Look At Me, Love Me, Anyone!—Susan Hayward

The little girl held her arms tightly around her father’s neck as he lifted her from the bench in the crowded hospital waiting room. Her heart-shaped face was white against its frame of bright-red hair as he carried her into the clinic next door.

“Over there,” the young doctor said, nodding toward the white-sheeted examination table in one corner. He spoke curtly, reading from the registration card the nurse, her white uniform wilted from the heat, had brought in. “Edythe Marrener, six. Car accident. Dislocated hip. Internal injuries.”

“That was six months ago,” Walter Marrener explained. “We’ve been caring for her at her home. You see, she ran into the street . . .”

“I had to catch my parachute before it got run over.” The girl’s voice was unexpectedly clear.

“Was it a real one?”

“No,” the girl told him, “just a paper one.” The doctor’s face relaxed into a smile as he put down the registration card and turned to face her. “All right, now, young lady,” he said, “let’s see you stand up—” Automatically, Edythe’s father hoisted her to her feet and held her for a moment.

“—Alone,” the doctor added. Cautiously, her father let go, and Edythe’s tiny hands gripped the wall tensely, her legs trembling under her. But she was standing, looking gravely up at the doctor. “Now walk,” he commanded gently.

Mr. Marrener stepped back two paces and bent toward her, his arms outstretched. The moment she let go of the wall, her legs crumpled beneath her as if they had no bones. Mr. Marrener took the sobbing child in his arms. “There, there, sweetheart,” he crooned, his own eyes filling with tears as he rocked her.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Marrener.” The young doctor’s voice was soft, but nothing could ease his verdict: “I’m afraid you’re going to have to face it; the X-rays show your daughter is going to be permanently crippled.”

That afternoon, in the same third-floor-front room where she’d been born, Edythe lay on her bed, pretending to sleep as her family murmured in the kitchen. “Edie’s tired from the trip to the hospital,” Ellen Marrener told her older children, Florence and Walt. “You can play with her later.”

On the street below, Edythe could recognize each of the shouting voices. “In clear! In clear!” they chorused. On this July afternoon they were playing, but in September they’d be starting school at PS. 181—the grocer’s curly-headed son, the cop’s little towhead, both Edythe’s “boyfriends,” who paid her regular visits—all the kids.

“Edie! You mustn’t!” Her sister’s cry brought Walter Marrener hurrying, too late to keep Edythe from wriggling over the edge of the bed and touching her feet to the floor.

Propped against the bed, she was trying to stand up straight when her father reached out for her. “No, no! Don’t pick me up,” she cried. “Help me, Daddy—help me walk.” With his hands firm under her arms, she turned from the bed. Her face crinkling with effort, she moved one foot forward, then the other. And then her knees buckled. But this time she didn’t weep. All she said was “Tired . . .”

Swooping her up to his chest, Walter Marrener said, “Sleep now. We’ll try again tomorrow.”

A few days later, he appeared in her doorway with his hands behind his back. “Present for you, Edythe,” he said, a glint in his eye. “A brand-new kind!”

She had been inching along one end of the bed, holding onto the footboard while she set one foot slowly ahead of the other. Her father swung his hands around and held the present toward her. It was a pair of children’s crutches, but the way her face lit up, you’d have thought it was a pair of angel’s wings. “You hold them like this,” he said, fitting them gently under his arms.

“I know, I know!” she said breathlessly. “Now, let go of me, Daddy!” He stepped back and clasped his wife’s hand as she, too, came into the room. They saw their daughter lean against the footboard to adjust the crutches, shift her full weight onto them and, finally, onto her own two feet. Then, slowly, she began to walk toward her parents, looking down at her feet first in concentration, then in wonder and delight. And she lifted her head with a child’s sweet, crowing laugh of pure happiness.

When all the kids started at P. S. 181, Edythe Marrener was with them. Each day her mother pulled her to school and home again in a little red express-wagon, and she hobbled through the hallways on crutches till the end of Grade 2-A. No one ever heard her whine, but then, few heard her laugh, either. For even after her crutches were discarded and she walked straight and proud, Edythe still felt different, somehow cut off from her classmates. . . .

In the auditorium at Girls Commercial High School (now known as Prospect Park High), Edythe Marrener sat a little apart from the other members of the dramatic club. They sometimes shifted in their seats, exchanged whispered remarks. But she was utterly intent on the stage, where a slender blond girl was reading from a script.

“Speak out, Mary,” interrupted Dorothy Yawger, sponsor of the club. “You’ll never reach the last row of the balcony that way.”

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Yawger.” Strengthening her voice, the girl went through the last lines of the love scene and came down from the stage.

“Anyone else trying out for Helene?” Mrs. Yawger asked. “You, Edythe?”

“No, Mrs. Yawger. I thought I’d rather try for Agatha. You know—the old woman who comes on in the second act.”

“I see .. .” With a searching look at the beautiful but puzzling Marrener girl, the teacher again consulted her notes. “Well, I think Mary’s our leading lady. Now does anyone else want to read for Agatha? . . . No one? I guess that makes the part yours, Edythe. That’s all for today, girls. Rehearsal next Tuesday at three-fifteen sharp—and I want you all to study your lines hard over the weekend.”

A chatter of young voices broke loose: “. . . They’re real smoothies—said they’d meet us at the drugstore . . . Let’s go to the Glenwood. Joan Crawford—and they’re giving away soup dishes today. My mom . . . Come on over to my house —I’ve got a new Cab Calloway record.” The girls streamed out of the auditorium by twos or threes, but Edythe Marrener walked alone.

“May I speak with you a moment, Edythe?” Smiling at the friendly note in Mrs. Yawger’s voice, the girl paused. “Why didn’t you want to try out for Helene? You’re certainly pretty enough to be the heroine.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Yawger.” Edythe began to laugh. “I guess I had enough of playing princesses at P. S. 181. Miss Rappaport always made me the fairy princess—even when I was a bad fairy who didn’t believe in Christmas.”

“But you know you’ll have to wear a homely sort of makeup as Agatha. And it’s an unpleasant part—the audience won’t like you.”

“It’s a good acting part,” Edythe said quietly. Even then, she knew . . . vaguely . . . “I want something . . . something more than other girls.” She couldn’t express it, but she wanted people to recognize her and love her. Edythe Marrener was seventeen, and she could only hear the silent cry in a seventeen-year-old heart: Look at me, love me, anyone! . . .

After finishing school, she decided to become a model, and she worked hard at it. Her father was bedridden and the family had moved to an even shabbier Brooklyn apartment, but it was all she could do to keep up with the rent.

Every time the phone rang, she would rush to answer it because she hoped it would mean another modeling job—maybe an illustration for an etiquette column, in which she would superbly portray a dinner guest picking up the correct fork.

Then one day, without warning, a voice on the other end of the line said, “Miss Edythe Marrener? Kathrine Brown of Selznick International Pictures calling. One moment, please.”

The name “Selznick” was enough to panic her. Everyone in the country at that time knew the producer was hunting for an actress to play Scarlett O’Hara in “Gone With the Wind.”

“We saw that modeling story in the Saturday Evening Post, Miss Marrener—and I must say we were very favorably impressed. Girl, you’re really photogenic! Have you any acting experience?”

“Several school plays, and—”

Edythe heard her voice falter, and prayed that she sounded all right—that her Flatbush accent wouldn’t ruin things. She remembered her dad’s advice: “Always keep your voice soft, Edie,” he’d told her. “Remember, you’re a little lady. You’re not trying out for my old job at Coney Island!” (In his youth, before he had a family to support, Walter Marrener had been a barker at a sideshow.) Swallowing hard she went on in carefully low-pitched tones, “And I’ve been studying drama for five months.”

“Good! Now, Miss Marrener, I suppose I don’t have to tell you what we have in mind. Every time my office door opens, I hope I’ll see Scarlett O’Hara walk through it. The picture’s started shooting, you know, and what’s ‘Gone With the Wind’ without Scarlett? Can you come in this afternoon?”

Of the rest of the conversation, only the essentials were fixed in Edythe’s mind: three-thirty, 630 Fifth Avenue, thirty-fourth floor. As she fumbled the phone back onto its cradle, her thoughts were racing far beyond the interview.

“Edie, what’s the matter?” Dish-towel in hand, her mother stood in the kitchen doorway. “You look all upset.”

Edythe started to laugh. Then all of a sudden she was sobbing and throwing her arms around her mother. “Oh, Mom, I— No, wait. Come on into Dad’s bedroom. I want to tell you and him both at once.”

Looking gravely into his daughter’s face, Walter Marrener heard her finish, “Then I’ll read a scene for the talent scout, and if he thinks I’m good enough, I’ll be given a screen test. Then Hollywood, and—”

“I hope you don’t get it.” His voice was urgent and his large hands trembled on the bedcovers.

Startled, Edythe and her mother turned toward him. “Why, Dad . . . Oh, I see. You just don’t want me to be disappointed—just in case . . .”

“No. It wouldn’t be good for you.”

At his words Edythe felt a chill But she chose to put a lighter interpretation on the warning. “I know I haven’t much experience,” she told him, “and maybe I shouldn’t rush ahead so fast.” She dropped to her knees beside his bed and put her hand on his shoulder. “But don’t you see, Dad? Right now, I have to believe I’m going to be Scarlett! If . . . if I don’t get the part, why, I’ll be out there anyway, are going to look at me and know me!” . . .

Who’s the gorgeous redhead?” said the salesman from South Bend.

“Some starlet, I guess,” said the salesman from Bangor. “You know—the kind who spends all her time posing for cheesecake and never makes a movie. Hey, here comes Gary Cooper!”

While Paramount proudly introduced its top stars at the company convention in Los Angeles, the anonymous redhead sat far off on one side of the auditorium stage. Sat and seethed. Inside, the girl who used to be Edythe Marrener was boiling up. For her two months at Selznick, she had nothing to show but a flunked screen test, and for almost a year at Warners, nothing but lots of leg-art and a new name that nobody knew. Then for almost two years at Paramount, nothing but a few bits and an insipid role in “Beau Geste,” a fairy princess who did a fast disappearing act.

Production chief William LeBaron had worked his way almost to the end of the Paramount contract list when he finally said, “Now I want you to meet one of our most promising new actresses. Susan Hayward!”

Red hair whipping after her like a defiant flag, Susan crossed the stage and seized the microphone. “Did anybody in the house ever hear of me before?”

Astonished silence was followed by laughter. “No!” shouted the salesman from South Bend.

“No!” shouted the salesman from Bangor, along with the men from the other Paramount exchanges, who knew that theater-owners demanded names.

“You said it!” Susan snapped, hands on hips, frankly Flatbush. “But I’m drawing my salary every week. Is that economics? Do any of you boys out there get paid if you don’t deliver?”

“Nooo!” The shouts built into a lively clapping of hands.

“Anybody in the house like to see me in a picture?”

“Yes!” Applause roared up at her.

Abruptly, Susan turned to Mr. LeBaron. “Well, how about it?” she asked the boss. Then, without waiting for an answer, she threw back her head and sailed off the stage.

After that, she began to start working, to start being noticed.

“There’s Susan Hayward!” The youthful GI’s freckled face lit up in admiration as he nudged the sailor next to him.

“Where?” The sailor turned and gave a soft, appreciative wolf whistle. “Oh, yeah. You see her in ‘Adam Had Four Sons’? Man, what a witch!”

“That was actin’, ya dope! She’s a nice girl. Let’s go over and talk to her.” Through the uniformed crowd in the Hollywood Canteen, they headed toward the poised redhead at the tea table.

For the moment, Susan’s mind wasn’t on her job; she held an empty cup under the spigot of the silver urn, and her fingers rested forgetfully on the handle. She was looking at a tall, blond young man who’d just come out of the kitchen with a heavily loaded tray. Suddenly their eyes met. She caught a bright blue glint of answering interest and quickly returned, in embarrassment, to her tea-pouring. But she was thinking, “Please, look at me. . . .”

“Hello, Miss Hayward.” Startled, she glanced up to find one of the Canteen’s GI guests beaming at her. “Me and my buddy, we’re both fans of yours. You were great in that show at Fort Ord. Remember, you stepped right up and hollered, ‘I’m from Brooklyn. Anybody else here from Brooklyn?’ Well, I am!”

Even while Susan shook hands, her eyes watched the tall blond man who was busy unloading stacks of saucers onto the tea table. He looked back at her, grinned and, before she knew it, was coming toward her.

“Is this club for Brooklynites only? Or can a fella from South Carolina join up?”

Susan laughed, “I’d love introducing you, only’I don’t know your name.”

“It’s Jess Barker, ma’am.” . . . he answered in a soft Southern drawl. And she had no idea that months later she would become Mrs. Jess Barker.

But as her career progressed—she began piling up Academy Award nominations—her marriage, after ten years, faded.

Susan slid the wedding ring back and forth on her finger as she forced her halting voice to go on. “Someone loves me,” she had thought when she first wore the ring.

Now she had to repeat in the divorce-court words she had spoken on an ugly night that she wanted to forget: “ ‘If you don’t love me, why don’t you get a divorce?’ . . . I told him, ‘I don’t under- stand you.’ Then he slapped me—twice—and knocked me down.”

She heard the judge’s words: “Decree granted.” That’s what she’d wanted to hear; it was the only possible solution, painfully arrived at after bickering, quarreling and violence had torn their love to pieces. Yet, when it ended, it seemed to have a frightening finality. Her future looked blank and dark, full of questions that had as yet no answers. . . .

She was looking at a white ceiling. Morning sunlight poured into the room, but it was a strange room, and the narrow bed beneath her was strange. She felt lost and terrified.

Memories of the night before confused her. She hadn’t been able to sleep that night. She hadn’t been able to stop her. mind from thinking. So she’d taken sleeping pills—too many sleeping pills. And they had brought her to this white room.

She lay there, awake. She was alive! For a few hours, she put on a frilly, embroidered nightgown, brushed her hair and added lipstick to her pale mouth. Then she faced the reporters. “I feel wonderful!” she told them.

Four days later, in a bright print dress, she was ready to leave the hospital When an attendant brought a wheelchair into her room, she asked, “What’s that for?”

“Hospital rule, Miss Hayward.”

“That’s nonsense,” she answered. “I can walk alone—now!”

It was true, she could walk alone, but on that night at the Pantages Theater, she knew that she didn’t want to.

“Nominees . . . Susan Hayward, for ‘I’ll Cry Tomorrow.’ ”

Deliberately, Susan made her hands lie quiet in her lap. Her heart was pounding. Surely, this must be the time. She had worked so long, so hard!

“The winner is . . . Anna Magnani, for ‘The Rose Tattoo.’ ”

Tensed for a moment, Susan’s hands lifted, and the palms beat together in applause. She was smiling, and—to her own surprise—no threat of tears disturbed her smile. Glancing toward the nearest exit, she was already planning to leave as quickly as possible when the ceremonies were over, for she had planned a party at her home—win or lose. At that party she was to meet a man who would change her life.

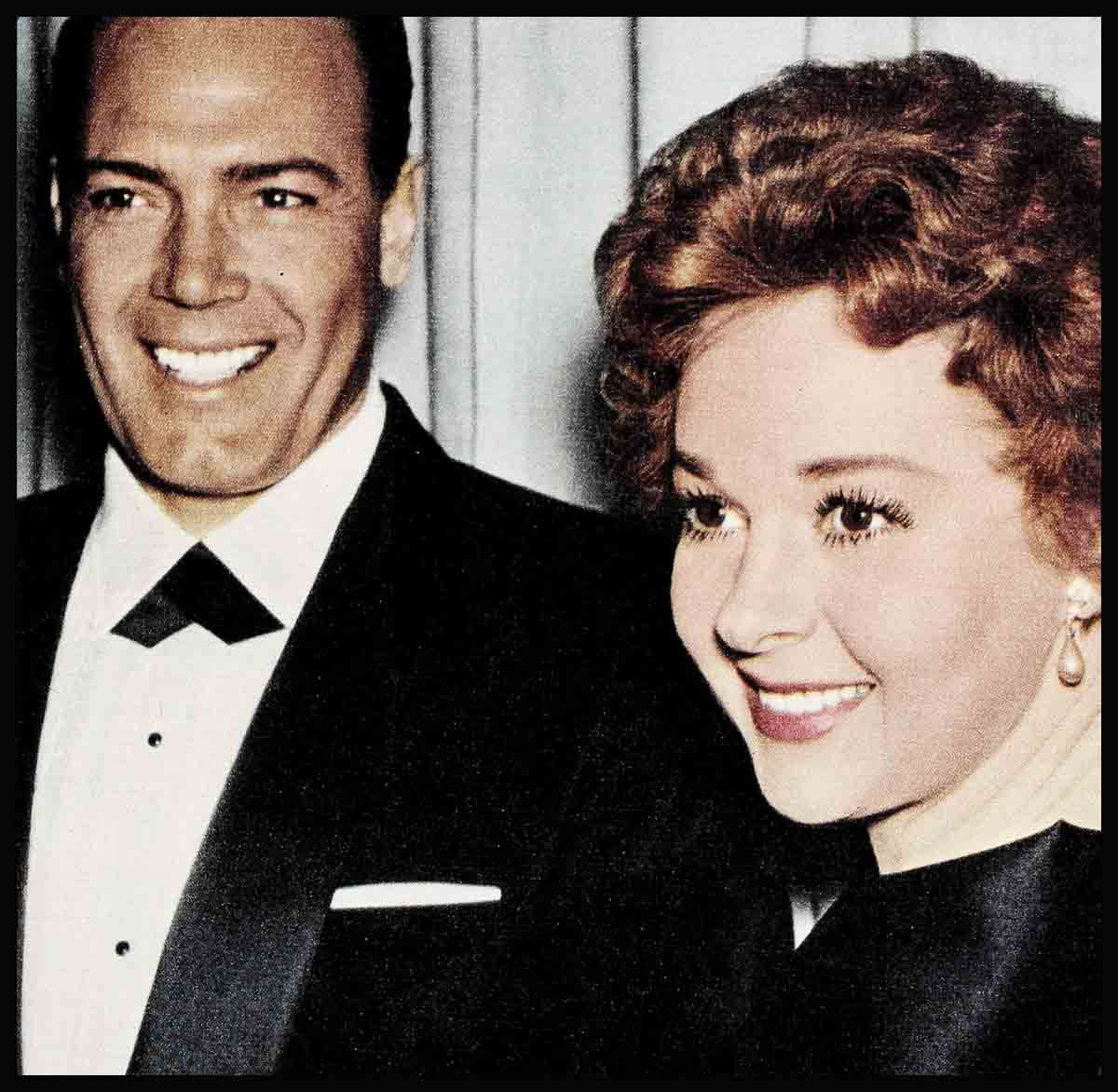

The names on the marriage license were Floyd Eaton Chalkley and Edythe Marrener. It was February 8, 1957. The tall good-looking Georgia lawyer slid onto Edythe-Susan’s finger a wedding band set with diamonds and whispered thoughtfully, “I love you . . . you are my wife.”

She was wearing black satin again, but in a subtler design than the dress she’d worn on an earlier Academy Award night. It was April 6, 1959. Her husband’s big hand was folded reassuringly over hers, but she couldn’t help frowning in suspense as she watched Kim Novak and Jimmy Cagney up there on the dais, watched the white envelope in their hands, and tried to steady her thoughts as they opened it. Then she heard the unbelievable—

“The winner is . . . Susan Hayward, for ‘I Want to Live!’ ”

The applause deafened her next thought, and then, like a long-coiled spring suddenly released, she was out of her seat and walking up the aisle “with the proud, quick, graceful step,” as one friend remarked, “that has been a lifelong mark of Susan’s character”. . . .

When “he” stood on the table in their Beverly Hills Hotel suite, slim and golden and awfully small to have created such a fuss, surrounded by a forest of red roses tagged with congratulatory cards, Susan said softly, “I’ve wanted an Oscar for so long. Winning him means so much to me.”

“I know,” Eaton said, his arm around her. “But we still have a plane to make. We’re going back home tonight.”

With her Oscar cradled in her hands, Susan walked across the room and, looking down at the cherished award, she thought funny, I wanted one of these so desperately when it seemed as though I had nothing else. Now I already have everything I want from life—and now is the time I win! The lid of the suitcase closed over Oscar. “He’ll look wonderful over our fireplace,” Susan said.

“Every home should have one,” Eaton agreed.

—JANET GRAVES

CURRENTLY IN 20TH’S “WOMAN OBSESSED,” SUSAN NEXT FILMS U-I’S “ELEPHANT HILL.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1959

No Comments