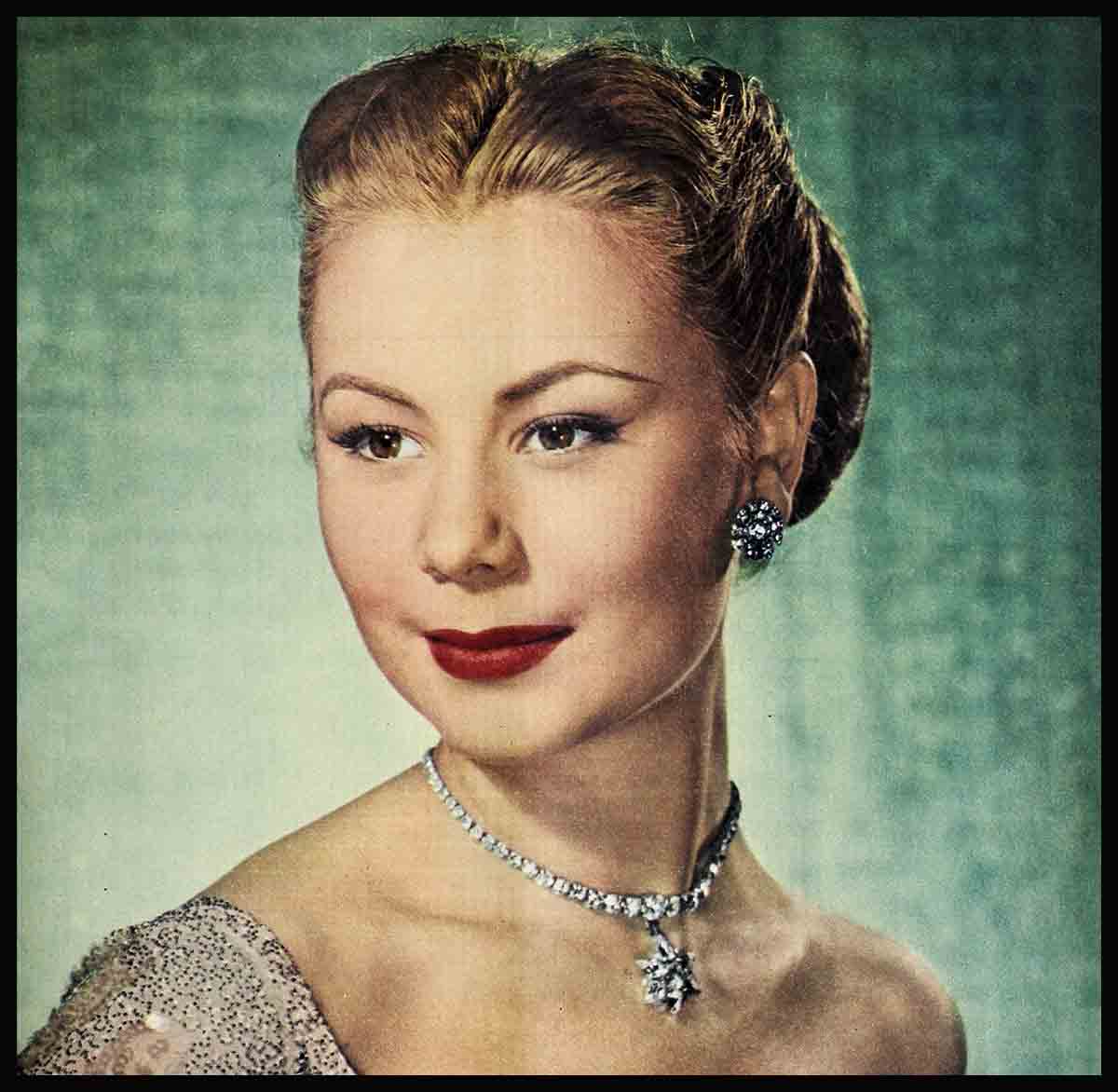

They Call Her Sparkle Plenty—Mitzi Gaynor

When Georgie Jessel isn’t making people laugh at banquets, or making people cry at funerals, he is busy searching for new talent for Twentieth Century-Fox.

“Georgie,” said Director Henry Koster, “there’s a singing-dancing girl named Mitzi Gerber in ‘The Great Waltz’ downtown at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Auditorium.”

That’s all Jessel needed to know. For months he had been hunting for a girl to play the bouncy, bubbling Lotta Crabtree, America’s first comedienne, in his production of “Golden Girl.”

Next day he reported to the inner circle luncheon group at the studio. “Two minutes after this Mitzi Gerber came on stage last night I knew I was” watching the greatest young personality in show business. Before the first act curtain I knew I had my Lotta. She dances like a dream, she sings like a lark. She made me laugh and cry. She sparkled like champagne. I’ll make you a wager, boys, she’ll be the next big star in Hollywood.”

Following a three-way test (singing, dancing and acting) Mitzi was signed to a long term contract with the understanding that after a warm-up in minor parts in “My Blue Heaven” (as the girl who made Betty Grable jealous of Dan Dailey), in “Take Care of My Little Girl’ (as the girl whose mother sent her to college so she’d stop smelling like a horse) and in “Down Among the Sheltering Palms” (as the torrid native dancer who attaches herself to William Lundigan), the studio would star her as Lotta Crabtree in “Golden Girl” and Eva Tanguay in “The I Don’t Care Girl,” Georgie Jessel productions. Studios have an unhappy habit of “making over” their embryonic stars, but all they did to Mitzi was change her last name to Gaynor—a name that made millions for them some twenty years ago. So far no one has confused her with the former Janet Gaynor, except a cab driver who picked her up one morning to take her to the studio. ‘“Miss Gaynor,” he said, “it’s a pleasure to drive you. I have been an admirer of yours ever since I saw you in ‘Seventh Heaven.’ ” Mitzi thanked him.

When Jessel told her that she was now on the Twentieth Century-Fox contract list, along with such names as Betty Grable, Anne Baxter, Jean Peters, Linda Darnell, Gene Tierney and Jeanne Crain, Mitzi, who is usually volatile and voluble, merely gave out with a limp, “Well, gosh, thanks.”

Mitzi, who since then has won Photoplay’s “Choose Your Star” poll, lives with her mother in a two-level, rented, furnished house in the Hollywood hills. She drives a black Mercury, wears red nail polish—red is her favorite color—collects ballerina dolls, eats everything in sight except parsnips, and sleeps in gaily flowered silk nightgowns. She saves motion picture magazines, and there are stacks of them all over the house. “I like to see how the stars live,” she says, “who their friends are, and what they are doing. I guess I’m star struck.”

She claims she is not superstitious, that it’s just that she doesn’t take chances. But if anyone whistles in her dressing room she makes them go outside, turn around three times, and spit before they come back in. If she drops a mirror she swears and spits to take off the curse. Her “77” in Polish. “Because,” she says, “it sounds so marvelously awful, and everyone looks so horrified.” She loves talking over the telephone, while balancing on one foot, and does arabesques during the conversation. Her mother says she even dances while she dresses. She never pulls her stockings up as other girls do. Instead, she gets the foot of the stocking on, then points her toes toward the ceiling, and pulls her stockings down. She puts on all her clothes, including her hat and gloves, and then steps into her dress.

Life with Mitzi can be dangerous, according to her mother. “As a dancer,” she explains, “Mitzi is constantly exercising her feet, so they’ll be exceptionally strong. I believe she can do everything with her feet she does with her hands except write. One of her favorite exercise tricks is to lift the coffee table, complete with china and knickknacks, from the floor with her toes. She’s been doing it since she was eleven, but she panics me every time.”

Mitzi and her mother are great pals. “I couldn’t exist without my mother,” she says. “She is right about everything.” Mitzi plays the piano by ear, and her mother writes poems for the magazines. Together they are composing a song called “Little Dingle,” inspired by the San Francisco cable cars. Mrs. Gerber is definitely not a movie mother. Very few people at the studio have ever met her.

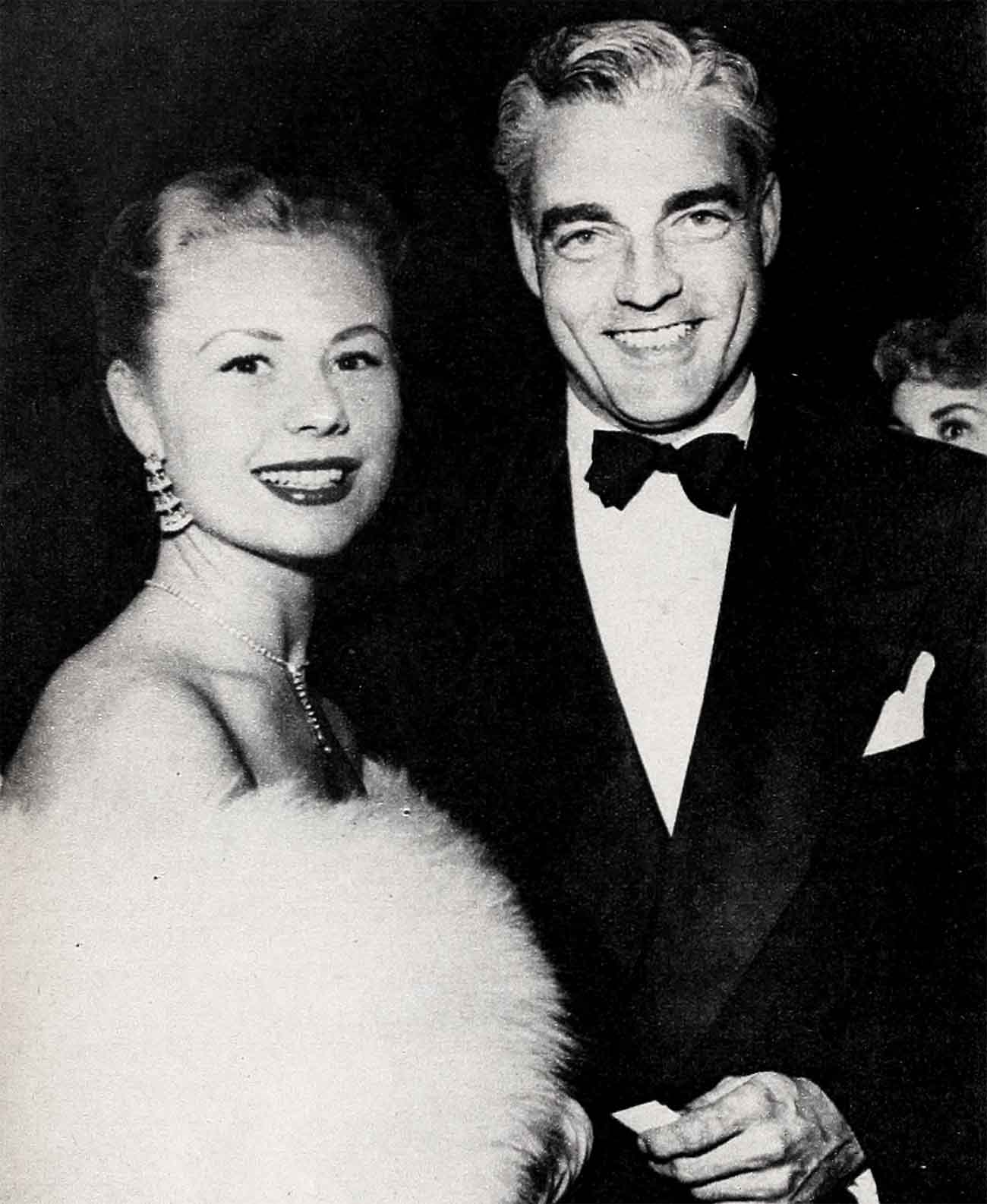

The biggest thrill in Mitzi’s life (even her exciting new career takes second billing) is her romance with Richard Coyle, who is an expert in negligence law and defense attorney for big corporations. Mitzi described him to a friend, “Oh, he’s okay, I guess, if you happen to like handsome, prematurely gray, brilliant, amusing, nice men.” She first met her “ideal man” when she was sixteen and playing in a Los Angeles production of “Naughty Marietta.”

Mitzi, Hungarian and impetuous, was all for leading Richard to the altar as quickly as she could get him there, but Mrs. Gerber, a very sensible mother, suggested that she wait until she’s twenty-one. “It isn’t that she doesn’t approve of Richard,” explains Mitzi, “on the contrary, she approves of him so much, and thinks he is such a fine person, that she wants him to have a wife who is grown up enough to make him a good wife.” And she adds, with the wisdom of the ages, “A girl can get away with things in her teens. People say, ‘She’s so young she doesn’t know better.’ But not in her twenties.”

Mitzi believes that if a girl has her eye on a man there is no point sitting at home staring hungrily at the telephone. She should do something about it, but in a subtle sort of way. “Look who’s talking,” says Mitzi with a laugh. “Now that I think about it maybe I wasn’t too subtle with my first crush. It was while I was in Junior High. He was the school’s leading athlete. I must have been an Annie Get Your Gun sort of character. Every time I saw him my mouth fell open. I was never late for classes that year for fear I’d miss a moment of his company. I even studied hard so I could show off in front of him. And I was always finding some excuse for strolling past the football field.

“I finally persuaded my girl friend to give could invite him to take me. And what happened—I had to go to a ballet class! Always, I had to go to a ballet class. That’s the horror of being a professional teenager. Months of maneuvering your man and boin-n-n-ng—classes. But I mustn’t feel too sorry for myself. There were other crushes. Several at the Powers Professional School. It’s part of being a teenager. Crushes for the teens—marriage for the twenties.

“I learned a lot from my first crush,” Mitzi continues. “I learned that boys at Junior High scare easily. They’re at that skittish age. So a girl should never be overanxious around them. There’s a fine line between anxious and overanxious. True, I strolled by that football field until my feet almost wore out—but at least I never popped up in the boys’ locker room and said to my dreamboat, ‘Why, fancy meeting you here.’

She usually has lots to say but when George Jessel told her she was a star Mitzi merely said, “Well, gosh, thanks!”

“Most of all I guess I learned: Never let a man know you are about to sink your claws in him.”

Women always have been aggressive, Mitzi thinks, but if they showed any signs of it in the old days they were immediately classified as “bad girls” by the overworked Mrs. Grundys. But ever since women left home and fireside, and especially the kitchen sink, thanks to modern gadgets, and went into business, manners have changed considerably. The male still wants to do the pursuing, and it’s his prerogative, but there’s no reason why, if he’s a mite dimwitted, or maybe just shy, he shouldn’t be given a gentle, but determined push.

“The best way to get to know a boy,” Mitzi advocates, “is to invite him to a party. As there will be quite a few other boys there he can’t suspect that you have ulterior motives. If you have on your prettiest dress, your highest heels and your flashiest smile, you’re in business, sister. Perhaps you can’t have a party at your home, then persuade one of your girl friends to give a chip-in party: every girl will bring a part of the refreshments and her own date.

“Also it could be that a good friend had to leave town suddenly and gave you two tickets to a football game, or to a popular play, and you were just wondering. . . . Naturally you bought those tickets yourself, but there’s no point in saying so. That just might be the little nudge he needs. Next week he’ll take you to the game—and it could become a habit. There’s nothing wrong in calling a boy if you have a good manufactured excuse. But be sure it’s good. Maybe you borrowed his handkerchief to get something out of your eye at a party, and of course you want to return it to him. The hostess gave you his phone number. Or maybe you discovered, just a block away from his office, that you have lost your change purse and haven’t even a dime for bus fare. He’ll loan you the change, and you’ll have to return it, etc., etc. It’s corny, but you can always run out of gas just a block or so from where your dream man lives. You appear at his door looking very helpless. It’s really the girl who does the choosing and the chasing; she always has, but don’t ever let the man know. You’re a dead duck if he suspects you. And don’t think, ever, that the worthwhile kind of man is easy to interest.”

In the land of the inflated ego Mitzi is probably our least conceited star since Baby LeRoy. But there was a time. . . . “I joined the ‘Song of Norway’ company in Philadelphia after a run with ‘Gypsy Lady’ in New York. I was a big mad professional and quite impressed with myself. But I was the newcomer in a very tightly knit group, who had all been together for three years on Broadway. To put it mildly, I wasn’t accepted immediately. Later we all became good friends. But it tock a little time. They taught me a valuable lesson.”

A gregarious young person, Mitzi is all for leaving that “alone” stuff to Garbo. Wherever you find Mitzi at the studio you find her knee deep in friends, who call her, incidentally, “Sparkle Plenty.” “Oh, I’m not saying that the ‘Song of Norway’ experience cured me completely,” she says. “I still have my moments of being pleased with myself. But somebody quickly comes along and cuts me down to the size of a postage stamp.”

On the set Mitzi is always bouncing, bubbling and clowning. “I’m the noisiest—person in the world,” she tells you, and proceeds to prove it. She’s a great one for calling people nicknames. Her nicknames, like her impersonations, are never unkind. She calls her leading men “Cousin,” often shortened to “Cuz.” Her two best girl friends on the lot, Jean Peters and Jeanne Crain, she calls “Pete” and “Dreamface.” Georgie Jessel she calls “Pappy.” One of her own nicknames is “Tootie.” Richard, however, is Richard. Never Dick, or Rickie, or anything but Richard. That’s a must. Mitzi is always hungry on the set, and between takes snatches nibbles from the workmen’s lunch boxes. Unable to be inactive more than a few moments at a time, she romps around the stage entertaining with imitations and puns. The imitations are wonderful. The puns are dreadful.

About the only way to make Mitzi lose her temper is to tell her that you hear that the studio is grooming her to take over Betty Grable’s pictures. It’s no secret that Betty, who has been on the screen almost twenty years, is far more interested now in her home, family and horses, than she is in her celluloid capers. But when a columnist wrote that Mitzi was a threat to the Grable throne, that young lady fairly blew her top. “That’s ridiculous,” she shouted. “No one can take Betty’s place. She’s in a class by herself.”

Mitzi is an only child (“Can’t you tell?” she asks) and was born in Chicago on September 4, 1931. Inasmuch as her father was a musical director and her mother a dancer, Mitzi took to ballet slippers like a duck to water. Before she was out of her teens she was a ballerina. But she is nothing like the traditional ballerina. She isn’t temperamental, violent, capricious or vain. Since the age of eight she has studied ballet, first with her aunt, Francine Woodbury, who showed her the basic ballet’ positions. She first studied seriously with Kathryn Etienne as her teacher, then later with Mia Slavenska, Anton Dolin and David Lichine. So when you see Mitzi dance, don’t think that’s just a little something she learned over the weekend. It’s the result of years of study.

When she was quite young her family took her to see Carmen Miranda in “The Streets of Paris.” That started her off on her impersonations. During World War II she entertained at USO shows with her impersonations of Carmen, Danny Kaye, and any celebrities who happened to amuse her. She was also featured comedienne-dancer of the special Air Force show which played all bases between Los Angeles and Charleston, South Carolina.

Mitzi attended Tilden and Chandler Grade Schools in Detroit, and later Le Conte Junior High School and Powers Professional School (which is run by Mala Powers’ mother) in Hollywood. While playing in a long run of an operetta in San Francisco she was tutored by a Mrs. Mack. Mrs. Mack recently came backstage to see her former pupil when Mitzi was in San Francisco making personal appearances with “Golden Girl.”

“Mitzi,” said Mrs. Mack, beaming with relief, “I despaired so of your arithmetic. But I won’t worry about it any more. After seeing you on the screen this afternoon I know now you’ll always be able to pay people to add and subtract for you.”

Mitzi made her debut with Edwin Lester’s Civic Light Opera Company at the age of fourteen (she said she was sixteen), in “Roberta,” and subsequently in “The Fortune Teller,” “Gypsy Lady,” “Song of Norway,” “Louisiana Purchase,” and “Naughty Marietta.” It was during this show that Lester saw her clowning during rehearsals and decided to produce “The Great Waltz” with the comedienne part especially written for Mitzi. Choreographer Aida Broadbent devised a comedy ballet which was the highlight of the show. And that’s where Jessel discovered her.

“I’m afraid,” says Mitzi apologetically, “that I make very dull copy. I’ve never had a single handicap in my life. My family has always encouraged me. I have never been shy. I have a wonderful mother. And on September fourth I’ll be twenty-one years old and I’ll marry the man I love.”

All that and stardom too. Couldn’t happen to a nicer girl.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1952