Phyllis? Phyllis Who?—Rock Hudson

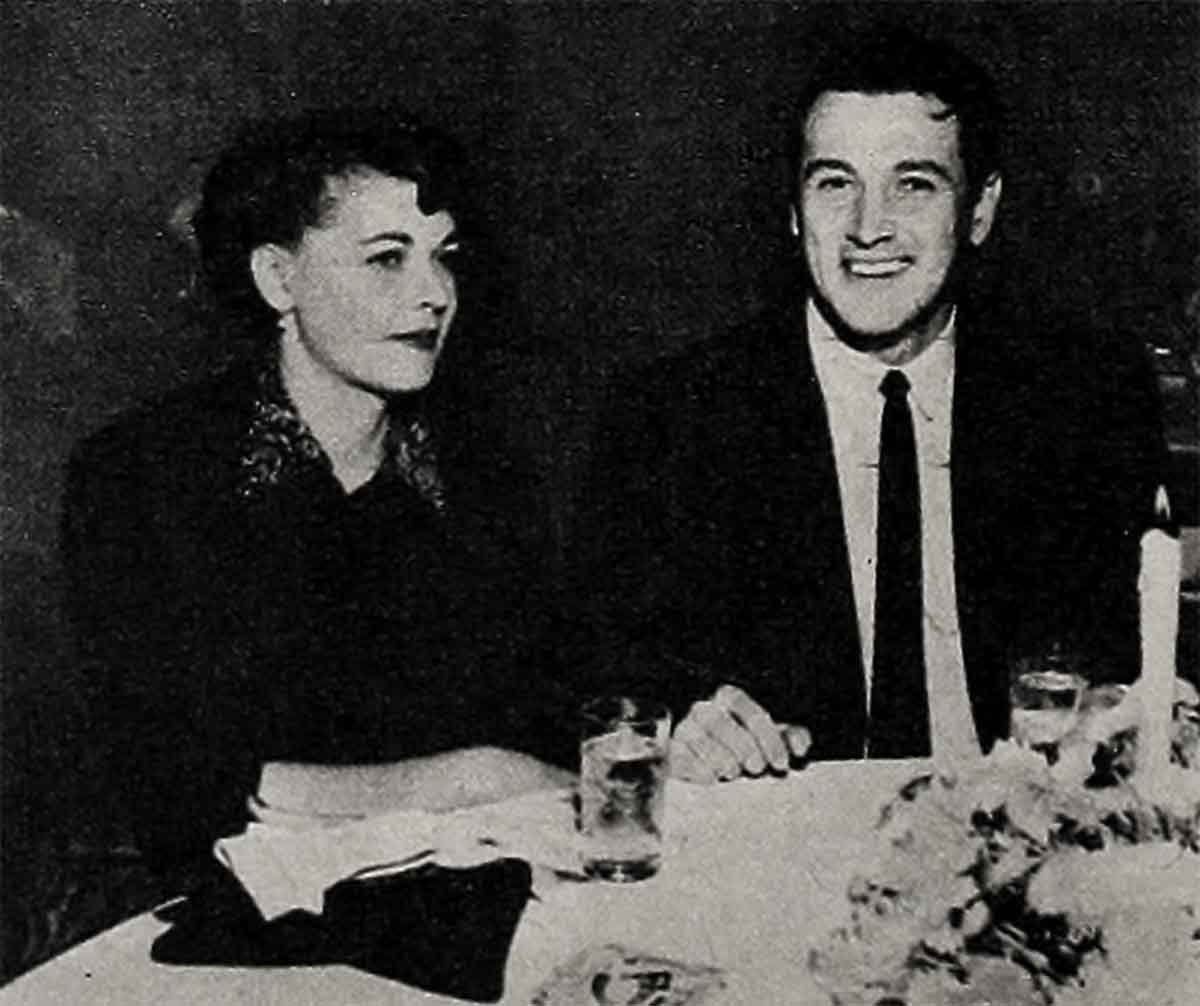

Well sir, there I was again. Confronting Rock Hudson across a white tablecloth, and filled with despair. Not that it’s bad, being confronted with six feet, four inches of all that. You can’t hardly get them kind no more.

He had come to the restaurant straight from his role of gardener in All That Heaven Allows. He wore a sad sport shirt, a used suede jacket and tired denim trousers. The make-up department had tried to make him look dirty, but one of the nice things about Rock is that he can’t look dirty.

The reason for my doldrums was that I had to come up with considerable information about Rock’s latest and greatest date, Phyllis Gates. All Hollywood knows Rock is squiring Miss Gates, and all Hollywood also knows Rock prefers not to talk about it. And so all Hollywood is trying to find out about it.

There is the rub. A nicer guy you can’t find, but he holds as how his own business is his own business, and there’s no business like trying to pry it out of him.

“Well,” he said, “what do you want to talk about this time?” Then he gave me an evil grin and added, “As if I didn’t know.”

I skirted the issue temporarily. “There’s always Christmas and Thanksgiving. What did you do Thanksgiving?”

“Went over to my mother’s.”

When Rock makes a statement during an interview, the period at the end of his sentence looms larger than the moon. It is as if he had just closed the whole interview.

“What did you do on Christmas?”

He smiled engagingly. “I went over to my mother’s.”

I wondered why everybody likes him so much. I wondered why I like him so much. I sighed. “All right, what did you do Christmas Eve?”

“I went over to my father’s.”

“Did anybody ever tell you you’re great copy? What did you do New Year’s Eve? Don’t tell me you spent New Year’s Eve with your family!”

He looked at the ceiling, thinking. “Went to two—no three—parties. Got home at three A.M.”

That about took care of the holidays. Except for one. “Valentine’s Day?” I ventured. “Is there any statement you’d care to make about Phyllis?”

“Phyllis?” he said vaguely. “Phyllis who?”

“Phyllis who, Phyllis who,” I said, Benny style.

He laughed then and I felt sorry for him. We have spent many hours over assorted tablecloths, sparring with each other. For years I’ve been trying to find out what he’s like and have gathered the distinct impression that I never will, but the situation is eased by the fact that Rock does his best, in his inimitable way, to help me. We have fun. You might even say he trusts me. Which makes my work tough.

The fish bowl existence of a film star is not for Rock Hudson. He views his work seriously, more seriously than most, but he has the understandable wish to keep himself to himself. He will tell you what he eats for breakfast, but he will not tell you what he thinks while he’s eating breakfast. If he feels so strongly about such everyday things, it is conceivable that he is unwilling to exhibit the things that are closest to his heart. Phyllis Gates may possibly be one of these things. I had no intention of asking him, partly because I knew he wouldn’t answer, mostly because it’s no fun to needle somebody you like.

The reason for his reticence is quite obvious. His late romance with Betty Abbott is a thing of the past, very possibly because of too much publicity. A man can’t court a girl, and make up his mind while he’s courting her whether or not he wants to marry her, when the press is devoting long paragraphs to the pros and cons of the situation. If he should decide he doesn’t want to marry her, it’s a rather good bet by that time the girl will have believed the publicity and figured he ought to. Currently, Betty Abbott is dating Jeff Chandler and would seem to be quite happy about the whole thing.

With Phyllis, he is in the same potential danger. And understanding this—well sir, there I was.

“Gates,” I said. “Her name is Gates. Now look, I’m not going to ask any impertinent questions, but at this point I can’t very well ignore the subject. I’m supposed to be a reporter.”

“Ha” said Rock. “You’re using psychology on me.”

“Some psychology,” I said. “I’m not hinting—I’m telling you. I won’t ask about your intentions, but I think I might be able to say something about this girl. What does she look like?”

“Well, she has two eyes, two ears, two legs, two arms and a body.” On this last, his eyebrows raised ever so slightly.

“I understand she does,” I said. “She goes to a doctor here in town and whenever she leaves, he makes large wolf noises. ”

Rock looked delighted. “He does, huh? How’d you find that out?”

“I’m a reporter, bub,” I said. “I knew you wouldn’t tell me anything.”

“Doctor who?” he persisted.

“Doctor who, Doctor who,” I said again. “Now tell me, if you can bring yourself to it, are you and Phyllis soul mates? I mean, can you share things with each other, things like humor, a well-turned phrase, a sunset?”

He nodded cautiously. After all, if he told me anything about her, he’d be obliged to tell everybody else in town.

“I understand you’re teaching her to love music,” I said. “How is she coming along?”

He laid down his fork and looked at me aghast. “How’d you find that out?” he said.

“Never mind,” I said. “What’s her favorite at this point?”

“Brahms’ First,” he said before he could catch himself.

“Have a care,” I said. “You’re growing Loquacious.”

We talked about the house then. He bought it in January and he admitted that the house, at least, was love at first sight. It is situated in the Hollywood Hills, is of Pennsylvania Dutch architecture, barn-red with white trim, contains 1350 feet of solid construction. There are two bedrooms, the larger of which looks out on the patio, and the living room has a view of pine trees.

“Real pine trees,” said Rock, and his i is believable to a transplanted Californian who is up to here with palm trees. “There’s a brick walk to the patio, and there are pine needles all over it.”

“Spring-y under your feet?” I inquired.

“Uh-huh. And one day I said to a carpenter who was there working on something, ‘What kind of floors are these?’ And he looked, and he looked again, and he said, ‘I can’t believe it, but it’s teakwood!’ Imagine, real teakwood floors!”

There’s nothing in the house but clothes, records and a borrowed seven-foot bed. His own eight-foot bed will be moved in as soon as possible. This is the end of a two-year search for a house, and Rock is as hysterical about it as a ten-year-old with his first electric train.

“Does Phyllis like the house?” I said.

“She likes houses,” he evaded.

“What is she like?” I said, and when I saw he was bogging down, I helped. “She’s a bubbling sort of a girl, a lot of happiness, but very solid in character. I believe radiant is the word for her personality.”

“Say,” he said. “Do you know Phyllis?”

“No, I don’t. I’m just a reporter.”

He leaned forward. “I’ll tell you something else.” It was as though he was afraid somebody would hear him. “She has confused eyelashes.”

“You mean every which way?” I said, and he nodded.

“How long have you known her?” I said.

“About a year and a half.”

“And your first date was in October?”

“How’d you know that?” he said.

“You told me, on our last interview,” I said. “You took her to Ciro’s and when the photographers crowded around, Phyllis was as excited as a kid. Don’t you remember, you told me she got such a bang out of it that she posed like a real ham and forgot all about you?”

He grinned. “That’s right.”

“I guess I got in on the ground floor before you decided to clam up,” I said. “Anyway, you certainly took your time about asking her for the first date. Cautious, aren’t you?”

“Yup,” he said. “Cautious.”

I asked him if he’d heard what Conrad Nagel said about him. Nagel had joined the cast of All That Heaven Allows, his first Hollywood stint in seven years, and he’d said some pretty nice things about the young Mr. Hudson. Rock hadn’t heard it. As a veteran craftsman of the theatre arts, Nagel had been asked his opinion of Hollywood’s new crop. He said he didn’t think much of them, specifically because they didn’t take their work seriously enough. He said they get star complexes too fast and they even object to working overtime. Did he hold out hope for any of them? only four and Rock Hudson was among them. I told Rock this and waited for his reaction. It didn’t come, so I continued.

“He said you remind him of Gable when the was ing his start, that you have the same attitude toward your work and a great deal of the same appeal.”

Rock didn’t say anything. When you throw a compliment at this boy you get the feeling it isn’t being absorbed. In fact, you can almost hear it bounce off.

“Nagel says you are rare in that everybody at the studio likes you. All the grips—everybody. They say you get nicer all the time.”

Rock buttered a roll. I began to get desperate, felt I had to convince him. “He says you think all the time, that you use your head, particularly that you really think while you’re in front of the cameras.”

Rock cut a slice of corned beef. “Nagel was doing a goodness,” he said.

I gave up. “I suppose you’ll stick with acting. Have you any plans for the future, like buying a farm?”

“It’s not for me,” he said. “I have no desire to go back to the soil. I was there once, on my grandparents’ farm. One day I helped to deliver a calf, and I didn’t enjoy it very much. Tell you what. I have two plans, both of them impossible. One is to own that Chateau Marmont on Sunset Boulevard and live in the penthouse. I’d get my own plane and a license and a place in Palm Springs and a beat-up car. When I wasn’t working I’d fly to the desert and use the jalopy while I was there. Pretty silly, huh?”

“Why is it silly?”

“Because the Chateau Marmont probably costs forty million dollars, that’s why. The other plan would be to own a yacht. I’d work very hard for a year, make maybe six pictures, and then take a year off. I’d sail the yacht through the Pacific, see the islands and Burma and the Red Sea, the Suez Canal and leave the boat docked somewhere in the Mediterranean. Then I’d work a year and then take the boat back the way I came. Alternate, you see, and eventually take in the whole world.” He smiled. “Think of all the shrunken heads I could get for my house.”

“In Pennsylvania Dutch?” I said, horrified.

“Why not?” he said.

“I’ve already got a mother-of-pearl jew’s-harp. I like to collect interesting things.”

“I can see you do,” I said. “Well, I wish you the time to do it all. You’ve been pretty busy. I know you worked in One Desire all through the holidays. How’d you get your Christmas shopping done?”

“They rearranged the schedule, so. I could have a day off.”

“One day? You did all your shopping in one day? But just the things you got for Phyllis alone would have taken a whole day or more.”

He put down his fork again. “What?”

“The cashmere coat,” I said. “And the sweaters and the solid gold necklace. And the fountain pen.”

He lost all interest in his dinner. “Now, how did you know that?”

I smiled back. “Can’t tell.”

“Come on,” he wheedled. “Who told you? Who?”

“The press cannot reveal its source of information,” I intoned. “Do you and Phyllis agree on politics?”

He ignored the question. “How did you find that out?”

“Politics,” I reminded him.

“I don’t know what she thinks,” he said. “Me, I’m not a party-liner.”

“Where do you go when you have a date with her?”

“Around,” he said.

“Do you and Phyllis have the same religious faith?”

“Never asked her,” he said, and then he looked at me. “I suppose this story’s going to be about Phyllis.”

“Now, what ever gave you that idea?”

“We both sang in a choir,” he offered.

“Thank you,” I said. “Have you gone out with anybody else? Publicity dates at premiéres or anything?”

He grinned. “Nobody asks me.”

Then I took him back to the subject of the house. After all, he’d had a hard day at the studio and was hopeful of digesting his dinner. It seems that his main problem is to capture time for shopping. He expects to have two weeks between the finish of All That Heaven Allows and the start of Giant for Warner Brothers. That two weeks, as usual, will be disintegrated by interviews, still pictures, and the myriad chores that follow the finish of a film, but in that time he hopes to buy at least a few things. The décor bothers him. He toys with the idea of Old English, but he isn’t too sure. “I saw six dining tables last week and I liked every one of them.”

“Could Phyllis help you with the shopping?” I said.

He picked up a table knife and pointed it at me and said, “One was oak and round. Do you like round dining tables?”

“They give you trouble in the linen department,” I said. “How do you intend to keep the place clean? Are you planning to leave the bourgeois bin and get yourself a houseman in a white coat?”

“I’ll still have Truitt,” he said.

“Truitt?”

“Sure. Good old Truitt. Haven’t you ever heard about Truitt’ll-do-it? She’s been helping me for a long time, wherever I’ve lived.”

I bent over my notebook, pencil poised. “Two T’s?” I inquired.

He laughed. “Three T’s.”

“Thanks,” I said. “You’re always right there with information I don’t need.”

And the worst of it is, he couldn’t be more charming. We spent two hours over corned beef, cabbage and coffee, and while it was a delightful shank of an evening, I gathered from him only three facts about Phyllis. That she sang in a choir once, that she likes Brahms’ First Symphony and that she has confused eyelashes.

On the way out to the parking lot, Rock disappeared into a phone booth. I passed the booth like I was minding my own business and hadn’t even noticed him in there, hunched up like a Great Dane inside a poodle pen.

The attendant had Rock’s car ready, the motor running.

“Are you with Mr. Hudson?” he asked.

“No, worse luck. I’m driving that convertible with the brown sidewall tires.”

“He sure is a nice guy,” said the attendant. “Not like most of them I see around here. Doesn’t try to make an impression. He’s so easy-going: and quiet.”

Quiet, I told myself, is not the word for it. Thank heaven I knew that girl who knew that man who knew that girl who knew Phyllis. I had arrived with a new notebook and was leaving with one written word—Truitt, with three T’s.

THE END

—BY JANE WILKIE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1955