The Grangers Call It Love—Jean Simmons & Stewart Granger

“Cough once,” said Granger. Jean coughed like an ailing butterfly. “Cough big!” She coughed big while he leaned from his height to bend a judicial ear.

Flu had felled her on the set of Desirée. Just out of bed she was bound for the doctor’s. “You think I’d better go back to work tomorrow?”

“Over my dead body.”

“Why?”

“Because I’m bigger than you are.”

Though the day sweltered, even on their sky-reaching hill, Jean was winter-clad. A scarf tied snug under her chin. A dark wool slack suit covered her from throat to ankle. She looked small and woebegone, a bunny huddled against nameless perils. To ward them off, she clasped her husband’s waist, dug her head against his chest. His arm went round her. “Can I have some moola?” she asked, piteous.

The other hand fished out bills. “This one? Or are you planning to take a boy friend out to dinner?”

She plucked the larger one. “I’m a gold-digger.”

“Come along, gold-digger. The taxi waits.”

This homespun domestic scene left a pleasure feeling as of bells rung in tune. It’s a tune that has always sounded good to the Grangers. For reasons hard to assess, Hollywood seems to enjoy playing it jangled.

Consider last winter. Granger works for MGM. By and large, although with an occasional struggle, he goes where they send him. They sent him to England to make Beau Brummell. Jean stayed behind. Columns, having subsided for a while, broke into new and fevered rashes. He was sore because she’d refused to go along. She was sore because he’d left her flat. While she moped at home, he was living it up with the Wildings. Even—tsk, tsk—dating Elspeth March, his ex-wife.

So much for creeping innuendo. Now for the facts. With more weariness than ire, being past ire, Granger lays them on the line. Yes, he saw Elspeth March. “She’s the mother of my children. We had matters to discuss concerning their welfare. I also happen to be fond of her. So is Jean. We’re rational people. That Elspeth was once my wife doesn’t now make her my arch enemy.” The Wildings, baby and all, shared his apartment. “If this be living it up, make the most of it.” As to who got sore, his look said louder than words that some asininities sink too low for comment.

Jean stayed behind for the same reason he went. She had to—by the terms of her contract with Hughes. In the hope that she’d be able to join him later, Granger took what he calls a woman’s apartment. “Double bed, silk sheets. Wouldn’t be caught dead in it by myself.” At the last minute she was shoved into a picture. “Which was rather worse than saying goodbye, period. Knowing it’s for months, one steels oneself. But this other sort of teasing thing—she’s coming, she’s not, she’ll be here, she I won’t—that’s murder. Someone else said it more tastefully. ‘Hope deferred maketh the heart sick.’ ”

It’s true that he kept her in tears while he was gone. By his own peculiar methods. When she was sixteen, Jean’s father died, but he remained a living part of her life. “You loved him so dearly,” said her husband. “I can’t understand why you don’t have a photograph of him.”

“Mummy’s got the only one and she won’t let me have it.”

This offered no insuperable obstacle. In England he asked Mummy for the photograph, vowing to guard it with life and honor. As she went to fetch it, he insist he grew panicky. “I’d heard so much about him. Suppose I hated to look at his face!” The face was strong, sensitive, beautiful. He stared for a good two minutes and paid tribute. “No wonder she loved him.” He had it enlarged and framed, reproduced in sizes small, big and various—tor a billfold, a locket, a dresser—sent them all to Jean. From having no picture of her father, she was suddenly surrounded. She cried.

The trip was something she’d hungered for. “I want to walk up the London streets,” she moaned, “and get lost in the fog and smell the Thames. I’m homesick for London.” The cry echoed in Granger’s ears. By good chance, he met an artist who specialized.in London scenes—fabled places like Fleet Street and The Mall. With a certain diffidence he broached his scheme, which involved a tiny little street in Hendon. “Its artistic interest may be nil. It’s not very beautiful except that my wife was born there. Would you go down and draw it for me?” The artist obliged, delivering his sketch to the studio. The cameraman on Beau Brummell, an old friend of Jean’s, took a look. “Very nice,” he said, “only she wasn’t born there. Family moved to Hendon when she was three. If it’s her birthplace you want, go to Holloway. Right near the Holloway Jail. Wonderful old pub on the corner. You’ll like it.” Both sketches flew the Atlantic, arriving on that strategic day when Jean’s hope of joining her husband was finally quashed. She cried again.

Let’s concede there’s nothing noteworthy about a man’s thoughtfulnes for his wife. It does, however, indicate sound relations. Yet the snipers snipe, taking what seems to be almost gleeful aim at the Granger marriage. They can do it no real harm. But when the peppering grows so heavy as to bring phone calls from Jimmy’s mother in England, it acquires nuisance value. It also begins to bore those who hold no personal stake in the game.

Granger is the target, not Jean, Jean is the martyred darling. (A darling she is, though singularly unmartyred.) What makes him a target is what we profess to admire—individualism. He refuses to be—more accurately, he’s incapable of being—anyone but himself. In many communities, life goes more smoothly if you’re cut to a pattern. Granger isn’t.

He’s a fighter for one thing, and fighters risk treading on people’s pet corns. When his spirit yells no, you won’t hear his mouth mumbling yes. His are honest battles over issues he honestly believes in—be it a script that seems ill-suited to himself, a contract he considers one-sided or further lengthy separations from his wife. Returning from five months in England, he delivered an ultimatum. “I won’t leave Jean again.” “Sorry, old boy,” they told him, “but you’re going to South America for Green Fire. Relax, it’s only two weeks.” He stood his ground, and collision threatened. Though you may have heard hints to the contrary, studios are often human and Granger is reasonable. They pared the two weeks to six days. Granger went.

Moonfleet, which he’s making here, presents no problems. But a cloud lurks over the horizon. They want him to do Bhowani Junction in India. He’d be all for it—if Jean could play the girl. “Or even if they’d let her do a film in Burma,” he suggests dryly. “At least we could nip across and see each other. It’s this awful sensation of 8000 miles between you that’s soul destroying. Cables and phone calls don’t help much. Hang up the phone and you’re lonelier than ever. Not that I’m blind to MGM’s viewpoint. We’ll have to work it out together, that’s all.”

This hardly sounds like the mulish truculence with which he’s sometimes charged. That he’s no Job for patience he’d be the first to grant. Inefficiency irks him. His standards of workmanship are high. He won’t sacrifice them on the altar of popularity. Universal popularity doesn’t head the list of things-he-can’t-live-without. Hollywood is an open-armed town, where yesterday’s stranger is tomorrow’s darling. Not so with Granger, a Britisher and a Scotsman, to boot. If one Britisher is more self-contained than another, it’s the Scot. Those friends he has and their adoptions tried, he keeps for life. Easy intimacies fail to attract him. “We ask people up here because we want to see them, enjoy talking to them. You can’t talk to four hundred at once. So we have six or ten or even two. What’s wrong with that?” The answer, of course, is nothing. You like big parties or you don’t, and neither inclination is a subject for censure. But tell that to the critical, who tag him snooty and bewail the fact that he won’t even take poor little Jean out dancing. Poor little Jean feels no pain. True, she likes dancing and he’s tepid about it. “It’s a difference,” she points out, “not a yawning abyss.” He recognizes the difference. Often as not, he’ll strangle his reluctance. “There’s this little jive joint somebody told me about.” (Both prefer little jive joints to glamour clubs.) “Come on, you can dance your head off.” Often as not, she’ll be the one to protest. “Darling, I’m tired. Anyway, Groucho’s on tonight.”

Others may cavil. His wife feels not the slightest yen to change him. She’s purringly content with him as he is. They talk the same lingo, the same kind of nonsense exhilarates them. Where Hollywood is effusive, they thrive on understatement. Any public display of sentiment makes them squirm. “In simple affection,” he explains gravely, “we call each other idiot.” If she does it, it’s cute. It he does it, eyes glaze and paragraphs get into all the papers. “What Granger said!” Most are perceptive enough to realize that one man’s “idiot” can hold more tenderness than another’s glib “sweetheart.” But they need fillers.

All stars are subject to similar forms of attention. It’s the price they pay for stardom. No marriage within memory has been so constantly assaulted on such flimsy grounds. Take the oversize house he bought on arrival. He had made a mistake, rectified it, paid for it with his own hard cash, and whose business was it anyway but their own? Yet the town sliced it up until it sounded like a misdemeanor, if not a slight felony perpetrated against his bride. Take Jean’s early unhappiness in her work, which sometimes reduced her to tears on the set. These were promptly translated into rows with her husband; why else should a girl weep? Take home economics. He’s handy with a skillet. She’d rather go hungry than fix herself a meal. Domestic details aren’t up her alley. He can manage them with a twist of the wrist, and does, seeing no reason to impose on her distasteful burdens. This is bad? Apparently. Why? Because he’s invading her realm, robbing her of her feminine right, treating her like a child. Take even the matter of a couple of TV sets. How can they love each other when they watch different programs? Yes, it gets that silly.

They’ve been under fire along other fronts. But here, at least, they’re in company. No British actor has ever drawn a Hollywood salary check without being prodded, more or less gently, on the subject of American citizenship. Some ignore the prodding, some react off the record. Ask Granger a straight question, and you get a straight answer. “I’m forty years old. I’ve spent nine-tenths of my life in England. I have two children, a mother and sister there. Jean has a mother, a brother and two sisters. Our roots are there. You can’t tear them up because you’ve worked elsewhere for three years. Put yourself in the same position. England means to us what America means to you. If we changed citizenship now, any thinking person must know we’d be hypocrites, acting through shabby motives—to help us over taxes, to make travel easier on an American passport. This would be an affront to America, not a tribute. Hollywood has given us a lovely way of life on this hill. But obviously it’s not the American way. We don’t know enough about America to form opinions. Later, perhaps, especially if children were born to us here, we’d make it our business to travel up and down the land, study it, learn it, and become citizens, if we did, not as a convenience but because we loved it and wanted to spend the rest of our lives here.”

They hope to have children, though not yet. Through her former contract, Jean’s career stagnated. Now it’s blossoming again. She’d like to concentrate on it for a while. “We don’t believe in turning kids over to nannies. That way, you have a little thing in the house and never get to know it. Baby cuts his first tooth on Nanny’s finger, takes his first step and topples into Nanny’s arms. All agog, she phones Mummy at the studio. Mummy wails to high heaven, feeling cheated and with good reason. When Jean becomes a mother, she’ll do one picture a year.”

Their work has kept them apart more than they like. In three and a half years, they’ve had no time for a holiday together. Last summer they planned to go to La Paz. Green Fire was due to finish the first of the month, Desirée to start on the sixteenth. Reservations were made, fingers crossed, eyes fixed on the promised land. Then Green Fire dragged on through the twelfth and La Paz went a-glimmering. They sighed and swore, each according to his gender, and resigned themselves. The twin career holds no terror for them.

“What,” demands Granger, “would I do with a woman who’s never known the exhaustion of a day at the studio? What would she do with a man who wants only to flop and put his feet up? Words, I imagine, would flow like Niagara, and words have been known to lead to drastic action. Jean and I understand without too many words. We’ve been pricked by the thorns of the same profession.”

With an adult outlook, each respects the other’s need for fulfillment in work. Granger’s masculinity doesn’t require the prop of a little woman dancing attendance. So long as Jean wants a career, hell encourage her in it because of the bred-in-the-bone conviction that every person has the right to express himself in his chosen way. In acting, she has found her medium. He hasn’t.

Physically equipped as few men are to play doughty heroes, doughty heroes give him a pain. “They’re dull creatures. Nor do I consider that by donning a wig and sword, you achieve anything much.” Here too, however, he sees the studio’s viewpoint. His derring-do films bring home the bacon. “And who’s to argue with bacon? Yes, I’d like to slip out of ruffles now and again into the skin of a real character. But if I don’t fight too hard for a change of pace, it’s because I’m not all that keen about acting. Acting leaves me feeling fenced in, a little frustrated. I fancy myself creative along some line.”

His far-from-secret goal is to be a director. Although it’s a serious ambition—more likely, because it’s a serious ambition—he kids it. “I’ve yapped about it so much, I’ll probably never do it. In which case, I can always tell my grandchildren what a fine director their granddaddy might have been. Better than maybe risking the ghastly chance that you’re lousy.”

Director or no, he’s bent on owning a farm, getting down to such basic creative activity as crops and calves. Jean stipulates only that none of the calves shall ever be sent to market. Meanwhile they pursue their lovely way of life on the hill. “Lovely to us,” says Granger, “and dismally unspectacular in the telling.”

Since his return from England, something new has been added in the person of Rushton, who used to work for him over there and agreed to temporary transplantation. A quietly glowing gem, Rushton runs the household, does the marketing, rises virtually with the dawn to fix Jean’s breakfast when she is working. Which ought to leave Granger slumbering undisturbed. Only it doesn’t. “When Jean gets up, nobody sleeps. For a small girl, she makes disproportionate noises. She falls down, she trips over things. I hear her mutter ‘Excuse me’ to the bedpost, ‘I’m sorry’ to the door.”

“Creative fancy,” says Jean, returned from the doctor’s now and comforting herself with a spot of tea. “Some day he’ll stick that bit into a movie.”

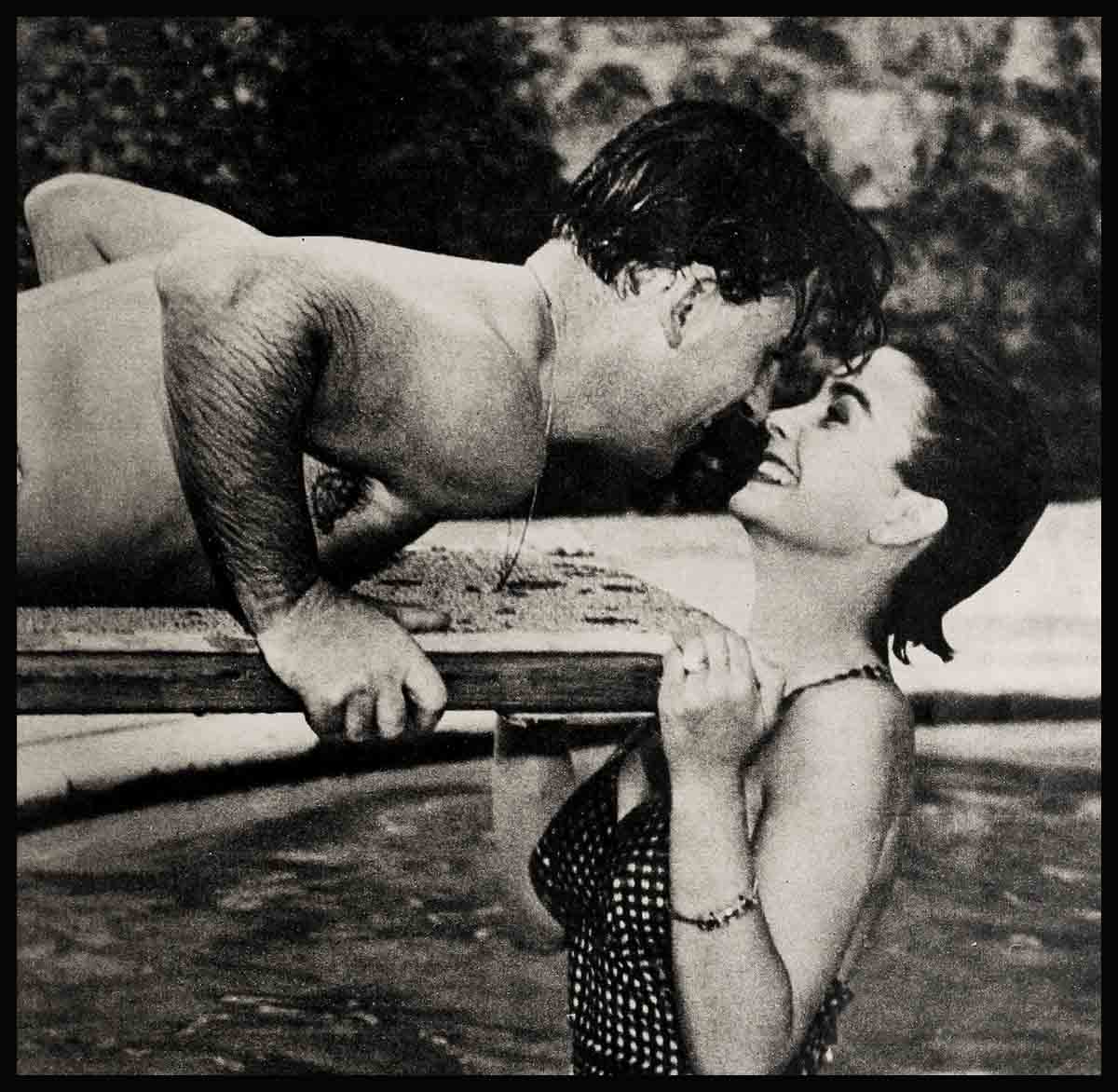

Hendiess, he plunges on. “Whereas my wife can sleep through thunder, earthquakes and dogs licking her face. On those rare mornings when we’re both unemployed, Rushton brings in the coffee. I drink it, with this dead body beside me. I shower, I dress, I go out and putter round the garden. Contrary to printed report, I do not uproot trees with my bare hands. My horticulture consists in meditating on what to tell the gardener to do next. I change into trunks. I take a plunge in the pool. By now it’s ten, so I look in on my sleeping beauty. She continues to lie motionless. I drop a heavy object. Nothing happens. I grow uneasy. I clunk her over the head three or four times.”

“With a soft hammer,” she prompts. Then they eye each other. “Uh-uh. Somebody might believe it. Delete jokes.”

“Hammer deleted. What I actually do is open the door to the clustered animals and let them climb over her.”

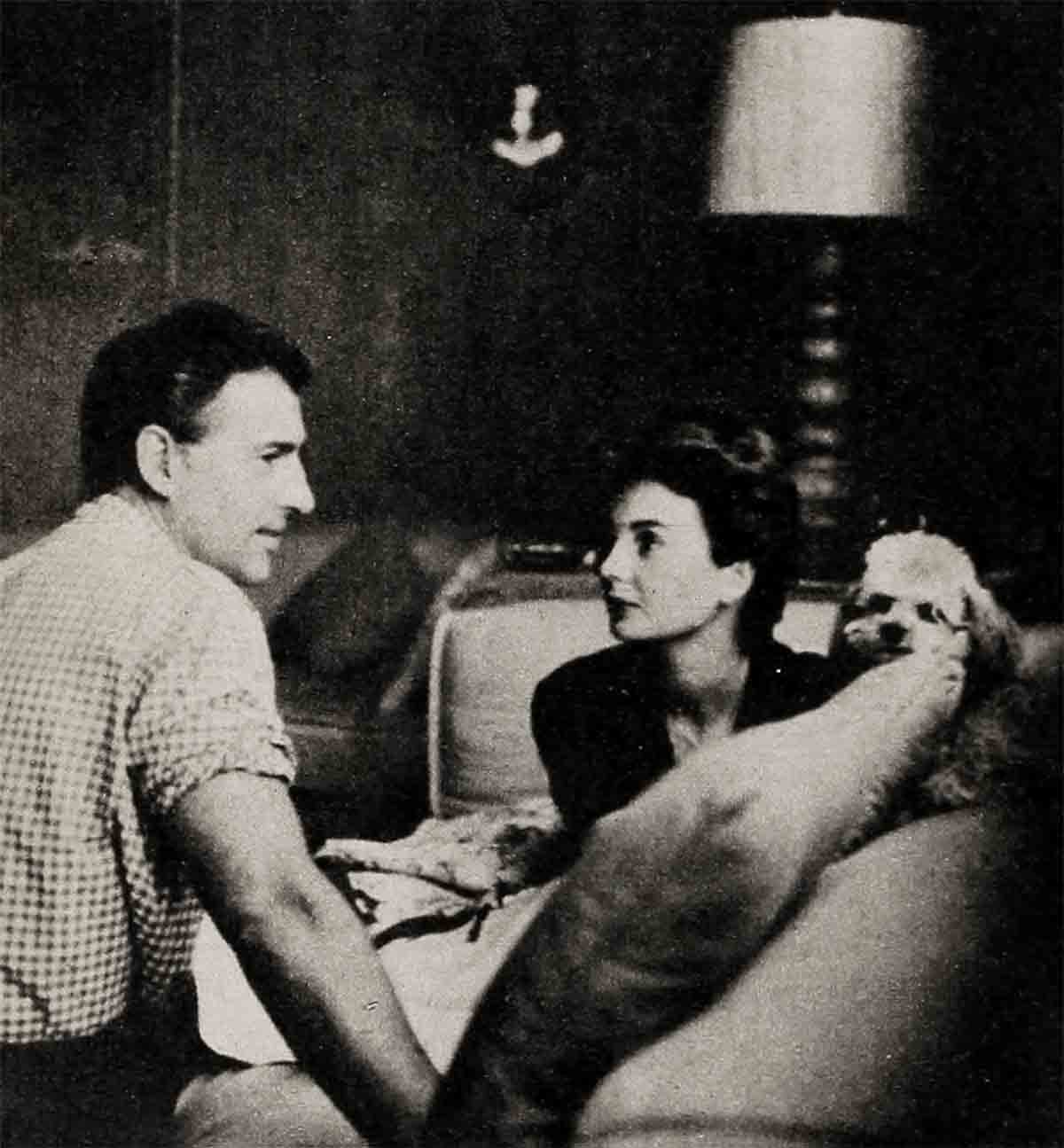

The animals number four. Two cats called Traybert, in combined honor of Spencer Tracy and agent Bert Allenberg. Two miniature poodles—Young Bess from the movie of the same name, Old Beau after Beau Brummell. Granger is this kind of despot. Jean says: “I would like a cat.” He says: “Darling, you don’t want a cat,” and orders a couple of Siamese.

Finally dragged from unconsciousness, Jean breakfasts in bed with the newspapers. “She’s a diligent reader. First, the funnies. Every picture and word of the funnies from stem to stern. Then the columns. If she’s mentioned, she yells. If I’m mentioned, she yells. If a friend’s mentioned, she yells, though not quite so loud. If she devours them in silence, it’s a sign that nobody she knows got a tumble that day. I’m not sure whether she’s relieved or disappointed.”

“A smidgen of both,” she tells him.

They putter some more, they inspect their once barren hillside, now blooming like paradise. They bask in the sunlit hours of a lazy day. “How can you itemize them?” he asks, forever astonished that anyone should be interested in the trivia of their daily lives, but doing his best to oblige. Friends may drop in. Their reputedly British circle is liberally sprinkled with Americans—Tracy and Allenberg, Garland and Luft, directors Cukor and Kazan. Jimmy cooks up some dinner. Jean hovers. The culinary arts fascinate her at a distance. She eats what he gives her, criticizing all the while. “This meat’s too well done. There’s not enough pepper.”

“Shall I hand in my notice, madam?”

“I’ll think about it. Ask me in fifty years,”

When they’re alone evenings, TV holds them enthralled. “Being competition, it makes us feel slightly guilty. We swallow our guilt and tune in just the same.” He’s mad for baseball and the fights. She plays her own favorites, then wanders over to him. Baseball she likes. “Unless the blokes paste each other too hard.”

“Then she ducks. Our attachment to TV stems less from the programs than the sociability. It’s cozy lounging together on the couch with a bottle of beer in your hand. You watch the Rheingold commercial and take another slug of Budweiser.”

“For that remark Rheingold will doubtless crown you.”

“It’s a typographical error. It’s also time for you to pop back into bed.”

We caught a final glimpse of them in the doorway. Bess’ tufted head poked out of the nest of Jean’s arms. Looking for something to chew, Beau took a sniff at Jimmy’s shoe. The Grangers, big and little, stood close. They stand close in more than the literal sense. They’re nice people. They’re happy. They love each other. Let’s leave ’em be.

THE END

—BY IDA ZEITLIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1954

No Comments