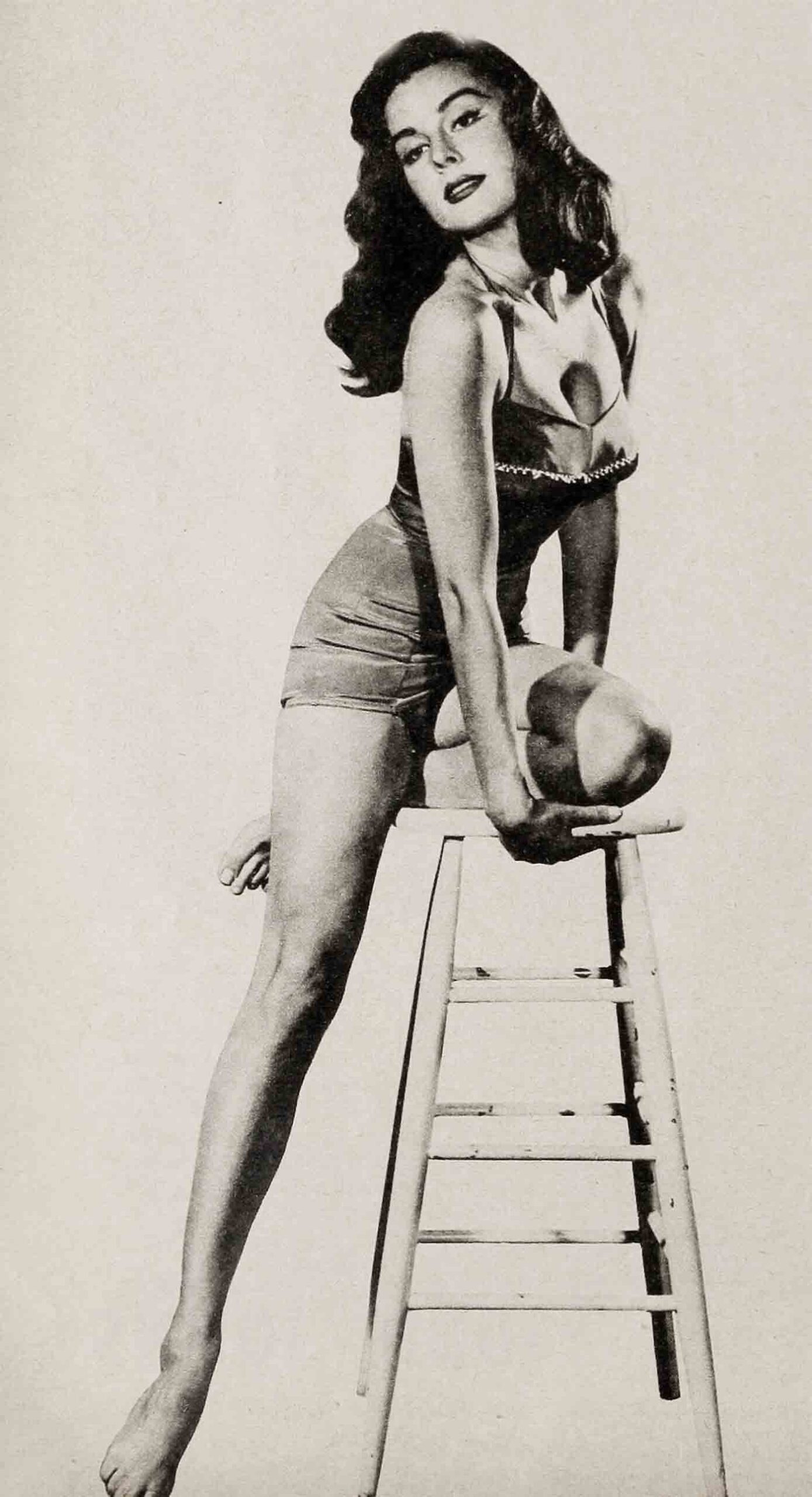

Get Lost, Cupid!—Elaine Stewart

Describing her role in an early picture (A Slight Case Of Larceny) Elaine Stewart says, “I fall in love with Mickey Rooney—but not for long.” And she sighs thankfully.

Elaine means to cast no reflection on Mickey. She’s just shunning the state of emotional bondage known as love. She wants no part of it right now. not even the faintest ache. Serving tea the other afternoon, she remarked, “Marriage—that’s all I need! Just as my career is getting started! Please! Let me have just a couple of years as I am.”

She was holding a new brown teapot as she said this—holding it fondly. She loves the teapot as she loves everything about her one-flight up, one-bedroom apartment: its random layout, the warm walnut furniture pieces, the gay prints on the wainscoted walls, even the flower-decorated garbage can which she doesn’t mind emptying herself. She loves them all; she reminds you of a bride in her new home.

She waves a scoffing hand at such a suggestion. “That’s an illusion,” she says. “Actually the apartment will help to keep me from becoming a bride for a while. It gives me a chance to express my domestic instincts without going domestic. At twenty-three a girl ought to be thinking of marriage. I’m thinking about it, all right. I’m thinking about avoiding it until I have had a chance to realize my investment—the years and the work I have put into becoming an actress.

“People simply don’t take the ambitions of girls seriously unless those ambitions are matrimonial. I can remember my friends laughing at me and my hopes to get on the stage. ‘You’ll forget all about that when you grow up,’ they said. ‘You’ll meet someone and suddenly the dream of acting will fly out of the window as love flies in.’

“Well, that’s no way to treat a dream! Love can fly into my life and love can fly right out again—until I’m ready for it!”

The most sensational brunette to hit Hollywood since Ava Gardner came west from Carolina, Elaine is getting some pained reactions around Hollywood. According to her escorts, she is not kidding.

Among the men who have taken out Elaine Stewart it is pretty well agreed that her dark beauty has an inscrutable “Mona Lisa” quality to it; the better she likes you the less chance you may have of ever dating her again. Any time a friendship gives signs of growing into a romance she makes sure it doesn’t. She has admitted it. “I get to thinking I don’t want it to go too far and from that point on I shy away, I guess.”

As one man reported after he had taken her to a few parties and considered himself a suitor for her hand: “Suddenly I got closed out.” Yet this man is better off than some notable eligibles who can’t even get a date with her.

More than one fellow has been driven to attempt lyrical appreciation of Elaine’s beauty. A rich Hollywood business man felt sure he would win her favor by sending a lovely, gold-backed mirror together with a quatrain about “. . . beauty should see herself in beauty.” Elaine returned the mirror, automatically rejecting the poem. When he telephoned her for a reason she gave him an old fashioned answer: “I don’t know you well enough to accept presents from you.”

Elaine’s stand against romantic hanky-panky at a time when she is getting her career under way was apparent from the moment she arrived in Hollywood. It just took a little time for the word to get around. The first male star she met (and a boy she still likes even if it isn’t going to go any further than that) was Scott Brady. The circumstances of their meeting were not original. Elaine had been brought to a party by her first agent and was standing alone for a moment when Scott introduced himself to her. There ensued an exchange of dialogue so dull that they both cringe when recalling it. Here’s the way it went, word for word.

“Tm Scott Brady. What’s your name? I can’t believe I don’t know you.”

“Elaine Stewart.”

“Where’ve you been keeping yourself?” (He stopped the question there—he didn’t say “. . . all my life.”)

“Around.”

“What’s your telephone number?”

“It wouldn’t interest you.”

Scott looked at her as if she were crazy and assured her, “I’ll get it!”

Elaine never gave Scott her number and he did get it—through studio connections. He phoned her at least a dozen times before she consented to have lunch with him one day. But from that day to this, when Elaine has control of the conversation, they talk only about the business of acting and the conducting of one’s professional life in Hollywood.

When Elaine faced the problem of changing studios (from Hal Wallis to MGM) which eventually became a problem of changing agents, too, it was Scott who came to her rescue and introduced her to her present agent, Johnny Darrow. Darrow, it might be mentioned, is a presentable and successful man, still in his forties, who finds it no hardship to escort his beautiful client to Hollywood affairs. Elaine makes no bones about the fact that she spends a lot of her weekends down at Johnny’s Malibu home. The house is almost always filled with many of his other clients, including Jane Powell and Gene Nelson.

The fellow most people talk about as Elaine’s steady escort is Johnny Grant, popular Hollywood disc jockey and a leader in war entertainment work. Johnny’s comment is, “I wish it were true.” They are good friends, but the friendship is without a romantic future.

“Johnny knows it,” says Elaine, “and I know it. But no one else seems to be aware of it.”

Some of Elaine’s friends criticize her for being too systematic about herself. “Maybe you can plan a career but you can’t plan love,” they say. “Love has to happen. Elaine is trying to live a timetable for success.”

To some extent Elaine agrees with her friends. She believes that nineteen is the ideal age for a girl to marry, and that after that her chances for happiness decrease directly as the years increase. “I’m sure that living alone tends to make a girl more and more complete in herself. In that sense, she can become selfish and less qualified for the partnership attitude necessary to a successful marriage.”

It may be wiser for Elaine to be a twenty-six-year-old bride than to have been a nineteen-year-old one. She has always felt that the ideal husband for her would be a man ten or fifteen years older than she. The reason for this feeling, she thinks, stems from her childhood. She was the eldest daughter in a family beset by debts. In such a situation, children tend to grow up fast, mentally and emotionally. Elaine knew the value of a dollar before she was six years old. If you had it you were Safe; if you didn’t have it you got bad headaches as her policeman father did.

As a child and as a young girl, the only frivolity about Elaine was her desire to become an actress. Because this seemed most unlikely, she played safe and prepared for another career—as a doctor. She graduated from Montclair High School with a B plus average and a scholarship to Green Mountain College for her premedical studies. Had she not become a model in New York, and then an actress in Hollywood, Elaine might be almost ready to hang up her shingle as a doctor—certainly the most beautiful physician in ff the world.

This tendency to think and plan carefully has not changed with her success. It is not something she can control. On her last trip east she went to the Saturday night party of a college group including some of her old friends from Montclair. She enjoyed seeing them again, she loved the dancing and the songs they sang. Yet in their interests, they were from a different world. Most of these kids had not yet felt the weight of responsibility which Elaine has been carrying for years.

A girl whose duties and plans have necessarily been heavy for her age is not going to be lightheaded about romance. Her head isn’t likely to whirl because somebody is holding her hand. Since she knows this, Elaine realizes that married happiness for her is possible only if her husband is mature. “I want him to be a man with widespread interests. I don’t want to be the only thing on his mind,” she says. “From what I have seen of love it dies more quickly from strangulation than from any other cause. I want both of us to drink the same wine, but not from the same glass, as the poet writes. I don’t want each of us to live narrowly just for the other, but to live together in a big, wide world.”

When Elaine was still in high school in Montclair, New Jersey, she had a long talk about her future with her mother, Mrs. Hedwig Steinberg. Her mother delivered a pronouncement Elaine says she will never forget.

“I don’t think it is good for a girl to know too many boys,” said Mrs. Steinberg, “because she tends to think that only boys matter and that her happiness will depend strictly on whether she will choose the right one. It should work the other way. First the girl should choose the kind of life she wants to live, and with this to guide her it is easier to decide what kind of man would make the best partner. She already has an interest in life so she doesn’t expect so much from her husband. In the second place, her interest makes her a person in her own right as well as a wife, and that adds to her ‘stature in her husband’s eyes.”

Few men realize when they meet Elaine and take in her warm, dark beauty that her attitude has such a solid, rational foundation. But they soon find out, as do all her friends and professional associates. Elaine considers all of her steps carefully, whether it’s a question of getting an Italian haircut (which she didn’t) or one of buying a silly-looking but cuddly doll (which she did).

After her fine work as the star of Take The High Ground and the news that her studio had cast her in two of its biggest new pictures, Brigadoon and Athena, many of her friends advised her to change her personality. They thought that she was too approachable and would benefit by taking on a degree of reserve. They suggested a manner somewhere between Olivia De Havilland’s aloof sweetness and Greer Garson’s regality. Elaine didn’t laugh it off. She thought it over and she talked it over. And she decided to remain as she was. She felt she would fool herself more than anyone else if she carried her play acting into real life.

Her salary, heading toward the thousand-a-week mark, has not dazzled her because she knows how to subtract. Take away all the deductions and professional expenses and she has to live quite modestly if she is going to save anything—and Elaine does save regularly. She spends only for essentials. That apartment of hers, in which she lives with a roommate, Suzanne Scheirer, is nice but it’s just like hundreds of apartments in Beverly Hills. Any two girls with fairly good jobs could afford to live on the same level. Her ear is not a Cadillac nor a Mercedes-Benz nor a Jaguar—it’s a ’47 Ford. The dress you’ll see her wearing is not likely to be the product of a famous couturier, but the handiwork of a girl who can sew and whose name is Elaine Stewart. It was because of their mutual interest in sewing that she and Suzanne first met.

All of this makes Elaine sound like a very sensible girl, the kind of girl who would make a fine, thrifty, intelligent—and beautiful—wife. And that is perfectly true. But the man who wants her had better not show up just yet. The lady is too busy.

THE END

—BY JACK WADE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1954