Man Of Conflict

One day not long ago I took a young lieutenant of the United States Army Air Corps out to the M-G-M studio for lunch. He was just back from his completed missions over Germany and he wanted to see a movie set in operation.

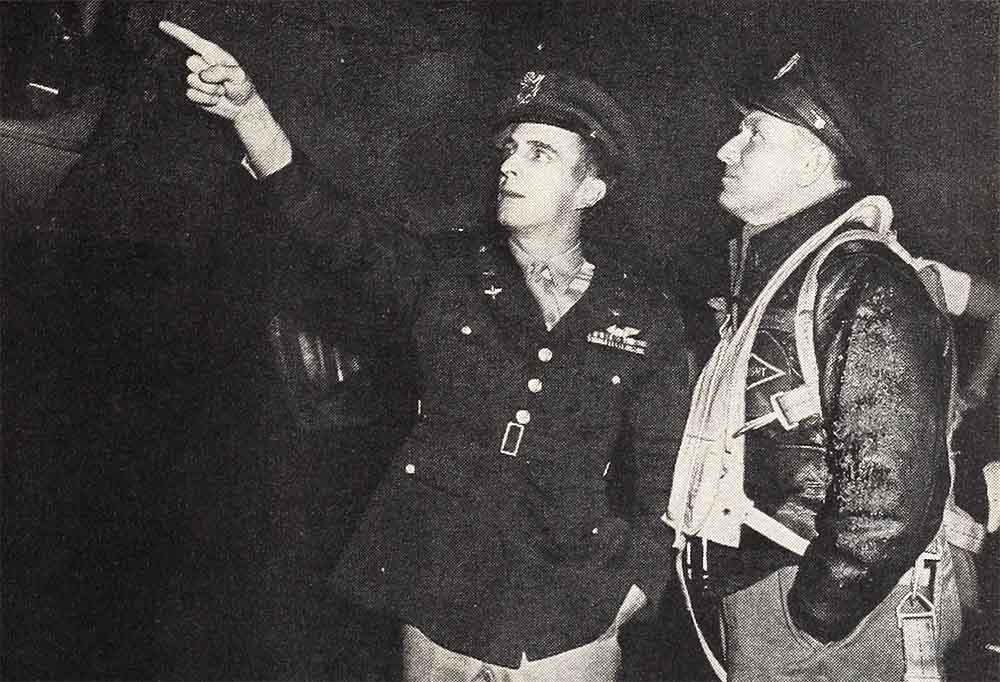

All of a sudden I noticed that he was staring over my shoulder with wide eyes and then in a low, awed voice, he said, “Look, there’s General Doolittle!”

I turned hastily and there, as you have doubtless guessed, sat Spencer Tracy minding his own business over a bowl of chicken noodle soup.

In all motion-picture history, I do not think there has ever been a man so identified with the parts he plays as Spencer Tracy—and I believe it has had an amazing effect upon his own life and his own character.

There is, for instance, a good deal of confusion in the public mind about Father Flanagan of Boys Town. I’ve often wondered if the good Father ever went anywhere and said he was Father Flanagan and had somebody answer, “Oh no, you’re not! I’ve seen Father Flanagan and you’re not him at all.” Because Spencer Tracy’s performance of him lives forever in the minds of those who saw it as the man himself.

AUDIO BOOK

All this is perhaps because, when you come right down to it, Tracy is the finest actor in motion pictures today. I told him that not long ago and he looked so terribly unhappy that I instantly took it back. But, as the kids say, the crack still goes.

Incidentally, Spence and I had a hard time getting together for a visit. Wednesday and Thursday evenings were out because the pilot who flew him on his recent tour of the camps in Hawaii was in town on leave and he and the whole crew were staying with Spence. Nothing, I soon discovered, was going to be any fun for them unless Spence was along and they summed up their verdict in one brief phrase, the service man’s accolade, “What a guy!” Politely, they all invited me to come along to dinner with them, but somehow I couldn’t go. Just by the way they spoke you knew that a great comradeship had grown up between these air men and Tracy, that they had all sorts of private reminiscences to share and it didn’t seem fair to interfere with their good time.

Then Friday night is Spence’s night with Johnny and Susie, his son and daughter. Nothing is ever allowed to happen to that. It’s their own special night, they always have plans made way ahead of time so that they get the double joy of anticipation and I can’t imagine anything that would persuade Spence to disappoint those two kids. He has so much imagination himself that he’d suffer more than they would.

Like the time Spence was waiting for Johnny to fly home from school. Johnny was about thirteen or fourteen then, I think, and he had always traveled by air. But the plane was several hours late and Spence waited and walked the floor, although he kept getting reports from operations that everything was okay—they’d been held up by weather—they were reporting in okay. Finally, they landed and Johnny was there all right and his father said, “You feel all right—get upset or anything?” And the boy looked at him and grinned and said, ‘I’m okay, Dad, but you certainly look funny, like you’d been wrung through a wringer.”

That’s Tracy, all right. In his imagination, he’d probably gone through a thousand dramatic things that could have happened to the son who has always been so close to him.

We had our visit finally.

You can’t always tell what people are going to look like to you after a period of years when you haven’t seen them often. If you see a friend every week or even once a year, you hardly notice the change at all; you do your growing or backsliding together. But it was four or five years since I’d talked to Spencer Tracy—and after the first sentence, I was aware of the spiritual and mental growth of the man.

And he does it the hard way! For all his humor and his easy comradeship and personal charm, Spencer does everything the hard way. He’s had more ups and downs inside himself than most people, he suffers more over his mistakes and gets more fun out of his victories than anybody I know.

That is one reason that the Damon and Pythias friendship between him and Clark Gable always fascinates me. Maybe that friendship, which is and should be one of Hollywood’s glories, stemmed from the friendships they played on the screen, in “Test Pilot” and “San Francisco,” among others, but their own friendship is closer than that. Yet no two men were ever more different in their thinking and their ways. Gable is—just Gable. Uncomphcated as a seeing-eye dog. Tracy is as complex and difficult a guy as you would ever want to meet.

You have to know that here is a super-sensitive, highly emotional, forceful man with all sorts of inner conflicts. A man of ideals beyond the power of most humans to fulfill, of great desire for things of the spirit and with correspondingly lusty enjoyment of all the good things of life. You can’t help but wonder what time and the things that have happened to him have done to him.

I thought about it all one night when I went to dine with Mr. and Mrs. Bud Lighton—Bud being the man who produced Tracy’s great picture, “Captains Courageous.” over our heads, as we sat after dinner in their charming living room, we could hear footsteps pacing back and forth. And Bud, with his wise smile, said, “Spence is thinking something through. He always has to think it through. Some people can let go of a thing before they know the answer, but not Spence.”

When I talked to Spencer Tracy, I knew that he had been having experiences and that they had made him grow—and growing isn’t always-fun.

The minute I mentioned “A Guy Named Joe”—I knew that was part of it. I knew that Joe had done something to him. Just as he did something to you and me. I had an idea that being a guy named Joe for all the people in America had brought Tracy that same humility.

I asked him if that was so and he said, “Yes. Of course.” With an embarrassed chuckle and a twinkle in his eyes, but there it was.

“You lived Joe, didn’t you?” I said.

But again he looked embarrassed. Almost shy. The role he dislikes most in life is that of being an actor—especially when you say he is a great actor. Because he has an almost brutal honesty about himself. He wanted to be an actor and so he became one. He has reached real heights on the screen that I do not believe anybody else has touched. But he isn’t an actor in the sense of knowing all the tricks, all the technique, all the ways of getting effects that most great actors have had.

For instance, when he was asked to play General Doolittle, he took a long time making up his mind. Had the studio concerned. They thought maybe it was because the part in “Thirty Seconds over Tokyo” was relatively small—wasn’t, as they well knew, nearly big enough for Spencer Tracy. Finally somebody went to see him. Spence actually didn’t know what the man was talking about! He just lowered his head and stared at the visitor and said, “I don’t know if I can do it right. I don’t know whether I can or should even attempt to—to show them what a man like Doolittle is and must be. It’s such a big thing to try to do I’m sort of scared of it.”

So when you tell him what a fine performance he has given, he wriggles and squirms under it. Gets red down the back of his neck. Starts to talk about Clark, or you, or what shows did you see before you left New York? He doesn’t like talking about himself much. Rather tell you about the ranch out in San Fernando Valley which Mrs. Tracy runs and where he spends his week ends, though when he’s working he holes in at the hotel. Rather brag about Clark’s war training film.

But I wasn’t having any. I had a question in my mind and I was going to get it answered.

In “A Guy Named Joe,” Spencer played a pilot who was killed but who found a hole in the sky and went on serving. Nobody in the picture ever mentioned immortality. It had plenty of belly-laughs, a great love story and some magnificent flying. But when it was over, you had a wonderful new inner feeling that you had seen immortality and that the men who have gone West in this war still carry on somewhere. I wanted to know whether these things had any lasting part in the forming of Spencer’s philosophy of life; whether becoming these people—who are different in so many ways—as he does in order to get them over to you and me, went inside him and contributed to whatever he was thinking about life in these days when everything is reaching and searching.

“Did you believe ‘A Guy Named Joe?’ ” I asked flatly.

“Yes—I believed it,” he said. “There was something about it that made sense. At least, the way I see it. I don’t suppose I ever thought much about it. immortality, I mean. But when—well, Joe was a guy and you got to know him pretty well and when he died and then went on doing a job, trying to serve, still working out his own problems and his own inner feelings—you thought, why sure, this is it, this is the way it will be. There are certain things you can take with you. Joe took a lot of them, good and bad. He had to go right on living and loving and learning and—you felt it kind of got through to him after a while that he was immortal. So the sooner he got on with finding out how to do it, the better. Oh sure, I believed it.”

All highly imaginative and emotional people suffer a lot about this war. When, like Tracy, you can become another person to play him on the screen, you are a cinch to become a lot of men and women you read about, to enter into them, to come closer to knowing how they feel than others do.

So—I asked Spence what he felt about this present time. I asked him if he’d gained anything from Father Flanagan and Doolittle—and even that simple, shining soul Manuel in “Captains Courageous”—that helped him.

“I guess I just have an idea that you can’t change the laws,” Tracy said slowly. “I guess I feel that—we planted this war all during the peace years. I don’t know whether I’ve evolved what you’d exactly call a—a working philosophy. But when you get to know and realize what kind of fine people there are in this world—like Father Flanagan—when you touch a man like that even in make-believe—then you know it had to come from somewhere. You know there couldn’t be things like these men see and do if—well, if it wasn’t all possible to every man.”

He hesitated quite a while and then said, very simply, “I have come to believe that every man has a possibility of choice within himself. And I believe that whatever there is—will make that choice come true if you yourself work with it. The choice isn’t just one crossroads. It’s almost a new crossroads every day. But you yourself are’ the one who can decide—and when you do, the road is open to you. If you take the right road, I sort of imagine you get help all along the way. And if you take the wrong one, you have to struggle back and find where you went wrong and that’s pretty unpleasant. I don’t believe you ever lack—well, guidance or direction—if you want it.”

Perhaps the big reason he makes these great people come so truly to life on the screen is because Tracy believes in them far more than he believes in himself.

I knew, as perhaps not many people did, that it was humility that kept Spence from going overseas to the men before he did.

“What can I do?” he said, miserably. “I’m no good. I’m just an actor. I have to have a part and a play and everything and how can you do that? I can’t talk well myself. I’m not the guy they see up there on the screen at all. I’m just a very ordinary man and probably not nearly as sure of things as they are. I can’t sing or dance or tell stories. Send somebody who can make ’em laugh, somebody who has something to offer.”

He told me the happiest moments he had ever had in his life were when in Hawaii he realized that the men did want to see him, to talk to him, that it did something for them to know someone they had admired and enjoyed on the screen had come out to visit with them. So that now he is looking for a play—or plays—that he can do in the camps—now he has some restored self-confidence. I actually think that he believed they would take one look at him and say, “Is that Spencer Tracy? What a sell. Tell him to go away and send Betty Grable.”

He’s a reasonably difficult and complex and complicated guy—this guy named Spencer Tracy. Hot tempered, bull-headed, violent and strong in anything and everything he feels, good or bad, right or wrong.

But I came away with a picture I think I shall always keep, one that I seemed to get with an inner sense, as though it was happening all the time while we just sat there in his pleasant chintz-hung living room. A picture of man, as man, always struggling upward.

Struggling. Oh yes—and sometimes against obstacles—sometimes pushing things out of the way—sometimes slipping and falling and going ahead on his hands and knees, sometimes moving with a great leap and a song of joy. Struggling all right. But always upward.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1945

AUDIO BOOK