She Beat The Barrier Of Beauty

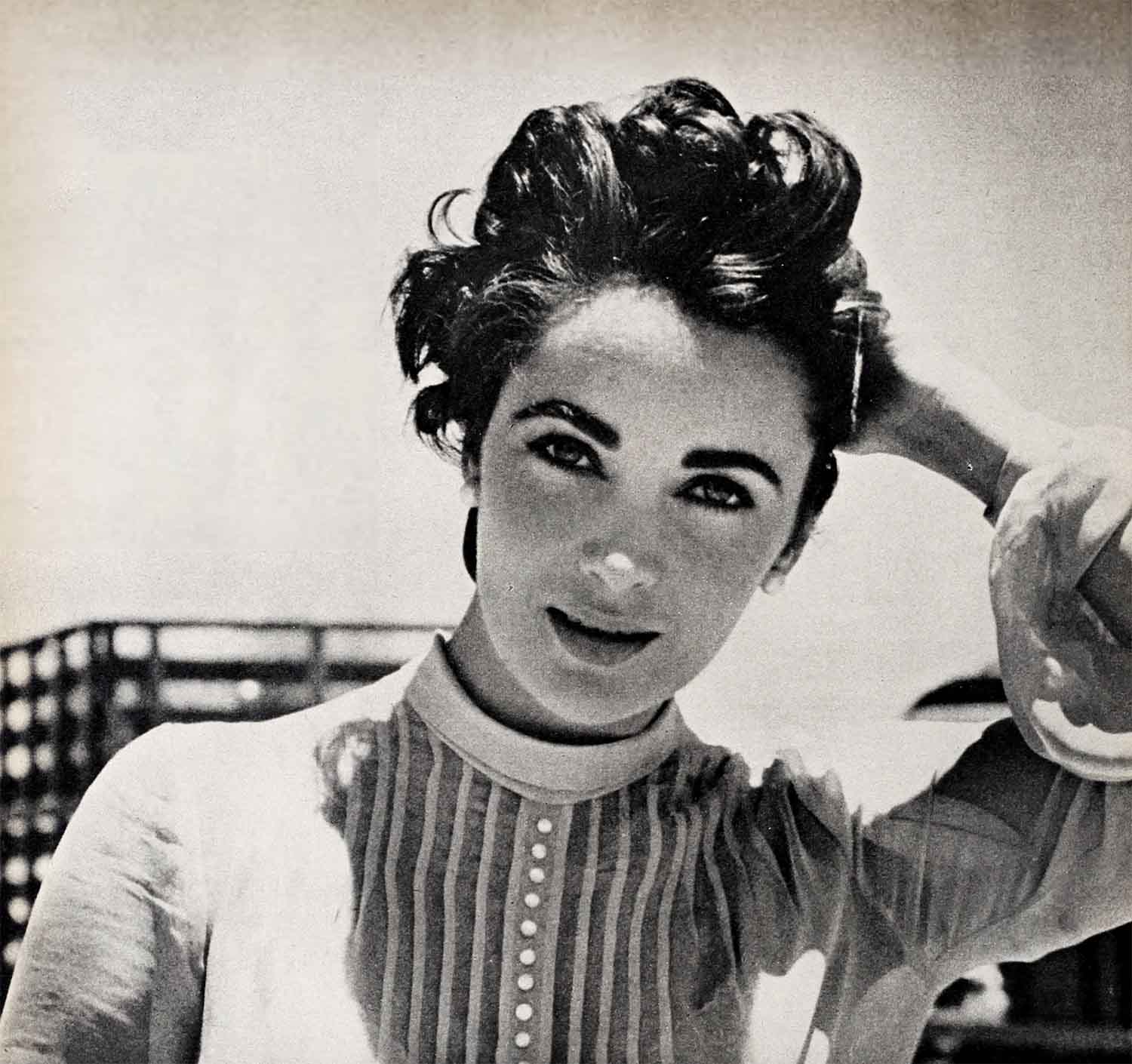

The brother of the Caliph of Morocco was giving a ball, the elegance of which could be matched only by an M-G-M Technicolored spectacle. But, in spite of all this, the eyes of the guests were fixed upon a visitor from America . . . Elizabeth Taylor, who had accompanied her husband to Morocco on a picture location.

The crowd watched as Michael Wilding and the vision of beauty who is his wife moved onto the dance floor. Then other men bore down upon the couple to claim a dance with Mrs. Wilding. “What they say is true,” murmured one dignitary awaiting his turn. “No one could be more exquisite.”

The music played on and the dancers responded and the multitude encircling Mrs. Wilding grew larger. As is the custom in Morocco, partner after partner cut in by taking hold of her arm, Before long, her arm began to ache, but her smile remained gracious. Two steps, change partners . . . three steps, change partners. She was whirled around and around the room. Somewhere in the confusion, she lost a diamond earring. She never found it. The jeweled brooch that she was wearing came unclasped and fell to the floor. The jewels were recovered, but the brooch was crushed.

Hectic as it was, the Moroccan tribute might have been considered a triumph by any girl. It might also have been taken for granted by many. Yet, as the Wildings left the ball later in the evening, Elizabeth smiled at Michael and said, “How nice of them to be so attentive to a stranger.”

To those who know her, the reaction was a typical one. And those who know her best are also aware that the price she has paid for her beauty cannot be measured by material things—a missing earring, a crushed brooch.

Scores of her fans might find it difficult to believe that, for Elizabeth. the price has been higher. To most, she is a star who represents a dream—the one that came true. Countless young girls slip into the world of make*believe as she brings it to the movie screen. In the dim theatre, the glare of reality is left outside and for a time seems far away. A teenager’s painful shyness can be lost, if only briefly; today’s misunderstandings will be easier to return to, after a short respite; disappointments are momentarily forgotten.

But, let Van Johnson describe a telling scene that occurred just five short years ago:

“ ‘The Big Hangover’ was the first picture we did together,” Van recalls. Although Elizabeth was playing a twenty-five-year-old woman, she was really only seventeen years old.

“She was still going to school when we were making the picture,” Van continues, “getting ready for her final high school exams. One day when I passed her dressing room. there she was with a school book in her hand, but gazing at the ceiling with a tragic look.

“ ‘Hey, sugar,’ I said. ‘what’s wrong?’

“ ‘Oh, Van, I’m so depressed,’ she sighed. ‘I just feel as if I’d like to die today.’

“You couldn’t laugh; you remember too well how it was when you were having growing pains yourself. ‘Do me a favor, honey?’ I said. ‘Just get up and take a look in the mirror, will you?’

“I don’t know, even then, if she could see in that mirror what is evident to those of us who know her,” says Van. “Beauty, yes, but so much more than beauty. There was girlhood with every facet on tap, and there was the promise of womanhood with all the instinct, emotion and intellect to assure it.”

Elizabeth, however, to the people in a movie audience, has always been the girl on the screen who has no problems that cannot be solved in ninety or a hundred minutes, depending on the length of the picture. She knows exactly what to say and when to say it. And even if she could find no words, she would need none because her features are perfection. Everything will go well for her. And why not?

Off-screen, she is equally as lovely. And she is successful, famous, wealthy, happy. She is the belle of the ball, to be admired and envied. And people say, “No wonder. Look at that face.”

To so many, beauty represents not only a goal, but a solution as well. “If only I were beautiful,” sighs a teenager. “Then people would see me as I really am.”

But would they? How many would look beyond the eyes—almost deep violet in color, fringed with dark, incredibly long lashes—beyond the perfectly formed mouth, the clear white complexion, beyond the picture to the girl herself? And how many would stare as if at a painting and inquire, “How does it feel to be the most gorgeous creature alive?”

It was a long time before Elizabeth found the words to give the answer to that oft-asked question. When she was small, she would blush and turn away and murmur, “I don’t know.”

“But you are. . .”

“People say that to everybody. . . .”

Recently, the question was asked again, by an inquiring reporter.

“Are you married?” Elizabeth asked the reporter, turning the tables.

“Why, yes,” replied the scribe.

“Tell me about your husband,” suggested Elizabeth.

“He’s a pretty wonderful fellow,” grinned the lady. “I may be prejudiced, but I’d say that he’s about the kindest man in the world—and the most thoughtful. And he’s a pretty terrific father. . .

“Is he handsome?” asked Elizabeth.

“Come to think of it, he is,” said the reporter. “He’s darned handsome, but—”

Elizabeth smiled shyly. “But appearance isn’t the most important quality about a person.”

The writer caught her smile, and the point she was making. “Questions like mine must give you a great deal of trouble,” she said. “Consider it withdrawn! Frankly, I don’t know how you’ve been able to take it for a lifetime!”

“Elizabeth has always been beautiful,” her mother wrote when her daughter was nineteen. “When she was a very tiny little baby, she was, I thought, divinely beautiful. Other people, however, thought her ‘plain,’ with her long, straight black hair, big blue eyes. I think they didn’t quite know how to take a baby that looked like that because then, as now, there was a spiritual, a Madonna quality about Elizabeth.

“Elizabeth, too, knows beauty can be a handicap. I’ve heard her say more than once: ‘Oh, I’ll be so glad when people stop writing about how beautiful I am and start writing, instead—I hope—of how well I can act.’

“Now she is nineteen,” her mother added then, “maturing in her work as well as in her personal life. Perhaps when she attains this maturity, all the unhappiness she has had, all the heartaches, will have been worthwhile, will enrich her.”

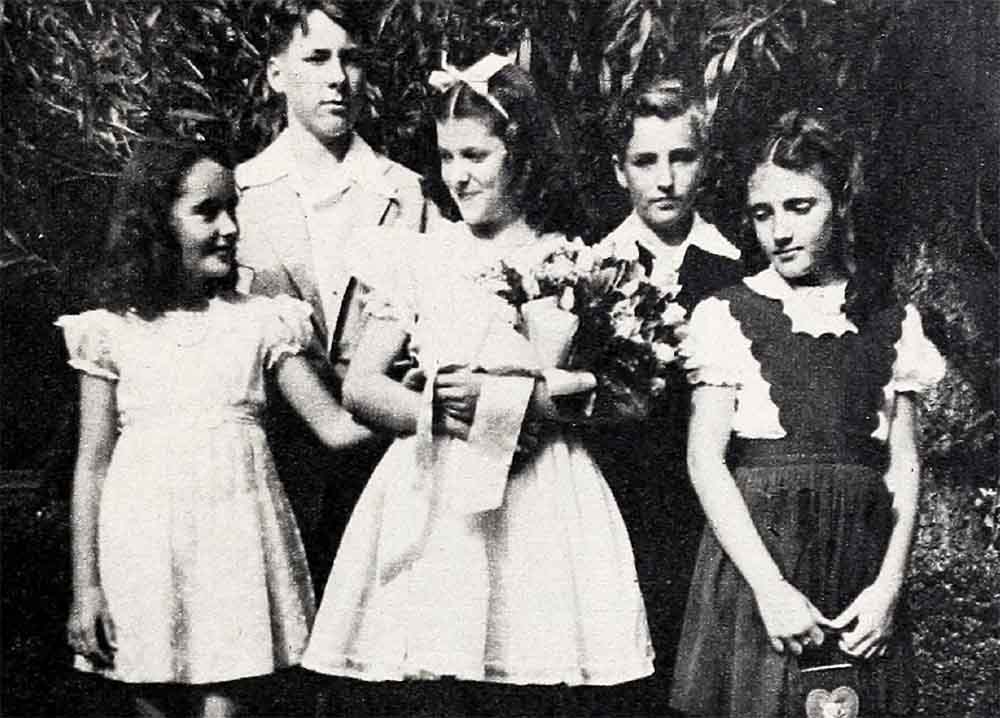

As a child, Elizabeth was shy, sweet and protective. Whenever her brother Howard, who was three years older than she, was caught at a prank, Elizabeth was there to plead for him. “He’s sorry, honestly he is.” Her brother’s silences could be stubborn ones. “Howard, please say you’re sorry.”

However, she was never lacking in ingenuity. When she and Howard went into the lemonade business and their sidewalk stand failed to stop traffic, Elizabeth simply skipped out into the street. She brought the cars to a halt long enough for her brother to make a sale or two and their business began to boom. The venture came to an abrupt end when Elizabeth stopped the wrong car. Their mother was behind the wheel and was quite properly horrified.

Her motion picture career began with much less effort, for in the years of growing up, Elizabeth had become the family beauty.

When she was ten, a friend of the family suggested that the Taylors take Elizabeth to M-G-M. When they walked into the producer’s office and introduced themselves, the producer took one long look at Elizabeth, excused himself and rushed from the room. He returned, accompanied by a half-dozen other executives. They, too, stood and looked at Elizabeth.

No one asked her to read lines or sing or dance or display any evidence of talent. They simply stared and then scurried to find a contract for her to sign.

Of those days, her mother says now: “If I could wave a wand and make them young again. These are the well-worn words which come to the lips of every mother. They come to mine. If I had it to do over again, Elizabeth would not be in pictures. I would not allow it. I think she has had so many heartaches she might not have had if she’d been just a girl at home. But, as is the way, I think, with parents of our generation, we always listened to both of our children, and when Elizabeth wanted to be in pictures and begged so hard, we gave in, mistakenly.”

“Elizabeth was never one of those impossible movie brats,” says William Tuttle, head of the make-up department at M-G-M. Tuttle can still picture her as the child who appeared in the department with her pet chipmunk, Nibbles, on her shoulder. “I never had the impression that Elizabeth was overtrained or that every move was studied,” Tuttle continues. “She was a very natural child. And she seemed to have a lot of the same quality that Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney have. I’d call it heart.

“Of course, the first thing I noticed was her beauty. But when I began to work with her, I became increasingly less conscious of it. I thought of her as a warm, sweet, nice little girl.

“Another thing I recall,” Tuttle adds, “is wondering, when she first came to the studio, just what would happen to her when she reached the awkward age. But she never did.”

Elizabeth was fifteen when she appeared in a movie called “A Date with Judy.” Moviegoers and critics alike came, saw and were captivated. Not by her dramatic ability, however, but by her exquisite beauty. One evening, as she curled up on the couch to study a script, she looked up at her mother. “Know when the most wonderful time will be?” she sighed. “When I get good parts and they say I was good in them—not just that I was pretty. If you feel you’ve done a good job . . . well, I guess you’ve sort of earned the praise and it means something. But I didn’t make my face.”

“Beauty, I believe,” her mother explains, “can be a great drawback. A handicap. If you are beautiful, it brings a lot of wrong thinking down on you. People think you are spoiled, lack brains, are vain, superficial. You are also constantly on exhibition.

“Elizabeth has never liked this exhibition. once, in Paris, when she was about thirteen,” Mrs. Taylor recalls, “we were shopping and a crowd of people gathered ’round, came close up to Elizabeth, poked at her with their fingers as at a china doll. And all the while Elizabeth stood there, at bay, cornered, miserable. After we got away, she said: ‘I wonder if people who come close to you like that have the same feelings that you have? I don’t believe they have or they would know how they embarrass you.’ ”

Elizabeth’s features were a gift; she had nothing to do with them. And as happens to so many beauties, the girl behind the face had begun the familiar cry: “Look at me, the real me—at what I can accomplish, the kind of a person I am inside.”

Some did look. “I met Elizabeth one evening after she and her mother had returned from a trip to England,” says one of her childhood friends. “The Taylors knew my folks and Elizabeth and Mrs. Taylor came over for dinner.

“I’d heard of Elizabeth, some time before. My brother had come home from Griffith Park one day and he was raving about how he’d just met the most exquisite creature he’d ever seen.

“When the Taylors came to call, I met one of the most refreshing girls I’ve ever known. Elizabeth was so honest and straightforward, and yet there was a shyness about her. One couldn’t help but like her.

“She had so few girlfriends. She’d had no opportunity to meet many, and she seemed to need someone. We became very close.

“Another trait I noticed long ago, one that she’s retained,” her friend continues, “is her lack of malice toward anyone. She wouldn’t and she doesn’t gossip. If the conversation is going that way, she never enters into it. She seems to find no fault with anyone, but she’s quick to find it in herself. And as for her social life, she still prefers to stay with little groups that she knows very well.”

As a youngster, Elizabeth could go to parties given by her friends and enjoy herself. But whenever new girls were included in the gathering, things went amiss. Some would gush over her, others would eye her with suspicion or envy, still others ignored her completely. There seemed no happy medium with strangers, and when Elizabeth got home, she’d report sadly, “Well, I did it again. Just stood around with egg on my face.”

Yet she was a typical teenager. She begged to wear lipstick. (“Mother, do you want me to be a square?”) More than anything else she longed for a black formal and a closetful of peasant blouses. (“Everybody has them.”) And there was the matter of costume jewelry—-the more the better, or so she thought, for a time.

One evening, the Taylors were hosting a group at their club. Mrs. Taylor, wishing to be on hand to greet early arrivals, left the house before Elizabeth was dressed. The party was already in progress when she next saw her daughter. Elizabeth was making an entrance, a mass of pearls. There were pearls in her hair, along with two false braids, pearls around her neck, pearls dangling from her ears. Her date had showered her with orchids and she wore them all. From her manner, it was obvious that she felt like a queen, and her mother sent up a silent prayer. “Please, don’t let anyone laugh at her. It would break her heart.”

The following day, mother and daughter had a talk about simplicity of dress. “Don’t you think that perhaps you overdid it?” asked Mrs. Taylor.

“Well,” said Elizabeth, taking mental inventory, “maybe.”

She longed for dates—but somehow the boys didn’t rush to beat down the Taylors’ front door with the enthusiasm one might imagine. Her brother Howard brought home his school chums and she did a few things with them. But, when it came to actual dates, Howard was reluctant to give aid. When the time came for a girl-invites-boy dance, Elizabeth approached him with a request. “Would you ask around and find out which boys have dates and see if there are any who don’t?”

“Why don’t you ask?” Howard replied.

“It would be so embarrassing to be turned down,” she wailed.

Howard assumed a pained brotherly expression. “I can’t go around quizzing every guy in school,” he told her. “You take your chances like everybody else.’’ And she did.

“She was so lovely that the fellows just couldn’t be as casual with her as with other girls,” says a friend who remembers that period. “And poor Elizabeth couldn’t understand it.”

For a time, Elizabeth had a crush on her friend’s brother. “Why won’t he ask me for a date?” she’d want to know.

Finally, her friend approached brother. “Can’t you take her out sometime and be nice to her?”

Thus began a heart-to-heart talk. “Sure, I could take her out. But how could a guy be casual with a girl like that? Elizabeth’s the kind of girl any man could fail in love with in a hurry. And she’s still a kid. Would you want a child bride for a sister-in-law?” he finished with a grin.

For his explanation, brother got a couch pillow thrown at his head. But his sister understood, and she didn’t ask again.

Elizabeth was destined to be classified a heart breaker soon enough. When she was seventeen, two friends from M-G-M brought the West Point football star, Glenn Davis, to the Taylor home in Malibu for the day. Elizabeth liked him better than any boy she had ever known. When Glenn went to Korea, she wore his gold football on a chain around her neck. When he returned, she was on hand to meet him. “I was devoted to him,” she said later. “It was a phase. I got over it.”

Every girl has a right to a romantic phase—unless she’s Elizabeth Taylor and one phase is followed by another. There was Bill Pawley, to whom she was engaged. Many a girl has broken an engagement, but few break-ups have been accompanied by so much publicity.

Then there was Nicky Hilton. They were young, too young, attractive, both had been given everything their hearts desired. And now, they decided, they wanted one another. They dated for eight months, to be certain. And on May 6, 1950, Elizabeth walked down the aisle with the happily-ever-after dream of every girl. Perhaps it was only a dream that each of them had loved. At any rate, it soon tumbled. Seven months later, confused and disillusioned, Elizabeth filed suit for divorce.

Her face grew thin; it was still beautiful, but it was haunted by bewilderment. “Look at me, the real me,” the child had pleaded. But who was the real Elizabeth Taylor? What kind of a person was she? She thought she had known. Now she wondered if anyone ever really knew. “I thought I was mature enough to cope with marriage,” she said. “I wasn’t.”

She returned to her parents’ home for a brief time, then she decided to find an apartment of her own. She was no longer a child, but she was not yet a woman. “It’s time I grew up,” she admitted. “I never knew responsibility and I can’t learn it under someone else’s wing. If I make mistakes, I’ll learn something from those, too.”

She didn’t want to be entirely alone, so she set out to look for a secretary-companion. Her agent’s secretary volunteered to call a friend, Peggy Rutledge. “Would you like to work for Elizabeth Taylor?” Peggy was asked.

“I don’t know,” came the reply. “Is she a nice person?”

“I think you’ll like her,” said the secretary. “Come and meet her.”

Peggy went to the agent’s office for the interview. When she and Elizabeth had been introduced, the agent and his Girl Friday left them alone together. There was a lengthy silence before Elizabeth spoke up. “I don’t know what to say,” she began.

“I don’t either,” said Peggy. “I’ve never done this before.”

There was another pause. “Can you make coffee?” asked Elizabeth.

Peggy grinned. “If I’d known you at all I’d have brought a thermos from home to see if I could qualify.”

“Why don’t you go look for an apartment for us,” said Elizabeth. “When you find something you like, let me know and I’ll come see it.”

An apartment found, they moved in. They stayed until the following July, when they went to England where Elizabeth was to make “Ivanhoe.”

“A couple of days after our arrival,” remembers Peggy, “a man by the name of Michael Wilding called. Elizabeth didn’t want to go out with him by herself and asked if I’d like to come along.

“We went to dinner at a place very much like an American restaurant, then afterwards on to a place for dancing. Elizabeth and Michael had met before, but at the time he’d thought she was entirely too young for him. It was soon pretty obvious that he was in the process of changing his mind. They danced until six in the morning on that first date—and Michael doesn’t especially like to dance.

“They had several dates, then Michael left for a vacation in the south of France. He telephoned her from there.”

Elizabeth was glowing when she hung up the telephone. “There isn’t a phone where he’s staying,” she reported. “He had to go miles to make the call. Oh, Peggy, wasn’t it sweet of him?” She glowed some more, and settled down to wait for Michael’s return.

“By the time she left England,” says Peggy, “she was madly in love with him.”

Elizabeth had arrived in England, restless and unhappy. She left a different girl. “I was always searching for something, and I never knew quite what,” she said later. “But now I know. It was love. Real love.”

Elizabeth had to grow up for Michael Wilding. She had to find herself. In doing so, she found a serenity that amazes her husband and her friends. “It’s made her warmer,” they say. “More outgoing.”

She also found courage—and she used it well when her eyesight was threatened by a Steel sliver that flew from a wind machine on one of the sets. There were two operations. She knew she might lose the sight of one eye. “Everyone else was frantic,” says her friend, designer Helen Rose. “Elizabeth knew the danger, but i she took it so calmly—as if it were simply a mild ailment, and everything would surely come out all right.”

She found the ability to laugh at herself and at the jibes of others. She was the first to laugh when, at a party, someone eyed the maternity dress she’d worn I to several events and meowed, “Is that all you have to wear? It’s really getting to be a uniform, my dear.”

She found new interests—books, interior decoration. “Michael’s always given me a free hand when it comes to decorating our homes,” she says. “I let the colors run riot in the first one, and he never said a word. Eventually, I learned and our new home is far more subdued—and more attractive.”

She’s found contentment in her home, in puttering around the kitchen occasionally or, better yet, looking on as Michael prepares a meal. Michael’s meals are never dull, and they’re real productions. He’s been known, in a moment of desperation, to call the author of his favorite cookbook, to clear up a culinary point i that puzzles him. But he turns to his wife as an authority on Identification of kitchen utensils, when on such a project as split-pea soup. “Elizabeth, what does a sieve look like?” She told him. “How do I get the peas through it?”

In the four years she’s been married to Michael, Elizabeth’s career has taken on a new purpose. Before, she cared about so few of her roles. Now she wants to prove herself with each new part.

“I’ve never seen anyone work so hard,” said producer Henry Ginsberg on the set of “Giant.” “The Texas location was a rough one. It was hot, dusty. The players got up before dawn to go into make-up and make the drive out to the set. And they didn’t come back until dark. We thought if anyone would fold it would be a fragile girl like Elizabeth. But she took it best of all and never missed a night of studying the rushes.”

Since the birth of her two sons—Michael, Jr., in January, 1953, and Christopher, in April, 1955—Elizabeth’s life has taken on new purpose. “She’s a natural mother,” say her friends. “When little Mike was born, you’d have thought she’d already had six kids.”

Making pictures on location has occasionally taken Elizabeth away, but evenings always finds her by the telephone— as one evening in Texas. “Chris wasn’t talking at the time,” she recalls, “but Mike, Jr., was making up for his brother’s speechlessness. ‘When are you coming back? Are you coming on a plane? I love you, Mommy. I miss you . . . pretty Mommy.’

“Michael, you were coaching him,” Elizabeth accused her husband when he took the receiver from his son’s hand.

But “pretty Mommy” wore a smile that was something to behold. And she’d never looked lovelier. For her husband, and now her oldest son, had taught her a lesson she was fortunate to learn. Elizabeth is loved for what she is—wife and mother—not for what she looks like.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1956

No Comments