The Wolf At Farley Granger’s Door

Venetian Countess Marina has twenty-eight pocketbooks, loaded.

Accessories to this strategic stuff are titian hair, aquamarine eyes to match her name, a treasure-stuffed palazzo in Venice, a house in Paris, one in Rome, a villa for summers in the Italian hills, another for hibernating among orange blossoms and Arabs in North Africa.

The Countess is not without shelter and carfare.

Of all her treasures. the one attracting the most attention now is her grey chromium, red-leathered convertible. It contains Mr. Farley Granger.

Placed in his service by the Countess, it enables him to highball from location each evening to the crested motorboat waiting in the Venetian canal.

Romances between well-muscled, well-heeled young Americans and European countesses, not so young nor so solvent, are old seasoning for Sunday supplements. This is no such horse-radish.

Countess Marina Cicogna-Mozzoni is nineteen; her title is authentic and she holds it in her own right along with her properties; she is related to the noble Volpi family which can shoot marbles with Rockefellers.

In her palatial bedroom a maid attends her rising in the morning and some twenty others stand by to assist her through the day.

One evening, telephoning Farley’s hotel on location, the Countess was told that Mr. Granger was working that night.

“What do you mean, working?” the Countess inquired.

No snob, the Countess is not so insulated in velvet as to be unaware of work, a curse on man since that sorry affair in old Eden, but she probably thought night work was laying Adam’s curse a little heavy on Farley.

The Countess gets around. A cosmopolite, though only nineteen, she knows America and Europe; her name pops into Cholly Knickerbocker’s news during the New York shindig season, and last summer she made a safari to Hollywood. On a set at Warner Brothers studio Farley was presented. Neither felt a temblor, they say, though it was earthquake weather as usual in that jungle of steaming passion.

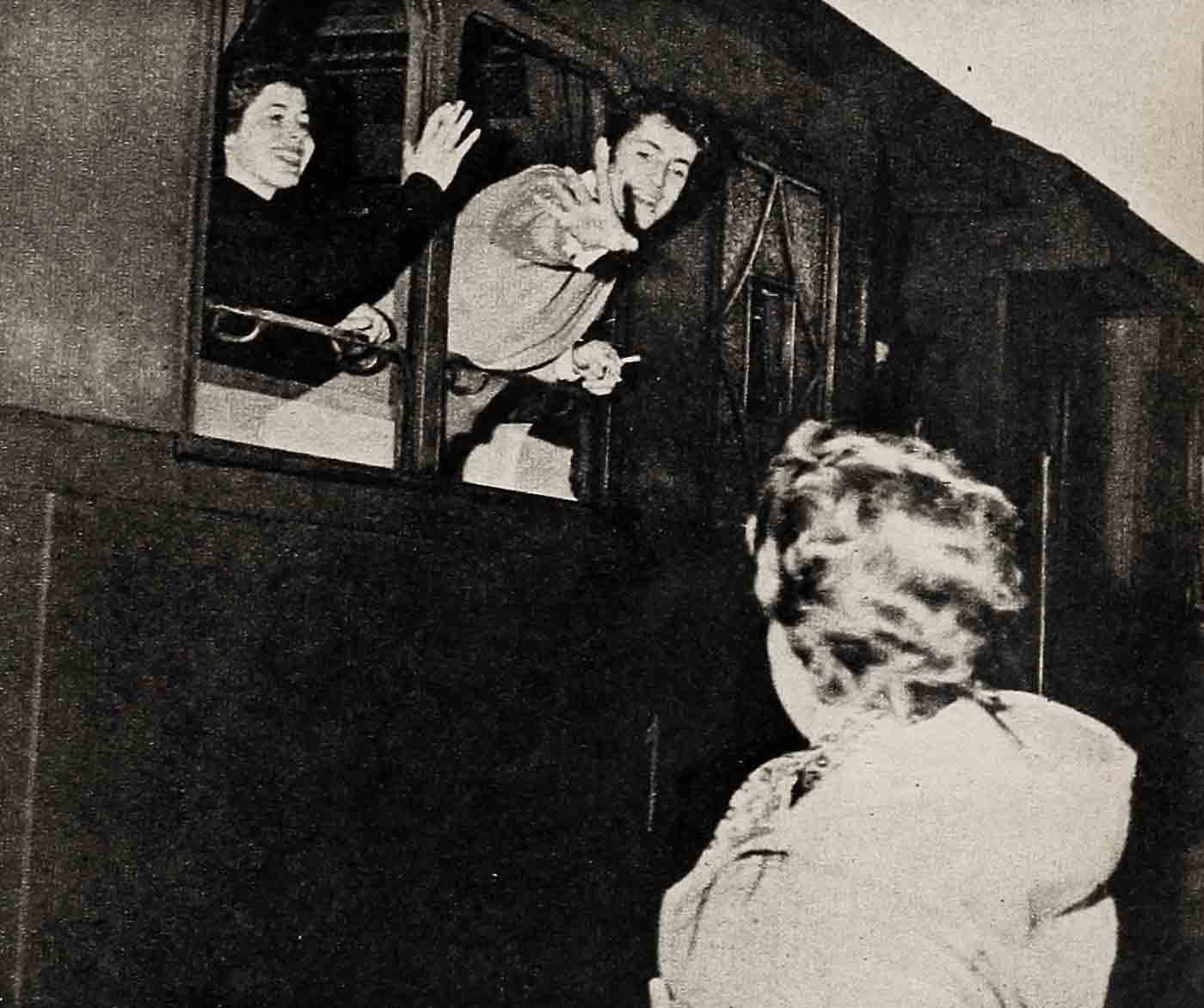

On August 15, Farley flew to Europe to make a picture in Italy. Corks popped salute in Paris, TWA poured vintages in a party to honor him, Zizi Jeanmaire for whom he acted as ballet master in Hans Christian Andersen danced him around the Champs Elysées and Montmartre.

From Paris Farley flew to Venice for the International Film Festival and the annual Venetian regatta. He fell sick in Venice, happily. The telephone rang. Someone said, “The Countess is calling.” Farley got well.

They went dancing at the grand ball in the Volpi palace. Then a gondola sequence of luna-looking with music from serenaders floating at a discreet distance.

At the parties in the great Venetian palaces, at the theatre and yachting, tennis and bathing on the Lido, Farley was not alone in the queue winding round the Countess. There were princes, millionaires, playboys. And Errol Flynn. And Orson Welles. These old operators in service amour, bearing wound stripes and service ribbons, with now and then an alimony attachment, make Farley look a rookie although he must have had sound training during his long enlistment with Shelley Winters.

Though Farley had to quit the field before the finals he left in the Countess’ car with promise of daily telephone calls.

With all her pokes and palaces you would think the Countess had a clear line, but when she calls Farley she gets Janet Wolfe. Everyone gets “the Wolf.” She drives the Countess’ car, accompanies Farley to the set, fetches him raw eggs, interprets, sits in on interviews and dines and dances with Farley. She has even climbed on to the screen with him in a newsreel.

Officially she is Farley’s “Public Relations.” After her newsreel bow, newspapers received an anecdote from her. Seems the hotel maid on seeing them at the movies exclaimed, “Why there is room No. 134 and room No. 128!”

It was corrective news for people who may have thought their rooms adjoined because of always getting “the Wolf” when calling Farley.

An old mug from Hollywood’s Tobacco Road dropped into the hotel to investigate the status quo. He called Farley and sure enough didn’t get. A buoyant voice said she was too beat up to see him for a couple of hours and then Farley would be back from location.

Turning from the desk phone the mug recognized a round little Italian who was a pooh-bah with the Granger company.

“What goes with Granger?” asked the Tobacco Road bounder.

The pooh-bah regarded him with the baleful eye of a ruffled pigeon:

“Of Mr. Granger I do not speak; Wolfe speaks,” he said with clenched teeth. Then, puffing dignity, he added: “For me they are two steps down, Granger and Wolfe. I speak for Mr. Visconti the director, for Miss Valli the actress.”

Feeling a rift in Italo-American amity the boulevardier of Tobacco Road suggested a healing martini. Warmed by sentiment and martinis, the little man gave:

“I am at the service of America and Hollywood,” he said. “Of Granger and Wolfe I speak nothing. It is because here in Italy, as with Hollywood which we respect much, we do not likes smothers on sets.”

The mug melted the Italo-prose in a sip of martini, swallowed a superfluous “s” and said:

“But ‘the Wolf’ is not Granger’s mother.”

His pal shrugged, rocked his hands in the air, and said: “Is same—public relations, agents, smothers: We know that in Hollywood it is not permitted these in studio. No?”

“They seep in,’ said the mug, “guns blazing.”

Suddenly the little man glowered at the descending ascensore and scurried into a far corner. Out of the ascensore shot “the Wolf” like a guided missile. She had a casing blue eye and she wore a steel blue matching gown. The face was not as young as the voice on the phone, but the body was svelte and rhythmic.

She flung a hand to the mug, gave him her back, raced toward a man sitting elegantly aloof. For him she spread a wide smile which, with her small turned-up nose, gave to her face an Irish urchin look suggesting an elder Jane Withers.

After a few minutes of crouched discourse with the gentleman she raced back to the mug.

“That is Visconti the director. I want the job of dialogue director. He has hired someone, but he likes me,” she said, her fingers gesturing to bosom, pleasing in the low cut gown.

A young man drifted unnoticed into the lobby. He wore brown cords and a sport shirt of shrieking greens, blues and dashes of scarlet. It might have been titled “The Battle Of The Parakeets,” and it might have set Bing Crosby to gnawing knuckles in envy were Bing not color blind. Personable, tall, bland of face, looking not more than twenty-one, he might be any one of the good looking young Americans prowling around Europe. There was no professional aura about him.

“There’s Farley now,” said “the Wolf.”

Farley smiled and sat down. “The Wolf” ordered drinks. Farley declined. He had only a chance to say he found Italy marvelous, that he was playing the part of a monster which he found marvelous and that he was glad to get away from Hollywood which is chaotic now, when “the Wolf” reminded him that he had a costume fitting upstairs.

He excused himself. “I will come down as soon as it is over.”

“The Wolf” flung him a look, said he had other business.

“Then I will say goodnight now,” he said, returning to shake hands.

“The Wolf” said she must interpret for him, as the costumer spoke no English. She spun away without a bow or a buona sera.

When she had vanished the little poohbah emerged from his corner, a gleam in his eye, not a gleam of triumph but a gleam of sympathy.

“You can talk with Farley on the set tomorrow,” he consoled the mug. “You will be my guest. I will send a car for you at noon.”

At noon when the car arrived it was the Countess’ car, “the Wolf’ was at the wheel, and the little pooh-bah was a dump on the back. Seat.

On the drive to the villa Valmarama, where scenes. were being filmed, the little man draped scarves over the bare brown shoulders of “the Wolf,” or removed them, according to her temperature and mood. For this he got the free ride and a grazie.

Italians seem uncertain whether to address “la Wolf” as signorina or signora. She herself murmurs vaguely of having had “husband trouble.” Says she was a washout in Hollywood where she did something to scripts in the Fox studio. In 1950 she shook free of scripts and husband trouble by joining up with the Red Cross for service in Italy. She drove a jeep, which she turned bottom up, denting jeep and all occupants except herself. “La Wolf,” you feel, is of quality non-dentable and non-shrinkable.

After her distinguished service for the Red Cross she shipped back to New York. There Farley called her up and invited her to join him on his first film expedition into Italy.

“I jumped at the offer to get back here,” she said. “I adore Italy.”

“And Farley?”

“Old friends,” she said. “We’ve known one another ages.”

In the villa Valmarama, a maze of vast rooms frescoed by pupils of the Veronese school with bare-bottomed babies and pink fleshy mamas of the Mae West school, “la Wolf” raced for the director on her campaign, no doubt, for that dialogue director’s job.

Farley appeared on the set in the uniform of an Austrian officer of the year 1866 when Italy fought the war of her Risorgimento against Austria.

His natural altitude of six-feet-two was increased by high military cap and accentuated by long white cape. He was as imposing as the Empire State building.

His sky-blue pants were so tight they appeared to be painted on his legs. He lowered himself into a chair with apprehension.

“They say the material is strong,” he said. “I hope.”

The picture for which Tennessee Williams wrote the script and dialogue is from an Italian novel titled Senso—roughly Sensuality in English. Farley’s own current romance so resembles that of the picture a Hollywood press agent would be suspected of cooking it up for publicity. In the film, he makes love to a rich Venetian countess and takes her money.

Of course Countess Marina’s twenty-eight pocket books are safe, none missing. Mr. Granger is no monster in person. The Countess did not give him her car though she did offer it for 1,500,000 lire, around $2500, which is three thousand less than she paid for it.

Being no monster, Mr. Granger replies like a gentleman to all inquisitors. The Countess is a friend. A wonderful person. A noblewoman in the true sense of nobility. Telephoning him when he was ill in Venice, a stranger to the city and a person she had met only casually, was in the tradition of noblesse oblige plus the natural kindness of a sweet nature.

“La Wolf” also is wonderful, an old friend, who was invaluable to him in Italy. He calls her Janet.

“Janet!” he howled suddenly. “Janet, get me a couple of raw eggs. I have had no lunch. Janet!”

Janet apparently was on business of her own at the moment.

Later when asked if she thought Farley would buy the Countess’ car she smiled and shook her head. This led the mug to observe that Farley wouldn’t need to buy it if he married the Countess.

“She will not marry him,” said “la Wolf” authoritatively. “They marry in their own crowd.”

The Countess’ car was all right, she said, a special job, but Farley thought he wanted an Alpha Romeo. “La Wolf” thought that foolish.

“We,” she said plurally, “are going to buy a Jaguar.”

THE END

—BY HERB HOWE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1954