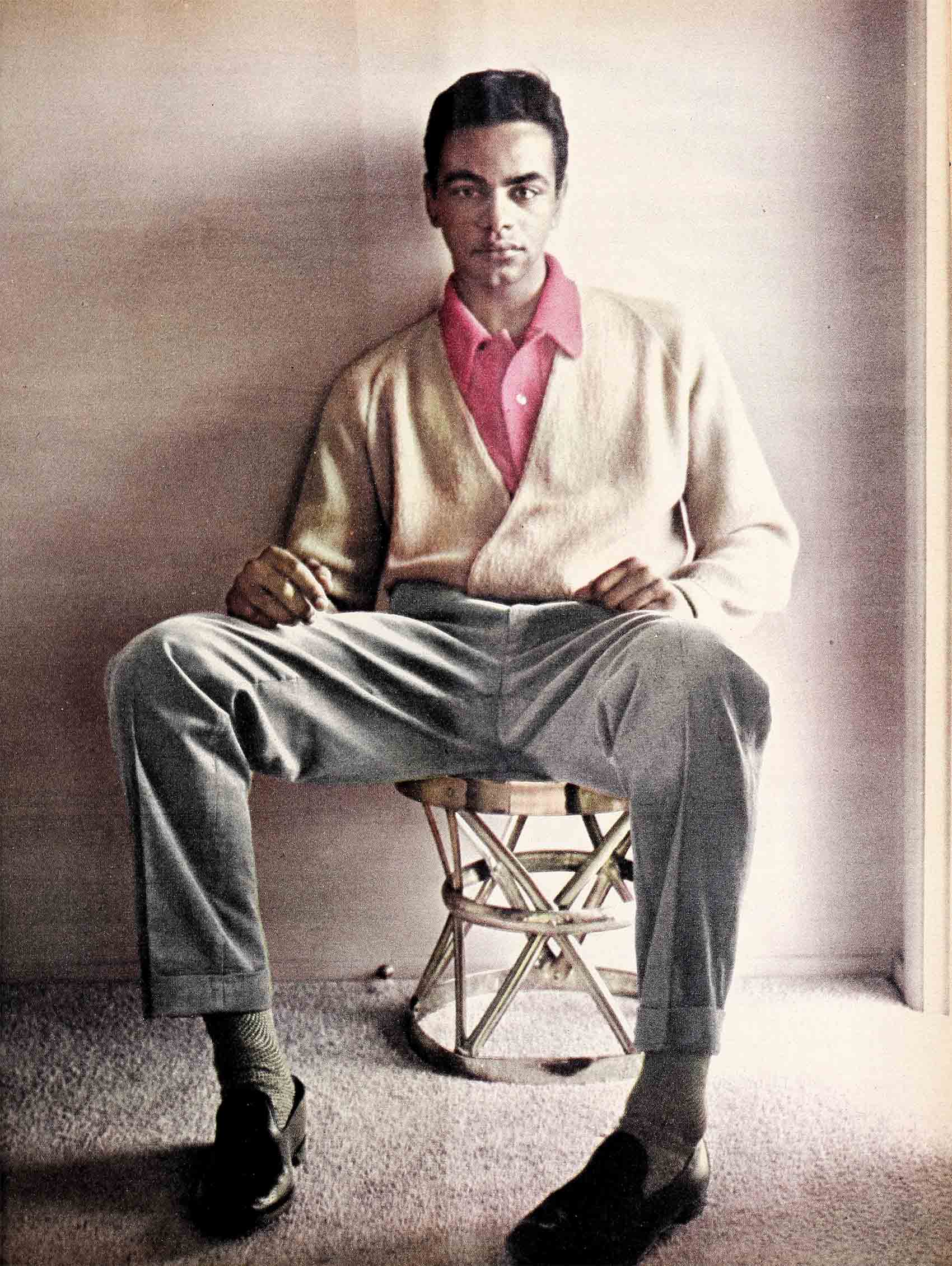

The Invisible Wall—Johnny Mathis

The excited six-year-old patted the old piano as if it were a living thing. He watched with shining dark eyes as his father tugged and grunted and tried to wedge it through the front door of the basement flat on San Francisco’s Post Street.

“Can you get it in, Daddy?” little Johnny Mathis asked anxiously. “How we goin’ to get it in?”

“Well, son,” his dad finally said, “I guess we’ll just have to take it apart.” Clem Lorenzo Mathis had paid twenty-five dollars out of his wages as a painter to get this second-hand piano for his family, and he was going to maneuver it inside that flat one way or another. His young son, raised with affection and care in a neighborhood that was poor yet pleasant and friendly, didn’t realize that any barrier existed to cut him off from a full and satisfying life. Clem knew. He imagined the sweet notes of the piano bringing a bit of richness into his home. But he could never have imagined that for his little boy music would become a gentle yet powerful weapon to smash through all barriers.

Today Johnny Mathis lives in a charming, ten-room, three-story house high up in the Richmond district of San Francisco, overlooking Lincoln Park. It’s handsomely furnished and carpeted throughout in a soft misty green. On the living-room wall hangs the gold record Johnny got from Columbia Records for the first million copies sold of his “Chances Are.” On the mantel is Johnny’s big gold key to his hometown, and near it is the plaque from the mayor of San Francisco, given last December on “Johnny Mathis Day, in recognition of the fine accomplishments of this young man and his attainments in the field of entertainment and fine arts.” It cites Johnny for “being a splendid example for his fellow youth” and “a credit to his beloved city of San Francisco, carrying its name and prestige throughout the United States.”

And in the living room there is a fine new mahogany piano. But “It can never mean as much to me as that battered second-hand piano Dad brought home,” John says today.

“That piano took up half the living room,” Johnny’s mother remembers. “But my husband was determined the children would have a piano—and they did.”

“I carried it into the house a piece at a time,” Clem says. “All the other kids went to bed—but not John. He stayed right there and watched everything. We were pretty late getting it all inside, but I finally got it put back together—and it played. You could see the joy on John’s face! I’d catch him fingering it, and one day I asked him, ‘Would you like to sing?’

“ ‘I’d like to try, Dad,’ the little boy said seriously.”

“Well, I know a song, son,” Clem said. Back home in Texas, he had done a brief stint singing and dancing a soft-shoe routine with what he describes as “a fading minstrel show.” “The song’s called ‘My Blue Heaven.’ I used to sing it, and I’d like to teach it to you.”

Clem played it once and wrote the words down. Almost at a glance, John memorized the whole thing. After that, whenever a visitor dropped in at the flat John’s dad would say, “I have a kid who sings. Would you like to hear him?” Nobody ever had time to answer. With that announcement, John was on.

He’d stand beside the piano, trying to hold his hands right and his back straight and “not droop around,” as his father had taught him. Clem would tell the audience, “Now when John’s through, you give him a big hand.” Then the six-year-old would sway a little to “My Blue Heaven” or “Bye-Bye Blackbird” or, in a childishly sweet voice, “What’ll I Do?”

There Johnny Mathis and his music began, in a block of old flats grown shabby with time and fog and sun. The family of nine lived in four crowded little rooms. Now Johnny says, “You wonder how you did it. We used to always be stepping over things.” There was little money and many mouths to feed. So Johnny’s attractive mother worked as a domestic, and his dad painted or chauffeured or took on occasional contracts for maintenance work.

When Johnny sang, his dad would tell him, “God gave you that. When God gives you a gift, you must be grateful to Him. Pray to Him, and God will give you even greater gifts.”

“And that’s right,” Johnny says quietly. “Everybody’s given a certain amount. What you do with it—that’s the important thing—just doing your best. This was Daddy’s big teaching—to have the horse sense to hear something, learn it, know that it’s true, know how it works, and then go out and practice it. Use it! Don’t just know it.”

Out in the back yard, wash-lines flapping around him, open sky overhead, little Johnny would sing. He’d really give! And the next-door neighbors might become his audience. “Johnny,” kind-faced Mrs. Nebeling would say, “you ought to be in the shows some day.”

“My wife was always encouraging him,” Adam Nebeling tells you now. “She had a soft heart for kids, and Johnny was always singing out there in the back yard. Nice kid—we liked him a lot.”

Minor detail: the Nebelings are white people; the Mathises are colored. It’s a cheerily mixed neighborhood; these days, a Japanese-American runs the corner grocery. Ask Johnny Mathis about the “racial problem” now, and you’ll pretty nearly draw a blank. “I don’t talk about it too much,” he says, “because I don’t like to talk about it. I believe in going out and doing.”

Young Johnny was right in there pitching, as Post Street members. At nine, he was trudging up and down the hill delivering papers. Each weekend, he’d earn three dollars clerking and making deliveries for the Twin Pines Grocery. He was an excellent student and eventually a brilliant athlete, racking up track honors at George Washington High and capturing the high-jump record at San Francisco State.

Mostly, the neighbors remember Johnny Mathis singing. Wherever there was music in San Francisco, there was Johnny. He haunted the balcony at the opera house. When he was older, he hung around Market Street, saw it throb with life when the fleet came in, sang in a tiny bar. On Fillmore Street, he lifted his ardent, increasingly full voice in hymns at the Methodist church.

When Johnny was twelve, his father took him to see a booking agent in Oakland, and the agent said, “He’s pretty good, but he needs some training.”

On this man’s advice, Johnny and his dad went to see voice coach Connie Cox. But her fee was five dollars a lesson, and the Mathises could barely manage to pay the toll charge back and forth across the Oakland Bay Bridge. “I have five other children,” Clem Mathis said sadly. “I just can’t do it.”

“Well . . .” Connie said. “Let me hear him sing.” She listened, and then she said, “You bring him back. We’ll work something out.”

By way of paying for his lessons, Johnny cleaned the studio. “Connie had a tremendous amount of patience,” he says. “She really worked with me. At times I’d get upset—when I couldn’t do what I wanted to—and I’d end up bawling my eyes out. ‘Come on!’ she’d say. ‘That’s no way to act!’ And I’d tell her, ‘You’re a soprano—you can do it. But I’m a tenor—and I can’t do it’ But she kept on insisting that I could.”

Johnny Mathis sang wherever he dared—on any stage, in any spotlight, with any piano or saxophone that would back him, for any band or proprietor that would let him do a number for free. “Nobody dreamed I’d do anything then,” he says. “We were just sort of going along. After I got to singing for money, sometimes somebody would say, ‘Well, kid, you’ll make it some day.’ I was like fourth act on the bill. I’d run out and do my two songs—sometimes three.

“I’ll never forget my first professional engagement. A friend of mine on the track team at San Francisco State had a buddy who had a bar on Broadway. ‘Come on down,’ he said, ‘they’ll pay you to sing on weekends.’ I went down, and it was an old bar with sawdust on the floor. But they had a microphone and a fellow playing the piano—so I sang. The guy paid me fifty dollars for two nights—which was good,” Johnny says. In all that noise nobody even heard him, and the music Johnny Mathis made was not for the sawdust trade. “I did ‘Tenderly’ and ‘Flamingo.’ And I was doing a real fancy thing, where I’d skip octaves and hit the high notes softly, really reaching out.”

One night, Ann Dee who owned Ann’s 440 Club across the street, dropped over to pay her respects—and fairly flipped over him. “Johnny was singing and nobody was listening,” Ann says. “When I heard that sweet lyric voice, I couldn’t believe it. “This isn’t possible!’ I said.”

Another minor detail: Ann Dee is white. Clem Mathis says, “Johnny has had a lot of help from white people. You read the newspapers, and you feel that all the people in the world are bad. All the race troubles in the world confuse a person so that he thinks everybody hates everybody else. But this isn’t true. If Johnny had had hatred in his heart to begin with, he never would have gotten help.”

Instead, Johnny had been raised in a sincerely religious tradition of love. So he got help—and, beyond that, wholehearted encouragement.

Ann Dee introduced herself to Johnny when he was through singing. “Do you know what you have?” she asked. “If you ever need a job, see me.”

Ann Dee had been in show business for thirty years, and she’d coached opera. She’s quick to tell you, “Johnny’s success today is no accident—he could always sing.”

One June night three years ago, a slender young singer came through the black velvet background of Ann’s 440 Club in to a bright spotlight—and a future far beyond the imagination of the kid from Post Street.

Johnny Mathis had already connected with the fighting loyalty and the representation that soon made him famous. “I’d popped into The Black Hawk Club for one of their afternoon jam sessions,” he recalls. “A friend of mine, Virgil Gonzales, was jamming there, and he said, ‘Come on, Johnny, sing a song.’ As usual, I jumped up and sang.”

The proprietor’s wife, Helen Noga, was in the club, and couldn’t believe what she heard. “I heard a young kid singing ‘Tenderly.’ I heard him hitting the high notes and keep on hitting them. I thought, ‘Well, he’ll never get to the top.’ But he did. He hit high ‘C’. I’ve always liked kids, and he was an amazing talent. And I said, ‘This is it!’ ”

Yes, the Nogas are white people. Clem Mathis says of Helen, “My son wouldn’t be where he is now if it hadn’t been for her. She has been wonderful to Johnny—and wonderful for him.”

“Who’s got you?” Helen asked that first evening.

“Nobody,” Johnny said.

“Well, get your mother and father—and I’ll take you,” she said. She says now, “It never even occurred to me for one minute that Johnny wouldn’t make it, that he would ever be anything but a star.”

She told him, “Keep singing here, and I’ll see if I can bring somebody around to help you.” One day Johnny Mathis got a call from her. “I’m going to bring a recording executive over to hear you,” she said.

As Johnny recalls now, “I said, ‘Fine.’ I was very uninterested—because things like that had happened to me before. People would say, ‘I’m bringing somebody in’—and nobody ever came.”

But Helen Noga brought in George Avakian, director of popular albums for Columbia Records. “I remember,” Johnny says, “George had poison oak all over him. He’d come out here for a visit with his sister and got to roaming in the hills and he had poison oak all over his body. It was a hot sticky night, and he was there in that little close club with smoke all over the place—and he was really suffering He only had the heart to hear one tune—he was dying. I sang ‘Tenderly’—again—and I saw him leave, and I said, ‘Well, that’s it.’ ”

Then Helen surprised him with “We’re in!”

Johnny just looked at her. “What?” he said.

“We’re in—we’ve made it,” she said. One number was enough. Columbia Records wanted to sign him to a two-year contract.

That night when he got back to the flat on Post Street, Johnny Mathis waked his dad. “There’s a man I’d like for you to meet, Daddy.”

“Why? What’s his story?”

“He wants to sign me up for a recording company!”

“Was he sober?” Clem Mathis asked.

“Sober as a jury,” his son assured him.

Clem said he’d have to weigh the whole matter. “But Daddy, Mr. Avakian’s got to go back to New York. He’s a very busy man.”

“Before you sign a contract there are a lot of angles to be considered,” his dad said seriously. “I’ve got to think about this awhile.”

As Clem Mathis says now, “I prayed for the right answer—I didn’t know what to do. I kind of searched myself and I asked God to guide me. It meant Johnny leaving school, and I’d had a brief stint in show business and I knew it was a slippery business. You’re never secure.”

These were moments when Clem wondered whether it had been such a great idea to buy that second-hand piano. He’d wanted John to be able to sing, but to make this his whole life? Clem didn’t know.

Six long months went by. One night Johnny Mathis looked out into 440’s black-velveted room—and met the eyes of Lena Horne. “I saw this lovely face peering out of the audience, and my knees started shaking,” Johnny recalls. “But she was just fabulous.” Lena sent him a note backstage and invited him to come to her suite at the Fairmont and have coffee with her and her family. And she gave him the best of advice. “Lena told me it took hard work and just common ordinary sweat,” Johnny Mathis says now.

Johnny Mathis was sweating then. He was singing his heart out in club after club. He worked at a series of clubs with names like the Gaydoll, the Hollow Egg, the Hungry I and the Fallen Angel.

Finally Johnny saw one face he wanted to see most. George Avakian had come to the Coast to record new Louis Armstrong numbers, and he dropped by to catch Johnny’s show. “Well, I think you’re ready to record,” he told him.

The first Mathis records, a jazz album, didn’t get off the ground. A couple of people told Helen Noga, now John’s manager, that he wasn’t ready and advised her to take him back home. She advised them in firm language that he was staying in New York.

Johnny was standing on the corner of Broadway one day with some friends when he met the fellow who would write “Chances Are.” “Somebody said, ‘There’s Bob Allen, the guy who wrote all those hits for the Four Lads’—and I was introduced to him. I felt in a good mood that day and I said, ‘Why don’t you write me a hit song?’ He said, ‘All right, I will’

“Bob wrote ‘It’s Not for Me to Say,’ and he came in one day and said, ‘Here it is,’ and handed it to me. I remember I said, ‘This little simple song? It will never do anything!’ ” Johnny smiles at that now.

However, he recorded it, along with “Wonderful, Wonderful,” which is Johnny’s favorite of all the songs he’s done, “because,” he says, “it sounded so pure to me and I had such good thoughts when I was making this record and I loved the song so much.”

For months the record didn’t move. As Johnny says, “It just lay there. Then suddenly it started to pick up after everybody had given up hope. Then we did ‘Chances Are.’ ”

And then it happened. The barrier was no longer there. As Joshua’s trumpet blasted the walls of Jericho, a sweet singing voice shattered the wall of poverty and ignorance that might have kept Johnny Mathis from using the gift God gave him. He is now a top recording artist, who can handle just about any type of music. He’s a television star. The Sands Hotel in Las Vegas took him on for songs—but hardly for a song. For a fabulous amount! And he’s featured in his first movie, 20th’s “A Certain Smile.”

People who hear him sing—strangers turned into friends by his music—write and tell him, “When we see you, when we look at you and listen to you, we don’t think of you as colored or white or anything. We just think of you as a human being, a person, a typical American boy.” And that makes Johnny very happy.

His dad says, “Soapbox speeches don’t help, to my way of thinking. If you practice fair play, people see you and they respect you. In fact, they have to. They respect what you stand for and what you do.”

True to his upbringing, Johnny echoes the thought. Reminded that he is in a position to do a great deal of good for his people, he says quietly, “Yes, I know. I feel it deep in my heart. I want to. But maybe I can do it better if I just be—doing and performing as well as I know how.”

THE END

—BY DIANE SCOTT

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1958

No Comments