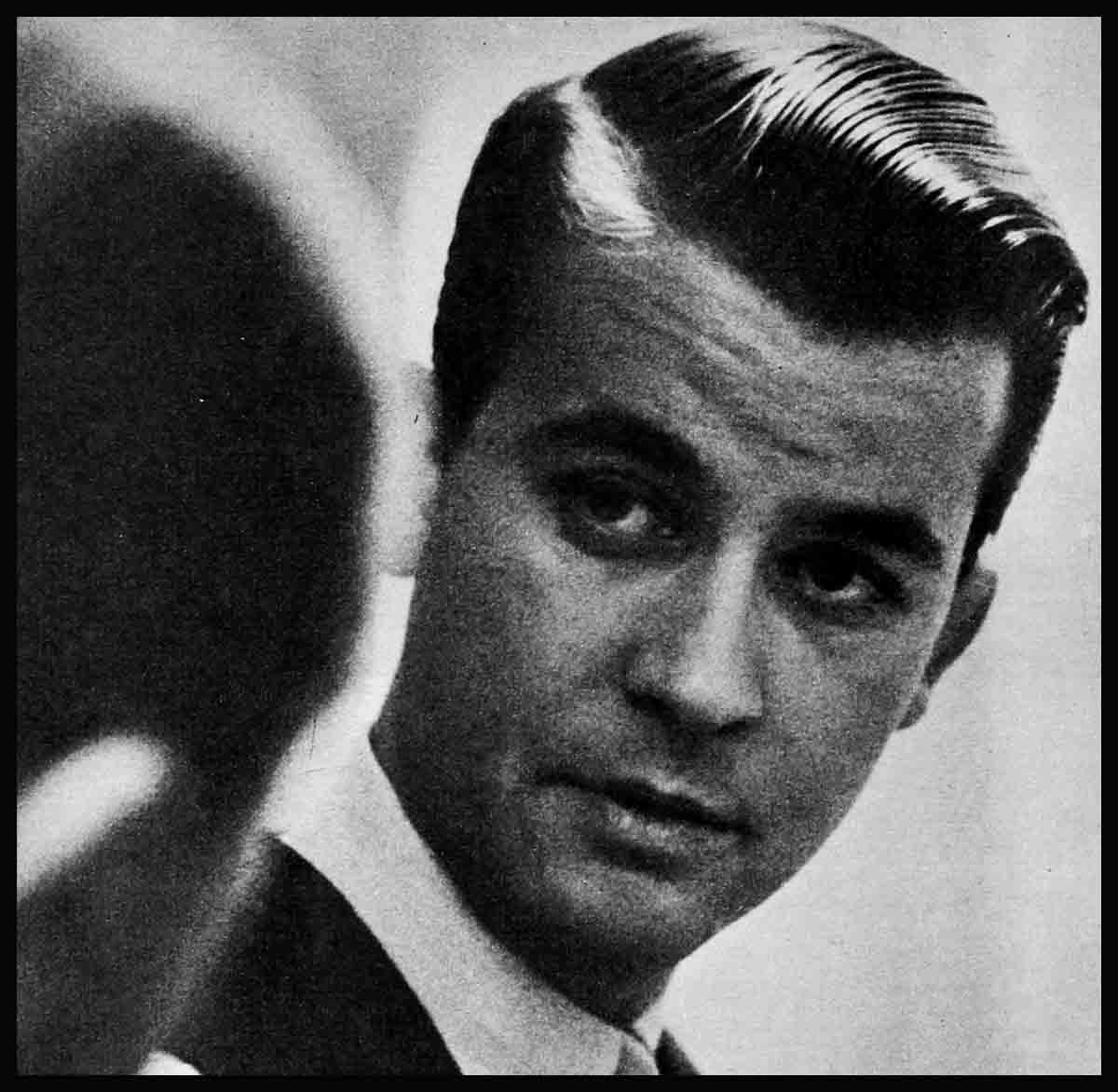

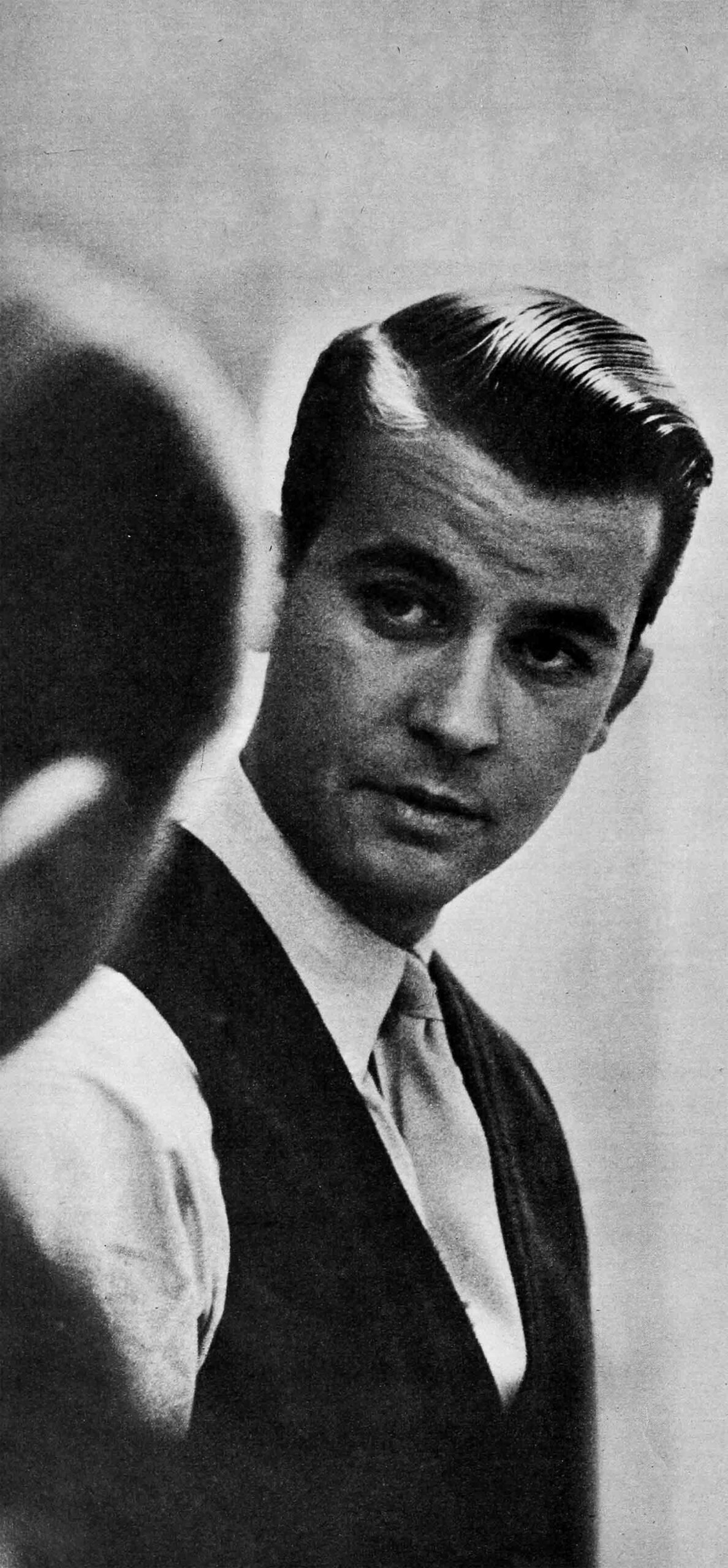

Rock Around The Clock With Dick Clark

Dick Clark drained his coffee cup in a gulp and glanced at his watch. Nine o’clock. Across the dining room table, his wife, Barbara, smiled. “You have time for another cup. And a piece of toast. Do eat more, Dick. You need it.”

He grinned. “Okay, honey.” Barbara was right, as always. When a guy puts in about eighty hours a week in the hectic world of television, personal appearances, and rock ’n’ roll music, he should keep up his strength.

He frowned as he buttered his toast. “You know, honey, I think I’d better do something about that nail-biter today . . .”

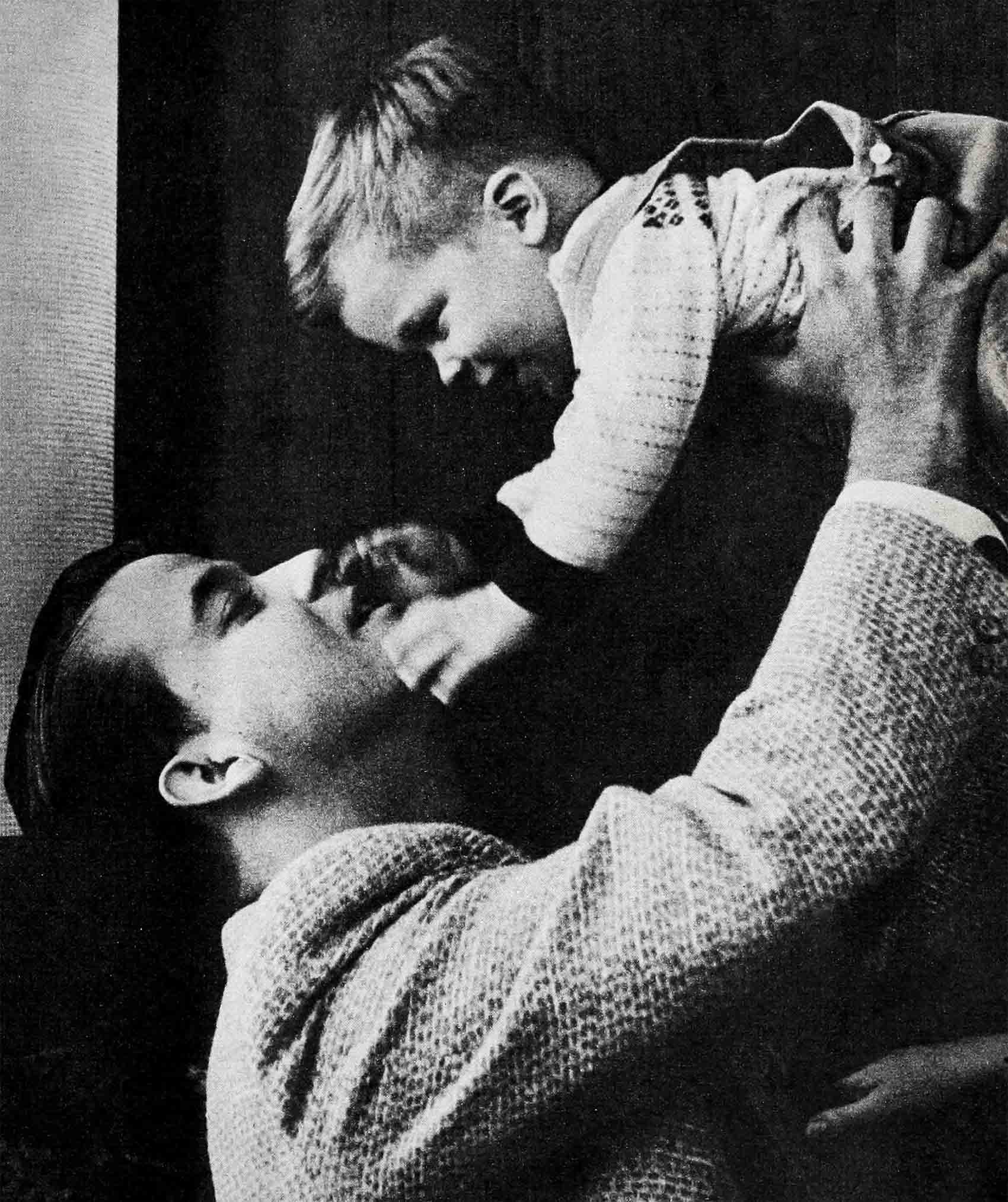

His words were drowned out by a joyful squeal. Young Richard Augustus Clark II, a hepcat of sixteen months, was having himself a ball “dancing” to the music of the hi-fi. “Look at that, Bobbie,” laughed Dick. “It’s mostly footpatting and wiggle, but he gets the beat.”

Dark-haired, blue-eyed Barbara, so calm and serene that even the combination of an extra-lively son and an extra-busy husband doesn’t phase her, had already moved to the door, with Dick’s coat and briefcase ready. Dick gave little Dickie a big hug and kiss, and rushed to the door.

“Will you be home to dinner?” Barbara asked, as he kissed her goodbye.

“I do have to emcee a record hop at Lebanon, but that’s only ninety miles. Yes, you can count on me tonight.”

“It’s the first time this week!” cried Barbara. “I’ll have something special!”

He drove away from the two-story apartment in Drexel Hill, a spacious new development of modern row houses on the western fringe of Philadelphia, a pleasant, unpretentious neighborhood peopled by young folks who work in TV, radio or other branches of entertainment. There are wide lawns, and a fenced playground where the mothers gather with their children.

As he passed through the quiet, treelined streets, his brain was already buzzing with the thousand-and-one details of his multiple role of entertainer, business man and—by popular demand—teenage adviser.

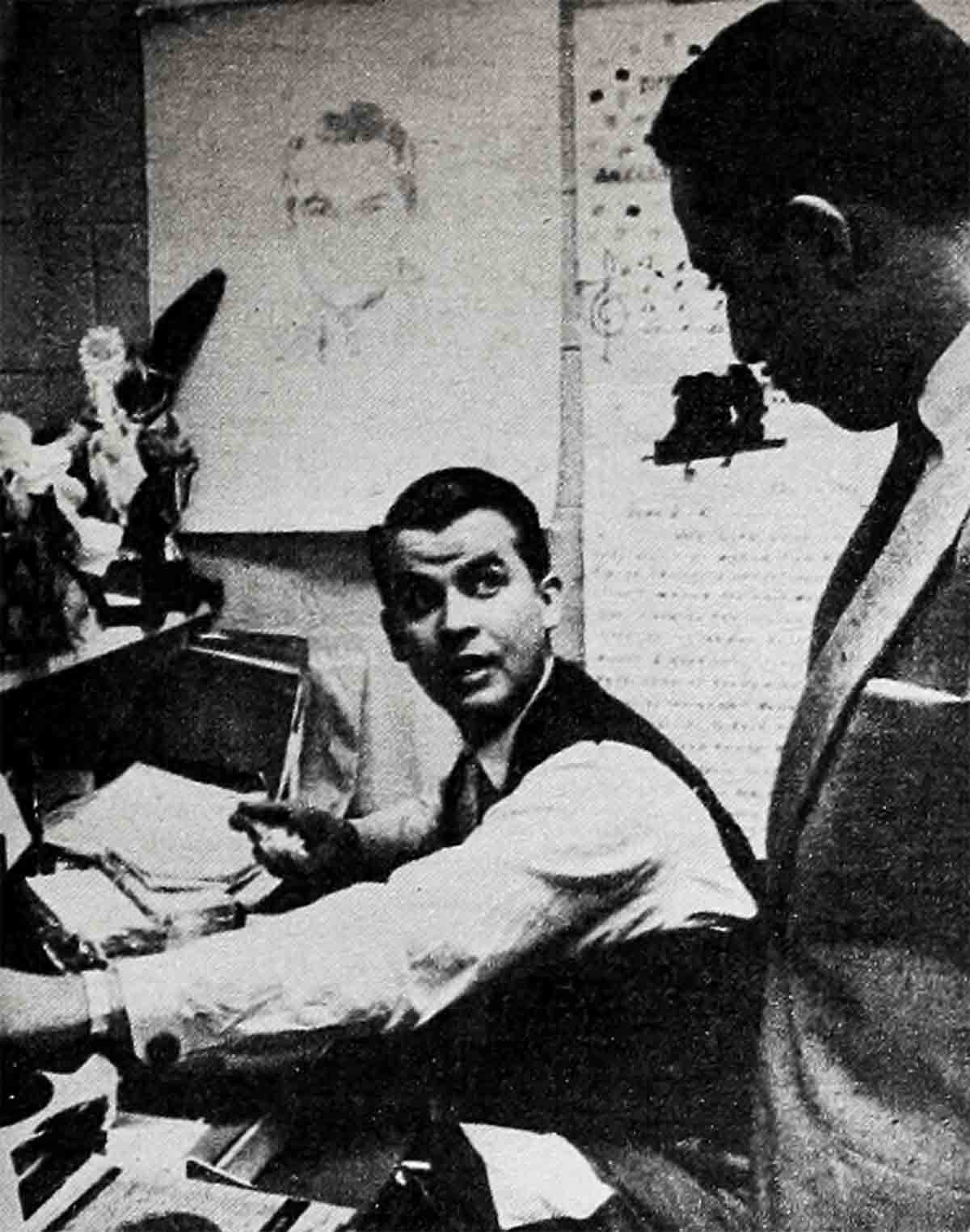

By the time he arrived at WFIL’s sprawling studio at Forty-sixth and Market Streets, he was all businessman—in the most unbusinesslike office anyone could imagine.

“Watch your head and feet!” Dick called out the warning to a record distributor, making his first bewildered entry into the Clark domain.

Stepping gingerly around a stack of mailbags, the man stared open-mouth at a pink chintz hepcap with its donors’ names embroidered all over, dangling from wires strung across the room, along with a branch from a cotton plant, a map of Texas, a menagerie of stuffed animals, an autographed football, and a giant pair of booties with feet half a yard long. The walls were covered with a six-foot postcard and a collection of hats.

“We’ve got a lot of stuff here. The kids send it in,” Dick explained, adding with a sheepish smile, “You see, we’re sentimental. We keep it all right here.”

Unperturbedly brushing dangling objects from their heads, two secretaries and four fan mail clerks were busily at work. Two additional desks faced a wall. At one, producer Tony Mammarella already had a turntable going, monitoring new recordings. Dick settled at the other.

The record distributor ducked under a three-foot paper heart, and sat down beside him. “Dick, we’ve got a new one we thought you’d like . . .”

The man was tall, and the red paper heart hit him on the ear. He squirmed. “Great little combo . . . absolutely new sound . . .” he went on valiantly. The heart, emblazoned with huge letters, “We Love Dick Clark,” kept bumping him on the head. Finally, it fluttered to the floor. Still carrying on a serious business talk with the man, Dick got up and carefully replaced it.

Awaiting his turn to tussle with the red paper heart was a representative of another company, and several more paced the corridor. In the fiercely competitive record business, Dick is a primary target. He estimates there are now 2,000 companies, and all of them want their new releases and new artists on his show. And no wonder! Last summer, when “American Bandstand” was new to the ABC-TV network and Jerry Lee Lewis was new to recording, he played “Whole Lot of Shakin’ Goin’ On” and 5,000 records were sold in Philadelphia alone the same afternoon. When music publisher Jack Lee’s thirteen-year-old daughter, Nancy, watched the kids on “Bandstand” dance The Stroll, she wrote a song to match. The Diamonds recorded it, introduced it on the show, and sold a million-and-a-half records. There are many more success stories, equally amazing.

The word is out that Dick Clark can make or break a record. So great is his power that a worried record executive exclaimed, “We’re raising a monster who can destroy us whenever he chooses!”

At his desk, “the monster” was anything but. All his visitors got a hearing, with polite attention. As the last one filed out, his secretary, Marlene Tetti, came in with a sandwich. Dick’s lunch.

“Marlene,” said Dick, “Did you ever bite your nails? I’m trying to find the best way to tackle this thing.”

“Sorry, Dick, I didn’t,” she answered. Just then the phone rang. Long distance from Texas. A disc jockey.

Propping the phone on his shoulder, Dick munched his sandwich while he listened. “Sure,” he said, between bites. “I’ll be glad to listen to your kids’ record. Just send a recording, put out by a commerical company. It can’t be tape. It’s got to be ready for people to buy. On sale. Now, about that record hop. I would if I could. I’d sure like to. No, it wouldn’t cost you anything. But man, I’m on the air six days a week. I just can’t go farther than 150 miles a night . . .”

When he finished the call, fan mail supervisor Audrey Kingsley was waiting with a basket of letters. Audrey and her crew of four handle about 35,000 pieces of mail each week. Some letters, such as requests for photographs, go through automatically. Dick attends to the “specials.”

He grinned at Audrey. “So here’s the pulse-beat,” he said. “Do you girls realize you do the big job around here? This is how I know what people want to hear!”

Again he was interrupted by the brrring of the phone. An ABC executive was calling. As Dick listened, his face lit up with a big smile. “You’re not kidding?” he asked. “Why, thats wonderful! Thanks. Thanks very much.”

He turned to Audrey and Marlene, who had come in with more items to be discussed. “Well, what do you know!” he said. “The latest report is that we’re getting 8,000,000 viewers for the afternoon shows, and 20,000,000 for the Saturday night show. They tell me that’s the highest rating any daytime show has ever had, the only one that can compare to a night show. Isn’t that something? And that’s not all—our rating almost tripled over the previous month—and our daytime show rating is equal to all those on the other networks, combined!”

Tony Mammarella came in. “Time to go in, Dick. You ready?”

Dick sighed. “I’m sorry, girls. We’ll have to finish this work later.”

Inside the studio, cameramen were setting up for rehearsal of commercials. Dick called a stagehand’s attention to a pennant torn loose from a riser of the bleacher seats. “Can you tack this up before show time?”

He turned to Tony. “Kids who send them look for their own pennants, and I don’t want them to be disappointed. I think they’re great, too. Did it ever strike you, how they sound like a poem from Carl Sandburg about the wonderful face of America?” Dick read them off: “Skowhegan, Evander, Cumberland Falls and Sanford . . . Jo Byrns, O. J. Roberts, Jim Thorp, De Veaux . . . Thousand Islands, Sandusky, St. Louis Zoo . . .”

The stage manager interrupted his chant. “Okay, Dick. You’re on.”

Two-and-a-half hours (counting the local show) is a long, long TV stint in any man’s TV language. But Dick has the aid of the kids.

The first bunch rushed in. They’d been waiting outside the door. The next crowd dribbled in by twos and threes. Some Philadelphia schools dismiss by 2:00 p.m. Almost all classes are out by 3:00, and shortly the studio capacity of 150 is taken.

There was giggling and chatter as they took their places in the bleachers, but it was an orderly crowd. The boys wore jackets and slacks, the girls well-pressed pretty dresses, or blouses and skirts. (Jeans are barred.) Some of the girls put on heavy make-up for the cameras, others didn’t even wear a touch of lipstick.

Tony Mammarella’s quick eye spotted a boy chewing gum vigorously. “Hey, you know that doesn’t look good on camera. Get rid of it.” Even though a gum manufacturer now sponsers the Saturday night show, the studio rule against unsightly gum-chewing has not been relaxed.

Audrey brings in a packing box full of mail, and there are little squeals of delight as the kids line up around a table to get their packets. Many people write to them when Dick introduces them for the spotlight dances.

“Ready, everybody!” called Dick, as the minute hand sped toward the zero hour of showtime. And “American Bandstand” was on.

He watched the cute couple who led off the spotlight dance. Yes, there she was. Great little dancer. Pretty, too.

When the dance ended, he called the girl to the microphone. “How do your hands look today?”

His tone was teasing, but instinctively, the girl put her hands behind her back.

Dick persisted. “Are you still biting your nails?”

Shamefaced, the girl nodded. Dick grew more serious. “You remember, weeks ago, I promised you a prize of five dollars if you stopped it?”

She nodded again. “But I also told you,” Dick went on, “that if you kept on biting them, I’d embarrass you by making you show them to everybody. Well, hold up your hands.”

As the camera moved in for a closeup, the candlepower of the girl’s blush all but burned out the picture tube.

Dick patted her on the shoulder. “How’s about making that bet all over again? I still think you can do it. Let’s be sure your nails look better next time.”

To the girl, that second chance made all the difference. She smiled a million-volt “Thank you.”

At the end of the show, fifty records had spun, but when Dick left the studio, he wasn’t through. A boy and girl were waiting for him in the hallway.

“Dick, have you got a minute?” asked the boy.

“We know you’re terribly busy,” the girl put in, “but this is so important.”

“Come on into the office,” said Dick.

He led them through the crowded, busy place to his own particular corner. “Shoot. What’s the trouble? You seem worried.”

“It’s my father,’ the boy blurted. “He wants me to go to college.”

“It’s my mother,” said the girl. “She’s afraid we might get into trouble.”

“And you want to go steady,” supplied Dick. He had been through this before, but with each couple, the story was just a little different, the kids, the circumstances were different. Talking it out would take time.

Excusing himself, he asked Marlene to get him coffee and another sandwich. He picked up the phone and called Barbara. “Honey, I hope you haven’t started dinner . . . Yes, something has come up. I’ll not be able to get home. But just a minute.” He fumbled through the stack of unanswered letters. “What do I tell a woman who says her daughter’s got brown hair and brown eyes but is tired of wearing brown clothes?” He made a hasty note. “Yes, I’ve got it. How’s Dickie? Fine, see you later. Don’t wait up. ’Bye, honey.”

Ahead of him were a dozen office details, the task of emceeing a dance until midnight, a 180-mile drive proposition, both ways. He’d be lucky if he’d get home before 2:00 a.m.

But at the moment, he wasn’t thinking about that. Two “Bandstand” kids needed his guidance. He turned to them. “Now, about going steady. You know, there’s a lot to be said on both sides. Bobbie and I think we were lucky. We went steady for a while, then we broke up and saw other people, then we came back together, finished school and got married. We sort of feel we had the advantages of both . . .”

And he went on to tell them how he and Barbara Mallery had met at a Halloween party when he was a junior at Davis High School in Syracuse, New York, and, after a Christmas party and a New Year’s party, made up their minds to go steady. Dick smiled at the boy. “I guess I felt pretty much the way you do. I’d made up my mind already that what I wanted more than anything was to get into broadcasting. I’d always been crazy about music. Before we moved to Syracuse, we lived in Mount Vernon, near the Arthur Murrays. Mrs. Murray gave me a course of dancing lessons on my thirteenth birthday. That started it. When I was in high school, I started to collect records.” He chuckled. “Now I have 15,000!”

Then he became very serious. “So, you see,” he went on, “maybe college didn’t look very important at the time, especially since my dad was already in broadcasting. But I was wrong about that.”

He turned to the girl. “Bobbie’s mother was against going steady, too. She told Bobbie she was missing a lot, going with just one boy.” He looked at both of them. “I think that influenced us. But I think, mainly, we were afraid of the intensity of our own feelings.”

Dick went on to tell how they had decided to break off, and how they were separated by distance when Mrs. Mallery, a widow, moved her family to Salisbury, Maryland, and the Clarks moved to Utica; how he had gone to Syracuse University (“Then I realized how much a college education means, no matter what you want to do”) while Bobbie went to Salisbury State Teachers’ College; how they had taken up steady-dating again when she transferred to Oswego State Teachers’ College. He told how college had helped both of them, because he got his first announcing job on a campus station, and, when after a year at Utica station WKTV, he got a job with WFIL in Philadelphia and he and Bobbie were married, Bobbie was able to work as a second grade teacher for a while to help get them off to a good start.

“So you see,” Dick concluded, “when this seems like a big problem at the time, it may not be so big as you think, and everything can work out for the best. The main thing is not to act in haste, or in anger, and try to do what’s right. Now, will you try to do that?”

“Oh yes, Dick, we will!” the two chorused.

He watched them as they walked away, hand in hand, happy as larks. “I only hope they’ll be as happy as we,” he thought. Then, with a burst of renewed energy, he went back to the papers on his desk. Barbara and Dickie would be waiting . . .

It was eight o’clock when he dashed up the walk to the apartment in Drexel Hill. “Daddy! Daddy!” cried little Dickie.

“I let him stay up late,” Bobbie said as he kissed her. “He had a long nap, and it’s such a thrill for him.”

Dinner, kept piping hot—Bobbie’s learned to stick to dishes that “keep well”—was ready to serve. Dick had just time to eat it before dashing away on the long drive to Lebanon.

Weary as he was, he perked up the instant he entered the dance hall. The beat of the music, the high spirits of the fresh-faced teenagers, worked their magic, as always. He remembered how people often think he’s younger than his twenty-nine years. “This is the secret,” he thought. “These kids keep me young. And I suspect a good dose of rock ’n’ roll music would help a lot of folks.”

And, on the long drive home, the music went on, pouring from his car radio, helping to fight off fatigue and making the trip seem shorter.

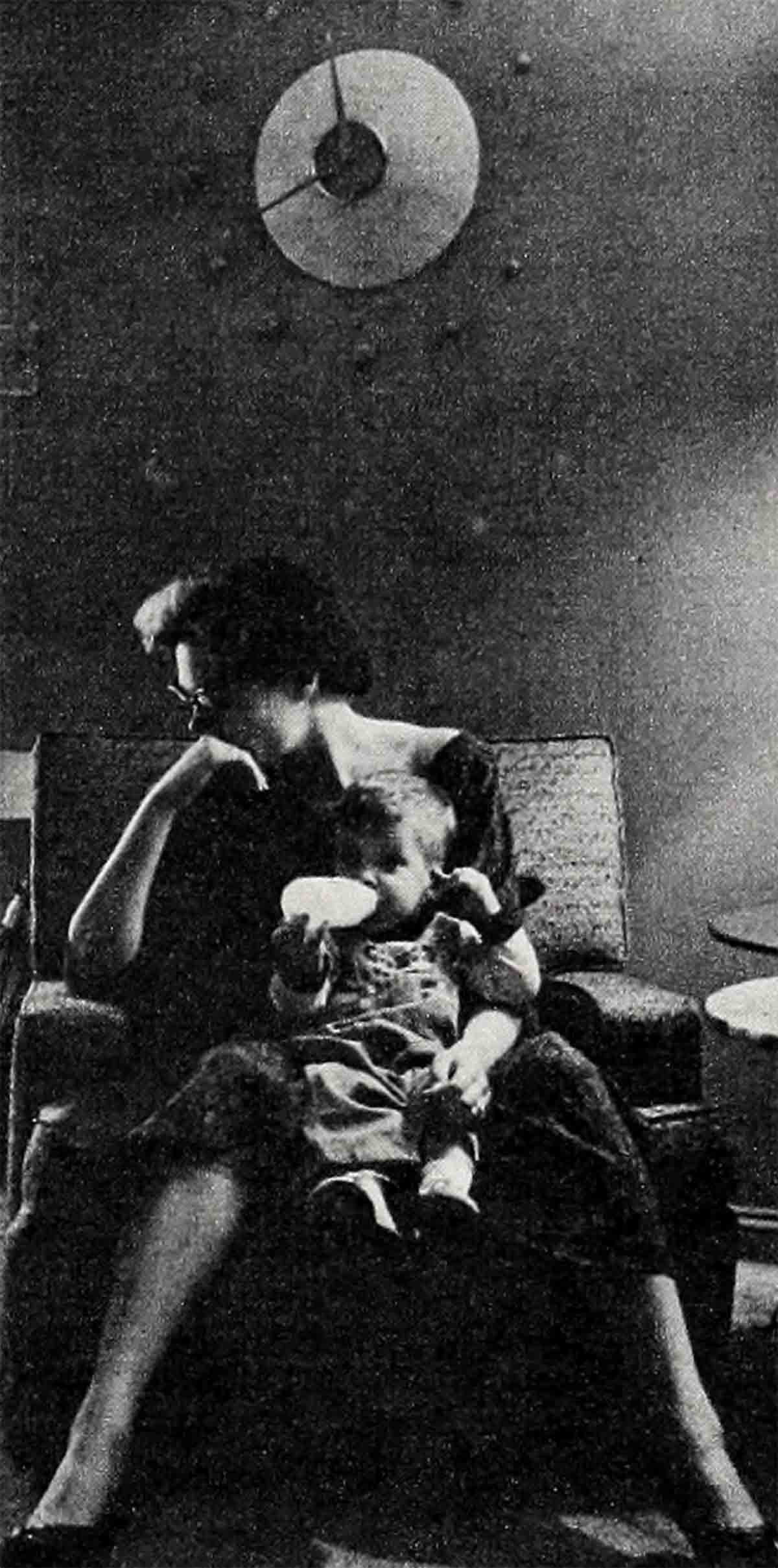

He tiptoed into the house, but Bobbie, asleep in an easy chair before the TV set, was awake instantly.

“Honey,” he chided gently. “I told you not to wait up.”

“But the Late Late Show was so interesting,” she began, and they both laughed, because it was exactly the same thing she always said.

Bobbie had fixed a snack, and they munched contentedly, while Dick talked about his day. Suddenly, in the midst of telling her the good news about his ratings, he broke off. “Honey,” he said, “about that nail-biter. Do you think I was too harsh? Did I do the right thing?”

Barbara laughed. “Oh, Dick, you never do stop worrying about those youngsters, do you?”

She took his hand. “But you know,” she added softly, “that’s one big reason why I think my husband’s a great guy.”

THE END

—BY ALEX JOYCE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1958