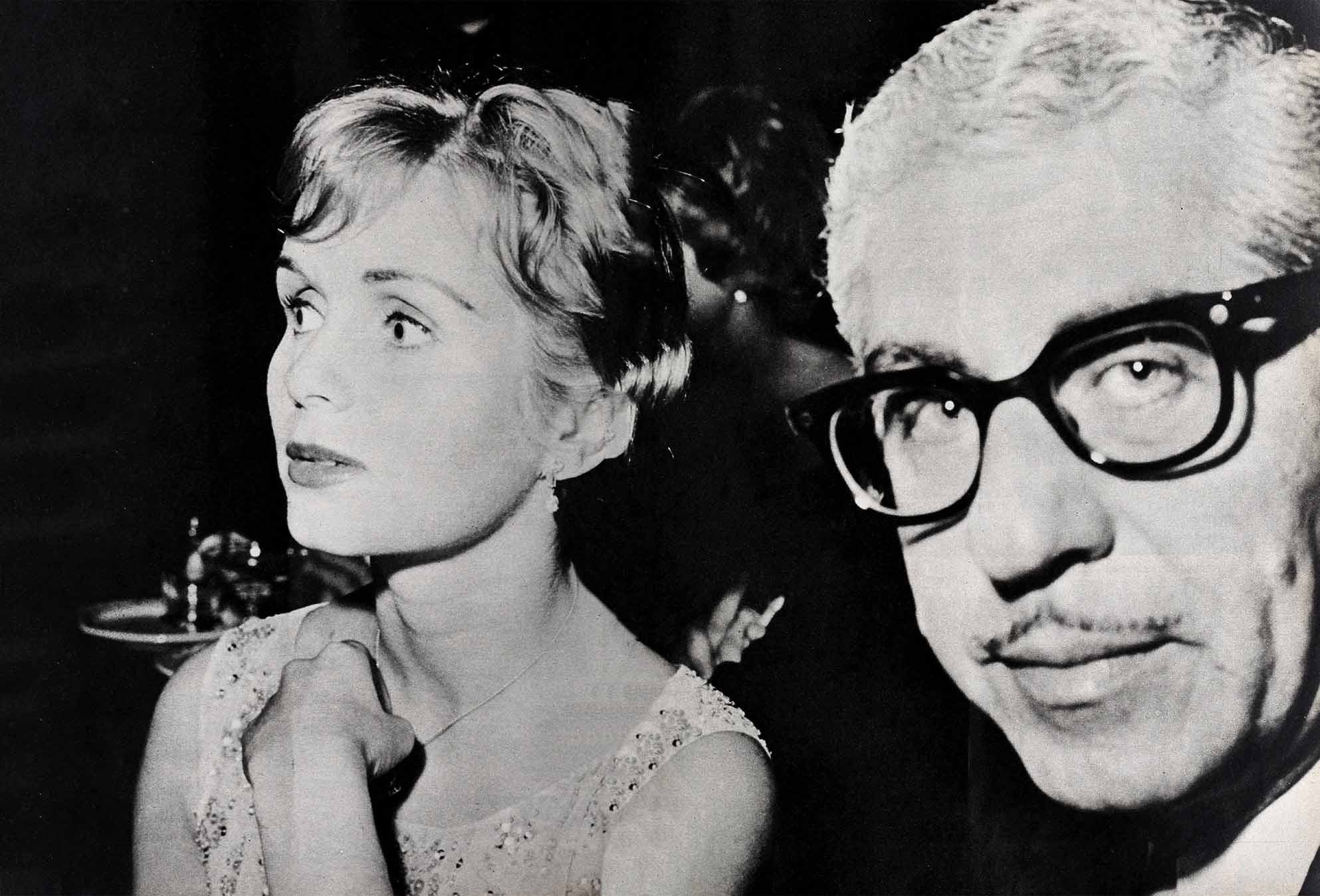

Is Debbie Settling For Less Than Love?

Is Debbie settling for less than love to give her fatherless children a new “daddy”?

“Ooh,” Carrie Frances said. Her wide eyes made round O’s in her small face. “Toddy, look! Isn’t it beautiful?”

Todd Emanuel echoed obediently by nodding his head. Obviously, he couldn’t have cared less. But his big sister had dropped his band now and was wandering over to the heavy stone wall. “bus’ lovely,” she murmured, in perfect imitation of grownup talk. “So pretty. . .”

AUDIO BOOK

Debbie looked around her. Yes, it was pretty. She turned slowly. Very pretty. The beautiful rock wall, the spacious grounds leading to the patio-enclosed swimming pool, the low elegant lines of the house. Inside, she knew it would be even more handsome; though she had never entered the house, she knew of the large airy rooms, the two wood-burning fireplaces, the modern furniture. She knew, because the proud owner of the house had described it to her many times. She knew, because recently acquaintances had made sure that she knew, mentioning casually that, of course, it was a showplace. Oh, not anything extravagant, but if you admired perfect taste, quietly displayed—well, the house was the marvel of Palm Springs.

Of course, it was the house of Harry Karl.

Inside it now, Harry was ordering lunch for them all. For Debbie and her children and her parents, all of whom Harry had driven down to Palm Springs for the weekend. They would be staying, naturally, in Debbie’s own house—the one she had received as part of her divorce settlement from Eddie. “But you mustn’t go straight there,” they had been told as they neared the Springs. “It’s so very unpleasant to go home to an empty house with nobody to meet you.” So when Harry said, “Please come over for lunch. It would give me the greatest pleasure,” they accepted.

Debbie had known it was more than courtesy. It would give him pleasure to have them come. Not simply because he was in love with her—though that was part of it, of course—but Harry would have urged her parents alone, or any casual friend. Sometimes Debbie thought he would—if his shyness let him—do just as much for half a dozen weary tourists, or a trailer-park couple he’d never met before.

“Charity,” he had said once, “is as necessary to life as religion, education—or anything else at all.” But when Harry said “charity,” he used the word in the Biblical sense—translated into “love.” He gave not only money, but himself; he gave not only to the money-poor, but to those who didn’t even know that they were destitute—the poor in heart.

Like me, Debbie thought suddenly. The ones who try to keep busy so they won’t know they’re lonesome. But you can’t keep busy all the time: Sometimes you sit down for a moment and it sneaks up on you—loneliness, emptiness, weariness. And then . . .

Then the phone rings, and it’s Harry Karl, saying, “Let me drive you down to Palm Springs, you and your family. Come on. It will do you good.”

“They need a father”

And all the way down, he jokes and teases the children, starts a discussion that takes your mind off yourself, makes your-parents feel sure they’re not superfluous but an essential part of the outing. And then, with his usual exquisite tact, leaves you alone for a moment in the garden while he orders lunch and shows your folks where they can wash up. How does he know? she wondered. How does he always seem to know when to let me think?

And there was so much thinking to do. With a little sigh. Debbie lowered herself to a stone seat where she could keep an eye on her little ones. Carrie, now exploring the patio, carefully kept away from the edge of the pool. Todd, squatting beside a cactus plant, extended a tentative finger toward a bristle. My babies, she thought proudly. So sturdy and handsome and bright. Enough to fill any heart with love, with joy.

That was what she said, over and over, to reporters, to friends, to anyone who would listen. I have my babies; that’s enough. But so many wanted to argue the point.

“Now. Debbie, mother-love is a wonderful thing. But you’re a woman as well as a mother. A woman is meant to love a a man, too.”

“Now, Debbie, you wouldn’t be depriving the children of something by falling in love again. Did you love them any the less when you loved Eddie? Of course not.”

“Now, Debbie, you know what the psychologists say about over-devoted mothers! You’re so wrapped up in Carrie and Todd; you’ll get possessive and nervous, and that will be terrible for them. Besides, they need a father.”

“But they have a father,” she would protest. “Eddie loves both of them very much.”

“That’s all very nice for Eddie. But where was he when Toddy fell off his tricycle? Where was he during Carrie’s birthday party? Where will he be when Todd wants to learn to drive, and when young men are coming to the house to take Carrie out on a date? A child needs a father who’s there.”

Good friends, tactful friends. They always stopped just short of the obvious, direct conclusion: You’ve got to marry again. You’ve got to make yourself fall in love—or pretend to.

Debbie reached down for a handful of the loose white gravel that covered the “lawn” of the house in the manner of the desert landscaping popular at the Springs. Idly, she let it run through her fingers. Love, she thought.

Everyone gave her so much credit for loving—maybe that’s why they felt she couldn’t be really happy until she married again.

In her twenty-six love-filled years, how many times had she really been in love?

Once! Just once—with Eddie! Half-a-dozen dates with him and she found herself sitting by the phone, willing it to ring; dressing to go out, with her heart doing flip-flops; unable to pass a show-window of a man’s store without thinking, “That would look good on Eddie; Eddie would like that; I wonder if I should buy one of them and send it to Eddie?”

Was it love?

All the things that used to be important to her—her career, her home, the Girl Scouts—all those things began to shrink in size and importance. All the problems that had always kept her from getting serious about a boy now, miraculously, were easy to solve—or forget. A difference in religion? They’d work it out. Careers on opposite ends of the country? They’d commute. Different sets of friends? Everybody’d get to love everybody. Different goals, different desires, different pleasures? They’d each give a little. “Give a little, take a little.” That’s what Eddie’s mother had said on their wedding day, and on that day, of course, it had sounded so easy to do . . .

If everything looked so easy to work out, if you were deeply convinced that a wonderful life, together, was more important than any problem—why, then you knew you were in love.

Yes, she had been in love—once. The fine white pebbles trickled through Debbie’s fingers and made a little heap at her feet.

Debbie’s hand fell open. Her lips parted slightly. She took a deep breath.

Was it possible—was it possible—that, someday, she would believe she had not really loved Eddie either? That she had seen in him a different dream? A dream of a home, children, a deep companionship, a warm world with loneliness shut out? Or had she been in love with the idea of marriage, more than with the man she planned to marry? Girls do that.

Was that love?

A step sounded on the gravel at her side. Debbie looked up. Harry was standing there, smiling down at her, his eyes young beneath the greying brows. “We’ll eat in about twenty minutes. May I sit down?”

“In your own garden?” Debbie said, laughing. “I think it might be arranged.” She moved over on the stone seat. Harry sat down beside her. He moved so easily, she thought for the hundredth time; she noticed his grace and strength automatically. Not a wasted motion. He didn’t bounce around the way a young man would—and, yet, there was nothing weak about him, nothing slow. Merely the movements of a man who has much to do, and knows exactly how much energy and time and motion is required to do it. She knew he liked steam baths, massages. She liked that. She, too, had always believed that decent self-respect required that you take care of your body, keep it clean and fit, keep it a good sight in the eyes of God and man.

And Harry did. His clothes were ex-pensive—not to display wealth, but to fit well and wear well; to let the man inside move easily and forget what he was wearing. They weren’t to admire in front of a mirror or in other people’s eyes. He changed his white shirts as often as three times a day. He took pleasure not in the shirt’s cost, but in its clean, fresh whiteness. Debbie had never yet seen him less than immaculate. Never.

“Debbie?” Harry said. “Debbie? You’re a hundred miles away—”

Debbie looked at him, startled. She was remembering the Desert Rodeo they went to together; she and Harry and the children. “I think I’ll leave you alone with whatever you’re thinking about,” Harry said, standing up. Debbie saw him turn and walk, with long swift strides, toward the pool. She knew she was being rude, but she wanted to be alone to think.

She remembers . . .

For the first time, she yielded to the temptation to close her eyes and recall more vividly what happened on that Saturday afternoon.

They had gone to the Desert Rodeo in the morning, she and Harry and Todd and Carrie. With her eyes closed, she could still see Carrie and Todd in the outfits they had worn that day—the cowboy clothes Harry had given them last Christmas. The children were so excited they could hardly stand still to be dressed. Todd kept jumping up and down, asking, “Mommy, will the real cowboys at the rodeo think that I’m a real cowboy, too?”

Laughing, Debbie assured him they would. Then, Harry came to pick them up in his car.

All through the rodeo, both children pestered him with questions about every-thing they saw—Debbie’s answers didn’t interest them in the least. Harry turned from one child to the other, supplying peanuts, hot dogs, information on why some cowboys had saddles and others didn’t, how far a stage coach would go in one day, how many Indians he had personally killed—until Debbie was torn between laughter and chagrin. It really wasn’t right to inflict two small children on a grown man who wasn’t their father, but Harry was a marvel with them.

The silk handkerchief . . .

After the rodeo, there was a barbecue. Harry led the way, with Todd clinging to his hand. He led them to the corral where the cowboys’ horses could be looked at, past displays of western handicrafts and arts, matching his pace to Todd’s little legs, turning back to Debbie and Carrie with comments and smiles. After a few minutes, Todd stopped and asked for ice cream.

“What?” Harry demanded. “Ice cream before the barbecue? Well, now—you’ll have to ask your mother.”

Todd turned around and, tugging at Debbie’s sleeve, he asked, “Mommy . . . please?” and pointed over to where they were selling the ice cream.

Debbie smiled and shrugged. “They’ve had so much junk already, Harry, I guess an ice cream won’t kill them!”

So Harry waved to a vendor and bought two cones for the children.

“Say ‘thank you,’ Toddy,” Debbie prompted.

Todd grinned up at Harry, his double chocolate cone held firmly in one small. chubby hand. Then, with a howl of perfect bliss, he leaped at Harry and threw both arms around him.

“Todd!” Debbie cried. “Todd—oh, look at the mess you’ve made! Oh, Harry, I’m so sorry. Todd, how could you? Look what you’ve done!”

Todd slipped to the ground and began to wail, half because his mother was cross, half because he had lost most of his ice cream. Harry gazed down at himself and then at the child. “Have you anything like a tissue, Debbie?”

Debbie rummaged frantically in her bag. “No. Oh, darn it. Not a thing.”

“Never mind,” Harry said. “Here—” and from his pants pocket he pulled out an immaculate silk handkerchief.

“Oh,” Debbie said. “That’s good. Give it to me, Harry, and I’ll wipe you off . . .”

Then she had stopped. For, instead of attacking the mess on himself, Harry had stooped down in the dust and pulled Todd toward him. “Don’t cry, little man,” Debbie heard him say gently. “It’s all right. There. Isn’t that better?” And with his white handkerchief he gently wiped Todd’s tear-and-chocolate smeared face, dusted off the cowboy shirt, rubbed at a streak of chocolate on the buckskin shorts. Only when Todd was presentable again and all smiles, with another cone in his hand—then Harry used the silk handkerchief to pat himself dry.

And suddenly, other scenes crowded into her mind. The other, the many times, when Harry had given what he’d never promised.

There was Harry, on their first date, handing Debbie a ten-thousand-dollar check for The Thalians, her pet cause. Not a word about giving a little now, maybe more later if he liked their work. Just then and there—a large check.

And Harry sending her a little golf cart to scoot around the studio grounds instead of walking between sets. Not a word about “My girl shouldn’t wear herself out—you are my girl, aren’t you?” Just the cart, arriving with a note that said he wanted to give her something useful.

And Harry listening to her say, as she’d said to so many other men, “I can’t go on a date before nine, when the children are in bed.” Not a word about nine o’clock being too late for the theater. Not a hint that she was carrying motherly love a little too far. All he asked was could he possibly come over at eight, and help her give them supper?

And Harry driving her all over when she was apartment-hunting for her brother Bill and his bride. Not a word in advance about being willing to do anything, no matter how unpleasant and tiring, for Debbie. He just showed up in his car in front of her house, saying cheerfully, “I just thought that you might like company.”

Could she love again?

Best of all, there was Harry last Christmas in Palm Springs, making no promises to the children as many people did—promises designed to win their affection when Debbie was around and forgotten when she was away. He came with a picnic basket for Debbie to fill with sandwiches and potato salad, and he’d mapped out an itinerary of Indian camps to visit, orchards to see, and palm tree groves to eat in.

It was very strange, indeed, how Harry Karl made no promises—and still fulfilled so much. Strange, how the sound of his voice was so sure, so reassuring.

So many people, in so many ways, had been asking her about Harry Karl:

“Debbie—do you think you could love again?”

“Surely, you don’t mind an older man, do you, Debbie? Look at Doris Day and Jean Simmons and—well, even Liz and Mike Todd! Sometimes, after a girl has had a hard time from a younger man, she finds that someone more mature is just right. Now, you take Harry—and anyway, he’s only forty-seven.”

“Debbie—don’t you think it’s possible for a girl to be in love with a man and not know it? Now take you . . .”

In her heart, she knew she couldn’t listen to what others were saying. She had to make up her own mind.

And today, here in Harry’s garden, she sat and wondered. Love could be many things. A promise. (But promises could be broken.) A dream. (But dreams some-times turned into nightmares.) Love for her had always seemed based on the future—the life they would have together, the joy they would know. Later, always later. For Debbie, love meant you overlooked present problems in hope of future solutions. Love was forgiving today’s quarrel because there would be a reconciliation tomorrow. The future, promises.

From around the house, Harry appeared. Carrie sat perched on his shoulder. Todd strutted like a lord at his side.

“Debbie,” Harry said, “lunch is ready.”

Ah, Harry, she thought, could love come without stars bursting and suns exploding? Could love be gentle and honest and deep and quiet instead? Could it belong to this moment, built on what one knows of a man as he is—not dreams and hopes and prayers that he’ll turn out?

She knew she could never marry without love, not even for Carrie’s and Todd’s happiness. But what if love wore this other face that she’d known too little—the face of goodness and kindness so endearing that you cannot help but love it?

Debbie stood up. Harry was holding out his hand—asking for nothing, except that she come into the house where her parents and children were waiting to sit around the lunch table with their host.

Debbie took Harry’s hand.

“I’m coming,” she said.

THE END

SEE DEBBIE IN PAR ‘S “THE RAT RACE” AND “PLEASURE OF HIS COMPANY.” DON’T MISS HER SPECIALS ON ABC-TV. HEAR HER SING ON DOT. AND WATCH FOR HER IN “PEPE” FOR COLUMBIA.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1960

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments