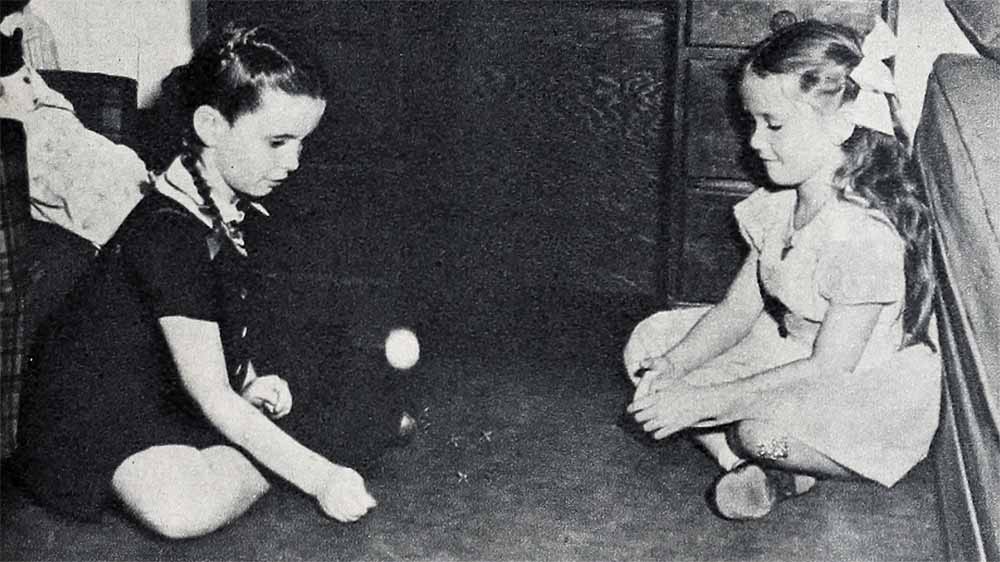

Junior Pin-Up

The young mother’s hair was a black smudge separating her white face from the pillow. Across the room a baby cried.

“She’s straight and strong, you’re sure?” the mother asked the nurse once more. “Poor little thing . . . with her father dead and a mother like me . . . My life’s over. . .

“When you aren’t so tired,” the nurse promised, “you’ll feel otherwise.”

Tired . . . she tried to remember when she hadn’t been tired, how it had been when she had had Larry and, as Gladys Flores, she had utterly forgotten her audience in the joy she knew in the music and her dance. The last six months without Larry had been long. Widowhood had not grown easier with time. Often it seemed as if the weight of her heart was greater than that of the baby lying beneath it. She had kept on dancing, not because there was any joy left in it, but because she needed the dollars it earned. She had held her last class the day before the baby was born. It had been useless for her sister Marissa, also a dancer, to plead with her to give up her classes. “We’ll need every last penny I can lay by,” Gladys always answered.

The baby was christened Angela Maxine—Angela Maxine O’Brien. She was a pretty baby, largely because of her eyes. In those eyes lay all the innocence of a life yet to be lived, coupled with the wisdom of the ages. She was a good baby too. So seldom did she cry that by the time she was eight months old Gladys O’Brien had the courage to launch upon a bold plan. She moved her little family into the smallest double room available at the Waldorf-Astoria. It was cramped quarters for her and the baby and Marissa. Getting Angela Maxine in unseen was an accomplishment achieved by the benefit of a steamer rug she carried casually over her shoulder and over Angela, lying against her arm.

“You’re going to dance right here in the Wedgwood Room,” Gladys told Marissa, so much younger that she also was her child in a way. “Be well paid for it too. Living here we’ll convince them we can afford to name our own price.”

Slowly, as her strength had flowed back, Gladys had started dreaming for Marissa again.

“You have such courage,” Marissa told her, a little frightened sometimes by the scope of the dreams.

Gladys laughed. “Courage is a politer word than Larry used. Remember, he always called it darn foolishness.” But her tone made the charge an endearment.

The women were bending over the twin bed in which Angela Maxine was propped up with pillows. A chambermaid had brought extra pillows. And instead of objecting to having a baby on her floor, the floor clerk was forever telling Gladys and Marissa she’d be glad to take charge any time they wanted to go out.

Gladys never took advantage of this offer until the night Marissa opened triumphantly in the Wedgwood Room. Upstairs, at the same time, Angela Maxine knew triumph, too, as both chambermaid and floor clerk, supposed to frown on babies in their domain, marched up and down the counterpane the plush animals they had brought her and kept her awake long past her bedtime.

When Marissa finally concluded her engagement at the Waldorf the O’Briens returned to California. In Hollywood it was hoped Marissa would find more glory. It wasn’t only for Marissa they wanted success now. Angela Maxine was walking, talking. Sometimes they had to skimp to pay for regular examinations by a good pediatrician and the diet he ordered. They loved her so they wanted the best for her. How could they guess she soon would be taking handsome care of herself?

First Paul Hesse, attracted by the glamour Angela Maxine brought to pigtails, photographed her for magazine covers. Then she played in a government short with James Cagney and did a bit in “Babes On Broadway” with Mickey Rooney. When Metro was searching for a little girl to play in “Journey For Margaret” an office worker remembered the piquancy of a youngster she had seen in “Babes On Broadway.” Whereupon the executives re-ran the film and promptly signed Angela Maxine for the plum role.

It was then that Angela Maxine became officially Margaret O’Brien—and a new star—and the pin-up girl of thousands of homesick GIs who write her, “You remind me of my own little girl”—and the inspiration for a certain pursuit plane named “Lost Angel”—and the darling of millions, including those two perfectionists, Charles Laughton and Lionel Barrymore.

“She’s the only actress besides my sister Ethel who has brought tears to my eyes in thirty years,” Lionel Barrymore tells you. Last Christmas he gave Margaret a little pin of amethysts and seed pearls which once belonged to his grandmother.

“These are crown jewels, in a way,” Margaret explains, “because they came from the theater’s ‘Royal Family.’ And they’re all the royalty we have in America.”

She talks in a gentle voice with a fairly high register. And when she’s very interested in what you are saying she will take your hand in a gesture so trusting you remember it for a long, long time.

Late this winter, when Margaret and her mother and aunt were in New York, we all had breakfast at the Waldorf. Their drawing-room was filled with spring flowers. And there was a bird singing. Margaret had brought it from California and had worried over the size of the tiny cage in which she had carried him until Elsa Maxwell had given her a larger cage whose erstwhile occupant, a parrot that insisted upon cursing in Japanese, had departed.

In one of the bedrooms was Guadaloupe, Margaret’s Mexican nurse. She had been a chambermaid in the hotel in Mexico City during the O’Briens’ visit there and had looked after Margaret whenever Gladys and Marissa stepped out. Margaret had been entranced by her because, among other things, she bore the same name as the shrine where they made their devotions.

Margaret, wearing a housecoat and pink bunny bedroom slippers, eyed the plate of glazed Danish pastry and waited for her mother to finish what she was saying.

Suddenly, taking advantage of her mother’s pause for breath, she announced, “I have a beautiful new nightgown underneath. Could I show it, Mommie, please?”

Her gown was pink satin, shirred fully at the yoke and edged with fine lace. “It’s just like a movie star’s, isn’t it?” she asked, wrinkling her nose with delight. “Just like something Miss Garson would wear.”

Margaret had spied the gown, a maternity gown of the new short length, when they had been shopping. The length had convinced her that it was meant for a little girl. And she had pleaded for it.

Breakfast over, Margaret placed an open box of bird seed on the table. “I’ll show you,” she offered, “how Francesca, my bird, will sit on my finger and nibble at the seeds. Guadaloupe taught me how to take her up gently. At first I did it when it was dark so she wouldn’t see my hand coming toward her and be frightened.

“Guadaloupe’s teaching me Spanish too. And I’m teaching her English. Auntie taught me to print my name—Margaret— so I can sign pictures and drawings and not be too far behind when I start school.”

As she whispered to Francesca before opening the cage, her aunt was telling of a party she had been on the night before and the attractive man who had been her escort.

Margaret suddenly paused. “I do hope you won’t marry him, even though he is so nice,” she said with gentle firmness. “I want you to marry—you know who!”

Marissa laughed. “Margaret wants Fred Wilcox for an uncle-in-law so we’ll have Lassie in the family. Mr. Wilcox directs the Lassie pictures, you know.”

Francesca stepped daintily onto Margaret’s finger, then took to the air.

“Margaret,” Mrs. O’Brien said, “while Francesca’s flying would you recite ‘The Nativity?’ ”

She was like any mother asking her child to recite. And Margaret, facing us to begin, was like any obedient child. There, however, all similarity ended. As she told the story of the Baby in the manger she wove a spell. We could see the shepherds watching the flocks and the shine of the gifts the wise men carried so carefully. We could hear the wings of the Heavenly Host . . . only they suddenly turned out to be the wings of Francesca trapped in a basket of spring flowers. Margaret rushed over to free her.

“There, Francesca,” she whispered. once again she was a little eight-year-old all concerned about her pet. Her magic gift fell from her like an invisible cloak.

Marissa said, “Francesca goes into her cage much better than you go into your bed, Margaret.”

“When we tell Margaret it’s bedtime,” Gladys smiled, “she suddenly remembers she has to dress her twin dolls, put water in Francesca’s dish, finish a drawing.”

Margaret grinned. “I dawdle.”

At this point some men arrived to discuss a broadcast for Margaret. Bored with the business conversation she retired to a big secretary and began to draw a nun. Nuns and glamour girls—especially with red hair like Miss Garson—are her specialties. Her drawings are unlike those of most children her age. They show a subtlety of facial expression with a curious consciousness of “good” and “bad.”

“I’d draw a glamour girl for you,” Margaret offered, “but I don’t have the right color crayons.” She held up three, enumerating the colors—“black, yellow, brown.”

As we were leaving, Gladys O’Brien said, “We know so little of what lies ahead for us. A few months ago Guadaloupe would have thought anyone who told her she was going to leave her sunny native city was crazy. Now she has seen California, travelled across the entire United States, and she stands watching a New York snowstorm. If only we could always remember how quickly life changes we would never feel, as I did when Margaret was born, that life is over. How little I knew of the wonderful things that were ahead.”

Again Margaret’s soft little hand slipped into ours as she said good-by and presented us with her picture of a nun. “I’ll do a glamour girl next time when I have the right crayons,” she promised.

Outside the snow was falling thick and fast. Through the white veil loomed the gold and scarlet sign of a five-and-ten-cent store. Here was a clear indication of what should be done. Maybe it seems ridiculous to send a ten-cent box of crayons to a famous movie star. But it isn’t, somehow, when she’s Angela Maxine O’Brien, so much better known as Margaret.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1945

Madeleine Harvey

8 Ağustos 2023Nice article! Also visit my blog about Clomid success stories