It Will Be… It Must Be… It Has To Be A Boy!

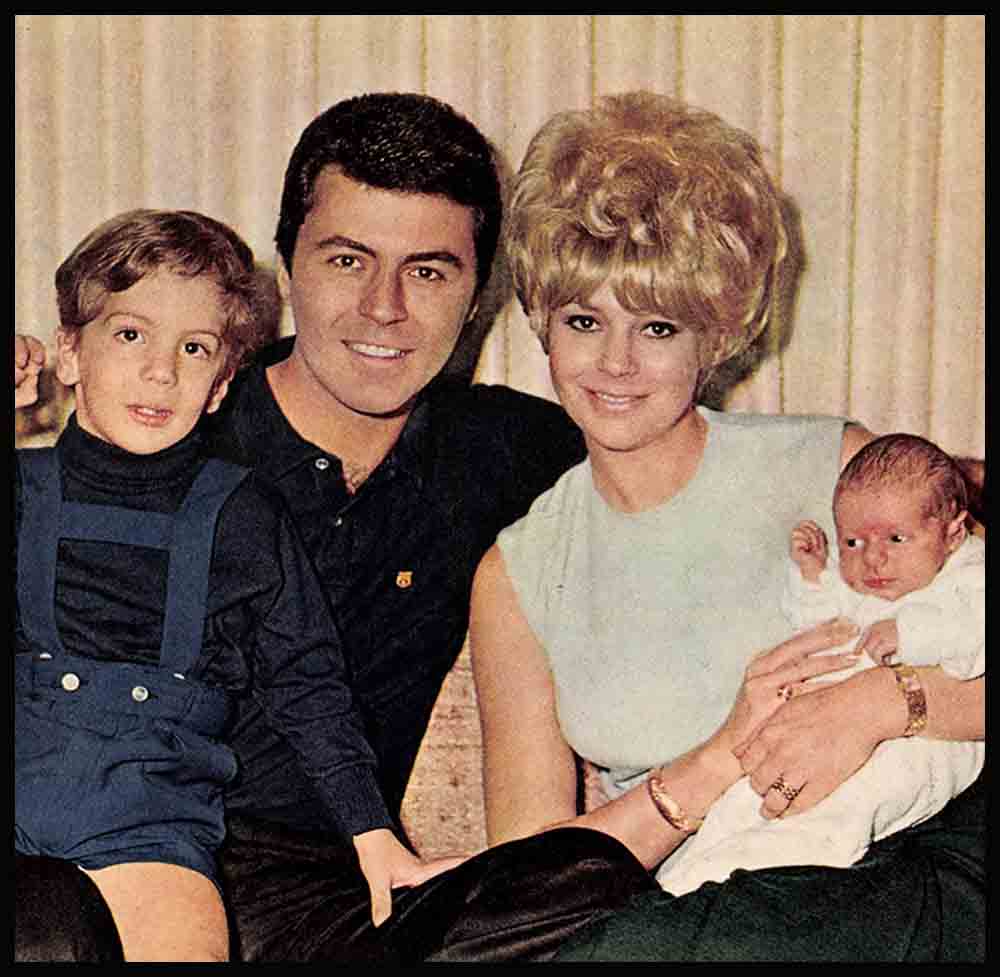

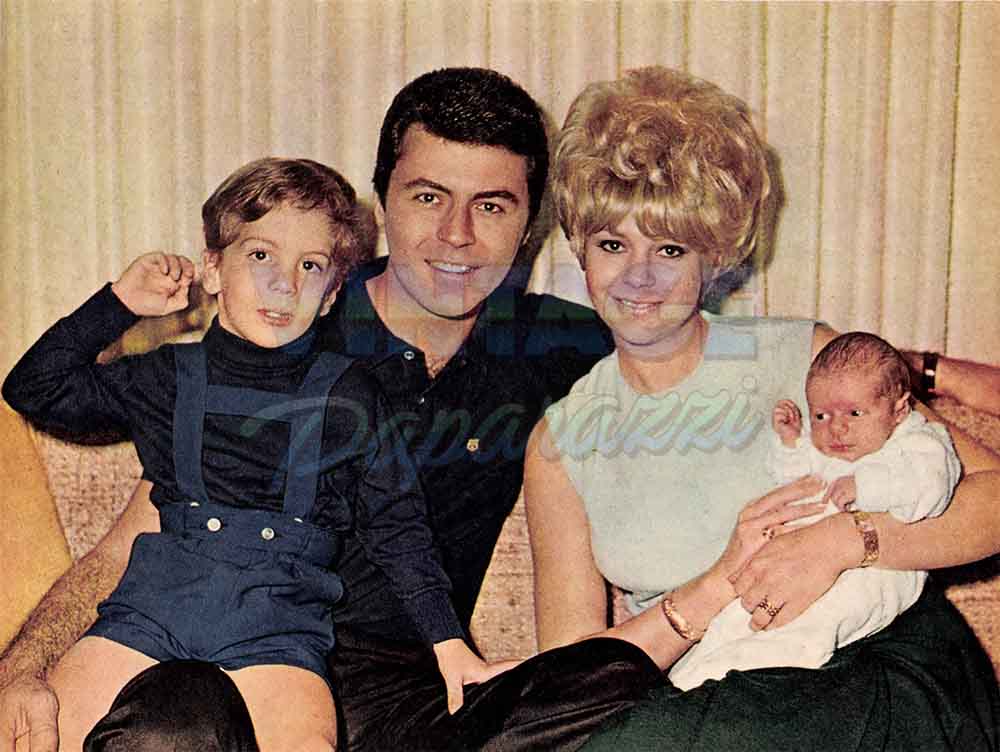

Anthony James Ercolani was born at 1:36 A.M. Thursday, December 5, 1963. Jimmy Darren, driving his wife to the hospital just before 11 P.M. Wednesday night, felt surprisingly frightened. Normally a silent man, he talked continuously during the forty-minute drive.

‘‘Are you all right, Evy?” he kept asking—as though she were actually in labor and in pain. And when he had to stop for gas, he damned the delay although there was no reason to hurry. Once he quarreled with her over a name for the baby, and several times he asked, “It will be a boy, it must be!” “Of course,” Evy answered each time. “It has to be a boy, Jimmy.”

They had known for a month that the doctor intended to induce labor, but neither of them had expected that it would be “tonight because it’s a nice quiet night at the hospital.” After the doctor phoned, Darren turned off the TV set automatically; and into the silence Evy had whispered, “l’m scared.” But there was no alternative. She dressed, packed a suitcase, and awakened Christian to tell him that “Mommy is going to the hospital now to get the new baby.” Fuzzy with sleep, Christian seemed little more than a baby himself as he lay in her arms, his feet clinging to her bulging waist. The last thing she saw as she left the house was Christian waving solemnly from the window.

“Are you all right, Evy?” Darren asked again, and he knew her well enough after four years of marriage to be reassured by the way she touched his hand. He smiled and concentrated on driving his Porsche through the late evening traffic. Five years ago, when he was just beginning to make money from his acting, he had walked into a foreign car showroom with $4,000 in his hand. He had known what he wanted—a white Porsche with red upholstery. The dealer was sorry. There was only one Porsche available, a black car. Darren had hesitated a moment. Then he had tossed the money down and said, “I’ll buy it.” It was in that black Porsche that he and Evy spent most of the year of their courtship. He had picked her up in the early afternoon each day and they had driven for hours, sitting silently in the car together, wordless, not even their hands touching. Eventually, Darren would turn to her and ask, in his angry way, “Are you bored? Do you want me to take you home now?” And she would always answer, “No, Jimmy.”

This was a different Porsche—a white car with red upholstery. He would be selling it in a few weeks because a Porsche was too small a car for a man with three children. It was strange how little the thought of selling the car bothered him, although—since his sixteenth birthday—fast cars have been his way of evaporating the overpowering angers he often feels.

He did not drive fast—nor carelessly—that night. When they reached the hospital, Evy waited with him while he parked the car. Then, slowly, they walked the two blocks to the hospital. Once inside, they wandered, lost, through the corridors for ten minutes be- fore someone directed them to the maternity floor. İn the elevator he asked, “Worried, Hon?” She shook her head. “Not too much, Jimmy.” He reached for her hand. They have never said too much to each other. They are both quiet people, inclined to moodiness. When their marriage survived a three-week trial separation a year ago, it was not because they “talked out” their difficulties. They just realized that it was hopeless for them to ever try to live apart.

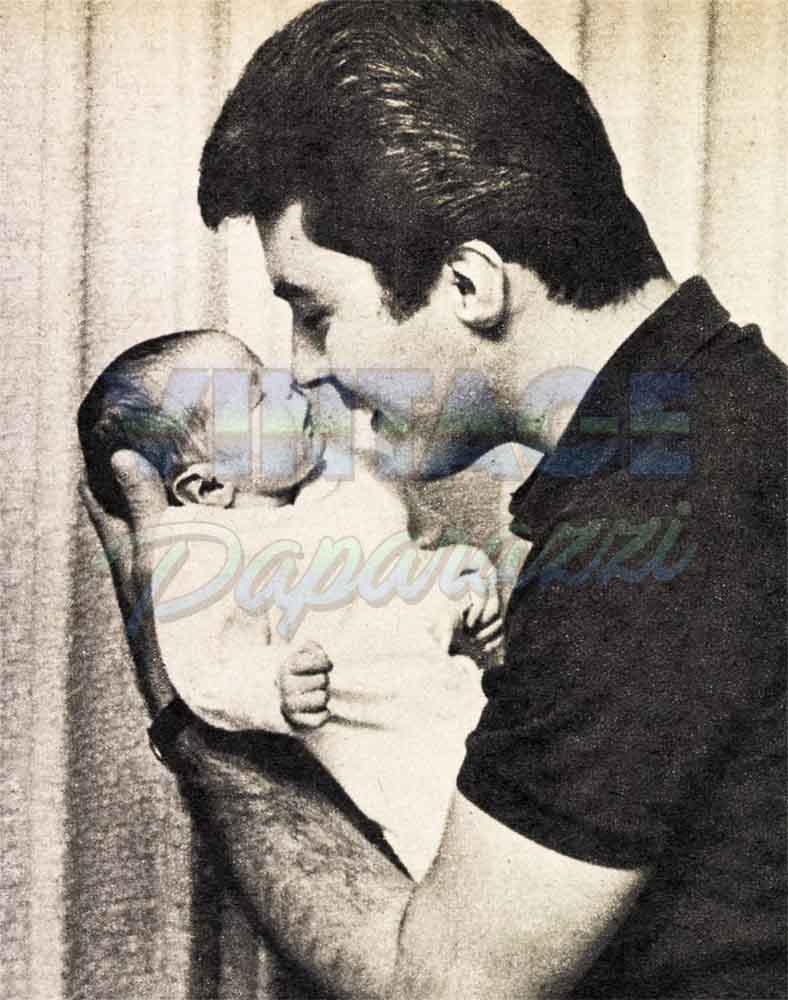

At the labor room door, the doctor bet them a Coke the baby would be a girl. His X-rays had indicated a girl, he said. Then he sent Jimmy home “because it will take three or four hours for labor to start”; and the door of the labor room closed behind Evy. There are moments when pain is so all-encompassing that the doors of the mind are shut to everything else. During the next hour and a half. there were many of those moments for Evy. There were no moments when Darren was unaware of his wife. He went home and changed his clothes. He had not quite finished buttoning his clean shirt when he was telephoned by the doctor to return to the hospital immediately. He reached the delivery room door at 1:35 a.m., fifty seconds before his son was born. He’d made fast time.

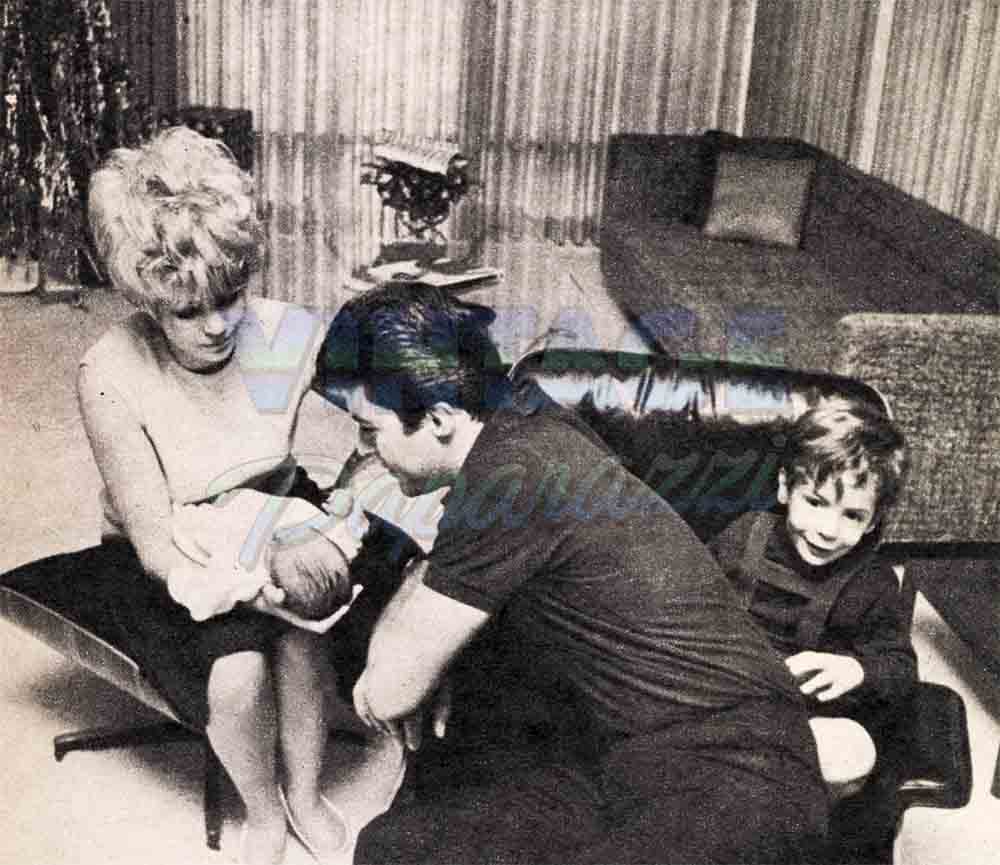

For Evy. there was pain. exhaustion. a moment of triumph when Anthony was born, Jimmy’s tingers stroking her hair, and then a drugged six hours of sleep.

Still lving on the delivery table and already half-asleep from the anaesthetic, she told him, “We have a boy. Jimmy.”

“No.” he teased. his mouth hidden behind a white mask “we have a little girl.”

“That’s right.’ she said. sleepily slurring the words. “we have a little girl.”

“No, no.” he insisted, angry at himself for his teasing. “it s a boy. Evy. A seven pound boy. We have another son.”

But she was already asleep and couldn’t hear him.

He kissed her sleeping lips. For James Darren, there was only triumph.

When Jimmy. his first son, was born six years ago, James Darren was terrified. He was twenty-one years old, one-half of a mixed marriage that d id not have the approval either of his own Catholic parents or his wife’s Jewish parents. He and Gloria thought that their love was enough. But—of course—it wasn’t. When Jimmy was less than two years old. they were divorced.

When he and Evy had Christian, three years ago, Darren was just as terrified. He had been married to Evy nine months and one week when Christian was born. It had been nine months of shifting their home from Los Angeles to Greece to London to New York and then back to Los Angeles barely three days before Christian was born. It had been nine months of quarrels and tension and exhaustion. When he held Christian for the first time, all he could think of was his three-year-old son who no longer recognized him, and he could only ask himself bitterly if he was trading in a used model son for a new one.

When Anthony was born, there was triumph.

At twenty-seven. Jimmy Darren is—for the first time in his life—satisfied. He wears his graying hair proudly, boasting that “Four of my uncles were prematurely P gray. One of them even had completely white hair at twenty-five. I refuse to let the studio dye my hair now. It makes me look mature. and I like it. It feels good.”

He sprawls in a chair, defenseless. A year ago, he sat tensely, ready to spring at a danger that might come from anywhere. Today he feels there is no danger, and the sullenness that has always distorted his handsome Italian features has disappeared. He seems relaxed, amiable, and—if not overflowing—at least half-filled with the milk of human kindness.

“I don’t think I ever felt more secure personally,” he says. “It’s incredible, being fortunate enough to have a family like the one I have. I’m an old man. I’ll be twenty-eight soon. That depresses me. People want so many things to happen, and time passes and the things don’t happen. But sometimes you have something to show for time. Like children.

“I’m easily satisfied right now. My career is important as a means of supporting my family and as being the only way I would like to support them. But if I suddenly lost my career, I wouldn’t go to pieces now. I’m better able to face reality than I was a few years ago.

“Sure, I want to get ahead fast. Sure. I want to be a star. Evy says, ‘You’re not a leading man yet. Jimmy,’ and she’s right. In this chewed-up business, a man rarely becomes a star today before he has the maturity that comes around the age of thirty. I can wait. What I want to do is just keep busy until then; do as many pictures as I can so long as they’re not trash; make as much money as I can and invest it for security; and enjoy my life. It’s all I can do. I can’t just go out and become mature.”

The ironic thing is that he has done exactly that during the four years of his second marriage. Most of the lack of tension that is so startling a part of him now comes from having solved some of the difficult problems of being alive.

When Darren returned from ten months in Europe three years ago. he found a three-year-old son who did not recognize him. He was already disturbed from the guilt of having “abandoned” Jimmy by divorcing Gloria, and he was worried over the safety of his second marriage. Even after a year of being married to Evy, he was not sure he completely trusted her or could completely trust anyone again.

“My love for Jimmy kept a terrible thing from happening then,” Darren says. “But it was hard. so hard. I had only expected to be gone three months, not ten. When I came back, Jimmy didn’t remember me. ‘You’re not my daddy,’ he said.

“That was the worst thing that could have happened to me. I had Christian, and I suppose I could have tried to make Christian enough, but I could never have lived with myself if I had neglected my son. I had no right to bring him into the world and then neglect him because I wasn’t living in the same house. It would be like saying to Christian, ‘Look, you’re my son now, but you won’t be if I ever divorce your mother.’ ”

Week after vveek Darren drove his black Porsche to his ex-wife’s house.

“I’ve come to take you out, Jimmy.”

“I don’t want to go with you.”

“Please come, Jimmy. We’ll have fun.”

“No. I don’t want to go with you.”

Week after week he raced the Porsche away from the house in rage and frustration, dissipating the rage with reckless speed. Then he returned home to Evy and to Christian and to all the adjustments an angry man and a stubborn woman must make during the first years of marriage.

Evy felt sorry for him those long months when he returned wounded after visiting his son. But she was also “young and selfish and stupid and afraid of competition from Jimmy’s work and his first marriage and his first son.” When his depression turned first to sulkiness and then to anger. her compassion also turned to anger. And the evenings ended in bitter quarrels.

One week. sensing something different in his son. “You’re going to come with me, Jimmy,” Darren finally said. “I took the whole day off to see you, and I’m not going to waste it.”

Without protest, the boy moved towards the car.

That first triumph was just the middle of the struggle. Jimmy went—but only because he was bribed with toys, with ice cream. with Disneyland and amusement parks. And his first question was always. “What are you going to buy me today?” It was a long time more before the final answer to that question could be:

“I’m not going to buy you anything.”

“Okay, Daddy.”

With Darren’s acceptance by his son came a confidence that he had never felt before, a confidence in himself as a father and a person. He had the confidence to start doing something about a marriage that had had what Evy calls “a terrible terrible first year. Before we were married, everything was fun. We drove and laughed and quarreled and made up ten minutes later. Then, suddenly, we had to ad just to marriage and to each other and to a baby, and it wasn’t fun any more.”

“People are really not made to be living together,” says Darren. “They’re too different. In a happy marriage, you just finally learn to live with the other person’s faults.”

“We have a happy marriage now,” Evy adds. She characterizes her husband as “beautiful. good. extremely affectionate— and bad. But the badness is only because of his temper. Basically he’s very nice, and I love him. But we’ll always have conflicts because you can’t change anyone else. You can only change yourself. The greatest, happiest marriage I know of is the marriage of Veronique and Gregory Peck. But we can’t imitate them because the things Veronique does for Greg are things Jimmy would never allow me to do. When Greg’s working, she goes to the set and sits there all day, and he talks over everything with her. Jimmy would hate to have me on the set. So we’ve had to find a different pattern for our life.”

The pattern they have chosen owes more to the middle class New Jersey world in which Darren grew up than it owes to Hollywood. It may change if Darren’s new seven-picture contract with Universal-International pushes him over the hump to real stardom. But, as of now, they live in a relatively small house in one of the canyons. They have only owned the house for a year, but Darren is already restless to buy a new house, one with “at least an acre of land for the children to run on. Children need a place to run and run and run.” Evy drives Christian to nursery school three mornings a week. She has no maid. Although she was under contract to a studio herself before her marriage, she will not return to acting.

Darren’s oldest son stays with them every weekend, and the two boys share a room with the baby. At the fairly frequent parties the Darrens give, the women sit in the living room and talk while the men play pool in a downstairs den that Darren and his father built from the garage. Darren is amazingly good at building and fixing things, and he finds a special satisfaction in working with his hands.

His aim in life is to be really successful in his profession and “to raise children who are healthy mentally and physically.” He believes in disciplined, orderly children. He believes also that a father “should not be buddy-buddy with his children. They don’t want it and they don’t need it. They need him to be a father, not a friend.”

He has a strong relationship with his own father and he will never change his name legally. “Only two boys—my brother, John, and I—carry the name of Ercolani. It’s a good Italian name and I like it. It belongs to me, and I want to hand it on to my three sons.”

For a moment he seems startled by what he has just said. Then he smiles—an easy, broad, relaxed as a kitten with a stomach full of warm milk smile—and repeats—with pleasure, pride, and confidence—“to my three sons.”

—By ALJEAN HARMETZ

See Jimmy in “For Those Who Think Young,” UA, and “The Lively Set,” U-I.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1964