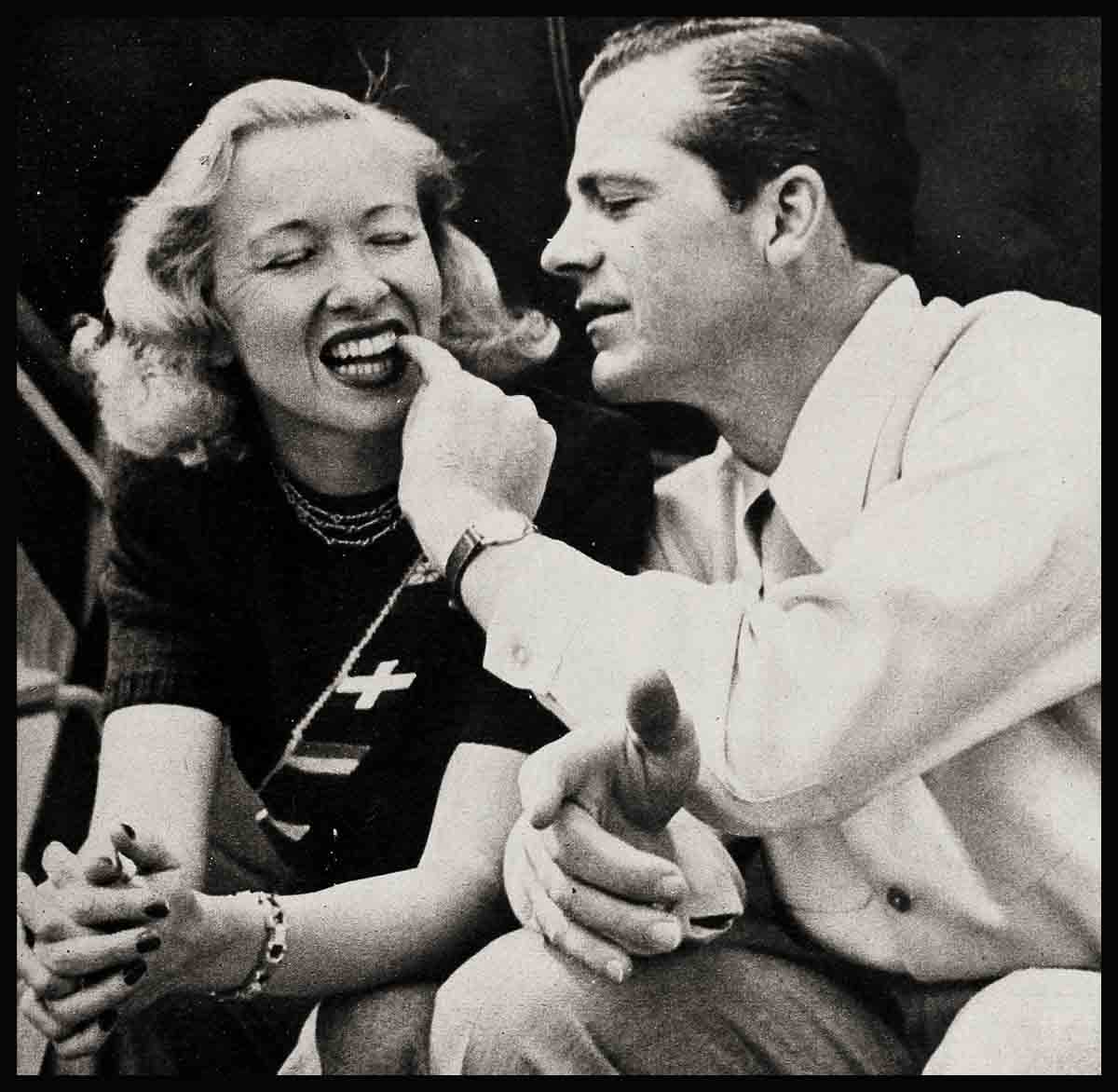

Dana Andrews: Problem Father

When Dana Andrews was in his young and hopeful twenties he went to college and studied child psychology. Thus armed with knowledge he faced the world bravely, certain that if he should ever become a father he’d know exactly what to do.

It was not long after the birth of his first child, David, that Dana realized there’s very little you can learn about children from books. In the first place, the books said that a father and his son should be pals. Dana was willing, even anxious, but every time he flexed his muscles for a little roughhouse with David, David eyed him as if he were crazy.

As David grew, so did his supply of baseball bats and gloves, fishing rods and basketballs. But none of this interested him. He cared only for music—all kinds.

When David got to be about four years old, Dana began to fear he’d have an introvert on his hands. But that was before a certain Sunday School program when David, who was not scheduled to perform, strode onto the stage and sat down at the piano.

“I will now play ‘High and Low,’ ” he announced in his baby tenor. Then he struck three high keys followed by three low keys, made a bow and walked into the wings.

While Dana sat flabbergasted, a small girl with a violin took her place on the stage. No sooner had she drawn her bow over the strings than David was heard to inquire in a loud voice, “How do you play that thing?”

In much haste and in mild confusion Dana rushed backstage to retrieve his son.

Dana’s next child was Kathy. Dana was delighted to have a daughter, for he himself had been overwhelmed by seven brothers. He prepared himself studiously for a personality like David’s, but Kathy evolved into a shy and self-conscious girl.

“Now what do we do about her?” he wondered.

Kathy went through her early years as though the weight of the world were on her shoulders. She studied hard, and was often on the honor roll. And if David weren’t David, he would have been shamed by her report cards.

“Why are you always at me to do my homework?” he asked Dana. “You’re always telling Kathy to stop studying. I don’t get it.”

“If you were more like Kathy—” Dana began, but he gave up.

However, now that she’s eight, Kathy has developed a delightful sense of humor. When Dana went to England to make a picture he took his entire clan along, and Kathy was captivated by the accent of the English children. Dana took her to see an Edgar Kennedy comedy one night. In this epic, Mr. Kennedy was having a hard time laying linoleum on his kitchen floor. After the linoleum had rolled back and whipped him in the breeches, Kathy leaned toward her father.

“My,” she said in clipped British tones, “isn’t he a mad fellow?”

Steven was number three in the Andrews family. He came along 11 years after David, and much to Dana’s chagrin is a born athlete. Watching a football game was fine, but after 12 hours’ work at the studio Dana wasn’t ready to kick a pigskin around the back yard.

“Why not, Daddy?” Steven wanted to know. “David told me you used to play with him.”

“That was a dozen years ago, Son,” Dana told him. “It’s something you wouldn’t understand. Now, how about a game of croquet?”

Steven was three years old when Susan was born and he didn’t take kindly to the idea of a new baby around the house. His limelight was shattered, and to focus attention on himself he reverted to baby talk.

“Why can’t one boy be like the other?” Dana wanted to know.

David had never talked baby talk. There was the time when he was not quite three and a strange woman had approached him on the street, cooing unintelligibly at him.

“You’ll have to speak more distinctly,” said David. “I can’t understand you.”

Now here was Steven at three, talking like a mere infant.

“He’ll get over it,” Mary said. “Just pay more attention to him and less to the baby.”

Dana took her advice, and concentrated on Steven to such an extent that he didn’t realize there was a hellion in the house. This was Susan, who hasn’t a shy or inhibited bone in her small body. David asks for things and accepts the answer one way or another; Kathy coaxes and weedles; Steven uses logic; but Susan—she just stands up and demands things. Dana’s reasoning goes over her head like a flying saucer, and in all probability she considers him the man who never, never says yes.

Even Kathy, who has taken over as a lead mare with the two younger children and repeats Dana’s lectures verbatim, is unable to convince Susan of the sanity of being deprived of something. And if Kathy can’t do it, no one can, for in the circle of her own family her self-consciousness disappears and she bosses the children like a construction foreman.

Their respective opinions of Dana are different, but they agree in one instance. They think he’s too stern. Dana says maybe he is, but his own father was a Baptist minister who brooked no shenanigans from his offspring. Dana feels that discipline never hurt a child.

Can I go out with the fellows tonight?”

David wants to know.

“Where are you going?” asks Dana.

“Oh—around.”

“No, you can’t go.”

“But gee whiz, Dad, why not?”

“Because I don’t want you floating around a city where you can get into all sorts of trouble. I want to know where you are.”

“But Dad, just because we go out at night doesn’t mean we’re a wolf pack!”

“Tell me where you’ll be, and you can go,” says Dana. And that is that.

Dana has been strict in the matter of allowances According to the books, this training is supposed to teach a child the value of a dollar. It taught David nothing. Be His interest runs to radios and recording a machines, anything with a motor, anything Dana says, that is expensive. David thinks nothing of requesting $200 from his father. He never gets it, but he doesn’t give up trying. When he had his heart set on a motor scooter, he had a proposition ready that he figured would melt Dana.

“I want the scooter,” he said, “so if you’ll throw in a little something, I’ll take a paper route to make up the rest.”

“What do you consider a ‘little something’?” asked Dana.

“Well, if you’ll throw in $100, I can make the other $50 within two months.”

“Very interesting,” said Dana. “You go right ahead with your paper route, and figure you’ll have the scooter in six months.”

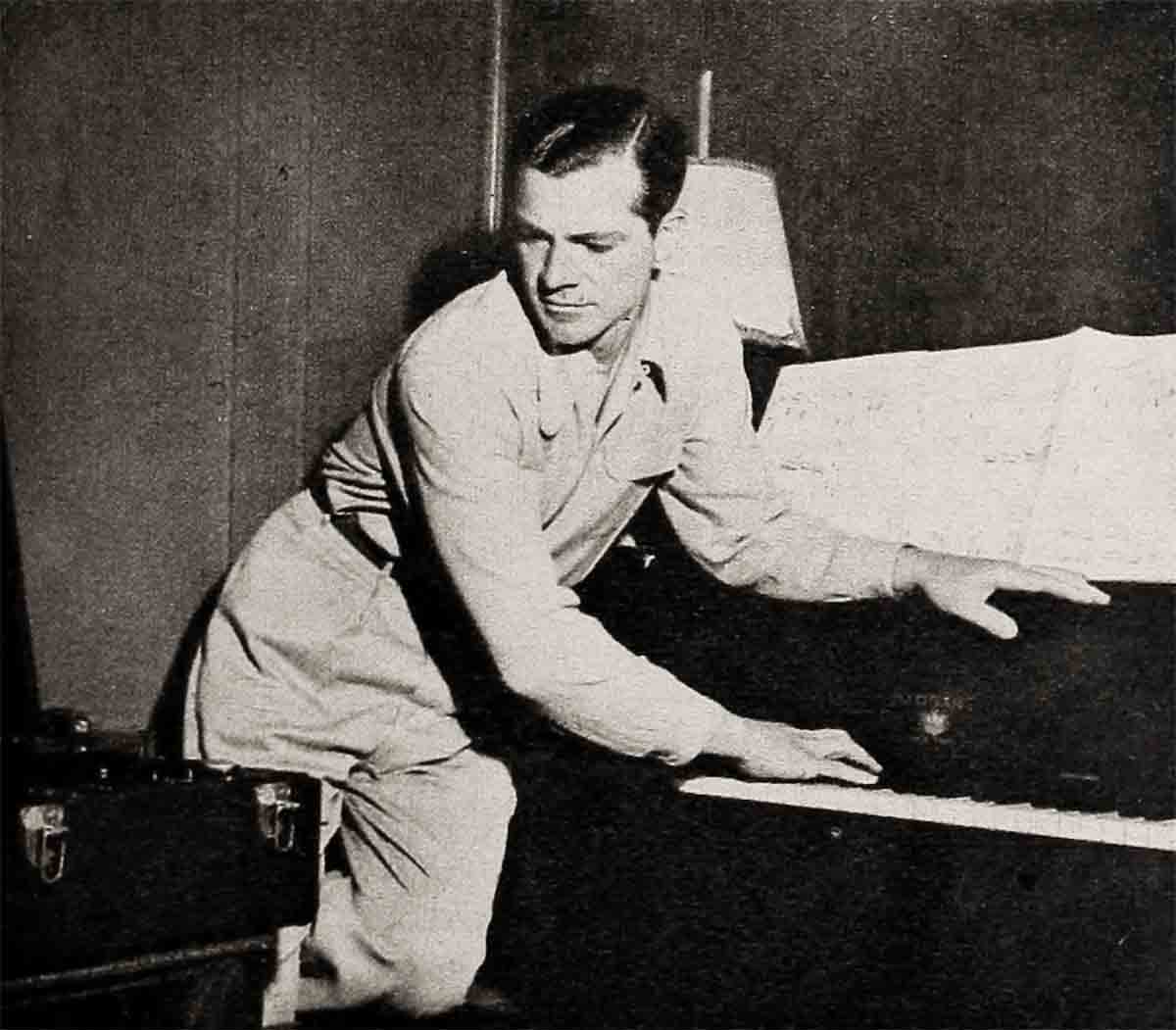

David’s latest yen is a pipe organ. Dana likes to encourage his love of music, but he feels that a few thousand dollars is an intensely unreasonable request. So even though David can play an organ, and play it well, he is confining his music at home to the piano.

Music is one thing that father and son have in common. Both like symphonic music, but David gets carried away by be-bop, too. “I don’t get it,” Dana says.

“You’re not hep, Dad. You’ve got to have wheels.”

“Wheels?” asks Dana, confounded.

And when David tunes in his short wave set and gets a dreamy sentimental tune, he says, “Boy, listen to that make-out music.”

“What,” says Dana, “is make-out music?”

“For make-out. You know—pitch woo—I guess you used to call it necking.”

There is something about children, Dana feels, that makes you wonder if you’re old before your time. There was the night he was amusing some of David’s schoolmates by telling them of his own experiences at school. They listened appreciatively for a while and then one of them piped up, “Gee, Mr. Andrews, how can you remember all that?”

David has been on the receiving end of long talks about the feminine half of the populace, but the advice didn’t sink in at first. Once he brought home a teen-ager about whom Dana still groans. “A real tomato,” he says in an unfatherly way. David didn’t appreciate his father’s criticism until this particular tomato relieved him of two months’ allowance in one short afternoon. Now he agrees that Dana’s advice about women is ‘pretty good.’ Nevertheless, Dana is happy that his son attends a boys’ school. “There are no girls available at Webb,” he says with great glee. And David throws him a dark look.

Steven and Susan are too busy vying with each other to pay any attention to the opposite sex, but Kathy’s interest is blithely fickle and frank. Every two weeks she comes home filled with admiration about a different boy at school. Her rapturous descriptions leave her two brothers openly disgusted.

The quartet has been made quite aware of proper social behavior—so acutely aware that Dana has decided not to show any of his movies at home any more. In the last movie he screened for the family, he made a rather definite pass at Susan Hayward. There was a sharp intake of breath from the three youngest, and Steven let go with a shocked, “Oh—Daddy!”

With the exception of David, they are all too young to realize that their father is a movie star, and Dana worries that it might affect them through the warped attitude of other children. So far, it hasn’t affected Steven, who told Dana recently that he considers him almost as good as Tim McCoy. And it certainly hasn’t affected David, who passes his days attired in a disreputable pair of levi trousers, a costume which irks the naturally neat Dana.

“What’s the matter with levis?” David demands. “All the guys wear them.”

“Do all the guys wear them so low that they look as though they’re going to fall off? And what about your hair? There’s a year’s growth there. They do have a barber at Webb, don’t they?”

When David sheds his levis, he usually makes a trip to Dana’s wardrobe closet, with the result that Dana never can find the exact slacks or tie he wants. Most of his favorite articles are in David’s locker at school.

Steven’s problem is that he goes at everything like a house afire, and then he slows down to an almost complete stop. In the morning he takes a flying leap out of bed, races to the shower, and then dawdles until he’s late for breakfast. The other morning he had just managed to get downstairs when the horn of the school bus sounded outside the house.

“But my waffle!” he moaned. “I want my waffle!”

“That’s just too bad,” said his father. “The next morning we have waffles, you’d better get dressed faster.”

That the foursome has spirit is undisputed. Take Dana at home after an average day at the studio. David wants to talk about a second-hand power boat he saw somewhere for a mere pittance, and the three youngest are clamoring at Dana’s feet for some romping.

“Not now, kids,” Dana says. “I’m too tired.” But after he’s taken a short nap and had dinner, they’re at him again.

Kathy goes for his shoulders, Susan latches on to his trouser legs, and Steven runs for the boxing gloves. Then they all start pleading for a camping trip, knowing that if they can once get him to promise, they’ll certainly go, for Dana never breaks his word to them.

When playtime is over, Dana points to the array of toys on the floor. “All right. Now everybody clean up his own mess.”

Kathy and Steven simultaneously point to small Susan. “She did it,” they chorus, and Dana delivers another lecture.

Dinner time is chaotic at the Andrews’ house. The only distinguishable conversation consists mostly of Dana’s voice booming out over the babble. “Quiet! QUIET!”

David came home the other day after six weeks at school and put in his first appearance before the family at the dinner table. On his upper lip was a rim of soft brown fuzz which was losing its battle to resemble a moustache. Dana took one look and was about to offer a suggestion about razors, but the three youngsters saved him the trouble. They greeted their big brother with hoots of derision. David shaved as soon as he’d finished his dessert.

After the kids were in bed, Dana put down his book and looked at Mary. “You know,” he said, “I think I’ll relax from now on. It’s beginning to dawn on me that they can all train each other.”

THE END

—BY JANE WILKIE

(Dana Andrews will soon be seen in 20th Century-Fox’s The Frog Men.—Ed.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1951

No Comments