When Does A Husband Think Divorce Is Justified?

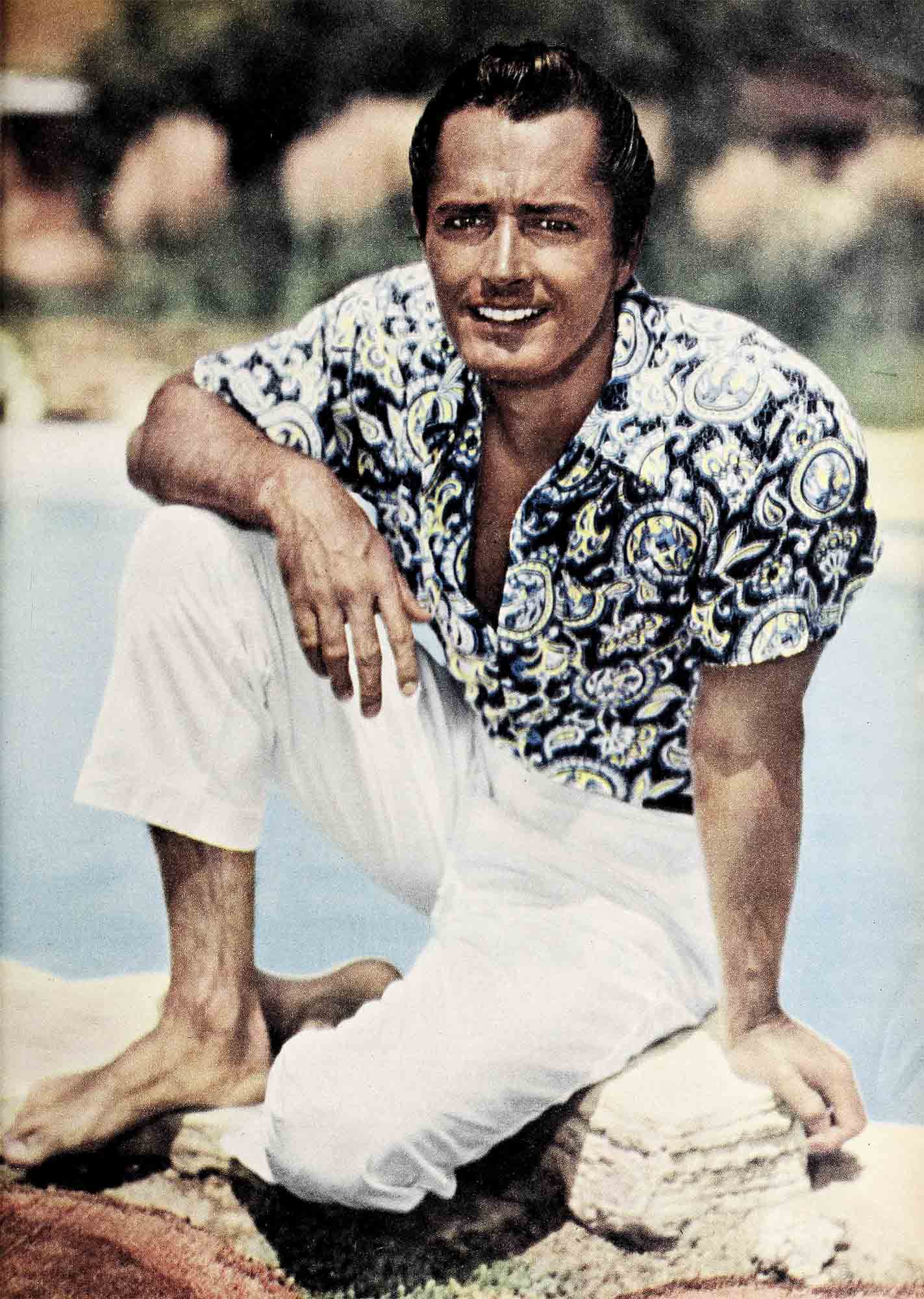

“If I’d had any maturity,” says John Derek today, “I’d never have been married in the first place.”

Now that it is all over, John speaks with startling frankness about his seven-year marriage to Pati Behrs. “In my lifetime,” he says seriously, “I have seen few successful marriages. Oh, people put up a front of compatibility and understanding for the world at large to view, but inwardly—at least in most of the marriages I’m familiar with—the bitter, venomous little feuds go on behind shuttered windows, secure from prying eyes. I think a great many married couples endure rather than love each other. Take my own parents! My earliest memories of them are scarred with hate-filled quarrels. They were divorced when I was five. Dad never had a good word to say for Mother, and vice versa. So I started out in life with a pretty jaundiced view of the institution of matrimony.”

AUDIO BOOK

John’s and Pati’s romance never was a hearts-and-flowers affair. “I was twenty-one and Pati was twenty-three—I think,” says John, “and soon after we met at 20th, where Pati was under contract, we took off for Las Vegas and were united in a three-minute ceremony by a Justice of the Peace. The guy mumbled, and I didn’t hear a word he said. But it wasn’t long after that, that I began: to be vaguely conscious of a slight chafing in the tie that is supposed to bind.

“Love? How should we know?” John shrugs his shoulders. “Although we went together for nearly a year, Pati and I really didn’t know each other. I was a young punk who’d had too much luck in my first picture, ‘Knock on Any Door.’ Suddenly, having done very little to deserve it, I was a star.

“And Pati? Well, women are different. They’re born wise, knowing precisely what they want, which is a home, a husband, and security. They can honestly love a man; but emotion, passion, are nearly always tempered with judgment.

“I don’t mean to imply that I was any great bargain. But I was young, healthy, and seemed to have a good enough future. Oh, I think Pati was much more honest about the whole thing than I was. I think she loved me. But I—carried away by an emotion I didn’t understand, wanting what I thought I wanted that minute, not to- morrow—I never stopped to ask myself, ‘Am I truly in love?’

“Looking back on it now,” John reflects, “I see that ours was a marriage doomed to failure from the moment that Justice of the Peace said, ‘I now pronounce you man and wife.’ But Pati, born in Turkey and reared in France, had a much more realistic, continental view of marriage. She was prepared to work at it while I, governed almost completely by impulse, didn’t actually know what I wanted. Pati was more mature than I—certainly in an intellectual sense—and she was much better educated. She also possessed a quicker mind. She proved this later, when friction started—she won all the arguments.”

It’s no secret that, during their seven years of marriage, John and Pati were engaged in battles which, by comparison, would make some championship boxing bouts seem like friendly scuffles. Now the bell of the final round has rung, and the contestants have retired from the marital ring spiritually, if not physically, bruised. Both of them admit defeat. Neither is happy over the outcome, yet they both feel that, for them, divorce was the sorry but only solution, and they have reached an understanding that was completely lacking in their marriage.

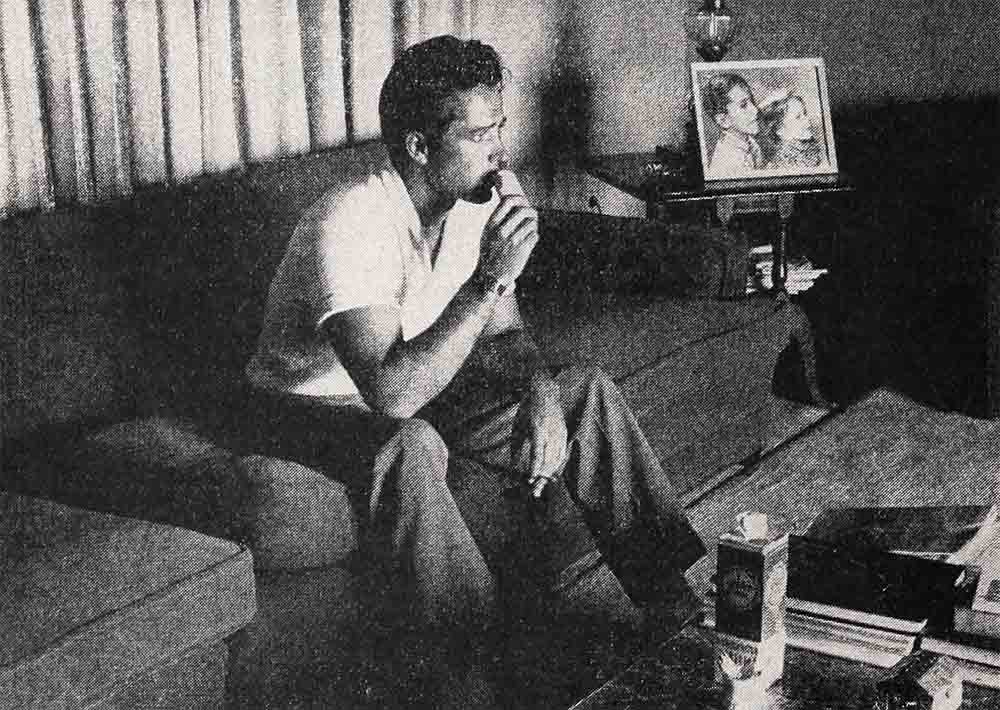

Seated in his bachelor apartment which has been home for him since last fall, John leaned forward in his chair, picked up a magazine on horses and absently thumbed through it. “Beautiful animal,” he said, holding up a picture of a stallion, poised as if ready for flight. “Horses are so much more understandable than human beings.”

Tossing the magazine back on a table, John clapsed his hands nervously between his knees. “I’d like to clear up one thing right from the start,” he went on. “A lot of rot has been printed about ‘the other woman’ in this case. Ursula Andress, the girl everyone insists on dragging into the picture, had not one thing to do with the smash-up of my marriage. I didn’t even know her at the time Pati and I first talked about divorce. I met Ursula accidentally, long after things were over between Pati and me. Since then we have become friends, yes. Ursula is a good companion. She enjoys riding, pistol-shooting and archery. In fact, she likes everything I go for. She’s a man’s girl—competes with me in outdoor things, but never to the point of personal rivalry.

“Do I intend to marry Ursula? Certainly not for a while,” John said emphatically. “I don’t want to marry anyone. Now that I’m free, I intend to remain so.”

John Derek’s views on life and marriage are, to say the least, interesting and unusual. He believes that life, for the average man, is a hard, trouble-ridden journey, and his one consolation is to enjoy himself when the opportunity presents itself. John has consistently pursued this philosophy. An alert young man with a good mind, his pleasures have sprung almost entirely from physical action. For him, swimming, water-skiing, pistol-shooting, archery and, best of all, the feel of a good horse between his legs on a tearing gallop, is about the peak of human enjoyment. John’s notion of the most ideal existence would be to live on a big ranch, well-stocked with the finest horses, enough cattle and crops to make it self-supporting, and two or three good hunting dogs to accompany him when the quail and grouse season opens. And no women within shouting distance! Not that John bars them from his future life. But he wants to be with them only when he feels the need for human companionship.

Today, John maintains, marriage is surrounded by legal restraints and wives are so conscious of their “rights” that the breadwinner is in constant danger of being served with a subpoena if he so much as glances at some alluring miss who chances to cross his path. If he happens to be in a higher income bracket, a wife can nick him for his bankroll and reduce him to near-poverty through court action which gives her a 50-50 cut on everything he makes. All this, says John, tends to create suspicion and distrust in the marital arrangement. The time will come, he firmly believes, when men and women, through mutual agreement, will grant each other greater freedom and thus emerge as more complete individualists and, therefore, more admirable human beings.

Another element which John found completely absent in his own marriage, was Pati’s lack of enthusiasm. As an example, he cites the building of a swimming pool at his big hill-top house. The pool, he says, was a dilly—over 60 feet long and wide enough for an aquatic meet. When it was completed he asked Pati to come out and look it over while he stood by, palpitating with eagerness. She glanced at the layout, he said, then murmured, “Yes, it’s quite beautiful,” and went back into the house. “A wife,” John says, “should show enthusiasm for her husband’s projects, even if and when she may consider them somewhat stupid. It builds up his self-confidence.”

Although he is critical of Pati’s shortcomings, John is not blind to his own. He freely admits that his gravest faults spring from his inability to consider the effects of his. impulsive actions on the family economy. “When I want something,” he said, “I want it at once, not next week or next month. By then, if I get it, the sheen has worn off. I’ve exhausted my capacity to enjoy the thing, whatever it may be. Take the boat I bought. I went to the sportsman’s show, saw this little craft and wanted it. I didn’t have any money—I’m always broke, you know—but I found I could buy it on time. The boat was a honey, with a big outboard motor that would push her through the water at about 32 knots an hour. Well, I bought it, never thinking of the other bills hanging over my head, and after I got it in the water, I found that the speed she had, with only one motor, wasn’t fast enough to race with. So I bought another motor, which cost $740, and now she’ll tear along literally standing on her tail. That’s what I wanted. Maybe I couldn’t afford it, but I did get a tremendous wallop out of that little craft, and later I’m going to race her.

“But you see,” he went on, “business-wise that wasn’t a good bet. It was this sort of thing that made living with me pretty difficult for Pati. She would economize, go without pretty clothes and nearly all the little extravagances that make women interesting and attractive, in order to keep our home shop open. I never asked her to do these things; she simply wanted our house to be well-managed, to run smoothly. She was wifely, an excellent mother to our two children, a conservative, while I was an extremist, an asy spender of money I had yet to earn, a guy who just wanted to be happy in his own way. The truth is, I suppose, that I’m just not suited for marriage. And Pati and I had not one thing in common. She did her best, I’m certain of that, to make our marriage work, and maybe I didn’t try hard enough. But the odd thing is that now, when it’s all over, we’re better friends, more understanding, than we have been. At first Pati was very bitter toward Ursula, but now that she realizes that Ursula had nothing to do with our break-up, she no longer blames her.”

However much John’s lack of understanding has contributed to the ruin of his private life, he has not let this fault influence his career as an actor. James Cagney, who worked with John in “Run for Cover,” remembers him as an extraordinarily gifted performer who managed to extract the utmost out of any scene he played. Cecil B. DeMille, who picked John to play the part of Joshua in his gigantic “The Ten Commandments,” did so because he knew John had the capacity of creating within himself the emotions called for in the script.

Such comments seem even more remarkable in light of the fact that, basically, John does not like acting. In the beginning of his career, he distrusted the whole picture business intensely. “Mouthing words written by others, striking attitudes I thought were phony, not related to natural human behavior, disgusted me,” says John. “But after a while I understood that I had the ability to make imagined anger, distress or suffering become real to myself. This, too, is a kind of phoniness—and I still don’t like it. However, pictures offer me the means of getting what I ultimately want—happiness, the all-important privilege a of being myself and someday owning a ranch where a man can be as free as he can be.”

John has never had any secret longing to go on the legitimate stage. “No,” he says. “All I want now is to be a better actor with each picture I make. That way, my income will rise and I will be so much nearer my goal.”

This goal, however, may be the will-o’-the-wisp that could fade away over many horizons yet unseen. A large percentage of everything John makes will be allotted to Pati and the children, Russell, six, and Sean, his three-year-old daughter. John believes this settlement to be just.

The one aspect of his broken marriage that still disturbs John is the effect it might have on the children.

However, he believes that, in the long run, both Russ and Sean will grow up more normally than would be possible under the atmosphere of strain and dissension which existed while he was hopelessly attempting to be a normal family man. “Children are perceptive little creatures,” John says, “and they sense friction even when parents do their utmost to hide it. You can’t fool kids, and ours were beginning to sense the strain. Now when I go to see them it’s the occasion for a celebration. Russ and I get in my car, go for a ride and have dinner out.”

It is when John talks of little Sean, however, that he reveals the price he is paying for his new-won freedom. When Sean comes into the conversation, his hands move as if trying to grasp a thought out of air. She is, he says, as capricious as a breeze, changeable as a spring day and possessed of an unalterable determination to get what she wants, just like her father. Though she is only half Russ’ age, she wins all her fights with him because she goes into them with single purpose—to come out on top. “She’ll even bite if she has to,” John smiles. “She’s a little terror.”

If Sean is capricious and fickle, she didn’t get this characteristic from the neighbors. Emotionally, John is as unstable as water. Having exhausted one love, he now finds himself on the verge of becoming entangled in another. And while he states, without reservations, that marriage does not enter into his plans for the future, he seems incapable of pursuing a definite unwavering course. Although he earnestly declares that all he wants from life is happiness, John isn’t certain in his own mind exactly what happiness is. Currently he defines it as living to the fullest, doing what comes naturally, envisioning the goal of a free-flown existence on a ranch of his own. “I just want to live my own life without hurting anybody,” he says, not realizing, apparently, that in this complex world such an ideal has yet to be achieved, in or out of marriage.

Thus at thirty, with “everything”—wife, home, successful career, lovely children—John Derek felt that, in spite of all the heartache that might ensue for everyone, there was no other recourse for him and Pati but the final surgery of divorce. Obviously it was not a step he took lightly, but on the other hand, one may question John’s definition of marriage, and his feelings about a wife’s duty to her husband, and ask whether any wife—no matter how loving—can live for her husband alone?

Certainly it’s true that no one can live for himself alone and find happiness. But perhaps that’s a lesson John Derek is only now learning, and one on which his future happiness—eventually in another marriage—will be based.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1956

AUDIO BOOK