The Three Days Jackie Hid From The World

Our story of the three days Jackie Kennedy hid from the world, our story of her biggest crisis as a wife and mother begins on a Tuesday morning at 8:45. That was when McGeorge Bundy, President Kennedy’s advisor on national security, hurried out of his Office in the West Wing of the White House, rode the small elevator up to the second-floor living quarters and rushed into the President’s bedroom. The President was in bed, in pajamas and robe, reading the newspapers.

What Bundy showed the President was incredible! Aerial photographs taken over Cuba, revealing forty fifty-two foot medium-range missiles nested in mobile launchers and aimed directly at the United States. The slim but powerful weapons, with one-megaton warheads, were capable of snuffing out the lives of seventy-five million Americans.

In addition, the pictures clearly indicated the Russians were rapidly constructing half a dozen other bases for even more destruc-unsuspecting American cities from Coast to Coast.

A short three hours later, the President was seated in his rocking cnair at a top-Ievel, secret conference with his advisors. The problem was to prepare to meet the Russian threat without letting the Soviet Union know that we even suspected that they had broken their diplomatic word and were transforming Cuba into an arsenal of offensive weapons. So it was decided that the President would keep his appointment with Cmdr. Walter M. Schirra, the astronaut, his wife and the two Schirra children. The President even went so far as to take his visitors to see Caroline’s ponies. What could be more peaceful?

It was also decided that the President should perform other public motions expected of him, while behind the scenes, his best political and diplomatic experts prepared for the worst.

On Wednesday, the President made campaign speeches for Democratic candidates in Connecticut. On Thursday he presented aviation trophies, conferred with his Cabinet on his domestic problems, received official visitors and even met with Russian Foreign Secretary Andrei Gromyko. The latter assured him that his country was interested only in supplying (defensive) aid to Cuba.

Although the President was fully aware that at least twenty-five cargo ships were at that very moment en-route to Cuba, many of them loaded with “offensive” weapons, and even though he had the photos of the Soviet missile sites right in his desk, he didn’t tip his hand to Gromyko. Rather, playing his role of an innocent to the hilt, he repeated matter-of-factly that we wouldn’t stand for “offensive” bases in Cuba.

Gromyko, completely taken in by the President’s play-acting, came out of the meeting with a smile on his face and told reporters that the conference had been “useful, very useful.”

But the time for play-acting was running out. The time for real action was nearing. On Friday it was decided that the President would address the nation—and the world—the following Monday; but he still had a few cover-up scenes to perform.

He went to Cleveland for a campaign speech, stopping at Springfield, Illinois, to place flowers on Lincoln’s tomb. all through his appearances in public, the President smiled broadly at the crowds. But once in the privacy of his hotel room he became grim-faced as he immediately phoned his “War Council” in Washington. It was while he was in his hotel room in Chicago that it was decided he should return to Washington the following day.

But what excuse would be plausible? Dr. George Burkley, the assistant White House physician who was with the President in Chicago, inadvertently supplied the motive for the return to Washington.

It was beginning to rain, and Dr. Burkley warned against doing any further out- door campaigning in the bad weather. The doctor was amazed when the President complied meekly with his order, instead of arguing back as he usually did.

Having been given his cue, the President improvised on it. Word went out to Press Secretary Pierre Salinger that the President had a slight infection of the upper respiratory tract (which he didn’t) and was running one degree of fever (which he wasn’t) and that he was cancelling the rest of his trip and flying back to Washington (which he did). Even Salinger was deceived when the President arrived home bundled up in a coat, a hat (!) and a muffler.

Sunday was the lull before the storm. The President polished and repolished his speech for Monday. When he took a few hours out to view a White House screening of “Billy Budd,” even that didn’t distract him—the film opens with a scene showing a warship halting and inspecting a merchant ship.

Monday morning he kept up his “business as usual” pretense. At 1 P.M. he’d taken his swim in the White House pool and acted as if he were enjoying it. (Perhaps he really did. As his friend Dave Powers says, “When he dives in you can see the tension of the day moving away in the ripples.”)

Around 6 P.M. Russia’s Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin was called to Secretary of State Dean Rusk’s office at the State Department. Dobrynin chatted amiably with newsmen before entering; twenty-five minutes later when he came out, a copy of the President’s speech and a letter to Premier Khrushchev clutched in his hand, his face was the color of smudged putty and he snapped at reporters who tried to question him.

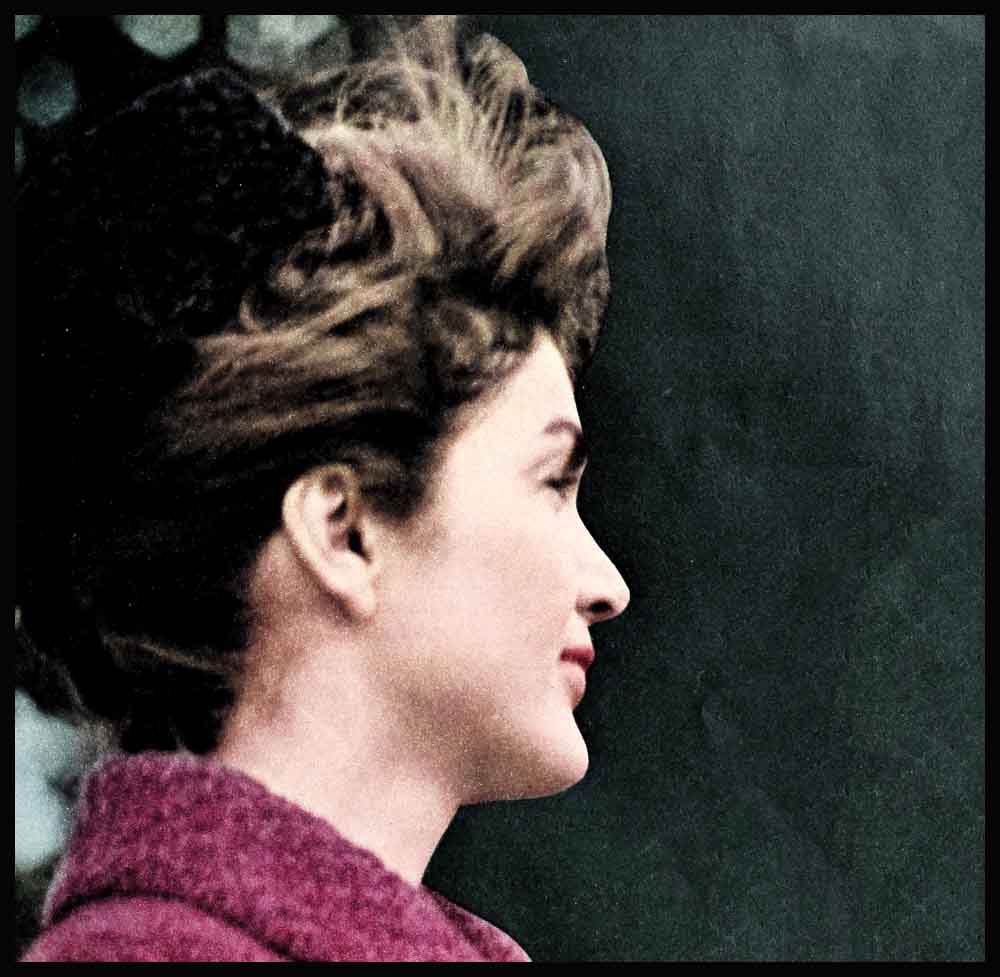

As the day passed and people discovered that the President was going to address the nation on a grave matter, tension was terrible. And Jackie shared the anxieties, the fears and the uncertainties of those millions of others, many of them wives and mothers like herself who were about to hear the President of the United States reveal their destinies. But in addition, Jackie felt a unique frustration.

Like any wife, she wanted to help her husband, to say something to him, to do something that would relieve a little of his terrible responsibilities. Just to be able to touch his hand . . . just to be able to whisper a few words to him—any words, frivolous, silly, it didn’t matter . . . anything to see him smile for just a second—it would make the situation more bearable.

At 6:55 P.M., Jackie’s husband, wearing a dark blue suit, dark blue tie and white shirt, entered his study where the TV camera had been set up. The gray at his temples seemed more pronounced than usual; the lines in his face were deeper. He sat down but got up again, as two pillows were placed in back of him on his chair. A deadly calm settled over the room, broken only by the crinkling of papers as the President ruffled through his speech.

“How much time have we got?” he asked. It’s a simple question, but all at once it’s one that is full of dread. The “we” becomes everybody—all the people in the world—and the answer seems to be contained in the speech that lies before him.

His secretary, Mrs. Evelyn Lincoln, came in with a comb and brush. Mr. Kennedy gets up, goes out for a few seconds to a small washroom and takes a few swipes at his hair.

At 6:58 P.M. the President returned. Technicians gave him the stand-by signal. He was on the air.

At 7:00 P.M., John F. Kennedy told his listeners about the secret Soviet build-up of offensive weapons in Cuba, and called for a quarantine of all vessels bringing armament and war material to that country. Then, in words delivered as calmly as their content was threatening, he warned that “any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere” would be regarded as an attack from the Soviet Union “requiring a full retaliatory response.” Those were his words.

It was 7:15 when the President finished his speech. For a minute longer he remained at his desk, hunched over his papers, rearranging them, but somehow his posture and attitude were those of a man at prayer.

There were no set meetings for him the rest of the evening, but he made and received phone call after urgent phone call until well after midnight

And Jackie had some phoning to do, too. all social events must be cancelled: her reception for the thirty-eight poets attending the National Poetry Festival at the Library of Congress; the State dinner for the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg and her husband Prince Felix; the preview at the National Gallery of Art of the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire’s collection; and her appearance at the International Horse Show where she was to present the President’s gold cup to the winner of the jumping event (she asked her mother to stand in for her at that function).

As she spoke softly into the telephone, Jackie was not yet fully aware that this was the beginning of three days in which she and her children would have to hide from the world. “The world,” for Jackie, has as its center her husband, Jack. Fanning out from the center, as spokes jut out from the hub of a wheel, are her relatives and friends. Finally, there is the rim, the outer circumference, composed of the millions of people she does not know person- ally but who have come to know and love her.

She was forced to withdraw from the world and, in effect, to hide from her own husband. Although in a sense they were as close as ever to each other—sometimes in the same room, sometimes in different rooms just a few hundred feet apart, actually there was a deep and uncrossable gulf between them. He was preoccupied with and responsible for the fate of the United States—and the very future of the world. There was nothing, absolutely nothing, she could say to him or do for him that could ease the terrible weight of decision he bore on his shoulders.

She had to hide from her relatives and friends. Cancelling her social engagements was the initial step. Next there came a three-day period of virtual isolation. No gay dinner parties. No glittering receptions, no formal functions. With the entire nation poised precariously on the brink of war, the first lady, in keeping with the gravity of the situation, withdrew grace- fully into silence and isolation.

Lastly, Jackie put a wall between herself and the public and hid behind it. No romping with Caroline and John, Jr. on the White House lawn. Her daughter’s hi-jinx and her son’s precocity had to be muted and subdued. No statements to the press. No interviews. No photographs. It was a time for solitary meditation . . . a time for prayer.

On Tuesday, the first day Jackie hid from the world, the American blockade of Russian ships bound for Cuba began. Khrushchev ranted but did not act. By Wednesday and Thursday, all America was asking: Will Khrushchev push the button that will set off a nuclear war? When the soviet cargo vessels and the American destroyers and aircraft carriers finally do meet, will the Russians stop—or shoot?

To Jackie it must have seemed impossible to believe that ten days before, her daughter Caroline, with her twenty kindergarten classmates, had “played” at war. That was when Algeria’s Premier Ahmed Ben Bella had been officially received by the President on the White House lawn. As a cannon roared out twenty-one salutes of welcome, Caroline and her chums echoed each cannon clap with a loud “boom” of their own. The children’s “booms”—shouted from the second-floor window—had carried down to the review grounds. Later, Jackie and the other mothers had to reprimand their children. But that was ten long days ago. What now? How could she explain the kind of a “war game” that her daddy was playing in earnest? How much should a child understand?

Jackie knew how horrified her husband felt about the possibility of a nuclear war. “If you could think only of yourself,” he said, “it would be easy to say you’d press the button, and easy to press it, too.” But at least 70 million people were involved (Jack’s advisers’ conservative estimate of the number of Americans who would perish in a nuclear holocaust), and therefore he didn’t want to get drawn into the game at all.

But the Soviets had made their move in Cuba, and Jack had to play, reluctant or not. But how could Jackie make all this clear to Caroline? It was a delicate—extremely delicate—question.

It was impossible not to say something to the child. Her father wasn’t around much of the time—that had to be explained; streets and Stores were almost deserted—that had to be explained; the air was thick with apprehension, dread—that had to be explained. And somehow, in some way, the rumors that our nation might be heading for war must have sifted through to the youngster: that had to be explained.

Suddenly, by Friday, there seemed no more time for explanations and reassurances; time was running out.

In the morning there was a glimmering of good news. A Russian-chartered vessel allowed itself to be halted and searched by the destroyers John R. Pierce and Joseph P. Kennedy (named after Jack’s older brother, a navy flier killed over Europe in 1944; it was from the decks of this same ship that Jackie and her husband and Caroline had watched the America’s Cup yacht races off Newport, R. I., a month before). A little later, word reached Washington that a convoy of Soviet merchantmen carrying arms to Cuba had voluntarily turned about and headed for home.

But by afternoon cold fear numbed Washington. New intelligence reports based on up-to-the-minute photographs indicated that instead of dismantling or discontinuing work on missile sites, the Russians were speeding up their work on the bases to achieve (in the words of the White House) “full operational capacity as soon as possible.”

In short, it seemed as if the United States might have to bomb military bases in Cuba. Reporters were so sure that such an action was contemplated that they didn’t ask if it were going to take place but when it would happen. And late editions of many newspapers ran scare head- lines that we would probably invade or bomb Cuba. It was a dread time for all.

Swift, dreadful nuclear retaliation by Russia might follow.

Now Caroline’s questions had to be answered. (As the Child Study Association of America says in its booklet, “Children and the Threat of a Nuclear War,” “American children four years old and up are aware of a danger to life and they connect this danger with the language of nuclear war: fallout, Russia, radiation, and the H-bombs.”) Questions like: Does fallout hurt? Are bad men dropping the bomb? Is a bomb going to hit our house? Where will daddy go if we’re bombed; will he get to us in time? And: Will I die?

There are many ways in which Jackie could have answered Caroline. Ways that the child psychologists and educational experts recommend. She might have told her that during World War II poison gas could have wiped out all life on the earth, but that it wasn’t used. She might have told her that man has always lived with danger and that he has somehow survived and prevailed. She might have told her that there are calm. rational men like her father who are working to prevent bombs from falling.

But it is most likely that Jackie spoke to Caroline. as she had so many times in the past, about God. God who has more understanding even that daddy and more power even than Mr. Khrushchev. God to whom little girls and their daddies and their mommies can pray for the miracle of deliverance from all evil.

Jackie’s prayers and Caroline’s prayers i and Jack’s prayers and the prayers of millions of other people throughout the world were answered. On Saturday there was more cordial communication between America and Russia; on Sunday the Russian premier sent word that he had ordered all work on the Cuban bases stopped and that the missiles were being dismantled, crated and returned to the Soviet Union. We, in turn, pledged that there would be no attack, no invasion of Cuba.

That morning—Sunday morning—Jack went to 10 A.M. Mass at St. Stephen’s Catholic Church in Washington. Usually accompanied by his wife, people wondered where Jackie was . . . wasn’t she in Washington? That afternoon they learned the answer—Jackie and the children had gone, quietly, secretly. to Glen Ora, their rented estate in Virginia. Usually, Jackie’s whereabouts are known to the press, usually her helicopter rides to Glen Ora are reported as casually as one would report a commuter’s train rides. But that weekend, that fateful weekend, Jackie’s departure from Washington, with Caroline and John, Jr. was not mentioned. From the time of the Presidential announcement of a quarantine—till the day President Kennedy flew to Glen Ora to be with his family—then, and only then, was Jackie in the news again.

As the President relaxed on the beautiful farm with his wife and children—one couldn’t help realize that this was what it was all for—those tense, terrifying moves in the grim game of war. For once before, when he had reached a stalemate in the game in failing to budge Khrushchev at Vienna, the President had said to a friend. “It doesn’t really matter as far as you and I are concerned. What really matters is the children.

—JAE LYLE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1963