The Little Girl With The Big Urge

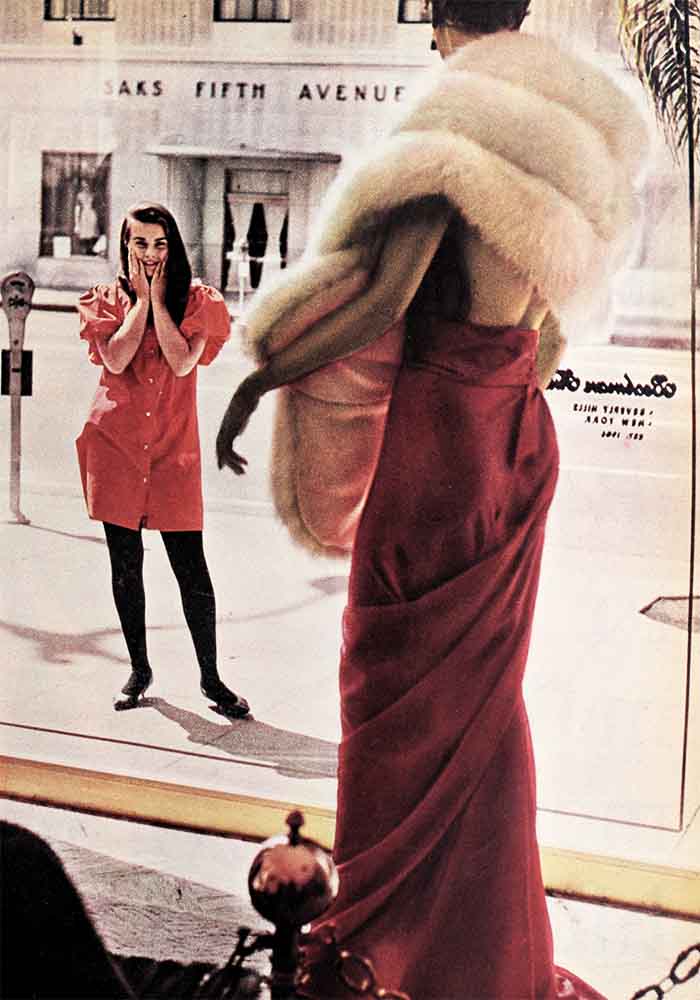

The story did not really begin that night at the plush Beverly Hills party. It began a long way back—before she’d ever seen the inside of such a fabulous house. Tall French windows throwing splashes of light on wide front steps; a butler at the door who led her past a room filled with gay voices—assured, laughing; the blur of satins, diamonds catching rainbows at women’s soft throats and lacquered nails flashing; twinkling of glasses on trays.

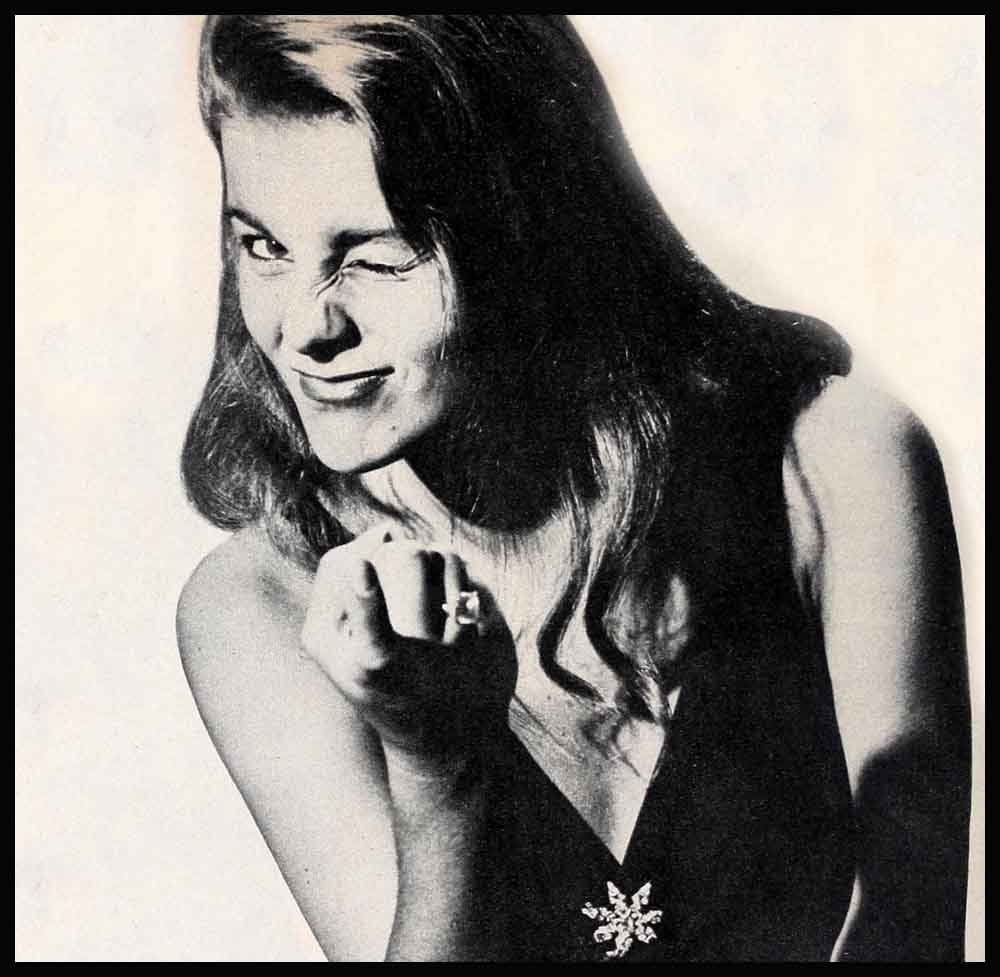

In a little powder room she changed swiftly from a simple cotton dress to velvety black tights and a figure-molding, flame-colored cashmere sweater. She combed her waist-length black hair loose over one cheek, pushed it back over the other shoulder.

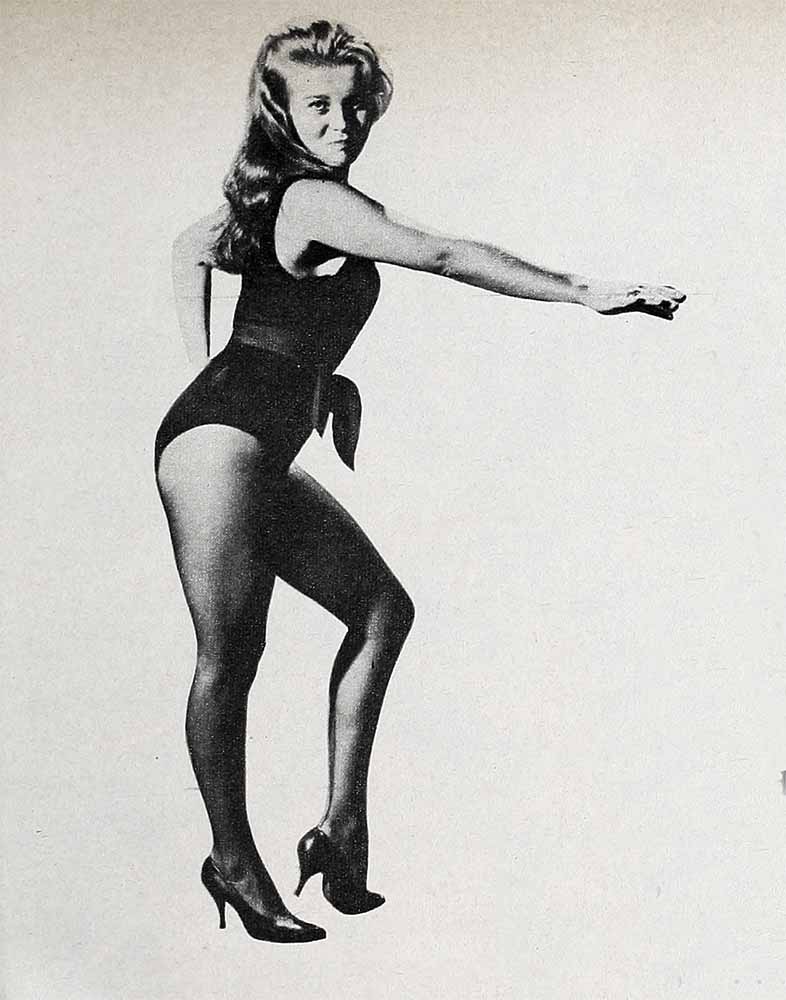

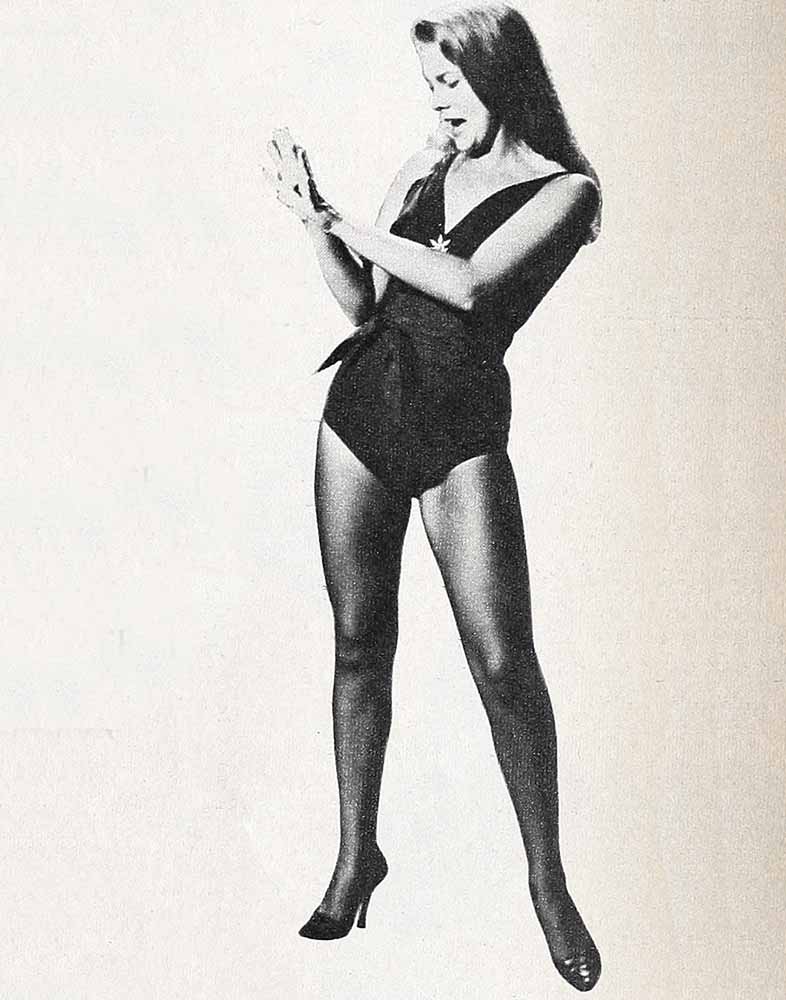

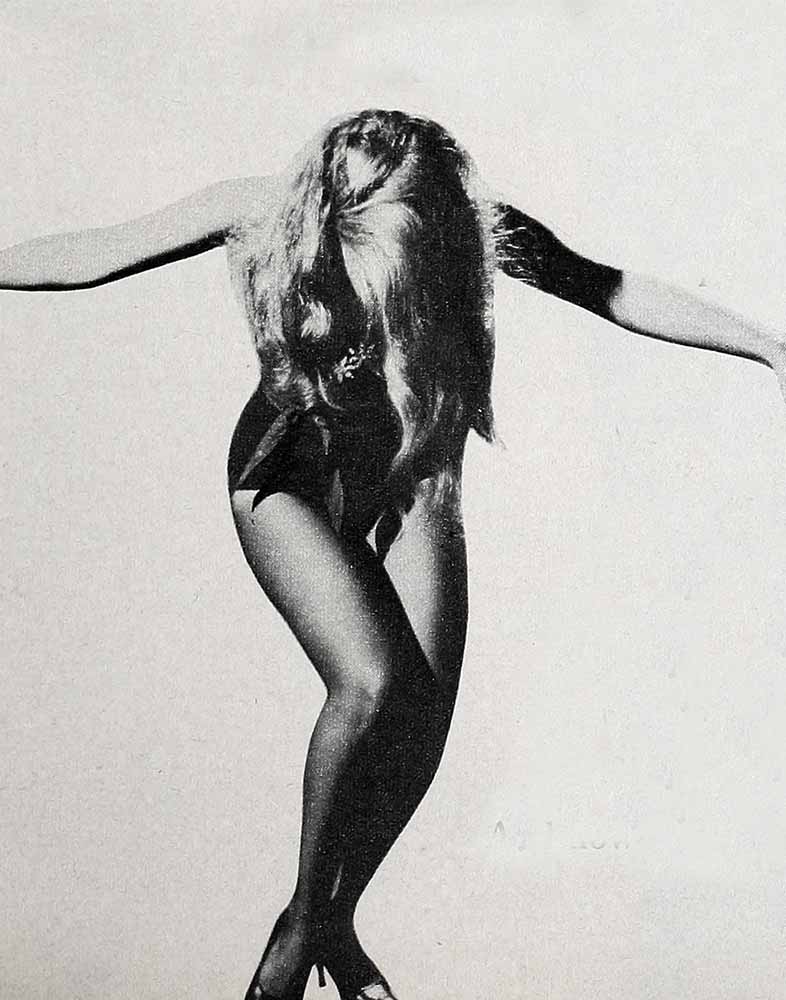

The next minute she was poised before the glittering crowd like a graceful midnight kitten; hearing the piano introduce her with a deep blue note, the bass moving in with a soft lush beat. Then her voice, kitteny-warm and low . . . her body moving the way the music told it to.

The crowd closed in around her. At the end, applause crackled—like dry brush on fire. Most of the faces were friendly, smiling. A few of the men, as usual, clapped too loudly. A few of the women didn’t clap at all. They just looked at her with cold, hard eyes. . . . At 2 A.M., when the old blue Ford clanked out of the long driveway, the girl leaned back in the front seat between the piano player, who was driving, and the bass man. She closed her eyes and told herself, “So . . . this is what it’s all about.” Hollywood . . . like any other place. Las Vegas . . . the applause had the same sound. And the unsmiling ones had the same look. Chicago . . . she knew what they were thinking, the ones who eyed, disapprovingly, the tights that clung like velvet skin.

And now Hollywood. The dream of her life. But while she was still only a few blocks from the sophisticated party and the glittering crowd, she knew what t hey were thinking. Just the same as folks back home in Wilmette, Illinois. . . .

You wait four years . . .

It was spring. 1958. She sat in a closetsized dressing room equipped with one hare light bulb.

For four years she had waited for this night. She had started in the chorus, and a year later been given a few lines, and then a few more lines. Now, four years later, she had her own act!

It was just the annual talent show at Wilmette High School. but to Ann-Margret Olsson it was the test of her life.

Everybody in the audience remembered how she had come from Sweden, at the age of four. with her parents. How she’d started school without knowing a word of English. And now that she was seventeen, beautiful, with long black hair and warm green eyes, she wanted to sing and dance more than anything in the world. This everybody knew. The boys who took her out and wanted to get serious, knew it. Her parents, who had struggled to make a good life for their only child, knew it. Her teachers, friends, everyone who knew anything at all about the popular little Olsson girl, sensed that she would leave Wilmette some day and never return.

But this night, Ann-Margret sat listening to the rest of the cast racing around in last-minute backstage frenzy.

“Ann-Margret”—it was one of the high school music teachers who was putting on the show.

“Not yet,” she said in sudden alarm. “I’m—not ready.”

She clenched her fist. Her nails turned white. She was ready. But she was afraid.

Her heart beat faster. She tried not to think. It was too late to think now. She’d made her decision months ago. When they cast the show.

“You can have your own act,” the teachers had told her. “Work in some dancing, too. We’ll save you next to last.”

It was a big honor. The summer before, she’d gone to Kansas City for a month to sing with a hand in a night club. She’d picked up a professional style. She began to know when a song felt right. when the music reached her. And she knew how to respond.

“I think I’ll do something a little different for the school show this year,” she told her parents.

Ann-Margret had always been a good. sensible girl. A little headstrong, maybe. But good. She’d been a good student, too. liked by teachers and classmates. Her parents didn’t question her now.

“I want to surprise everybody,” she told the teachers. They agreed. Of course, she had to explain. When she told them at first. they nodded. Okay. Fine. She did her own choreography, designed her own dress. It was fun. Easy, too. It seemed to work out just right.

One great big surprise

She never even went through the act at dress rehearsal. It was then that one of the teachers hesitated. “You don’t think it needs to he toned down, do you?” He laughed nervously.

“Don’t worry,” she smiled. “There’s nothing to worry about. Besides, if they’re shocked—I’ll take the blame.”

It all seemed so easy. The last two weeks before the show she hummed “Heat Wave,” the song she’d chosen. Night and day she hummed it.

Right up to the night of the show she never had a qualm. And then, five minutes before her cue, she found herself standing paralyzed. In the tiny dressing room they’d given her, she looked at the girl in the mirror. Her face paled. Her heart raced like a drum roll.

How could she have been so bold?

The dress—what would the audience think? All her friends and their parents. Her own parents, too. What if she’d humiliate them for no reason at all except to be different? To dare what nobody else had ever tried to do in a talent show at Wilmette High.

What if they laughed at her? Worse still, what if they simply sat there, cold and silent? What would she do? How could she ever face them again?

As if in a blind dream she wrenched herself away from the mirror, stopped at the door, breathed a tiny prayer in a small, frightened child-voice: “Please, make them like me.”

She walked out past the rest of the cast, past the little gasps of surprise, the low whistles from the boys, the shocked stares of the girls. She reached the stage just as the little combo—three boys on bass, piano and sax who’d been sworn to secrecy—hit the first notes of “Heat Wave.”

She lifted her head high, ran a nervous hand through her long hair and moved out. Her body swayed with the music, her feet whispered over the stage in a slow, provocative, improvised version of a Calypso step she’d seen in the night club last summer.

Slowly, insinuatingly, she reached the center of the stage, out where everyone in all Wilmette, all her friends, all the parents and teachers and even the Principal and his wife could see.

Heat wave and shock wave

She heard the music, and behind it the drum roll of her heart! Then she flung out her arms, faced the audience fully—and for one split second before the first word of the song rose from her body, she felt the shock wave vibrate from her to the faces out front—and back again.

Ann-Margret Olsson stunned her home town that night. What they saw was a slim, softly curved girl in a breath-tight shiny chartreuse dress with a thin strap clinging to one shoulder, a slit from floor to thigh revealing slender, shapely, hare legs.

She began to sing in a slow, lazy voice, her body moving like a lithe cat waking, stretching, feeling its soft limbs come to life in a luxury of abandon.

As the last notes pounded in her ears she could hear—far away it seemed—people shouting, clapping, cheering.

She left the stage, walked straight to her dressing room. trying to breathe in deep gulps, trying to keep from trembling—now that it was over.

Over? Wilmette High never let Ann-Margret forget that night. True, the head of the music department said her act was the most professional he’d ever seen in a high school show. But that didn’t make up for the fact that most of the women teachers disapproved, and some of the girls seemed to withdraw jealously.

When the yearbook came out in June, Ann-Margret felt a pang at the big picture of herself in the chartreuse dress. She had danced the way she felt like dancing. It had been honest, not phony. Most people admired her courage and talent. Some were shocked.

But one thing was certain: It was too late to go back.

Next year, at the University of Chicago, she quit to follow a vague promise of work in Las Vegas with a trio called “The Subtle Tones.” When they got there, the work had vanished. “Sorry,” the agent told them with an indifferent smile, “you know how it is.”

They didn’t know, but they began to find out.

In Los Angeles, a different agent with the same smile gave them the same story.

Mr. and Mrs. Olsson, who had brought their daughter to this country with only the promise of happiness and bright opportunity to give them courage, sent what little money they could spare. They knew what it was to follow a dream.

That weak trickle of money kept the group alive till fall, 1960.

It was then, with a job singing in a Las Vegas club, that the dream came to life. George Burns saw Ann-Margret and asked her to audition.

By January she had signed long-term contracts with RCA-Victor and 20th Century-Fox. In one year she made “Pocketful of Miracles” for U.A., “State Fair” for 20th, cut several records including the single “I Just Don’t Understand” (sales to date: 350,000) and an LP album, “Here She Is.”

What is she like?

Today, the “little Olsson girl” is being called “the female Elvis” in tribute to her dance gyrations. One Hollywood wolf who saw her act, jumped to the wrong conclusions. In his parked car Ann-Margret told him in a level, good-humored voice: “Sorry—you’re talking to the wrong girl.” Ordinarily that’s all a man needs to hear. This Romeo was stubborn. “Please take me home,” she added quietly.

He did. Eventually this same aggressor confided to friends. “You know, she’s really a nice, sweet, sensitive person.” There are other views, of course. Ty Hardin, Gardner McKay, Gary Clarke, Frankie Avalon, Peter Brown have all had reactions, severe to moderate.

Take Peter Brown. He first heard of Ann-Margret in Las Vegas. “Go watch her,” somebody said. And he did. She sang that night wearing a simple brown print cotton dress with puff sleeves. But beautiful no matter what she wore, he had to admit, with those cool, chiseled Scandinavian features and warm green eyes that sizzled in his direction.

Later he invited her over to his table. When she sat down he asked, “What would you like to drink?”

“Seven-Up,” she said firmly.

He looked at her with a long, level glance. She met it with eyes that never wavered. Then they both grinned.

He said, “I’m Peter Brown.”

She said, “What do you do?”

Peter began to blush. He didn’t know exactly why. There was just something about her. He told her about his TV series, “Lawman.” She replied with embarrassment, “Oh. then you’re a famous actor.” But she didn’t pretend to have known about him all along. From then on, they began to like each other. Perhaps because it was clear from the start: There was no pretending with Ann-Margret.

If some men—misled by her openly sensuous dancing and singing style—are disappointed when they meet her in person. she doesn’t seem concerned. The sensational performer in black tights says, “I feel the lyrics of the song. Whatever comes out is what’s inside me. I love to feel a song building in me, and I love to move.” But the reserved, ladylike young woman, who lives with her folks now in a modest Beverly Hills apartment, neither drinks nor smokes. Her family is Lutheran and attends church every Sunday.

So it’s small wonder that she recently confused a group of hard-boiled record distributors. As an RCA spokesman recalls: “Before the show, Ann-Margret sat at the banquet table dressed in a simple cotton dress. Nobody paid much attention to her. When it was time, she left the table quietly and went to change. The next time we saw her, she came out on stage in black tights and red sweater, singing those rock ’n’ roll songs with enough dynamite to blow the roof off the house. After the show, she joined us again in the plain little dress. Most of us didn’t even recognize her at first. We couldn’t see how this sweet little girl could be the same one who out-swiveled Elvis on stage. A company man had to take her arm and say, ‘This is Ann-Margret,’ before it began to sink in. Then you should have seen the stag line form!”

Though top columnists have predicted stardom for the little girl with the big urge, and George Burns calls her his prodigy, and RCA and 20th have invested heavily in her future, she is still a newcomer, no matter how promising. And as such, has to answer some pretty blunt questions, no matter how much they make her wince. One question invariably pops up:

“How can a nice girl move around like that and still be nice?”

What’s a “nice girl”?

She knows she has her critics. A girl who dresses in tights instead of chiffon, swivels around a mike instead of standing still and holding on to it, is bound to make somebody indignant. Fights have already been touched off at parties where she has entertained. But Ann-Margret says. ‘I have to do what’s right for me. I don’t try to oppose convention, but I can’t sing or dance the way I don’t feel just because somebody else mightn’t like it. I have to take a chance—go my way—and pray that people understand.”

As to that, some in Hollywood claim she’s easy to know, others don’t understand her at all. And she says, “I know it’s easy to get to know me a little, but it’s hard to know me a lot.”

A close friend (male) says this: “Ann-Margret is one of the few girls I’ve ever known who can be feminine and still make a man blush.”

But—on further questioning—it turns out that the reasons for blushing aren’t always what you’d think. On a trip to New York she wore a thin gold bracelet every day. When an interviewer asked about it she said, “It’s from John,” indicating a young man representing RCA.

He turned bright pink. “Oh—” he stammered, “it only cost a dollar.”

Ann-Margret shrugged. “It doesn’t matter what it cost. I like it, and that’s why I wear it.”

The young man brightened. “You know,” he confided later, “it’s the first time a girl ever made me feel she really liked something I gave her.”

And a young bell-hop came out of her room red as a beet. He’d gone in for her luggage, and when she heard his broken English, she asked where he was from. Syria, he told her.

“My,” she said, “that must be so far away. I bet you get homesick sometimes.” They chatted. Anyone could see he was going to run straight downstairs and tell his friends about the beautiful girl who talked so nicely to him.

And this, say her close friends, is why Ann-Margret makes men blush. Because they can’t get over such a beautiful girl showing them the least bit of attention, either.

—BARBARA HENDERSON

Ann-Margret’s in “Pocketful of Miracles,” U.A., and “State Fair,” 20th, coming soon.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1962