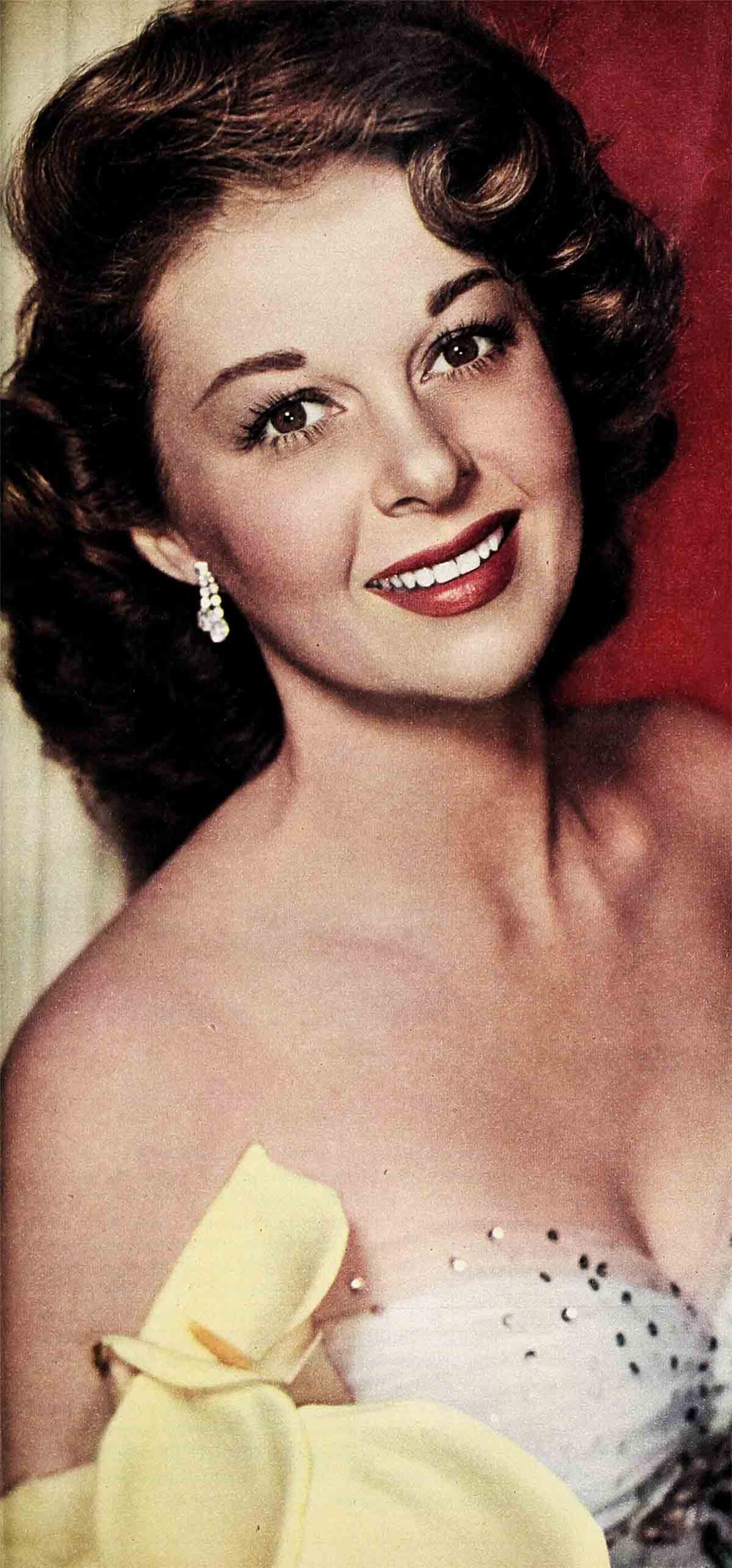

Three Loves Has Susan Hayward

They’re named Jess, Timothy and Gregory Barker, and they’re at the warm heart of Susan’s world. She likes to work, but the men in her life come first and they know it. Secure in that knowledge, they take the rest in stride. Now and then the twins will put up a reasonable squawk. As on the day she started “The President’s Lady” in August, soon after finishing “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” “Why can’t you not work till we go back to school?” They got a reasonable answer, plus the dazzling promise of a fishing trip, and felt they’d engineered a pretty neat deal.

Her solution to the problem that baffles so many career women rests on a rooted devotion to home, husband and kids. At the studio nobody works harder than Susan, nor drops out more completely once the picture’s done. Her free time belongs to her family, and she won’t have it nibbled away by meaningless outside demands. When the phone rings, she calls to Cleo, the cook: “I’ve just left for China!”

Offhand in manner, her speech laced with dry humor, you’d never take her for the sentimentalist she is. Anniversaries are sacred. She and Jess even celebrate the day they met. Stored away in a box are the broken bits of two lovebirds that topped their wedding cake. Till they fell apart, she kept them over the bed. Arden’s Cyclamen is her favorite perfume, because it’s the first he ever gave her. Her first gift to him was a pair of cuff links, his initials on one side and on the other, Francie—the kid who grew with the tree in Brooklyn. Jess still calls her “Francie,” his kid from Brooklyn. Or “Pinky,” for the luminous quality of her glowing skin.

The fact that she’s a movie star makes no impression on her sons. “With a Song in My Heart” was the first Hayward picture they saw. Tim sat enthralled, weeping steadily through the sad parts. Greg asked, “When’s the comedy coming up?” Since Greg’s the sensitive character and Tim’s the battler, Susan has yet to figure out these reactions.

Greg and Tim were seven last February, and they’re so different that Susan finds it hard to think of them as twins. Tim’s five pounds heavier than his slender brother, and more outgoing. Being introduced, he’ll stick out a friendly paw. Greg stands back and cases you before committing himself. Tim’s easier to fathom. Sent to his room for some misdeed, he bangs things around, gets the ferment out of his system and starts from scratch. Greg clams up and broods, thus driving his mother frantic. On the other hand, Greg’s the comic who comes out with cracks. Like all humans, they’re inconsistent. Matter-of-fact Tim’s the book-lover who invested his own cash in a copy of “Tom Sawyer.” Greg, highly imaginative, likes to work with his hands, though given the choice, he’ll sit spinning private dreams which have been known to take a practical turn.

Recently the Barkers bought a Ford station wagon. Greg asked what it cost. Susan told him. “Is that a lot?” he queried anxiously.

“My daddy didn’t make that much in a year,” Susan told him. “Many people don’t. They have to use all their money for food and rent.”

Greg digested this. “You know what? I b’lieve I’ll make a million when I grow up.” “Good luck to you,” said his mother.

That night she overheard her sons in caucus. “You can’t make a million,” Tim was arguing, “unless you invent things. So what’ll we invent?”

“A magic machine,” offered Gregg. “Say f’rinstance a little kitten comes along. Well, you pour this magic water over the kitten and change it to anything you want. And there’s your million!”

Susan and Jess take parenthood seriously, which doesn’t mean solemnly. Their object is to launch into the world a couple of well-adjusted citizens. They agree with the modern school of thought in lavishing love and more love on their children. They disagree in the matter of discipline. Psychologists say don’t spank. Susan says, “I think boys need a good whack on the fanny every so often when they get out of hand. It clears the air and does them good. It’s a kind of protection against their own lack of self-control. I’ve observed kids who’ve never been spanked; to me they seem less secure. Somehow they get the idea that you don’t care enough to exert yourself to whack them. Not that I advocate it as a regular thing. But when the occasion calls for it, yes—if they’re deliberately disobedient, if they endanger themselves by picking up a butcher knife or shooting out of the driveway on their bikes. You can always say, it hurts me worse than you. Tim’s answer to that one is, ‘I’llbet it does—’ Then he laughs. Even Greg’s less upset by a spanking than a scolding.”

What the family does is less important than the fact that they do it together, Sometimes they pile into the station wagon for a trip to the fishing store to look at tackle. Sometimes it’s a tossup to decide who pays for a round of orange juice. The kids are cheerful losers. Their allowance is twenty-five cents a week, but they get a bonus for such extras as keeping the backyard clean. Right now they’re loaded, since the good fairy slips a handsome half buck under their pillow for every tooth they lose. “The good fairy’s mommy and daddy,” Greg whispered to Tim.

“I know, but don’t tell them.”

They have projects, like the garden planted by Tim and Susan. The flowers throve, the vegetables came up cockeyed. It’s daddy, not mommy, who’s blessed with the green thumb. Gregg’s an interested onlooker, free with advice, but unprepared to sweat. Figaro has to be discouraged from helping. Figaro’s the Scottie presented to Susan last Christmas by the boys. Amiably disposed toward all the world, Susan’s definitely his mamma. Let the twins play rough, let Jess give him a look, and he scuttles to Susan, cocking an eye out from behind her skirts. He’s a sucker for lemons. Picks them off the trees, rolls them to the edge of the pool, drops them in and turns around for applause. Everyone, Figaro included, thinks the act is terrific.

Afternoons are spent in and around the pool. No summer camp for the boys. “They’re too little,” says Susan, “and we’re not anxious to be rid of them.” Instead, she engages the seventeen-year-old daughter of their former nurse. She’s young enough to have fun with them, peppy enough to go hiking with them, and responsible enough to be trusted with them. Their program is more flexible than a camp’s and perhaps more varied. And for that inevitable moment when they cry, “What’ll I do now? I have nothing to do,” Susan always keeps something stowed away—a pound of clay, for instance, that costs all of twenty-five cents and provides an enchanted interval.

Susan and Jess together put the children to bed—a ritual that includes hugging, prayers and blessings and a little parley on personal affairs. Like, “Dear God, I pushed Greg, but I didn’t mean to and he bumped his right elbow. Please make it all better.” After being tucked in, there’s another companionable interlude devoted to the day’s doing or to song. Then they’re supposed to go to sleep. Susan circumvented the drink-of-water gag by installing in their bathroom a Dixie-cup machine. For the pleasure of punching out, their own cups, they surrendered the inherent right to yell for water. Of course, you can always yell for something else “I better get up and put my bike away.”

“I don’t think it’s going to rain on your bike tonight, so just relax.”

If Susan says it, they may give her an argument to see where it gets them. If Jess says it, they relax, and their elders settle down for a quiet evening. Jess watches the ball game on TV. Susan reads or sews, and looks up once in a while as the crowd roars. She’s the kind of fan who understands a three-bagger and what the umpire means when he yells strike. Jess can reel off every percentage to the last decimal.

Generally speaking, she’s lukewarm about television. An occasional special program holds her interest, but she’d rather take in a good movie or a play, if there is one, or go to the Hollywood Bowl. Barring brassy jazz, she delights in all forms of music, with maybe a special leaning toward the piano. In her studio dressing room, she wears the Erroll Garner records thin. By the same token, she loves to dance, as does Jess. They both dance well. He has just one criticism to make, and makes it to her. Carried away by the music, she’ll forget who’s leading. “Would you care to try this solo?” he suggests. Abashed, she subsides.

They live simply because they like living simply. Their house is relatively small. Needing more space, they keep half an eye out for a larger one without putting any frenzy into the search. They don’t go in for elaborate decoration. Interested in paintings, they’ve bought some good reproductions of Cezanne, the earlier Picasso and other French moderns. For the rest, their place suits them as is and they leave it that way. Susan’s no slave to her possessions. “To me that’s empty foolishness. There are too many other things to do. It’s a big world. I’d rather see it some day than spend all the money on my four walls and sit looking at them.”

Cleo’s the whole domestic staff, except for her sister who comes in once a week for the heaviest cleaning. Entertainment’s what Susan calls strictly the family type. Her mother and brother live close by, and count as part of the family. Jess has a flock of kinfolk who turn up from China, Alaska or San Fransisco. Their circle includes many longtime friends from the east, and an actor or two—George Tobias. Thelma Ritter.

Dinner parties are small because more than two extra couples crowd the dining room. And informal, because they eat early on account of the boys. On account of the boys, too, they pick their guests “Lots of adults don’t care for dining with children. To us, children are the home. We don’t banish ours for the sake of company. Instead, we ask people who have children themselves and like them.”

When more lavish entertainment is indicated, they take people out. “I’ve never thrown big parties. I don’t feel that, because you’re in the movies, you have to throw them. My idea of home is a place that’s comfortable and relaxing. Being hostess to a crowd, even if you like them all, creates a certain tension. Anyway, it does in me. Life’s full of tensions that you can’t do anything about. When you can, its a little stupid not to.”

Her mood determines whether they eat in on Thursdays—cook’s night off. In an anti-cooking mood, she’s likely to burn herself a dozen times. To eliminate that tension, they go out. Otherwise, she’s an admirable cook, concerned with what her husband and children eat. Feed them well is her slogan, so they’ll have a liking for food. Her own liking for food comes naturally. According to Jess, she’s a gal: with the soul of a poet and a truck driver’s appetite. Once, after a solid meal at the Stork Club in New York, they went with a friend to hear Erroll Garner play. Later they wound up at El Morocco, where Susan consumed a large plate of chop suey and part of Jess’s steak, then cast a speculative eye at the friend’s sandwich. He managed to stuff it down before she could raid it. Between pictures she gains six to eight pounds, and drops it as easily by abstaining from her own cookery.

Being thoroughly feminine, she’s illogical in a way that amuses (and enchants) the male of the species. She insists that her Cadillac be a convertible, and never puts the top down. With the top down, you get all blown to bits and the sky glare’s terrific. Then why a convertible? Because it’s pretty. What else? And let the boys hoot. They don’t hoot at her driving. Jess says she’s better than most men. And if you mistrust a husband’s fond opinion, take the word of a couple of unbiased truck drivers. One came bowling toward her at sixty miles per hour. The other shot out of a side road directly ahead. It was Susan who averted disaster by cutting her car so as to miss them both. They spoke in hushed reverence. ‘“Who’da thought a woman driver could do that?” The remark produced a glow that warmed her for days.

Another compliment she treasures came from a cowboy. “Ma’am, you’d have made a damn fine western woman.”

The traditional western woman is outspoken. So is Susan, who welcomes the same kind of treatment from others. Impatient of beaters-about-the-bush, she’ll hypo them with, “Okay, let’s have the pitch.” At the studio, she’s nobody’s pushover, but neither does she throw her weight around. If she’s got a beef, she’ll ask the director to lunch, thrash matters out with him and settle them. She has the objectivity of the mature. “I try to be honest with myself and others. Occasionally I kid myself, as who doesn’t?” An impartial bystander would guess that she kids herself less frequently than the average.

Fatigue makes her irritable. The time to leave Susan alone is when too much has happened too swiftly, landing her in a state of weary confusion. Up to a point she controls her nerves. Beyond that point she gets a pain in the head and lets go. Humor restores the balance. Like Tim, she finds release in banging things around. Eventually something breaks, which makes her feel like a fool, which makes her laugh. While his temper’s better disciplined than hers, Jess, too, can blow his top. As a vent, he’ll slam into the car and drive where the mood takes him until he cools off. By the time he gets back, Susan’s a dove. To the boys, they invariably present a united front. The boys have heard them discuss differences of opinion. Never have they heard them really quarrel.

In tastes, as in viewpoint, she’s an individualist who prefers gardenias to orchids, and peonies to roses. Jess sometimes slips a gardenia under her pillow, contriving in some miraculous way not to squash it. Best of all, she loves tuberoses. Her favorite color is yellow, which Jess doesn’t like, so she keeps it for solos and wears black or white when with him.

She’s tidy only in spurts. Cleo keeps her dresser drawers neat. She hangs up her own clothes, though she may not get around to it till later. Mostly she goes hatless but never gloveless. Gloves in pastel shades are a small mania with Susan. She collects them as others collect gems. “I must have read somewhere that you’re not a lady unless you own twelve-button kidskins. My gloves are all short,” she adds modestly, “so I’m just half a lady.”

Her jewels consist of one diamond ring and one pair of diamond earrings, the gift of Jess. On her last birthday he gave her, by request, a gold pin designed from her initials. “I like that,” Greg told Dick Dickerman, the designer, “but I’m going to buy my mother a diamond necklace. A big one in the middle and small ones round the rest of her neck. Some other time, though. Right now we’re buying her a birthday cake, I and my brother.”

Susan values the tribute and expects to get along fine without the necklace. You’ll sometimes find her in the backroom at Winsten’s, dripping pearls and emeralds and wine-dark rubies through her fingers for sheer joy in their beauty, knowing she’ll never be able to afford them and content in that knowledge. She never did think that a gal’s best friends are diamonds. Her greatest extravagance is a mink coat. Three years ago, they’d put enough money by to furnish the living room. Came a chance to acquire this coat, ordered by a woman in San Francisco who then got cold feet. “Buy the coat,” said Jess. “I like a nice bare living room where we can stick a projector and show pictures.”

She let him twist her arm. Reveling in the coat, she also points out its utilitarian aspects. “A cloth coat keeps you just as warm, but if you have to go to the hockshop, you get more for the mink.” No hockshop shadows the foreseeable future. Susan, however, has a long eye both forward and back. “I’ve been there before. Who am I to say it can never happen again?”

She likes swimming, seafood and cakes from Ebinger’s bakery in Brooklyn. As a child, she was always allowed to choose her own birthday cake at Ebinger’s. It cost sixty cents then. The price has gone up, and the quality remains up. Whenever she goes east, she never fails to buy pastry at Ebinger’s. She likes dictionaries and encyclopedias. Hers get a big workout, since she’s thirsty for knowledge and intelligent in seeking it. After buying a Toulouse-Lautrec print, she dug up every available book on the artist so she could understand the picture better.

She dislikes the odor of perfume at dinner. For her money it shouldn’t be used until after 8:30 P.M. In deference to this idiosyncrasy, her friends arrive perfumeless to dine. Susan’s a little rueful about the whole thing. “I suppose if I were a nice person, I’d never mention it. But Indiscreet with the roast ruins my appetite.”

She’s afraid of high places. Looking through the window of a New York skyscraper, she’ll make an instinctive grab at something for support. Yet, she’s debonair about flying. Her only reservation involves the children. To protect them, she and Jess have agreed never to make a long flight on the same plane. She’s not exactly superstitious, but doesn’t feel right before starting a picture unless (1) she’s in bed by nine, (2) Jess gives her a red apple, (3) she tunes in the car radio on her way to work and, whatever song’s playing, lets it play on to the end.

She never hopes to sit on a piano and sing in a night club, but thinks it would be awfully nice if she could. The role she most enjoyed was that of Jane Froman, because of its range and the joy of working with so remarkable a woman. No gusher Susan, her eyes light up at mention of Froman’s name. Indirectly, the picture provided another thrill. Prospect Heights High, her alma mater, had long been urging a visit. It was arranged for last March when she went to New York. As the car stopped in front of the building, her pulse pounded. Girls in bright blouses stood lined up outside. The cop remembered her. She recognized the janitor’s beaming face. Teachers of her childhood came forward to greet her. In the art department they showed her the label on the back of all designs—Susan’s winning label, entered in competition with other art students and still used by the school.

The sense of things past worked hob with her emotions. But the climax lay ahead. As she stepped into the auditorium, 4500 fresh young voices rose in welcome. The welcome was set to music and the song was the title song from her greatest success, “With a Song in My Heart.”

Throat knotted, knees melting, she still doesn’t know how she made it to the platform. The principal’s introduction gave her time to pull herself together. In the yearbook just issued, featuring alumnae who’d scored in various fields, Susan was listed as a member of the school’s Honor Art Society and of the Arista League. These things were mentioned as Susan was introduced. Then she spoke. “It all sounds very nice,” she smiled, “but I’m going to tell you the truth. I never did make Arista.” To make Arista, you’ve got to be voted in by all the kids. Shy, introspective, definitely no mixer, she was not.

The current crop took her in. They liked her candor and simplicity. They liked her humor, as she went on to describe the trials of breaking into filmdom. They forgot the celebrity. Here was a girl who’d dreamed her dreams in this same auditorium and returned to give validity to their own dreams. You could feel a great wave of affection mounting and breaking into plaudits. It moved her deeply. Not the applause, but the sense of identity, the invisible handclasp that drew her close and made her one of them. Of all her memories, this is the one she holds dearest.

Hayward’s never been one to flaunt her heart on her sleeve. An instinctive reserve discourages the over-familiar. People like her at Fox, but they’re not free-and-easy with her. Instead of hobnobbing when a scene’s finished, she goes to her dressing room and plays records. Her own self-analysis sounds lucid, fair and convincing. “I’ve always needed a lot of rest. Till I was sixteen, I napped after school every day. I work hard on the set and conserving my energy helps me to work better. But that’s not the whole story I can be contrary. From the back of somebody’s neck, I’ll decide that I don’t like him and he won’t like me. Sometimes I’m right, sometimes wrong. And I do have a tendency to withdraw. This I was born with. Maybe it’s due to shyness, though I doubt that I’m now what you’d call a shy person. Circumstances have forced me to be otherwise. Still, there are times when I clam up like Greg, and I think it’s a failing. It keeps me from giving what I should in friendliness. I find if I make an extra effort, I can overcome it, but it does take that little extra effort. You can’t be best friends with everyone—that’s silly. It’s equally silly to pull into your shell.”

She thinks she’s living the ideal life right now. But for a really terrific imaginary life, she’d take a huge ranch with rolling hills and a stable of beautiful horses, where she and Jess could raise cattle, grow wheat and alfalfa, own a little plane, pick up the twins at will, hop off to Europe or Africa, come back to the ranch and find some new little colts and calves to coddle. Why this of all visions should attract a Brooklynite she can’t explain, unless it’s because she’s seen too many westerns. Would she miss acting? A gleam shoots from under Miss Hayward’s lashes. “I could take care of that in my private life.”

Her faith is simple. She believes God put her into the world for a purpose, and feels a deep responsibility in fulfilling that purpose. When she was seven, a car ran her down, causing injuries that kept her bedded for six months. One day a suitcase arrived from her Sunday school, bursting with so many gifts that she had a new one to open each morning. Susan never got over this. It planted in her impressionable mind a radiant sense of the wonder of people’s kindness. Nothing that’s happened since has changed her view. She believes in the human race, and in trying to be a worthy member thereof. She believes in the essential goodness of life. She thinks that her own has been crammed with as many blessings as that long-ago suitcase. And she knows that the greatest of them all are Jess, Gregory and Tim.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1952

MichaelFlaph

28 Ocak 2023Also that we would do without your very good phrase

MichaelFlaph

28 Ocak 2023This excellent phrase is necessary just by the way