“The Difference Is You”

You know how the song goes:

“What a difference a day makes, Twenty-four little hours. . .”

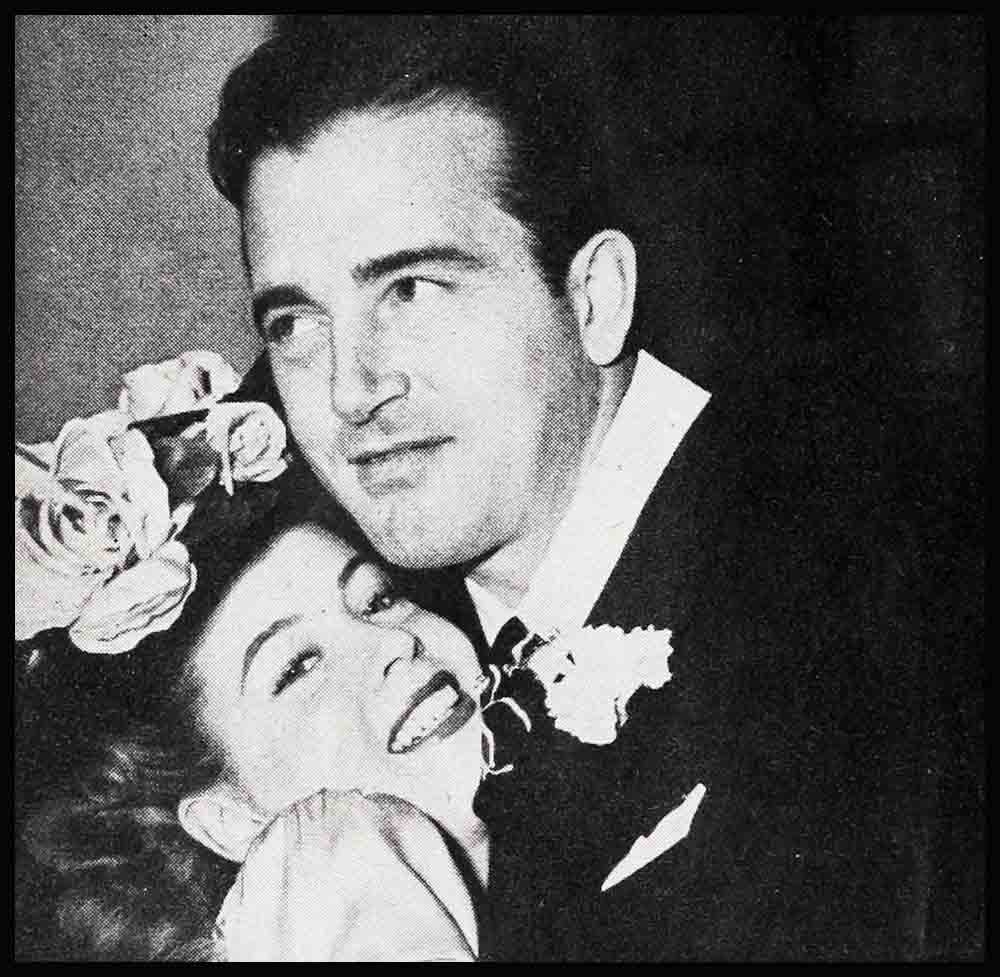

On New Year’s Eve, standing in a silent little desert Street in picturesque Palm Springs, California, trying to prop up their sleepy eyes for one more minute, to watch the waning desert moon and be sure it was authentically, truly 1945, Gloria De Haven and John Payne softly sang that tune to one another.

For they knew when their miracle day had happened. That was September 23, 1944. The difference it made was that, where before they had been like so many young folk today, just two lonely people, only a little more than three months after it, on December 28, 1944, at the Beverly Vista Community Church in Beverly Hills, they became one.

Love did it, of course. Love, that is, using such assistants as Sue Carol Ladd and a blind date and a set of ideals. Love whipped it all up into a wartime romance built on serious wartime emotions but given the sparkle of a Christmas ending.

AUDIO BOOK

It began, as all truly romantic stories do, most accidentally. Alan and Susie Ladd were giving a party and they wanted Gloria and Johnny to be among those present. Knowing neither of them had any permanent date, Sue and Alan thought it would be nice if they came together, so Susie, as hostess, rang up John and asked him if he would bring Miss De Haven, even if he had never met her.

As fast as you can say “yes,” John, who felt no agony when he recalled the photographs he’d seen of Gloria, said that would be dandy. Sue then called Gloria and Miss De Haven, visualizing the Payne height, profile and shoulders she’d watched on the screen, demurely replied she’d be delighted.

Thus was set up the least blind blind date in history.

Came Saturday night and Miss Pocket Venus had on her favorite black chiffon dress, a neatly concealing, nicely revealing number, but she didn’t have on her coat, not wanting to look too eager. Besides, she wasn’t absolutely sure she was being called for.

But suddenly a knock sounded on the door. A voice called, “Payne’s here.” Miss De Haven opened the door, introduced the mass of rugged male grandeur she saw there to her mother, put on her coat and let said male grandeur escort her down to his car.

They drove to the Ladds and they made polite, very stilted conversation all the way and their hearts went right on beating perfectly normally. For, you see, they were both accustomed to beautiful people of the opposite sex and because they both were lonely and romantic, they wanted a. lot more than beauty—a lot more.

The Ladd party turned out to be a gay and giddy affair and, as at all such gay gatherings, there were some guests who got so high they climbed right up into the stratosphere. But not Mr. Payne and Miss De Haven. Gloria doesn’t drink at all, so she sat quietly and prettily by John’s side at one of the tables out under the trees, and John, being a gentleman and her escort, didn’t go barging around and leaving her. Presently they departed, quite early. As they drove past Ciro’s, they commented that a new show was opening there the following Wednesday.

“Would you like to go?” asked John.

“Yes, I would,” said Gloria.

“I’ll call for you Wednesday at eight.”

Now Gloria didn’t know that this Ciro’s date was a test, but it was. To Johnny, out of the Army for only three weeks, deepened by the contact with the men he had met in the camps, all values were serious. In fact, seriousness had been a keynote of his life.

Like most old Virginia families the Paynes had had very little money and very great ideals. John was well brought up but there was never a moment’s doubt that he would have to earn his living, every inch of the way, and until he finally got into pictures he went through some lean times.

In Hollywood he married Anne Shirley, as every one knows, and about three years ago they were divorced, as everyone also knows, for reasons that no one knows. When he and Anne now meet, they behave like well-bred people, and they share the custody of their small daughter, Julie, six months a year apiece. After their divorce he made a try at several gay friendships but they were never any more than just that.

Then John entered the Air Corps. He was terribly earnest about becoming a good pilot and he spent his own money and whatever time he had left over from his Army training to purchase outside flying lessons. He saw the boys around him being pushed around by the girls they had left behind and the subject of how to find a true love became almost an obsession with him. Then on September first, along with 5,000 others in his same classification, he was let out of service. The Army considered these men too old for pilots (John will soon be thirty-three) and too big for bombardiers (John stands six feet four and weighs two hundred pounds).

I ran into him his first day back. Johnny said, that day, his eyes bewildered, “What’s the matter with me? I know pictures are important to morale. But do the people in them still have to be fussing about who’s got the biggest printing on the cast cards? Do they have to get themselves into an absolute lather because they haven’t got cream in their coffee? Look, I don’t want to be critical, but. . . .”

We changed the subject.

“It’s a strange thing,” Johnny said, “but in service the thought of death always lies there, unacknowledged, at the back of your mind. That makes you think about the things in life that are most important. I’m probably all wet, but I began thinking that the most important things are kindness; that is, tenderness, and loyalty; sticking to something, you know, sticking to ideals.” His face got abashed but he looked at me very straight from those deep, dark eyes of his and said: “I want to get married. I don’t know who the girl is, or where, but I want a wife.” He paused and then said, very low, “A man without a wife is only half a man.”

Well, that was the first week in September and he met Gloria two weeks later, and in the meantime he bought a house in Brentwood and furnished every bit of it by himself. You’d see him lumbering around, like an embarrassed mountain, in cretonne and drapery departments, and poking around in antique shops looking for lamps and chairs, but finally he got it all assembled and he moved in Julie, his four-year-old, for her six months with him. He began telling Julie she’d be with him till after Santa Claus came and he began teaching her new prayers and as he ruefully admitted, “I succeeded in getting Santa Claus and God awfully mixed up in her mind.” He was very determined to be a good father.

Which gets us back, in a somewhat roundabout way, to that opening night at Ciro’s. Gloria looked lovely, again in black because that was—but is no longer—her favorite color. She danced delightfully and John found what he had observed at the Ladds was true: She honestly did not drink. When they left the night club, Johnny said, “Would you like to come back here next Sunday evening, or would you consider spending a day at the beach, just fooling around in the sun?”

Gloria said, “Well, I’d like to do whatever you want to do most, but honestly, I’d prefer the beach. You know. I love dancing but night clubs seem so silly and right now they are so expensive it seems wrong in wartime, and I love being out-of-doors, maybe because I don’t get much chance at it, and. . . .”

Right at that moment Cupid let go that first arrow right smack through the Payne heart, because those were exactly the words John wanted Gloria to say.

So they went to the beach, and Gloria was even more Varga-ish in a bathing suit, and they stretched out on the sand and ate hot dogs and drank cokes and talked and talked and made a date to go to the movies the next night.

They went to the movies for six nights straight and then it was Sunday again, so they started all over. They talked about the technique of acting, and the timing on careers. Then they talked about the technique of living and the timing on that. Johnny got acquainted with Gloria’s frail and gentle mother and Gloria got acquainted with Julie. Johnny watched her like a hawk and he saw that it wasn’t any act: She obviously adored kids.

He said, later, very carefully, as he escorted her up to her front door, “If you married, would you want children?”

“Oh, a bunch of them—four at least.” He said, even more carefully, “But that might interfere with your career.”

She looked at him, in a kind of exasperation. “Oh, Johnny, as if I’d care! Why, I’d give it up in a minute for children.” And then she was blushing madly, and zing, went Cupid’s final arrow through the Payne heart and Johnny had his arms around Gloria and was saying, “Don’t let’s wait one minute longer than the earliest date we know we’ll have two weeks off for a honeymoon,” and Gloria was murmuring, “Yes, Johnny, yes, Johnny, yes, Johnny!”

John called his mother long distance that night in the old Payne household in Roanoke, Virginia. Her comment was, “Well, son, I know if you feel this way about her, she must be a wonderful girl.”

Almost that same moment, Mrs. De Haven, talking to a close friend said, “If you knew how I’ve worried that Gloria might not find the right man when she fell in love! She was always the best child because you could make her do anything by merely telling her that it would make you happy. Gloria could never give any man a part of her heart. With her, I’ve always known, it had to be all or nothing.”

A few nights later, Johnny and Gloria came to my house for dinner. Johnny came first, because Gloria had to work late, and he was going to have a quick bite of the hors d’oeuvres before he went over to the studio to pick her up. At least that’s what he said, but I soon came to believe he’d come alone so he’d get a chance to talk about her before the rest of the party arrived. Anyway, he dragged me into a corner and demanded: “You did say that you thought Gloria the nicest kid in the whole younger crowd, didn’t you?”

“I not only said it but believe it. Now you answer one. What’s the thing you love most about her?”

He eyed me gravely. “Her guts,” he said. “She’s so little and so young but what is so wonderful is how she accepts responsibility. She and her mother went through a pretty thin time of it when she was a kid, but Gloria carried that load on those little shoulders of hers, and did it in style too. She looks so fluffy, and that’s something I like, but actually that beautiful small head is set very firmly on her shoulders. She’s seen so much of glamour she can’t be fooled by it and she’s watched success followed so quickly by failure that she can’t be deceived by that, either. When she signed her first M-G-M contract, she was a minor and the judge instructed that one third of her earnings be put in War Bonds. Do you know she put one half of it in Bonds and lived on the balance?”

“In other words, she’s perfect.”

John grinned. “Absolutely.”

Later that evening I got hold of Gloria.

“Tell me what you like about John.”

She gave an ecstatic sigh. “He’s perfect.”

I let it go at that.

As it eventually turned out, both their studio production schedules double-crossed them. They expected two free weeks after New Year’s. Then they were suddenly notified they’d get four free days starting December 28.

Gloria bought herself a powder blue satin Street dress to be married in, because now powder blue is her favorite color. You want to know why? Powder blue is Johnny’s favorite color, and Gloria got the Street dress because she thought it was practical and she wore a hat, which she seldom does, because John likes hats. They had a very small wedding, only those closest to them—Gloria’s parents, her maid of honor, who was her sister Marjorie, and Johnny’s best man, Walter Lang, the director, and his wife, the vivid and charming Fieldsie, who used to be Carole Lombard’s secretary, Watson Webb, a society boy, who is also a film cutter, George Jessel, Johnny’s producer for “The Dolly Sisters” and the George Murphys, but when the service was over, they both played fair with their public and gave up half an hour of their precious four days to posing for the photographers, waiting outside the church and talking to reporters.

Hollywood honestly believes it’s got something in this romance.

And you remember how the song ends:

“That’s the difference a day makes,

And the difference is you.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1945

AUDIO BOOK