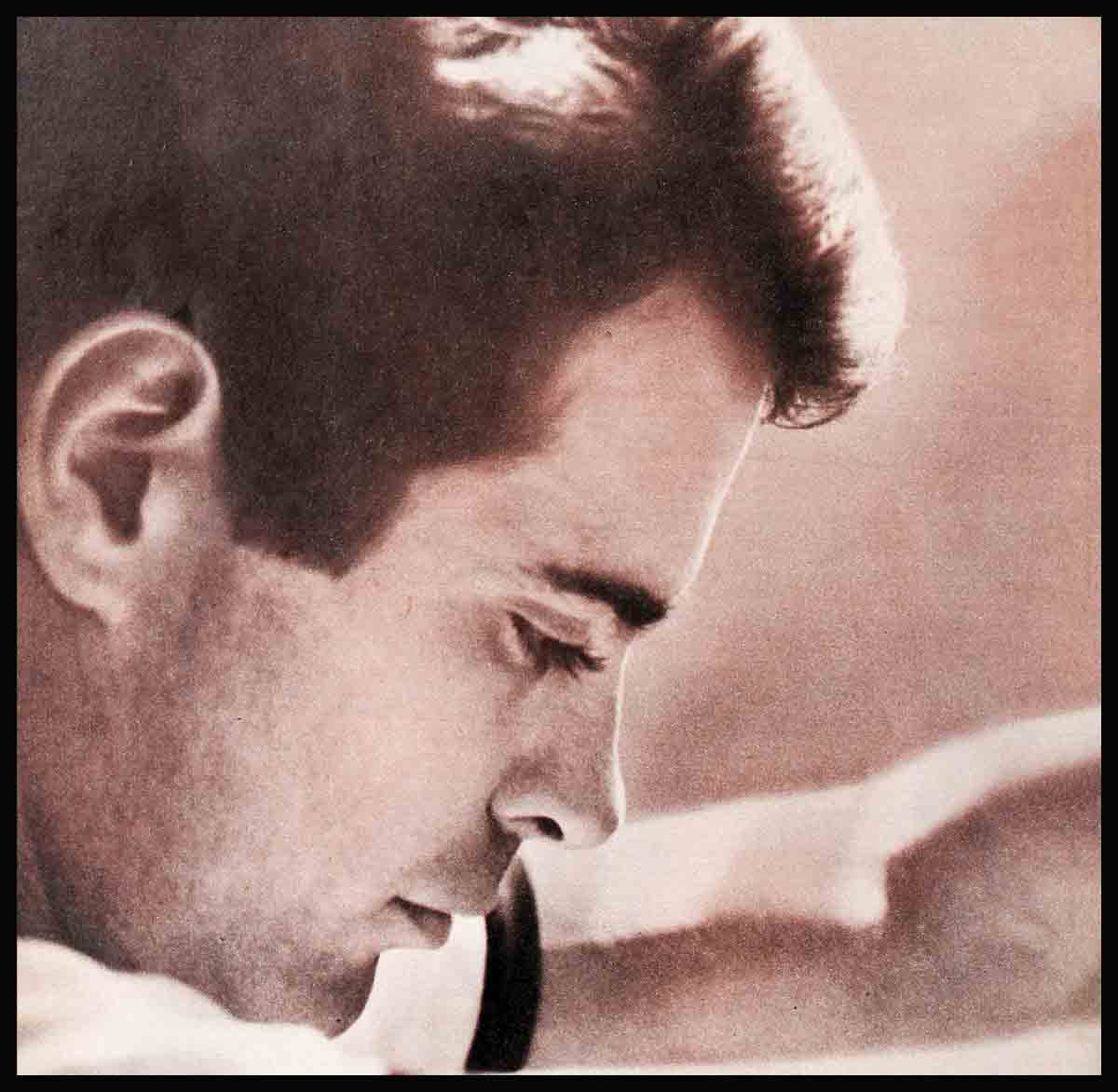

The Ordeal Of Gardner McKay

“The trial was hell,” Gardner McKay said softly. “A very quiet hell. I lost a lot of sleep over it. The thought of something I was ashamed of being known to the whole world sickened me. It was quite an ordeal.”

Gardner was twenty-eight years old when the ordeal came, but shame and pain have aged him far beyond those years. He wears his new maturity well, but the price he had to pay for it was unnaturally high.

Even after a jury of eleven women and one man delivered the verdict of “Not Guilty,” delivered the verdict that in their opinion he had not fathered eighteen-month-old Gabrielle Frantz, daughter of Mrs. Patrice Frantz, his ordeal was not over. There was still the agony of wondering what his family would think, his friends, his business associates. But most of all, what would Dolores Hawkins think? She and Gardner had been planning to marry—but when the trial came along, the marriage had been postponed.

Ever since he had been linked romantically with the New York model, he has been reluctant to talk about her. He was even more reluctant to do so now. When he finally did, it was with measured understatements, haltingly spoken in a barely audible voice.

“I told her before it broke,” he said almost painfully. “I wanted her to hear about the paternity suit from me, not from the papers. I knew what was going to happen. I told her the truth.

“I was terribly worried about the effect it would have on our relationship. But all I got from her was loyalty and more loyalty. She was in New York at the time. I’d call her frequently. But being three thousand miles apart made it hard. I had misgivings about how long her loyalty would stand up when she was faced with comments from all kinds of people—people at work, people she met socially, people who believe what they read and might try to make her believe it, too. I wondered how durable her faith could be in the wake of rumors. . . . I had faith in her, but I know the power of gossip. . . . I know it’s wiped out more people and more happy relationships. . . . I didn’t want that to happen to us.”

When the scandal first broke and the newspapers headlined the news that twenty-three-year-old cocktail waitress, Patrice Frantz, had named Gardner as the father of her child, he knew he had two plans of action. He could run like a thief, or he could stand up to the accusations like a man. Grimly, he decided his manhood was on trial just as much as the charge of fatherhood.

“From the very beginning,” he recalled, “I decided not to cringe. You know, there was an out of court settlement proposed. Boy, was that tempting! But I decided to beat the thing down—once and for all. I realized that I was going to be tried for the most distasteful type of thing I could imagine, but, even in the face of inevitable censure, I decided to stand on truth. I felt confident of the outcome. . . . I never thought I would be accused of something that wasn’t true. Some thought my philosophy naive, too hopeful, but I thought it was a good way to be.”

His confidence faltered

About the second day of the trial, his confidence began to falter. As he sat listening to the testimony against him, he was horrified with fear that Mrs. Frantz might somehow manage to convince the jury that she and Gardner had been ardent lovers for months, and that they’d been intimate up to and including the moment of pregnancy.

If Mrs. Frantz did convince the eleven women and one man that he was guilty, it would do more than certify him as the father of her child. It would certify him as a Grade A heel. It would say to the world that he was not man enough to own up to his own deeds; not man enough to dig into his pocket to give food to an innocent little child born of his seed; not man enough to give a child her right name—his name.

“As I heard the testimony, I could hardly keep from opening my mouth and yelling, ‘That’s not true. That’s not true!’ But then I finally had my turn on the stand the third day of the trial. Anyone in the court can tell you how I testified,” he smiled. “I think I was direct—and a little too loud.”

In his testimony, Gardner admitted that he had indeed been intimate with Mrs. Frantz, but only once—and that was too long ago for him to possibly be the child’s father. He also made the disconcerting admission that he had sent her three hundred dollars to defray the cost of the baby’s delivery in Michigan. He acknowledged having sent her eighty-five dollars more for her return fare to California. Nor did he deny he had assured Patrice, when she informed him that she was expecting a child, “I will stand by you, be your friend and help you when I can.”

He had sworn to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth—and he did. But now he wondered if his admitted offers of money and friendship might be misconstrued as tantamount to a confession of paternity.

He silently prayed that the jury would weigh the whole story—not just part of it. He prayed they would realize that he had acted out of generosity. Would that generosity now destroy his reputation?

He remembered feeling cold panic at the thought that the jurors might not note the fact that his help ended abruptly when Patrice asked him to contribute to the child’s support. Would they realize that it was one thing to help a lady in distress—but another to support a child that was not his?

“It was unfair,” he gritted. “I’ve never gone out with a married woman. (Ed. Note: Mrs. Frantz, now divorced, was married at the time she became pregnant.) When I discovered this woman was married, I never dated her again. Yet the term ‘adulterer’ kept popping up. I was furious.”

The rage was obviously a mask for fear—fear that his life and his movements might forever be restricted by a guilty verdict.

“The loss of freedom was terribly important to me, in addition to everything else. I always want to be able to feel that I can move around if I want to—maybe go back to school, sail around the world or open a studio in Florence—without any sense of obligations or remorse.”

High-priced misadventure

Gardner put no price on his freedom—but there was an estimated price tag of a fifth of a million dollars on his misadventure. The cost in dollars and cents was a meager measure of his ordeal. What bothered him more was the emotional cost. And an emotional payment would be extracted regardless of the trial outcome.

“It’s funny,” he said sadly, “financial questions can be answered—but human questions go far deeper. The thought of paying cold cash every month to someone for something is difficult, sure—but the thought of being compelled to support a person you’re told you’re related to is far more difficult, I think.”

And so he wondered, those endless days in court, about the jury, about the world outside. He wondered what irreparable damage had been done him. He realized his career could be in jeopardy—but that was—and always will be—the least of his worries.

“I never fear for my future,” he insisted. “And my career is linked to that. I never want my career to be bigger than I am, so I knew I couldn’t be deeply hurt if my career ended. The only thing about myself that worried me was what was happening to the McKay name.”

As the doubts lingered, he hoped for a sign, one thing that would restore his confidence that truth would win. And then it came—it came the day Patrice Frantz, her former husband Robert Frantz, little Gabrielle and Gardner were instructed to stand before the jury so their features might be compared. Gardner was convinced that this, more than anything else, was what led to his exoneration. “The resemblance of the light-haired, blue-eyed child to the woman’s former husband was major to me,” he said.

Then, on Monday, the fifth day of the trial, the lawyers and the judge instructed the jury. “This took until around three o’clock,” he said. “When they were finished and the jury was sent out to reach a verdict, a pal and I took off for the docks at Venice. We walked around, killing time, while the jury deliberated. I knew the judge would probably dismiss the court around four-thirty in the afternoon and according to everyone, an hour and a half wasn’t enough time for the jury to reach a verdict.

“We’d walked further than we thought we had, so we had to run to get back to the court on time. It was a hot day, so I’d taken off my jacket. I’d just gotten my jacket on outside the courtroom door and as I entered, I was buttoning it. I’d expected to sit down and hear the judge dismiss the court with instructions to return the next day to continue deliberations. But instead, he called in the jury. As they entered, a couple of them were smiling. I tried to read their faces. I didn’t dare speculate on the meaning of their smiles.

“My heart pounded. . . .”

“And then the judge asked the forewoman if the jury had reached a verdict,” he continued, reliving the incident moment by terrifying moment. “She said they had. My heart pounded and pounded—I was sure everyone in the room could hear it. I sat motionless as the most important words of my life passed from the forewoman to judge to clerk. The clerk read the verdict and seemed to hesitate a bit before I heard him say ‘We find Gardner McKay not to be the father of . . .’

“I got up and walked out of the courtroom,” he said. “I didn’t say a word. I was just determined to get out of that place as fast as I could. People were smiling, milling around, touching me, saying things—but I kept walking. I got into my car and did a drag start out of that parking lot as fast as any start I’ve ever made.

“Driving home I felt numbly elated. One burden was gone but there were plenty of other currents still turned on. I thought about that little child and her life ahead. I didn’t want to see her hurt . . . but there was nothing I could do. And I thought about Dolores . . .

“The first thing I did when I got home was to place a call to her in New York. Then I thought I’d celebrate by taking a bath. The call got through to her while I was in the tub. I told her the news; she was delighted . . . delighted . . . All my conversations with her had meant a great deal to me. They’d kept me going. They helped me maintain my perspective. She had loyalty . . . great loyalty . . .

“Later on, a group of friends dropped by for a drink. One of them even brought along a huge, cooked roast. We had dinner and wine and then we all sat around and watched ‘Adventures in Paradise.’ ” he laughed. “I felt wonderful . . .

“My friends were great throughout the whole mess. I have the same friends now I had before. The studio was great about it, too. The head of our television publicity department would come to court—so did a member of the legal staff. The studio didn’t back me, but they were in back of me. No balloons went up at 20th when I won, and I’m sure they wouldn’t have gone into mourning if I’d lost. There’s a sort of sophisticated, quiet attitude running through 20th which I find very mature and pleasant.”

The only people whom Gardner felt did not give him a fair shake was the press. He does not think his exoneration received as much attention in the newspapers as the charge that originally catapulted him onto the front page.

“The publicity on the trial was slight, as far as I know,” he said bluntly. “They might have put it on the front page in Butte, but if they did, I never knew it. There was only a mumble on page twenty of the Los Angeles Examiner—nothing anywhere else. It might have been nice if the verdict had received as much space as the charge.” It hurt him to be accused so widely and exonerated to a few.

Almost providentially, the schedule of “Adventures in Paradise” whisked Gardner out of Hollywood a few days after the trial ended. He was sent to Tahiti for two weeks of background shooting. The trip gave him a chance to relax, forget and return to normalcy. During those two weeks he wrote to Dolores—bright happy notes—but all the while, he wondered in his heart what would happen to their relationship. He’d been dragged through the mud; had some of it rubbed off on her?

The best surprise

He brooded about it for those two weeks. He brooded about it till the day he flew back to Hollywood and stepped off the plane at Los Angeles’ International Airport. Then and only then did he get the verdict that really made him a free man.

As he walked from the plane, he thought he saw a familiar silhouette coming toward him. He stopped and looked again. And then in a moment he was looking at the one person in the world he wanted to see, but the last person he had expected to see. He was looking at Dolores. She had flown from New York to surprise him—to let him know that she was still loyal. It was the world’s best surprise.

Hand in hand they walked to a waiting car. And suddenly, that terrible, gnawing fear that had been inside him for months disappeared. At long last Gardner McKay’s ordeal—an ordeal that he would not soon forget—was over.

THE END

—BY WILLIAM TUSHER

Be sure to see Gardner in ABC-TV’s “Adventures in Paradise,” 9:30-10:30 P.M. EDT. Beginning October 1, the show will be seen on Sunday nights, 10-11, EDT.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1961

zoritoler imol

1 Ağustos 2023Simply wanna remark on few general things, The website design and style is perfect, the content material is really wonderful. “Taxation WITH representation ain’t so hot either.” by Gerald Barzan.