Marilyn Monroe And The Camera

Even before Norma Jeane Baker changed her name to Marilyn Monroe, she began her passionate and enduring love affair with the camera. In the summer of 1945, while employed in an aircraft factory, she was selected to model for photographs to promote the war effort. The rest, as they say, is history. Her unparalleled relationship with the camera was one in which each partner was equally enamored with the other, and it lasted nearly twenty years.

The full dimensions of that affair are superbly captured here for the first time. An unsurpassed photographic chronicle, Marilyn Monroe and the Camera brings together the most beautiful and unusual Marilyn Monroe photographs available—the early assignments for advertising and pinups, the film and publicity stills, the classic portraits by such notable photographers as Richard Avedon, Philippe Halsman, Cecil Beaton, and Bert Stern, the paparazzi shots from the hordes of photographers who followed her every move. These entrancing images provide a lavish and extraordinary tribute to the life of America’s legendary movie star.

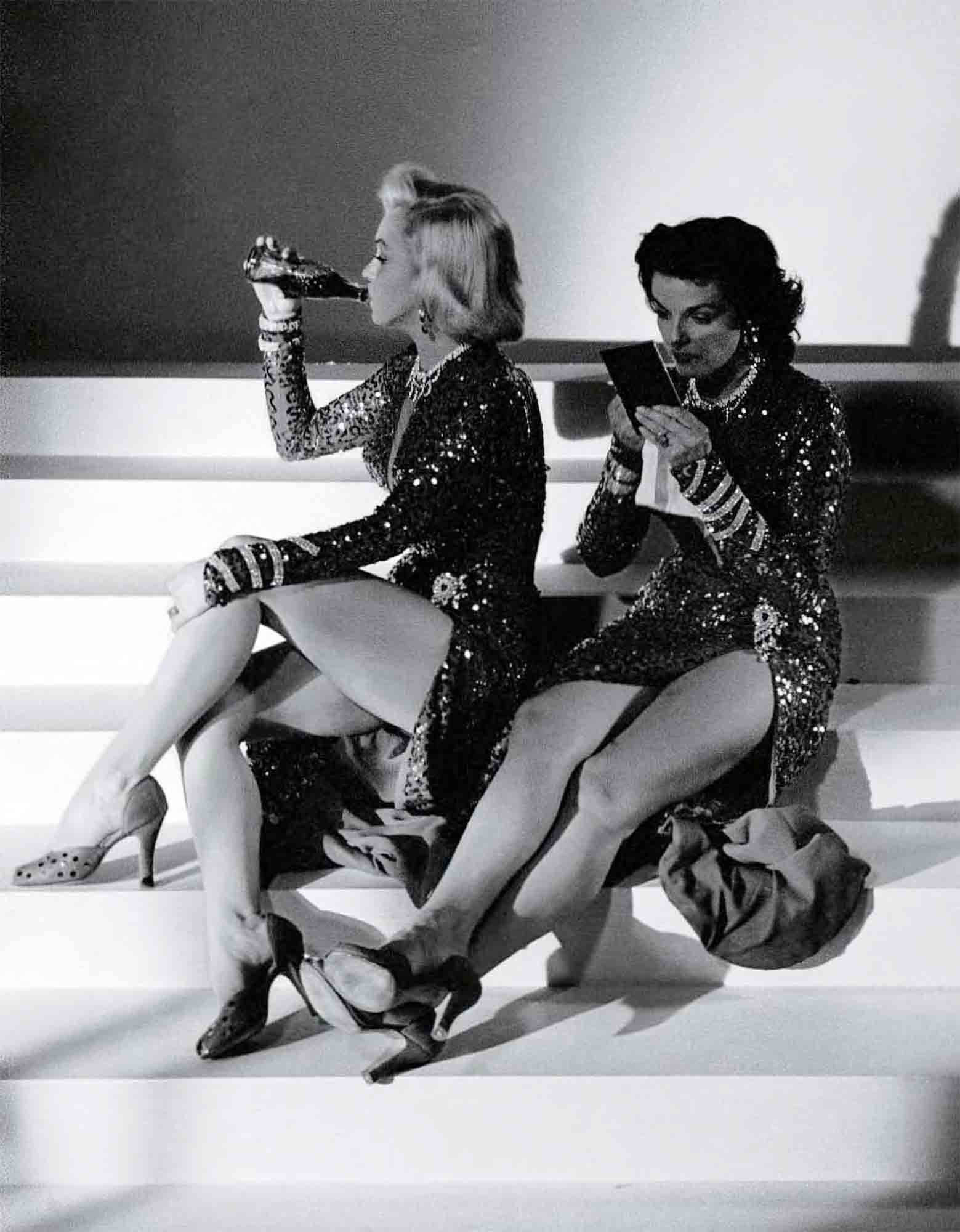

In addition, an interview with Marilyn, conducted in 1960 by the French writer Georges Belmont and never before published in English, provides a fascinating view of the real woman behind the glamorous facade. She describes her lonely childhood, her climb to the top, and the daily workings of her everyday life in a charming, natural, and unguarded manner. Jane Russell, who costarred with her in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, enhances the portrait with an affectionate foreword offering a revealing glimpse of what it was like working on a set with Marilyn. A biography and filmography are included to make this one of the most complete illustrated articles available.

Foreword

The first time I met Marilyn she was dancing with her first husband, Jim Dougherty, a past schoolmate of mine. He was in uniform and called out to me, “Hey, outlaw! I want you to see my wife. Norma Jeane.” I looked up from the table and saw a little thing with ash-brown hair and a very sweet smile. We waved hi. She was curled literally over his arm. A year or so later I was riding with the director Nick Ray on the RKO lot when we passed a girl wearing very “stressed” blue jeans and a man’s shirt tied under her bosom and showing quite a lot of midriff Nick stopped the car and said, “I’d like you to meet this kid. . . . She’s having a tough time on her picture with the lady star, who is being very sarcastic to her.” As she walked alongside, he called, “Marilyn, I want you two to meet. Jane, this is Marilyn Monroe.” Her hair was blonder now—tousled, but definitely blonder.

Nick was very concerned, caring, protective.

I believe that the outstanding quality that made Marilyn different from other so-called sex symbols was her . . . vulnerability. Everyone wanted to take care of her, to help. She brought out protective ness in all but the insensitive, or those who, of course, simply wanted a more sophisticated adult world where everyone was responsible to himself, a world of caustic humor, a take-as-much-as-you-give world. I was accustomed to that world, but Marilyn could get terribly hurt. She simply could not understand people being mean. She was super sensitive—and with good reason, considering her rudderless past and unsure future.

Marilyn had a never-ending thirst for knowledge and self-improvement. She loved poetry and music and was instinctively drawn to culture, to all the arts, but money and power were not to be gained by coercion; especially not when applied to Marilyn. She would flit off like a butterfly. I remember her saying, “If they aren’t going to be fair and nice, I can always leave. I can get by on very little. After all, I’ve done it before.” When we started making Gentlemen Prefer Blondes she was in her very first “star” dressing room, even though she had already starred in a picture. She was determined that her bosses at Fox were going to take her seriously. She worked night and day rehearsing the dance numbers, or she’d shoot the film all day and then go over the script with her coach at night. I’d go home exhausted and ready to relax, but Marilyn worked on into the night. The next day she would arrive a good ho ur before I did. She was always ready but could not make herself get out on the set. She puttered, seemingly frozen there. It got a little tense on the set for a couple of days—you just didn’t keep Howard Hawks waiting without getting the steely blue eye! Whitey, her makeup man, confided to us in my dressing room that he felt that she was afraid to go out on the set—to face the “tiger,” as it were.

So, from then on, I would stop by her dressing room and say, “Come on, Blondel, it’s five of Let’s go get ’em!” Marilyn would look up and in her little-girl whisper say, “Oh . . . O.K.,” and we’d trot out together. We all found her very cooperative, sweet, and humorous, and when the camera rolled she glowed. Physically, she seemed to have no bones . . . she curved every which way . . . undulating flesh . . . and yet, the innocence of a child was ever present. If you raised your voice at her or were too harsh, she’d cry—you knew that.Still photographers are the gentlest of creatures. They coax the very best out of their subjects. They have to, or they’d lose you . . . and our girl Marilyn responded to them like a flower opening to the sun—as you can see in the following pages.

—Jane Russell

Marilyn’s Interview with Georges Belmont

Rupert Allan, who took care of Marilyn Monroe’s publicity, arranged the famous 1960 interview Marilyn gave Georges Belmont, who was then the editor of the French magazine Marie Claire. The interview took place while Let’s Make Love was being shot, a film which of course received everybody’s attention in France because of costar Yves Montand. Georges Belmont soon managed to gain Marilyn s confidence by promising to give her a transcript of the interview and to keep strictly to her actual words when using the text. All those who heard the interview later realized to their surprise that they had never heard Marilyn talk about herself so naturally. Georges Belmont describes the atmosphere: “I just let her go ahead and speak. The only pressure I exerted was silence. When she was silent, I didn’t say anything either, and when she couldn’t stand it any longer and then continued talking she usually said something very important, something very moving.” In view of the photographs in this book, which record Marilyn’s career in all its glamour and glory virtually from the very first to the very last photo, we think it necessary and right that Marilyn herself has a chance to speak in this book.

MM: I’d much rather answer questions. I simply can’t tell the whole story, that’s terrible. . . . Where to begin? How? There are so many twists and turns.

GB: Still, it began somewhere. Your childhood?

MM: Well, that . . . no one knew anything about it, except through pure coincidence. For a long time my past, my life, remained completely unknown. I never spoke about it. No particular reason, but simply because I felt it was my affair and not something for other people. Then one day a Mr. Lester Cowan wanted to put me in a film with Groucho Marx, called Love Happy. At that time I was under contract to Fox and Columbia, although they wanted to drop me. . . . He offered me a small part, this Mr. Cowan; but he was interested in putting me under contract. So he called. I was still very young, and he said he wanted to speak to my father and mother. I told him, “Impossible.” “Why?” he insisted. So I briefly explained the situation: “I never lived with them.” That was the truth, and I still don’t see what was so unusual about it. But then he called Louella Parsons and told her the whole story, and it all appeared in Louella’s column. That’s the way it all began. Since then so many lies have been spread around. . . . My goodness, why shouldn’t I simply tell the truth now?

GB: What are your earliest childhood memories?

MM: [long silence] My earliest memories? . . . It’s the memory of a struggle for survival. I was still very small—a baby in a little bed, yes, and I was struggling for life. But I’d rather not talk about it, if it’s all the same to you. It’s a cruel story, and it’s no one’s business but my own, as I said.

Anyway, as far back as I can remember, I can see myself in a baby carriage, in a long white dress, on the sidewalk of a house where I lived with a family that wasn’t my own.

It’s true that I was illegitimate. But everything that’s been said about my father or my fathers—is wrong. My mother’s first husband was named Baker. Her second was Mortensen. But she’d been divorced from both of them by the time I was born. Some people say my father was Norwegian, probably because of the name Mortensen, and that he was killed in a motorcycle accident right after my birth. I don’t know if that’s true, because he wasn’t related to me. As far as my real father is concerned, I wish you wouldn’t ask . . . but there are a couple of things that could clear up some of the confusion. When I was very young, I was always told that my father was killed in a car crash in New York before I was born. Strangely enough, on my birth certificate under father’s profession there’s the word “baker,” which was the name of my mother’s first husband. When I was born—illegitimate, as I said—my mother had to give me a name. She was just trying to think quickly, I guess, and said “Baker.” Pure coincidence, and then the official’s confusion. . . . At least, I think that’s the way it was.

Anyway, my name was Norma Jeane Baker. It was in all my school records. Everything else that’s been said is crazy.

GB: Your mother. I read somewhere that to you she was just “the woman with the red hair”?

MM: I never lived with my mother. That’s the truth, no matter what some people have said. As far back as I can remember I always lived with other people.

My mother was mentally ill. She’s dead now. And both of her parents died in mental institutions. My mother was also committed. Sometimes she got out, but she always had to go back.

Well, you know how it is. . . . When I was real little, I’d say to every woman I’d see, “Oh, there’s a mommy!” And if I saw a man, I’d say, “Oh, there’s a daddy.” But one morning—I was only about three—I was taking a bath and I said, “Mommy” to the woman who was taking care of me. And she said, “I’m not your mommy. Call me ’Aunt.’“” But he’s my daddy!” I said and I pointed to her husband. “No,” she said, “we’re not your parents. The one who comes here with the red hair, she’s your mother.” It was quite a shock to hear that. But since she didn’t come very much, it’s true that to me she was always “the woman with the red hair.”

Anyway, I knew that she existed. Then later on, when I was in an orphanage, I had another shock. I could read then, and when I saw the word “orphanage” in gold letters on a black background, they had to drag me in. I screamed, “I’m not an orphan! I have a mother!” But then I thought, “I’d better believe she’s dead.” And later people said, “It is better that you forget about your mother.” “But where is she?” I asked. “Don’t think about it,” they said. “She’s dead.”

And then a little bit later I suddenly heard from her. . . . And that’s the way it went for years. I thought she was dead, and I said so, too. But she was alive. So some people accused me of making it up that she was dead because I didn’t want to admit where she was. It’s crazy.

Anyway, I had—let’s see—ten, no, eleven families.

The first one lived in a small town near Los Angeles—I was born in Los Angeles. Along with me they had a little boy they later adopted. I stayed with them until I was around seven. They were terribly strict. They didn’t mean any harm—it was their religion. They brought me up harshly, and correctedme in a way I think they never should have—with a leather strap. That finally came out, and so I was taken away and given to an English couple in Hollywood. They were actors, or I guess I should say extras, with a twenty-year-old daughter who was the spitting image of Madeleine Carroll. Life with them was pretty casual and tumultuous. That was quite a change from the first family, where we weren’t allowed to talk about movies and actors or dance or sing, except maybe for psalms.

My new “parents” worked hard, when they worked, and they enjoyed life the rest of the time. They liked to dance and sing, they drank and played cards, and they had a lot of friends. Because of that religious upbringing I’d had, I was kind of shocked—I thought they were all going to hell. I spent hours praying for them.

I remember something . . . after a few months my mother bought a small house where we were supposed to live. Not for very long maybe three months. Then my mother had to be committed again. And that was a big change. After she left, we moved back to Hollywood.

The English family kept me as long as there was money—my mother’s money from her savings and from an insurance policy she had.

Through them I learned a lot about the movies. I wasn’t even eight. They used to take me to one of the big movie theaters in Hollywood, the Egyptian or Grauman’s Chinese. I used to watch the monkeys in the cages outside the Egyptian, all alone, and I tried to fit my feet into the footprints in front of Grau-man’s, and I could never get my feet in because my shoes were too big. . . . It’s funny to think that my footprints are there now, and that other little girls are trying to do the same thing I did.

They took me there every Saturday and Sunday. That was a break for them, I think; they worked very hard and they didn’t want to be bothered with this child around the house all the time. It was probably better for me, too.

I’d wait till the movie opened and then for ten cents I’d get in and sit in the front row. I watched all kinds of movies there—like Cleopatra with Claudette Colbert; I remember that so well.

I’d sit there and watch the movie over and over. I had to be home before it got dark, hut how was I supposed to know when it was dark? The folks were good to me: even if I didn’t get anything to eat when I was hungry I knew they’d save something for me at home. So I stayed at the movies.

I had favorite stars. Jean Harlow ! I had platinum blonde hair and people used to call me “tow-head.” I hated that and I dreamed of having golden hair . . . until I saw her, so beautiful and with platinum blonde hair like mine.

And Clark Gable. I’m sure he wouldn’t mind if I say it, because in a Freudian sense it’s supposed to be very good . . . I used to think of him as my father. I’d pretend he was my father—I never pretended anyone was my mother, I don’t know why—but I always pretended he was my father. . . . Where was I?

GB: The English couple. And when the money ran out. . . .

MM: Oh, yes. They put me in an orphanage. No, wait a minute. When the English couple couldn’t keep me anymore, I went to stay with some people in North Hollywood, people from New Orleans. I remember that because they always called it “New Orleeens.” I didn’t stay there long, two or three months. I only remember that he was a cameraman and that one day he suddenly took me to the orphanage.

I know a lot of people say that the orphanage wasn’t so bad. But I do know that it’s changed in the meantime. Perhaps it’s not as gloomy. . . . But of course even the most modern orphanage is still an orphanage—if you know what I mean.

At night, when the others were sleeping, I’d sit up in the window and cry because I’d look over and see the RKO studio sign above the roofs in the distance, where my mother had worked as a cutter. When I went there to work, years later, in 1951, doing Clash by Night, I went up to see if I could see the orphanage. But there were too many tall buildings in the way.

I once read, I don’t know where, that there were only three or four of us in a room in the orphanage. That’s not true. I slept in a room with twenty-seven beds, where you could work your way to the “honor” bed, if you behaved. And then you could work yourself into the other dormitory, which had only a few beds. I got to the honor bed once. But one morning I was late and was putting on my shoes when the matron said, “Come downstairs!” I tried to tell her I was tying my shoes, but she said, “Back to the twenty-seventh bed.”

We’d get up at six in the morning, and we did our work before we went to the public school. We each had a bed, a chair, and a locker. Everything had to be very clean, perfect, because of inspection. For a while I cleaned the dormitory where I slept. Every day you moved the beds and you swept and then you dusted. The bathrooms were easier; there was less dust because of the cement floors. And I worked in the kitchen, washing dishes. There were a hundred of us, so I washed a hundred plates and all those spoons and forks. . . . We didn’t have knives or glasses and we drank out of mugs. But in the kitchen you could earn money. We made five cents a month. They took apenny out for Sunday school, so that you had one penny left at the end of the month if there were four Sundays. We’d save that to buy a friend a little thing for Christmas.

I can’t say I was very happy there. I didn’t get along very well with the matrons. But the superintendent was very nice. I remember one day she called me into her office and said, “You have very fine skin, but it’s always so shiny. Let me put a little powder on to see if it helps.” I felt honored. She had a little dog, a Pekinese, who wasn’t allowed to be around the children because he would bite them. But the dog was very friendly to me and I really loved dogs. . . . I was really very honored; I mean, I was walking on air.

Later, I tried to run away with some of the other girls. But where to? We couldn’t decide, we hadn’t the slightest idea. We only got as far as the bump in the front lawn when we were caught. The only thing I said was, “Please don’t tell the superintendent!”—because she’d made me smile and put powder on my nose and let me pet her dog.

In the orphanage I began to stutter. The day they brought me there, after they pulled me in, crying and screaming, suddenly there I was in the large dining room with a hundred kids sitting there eating, at five o’clock, and they were all staring at me. So I stopped crying right away. Maybe that’s a reason along with the rest: my mother and the idea of being an orphan. Anyway, I stuttered. That was the first time. Later on, in my teens, when I was at Van Knight High School, they elected me secretary of the English class, and every time I had to read the minutes I’d say, “Minutes of the last m-m-mmeeting.” It was terrible. That went on for two years, I guess, until I was fifteen.

Sometimes it even happens to me today if I’m very nervous or excited. Once when I had a small part in a movie, in a scene where I was supposed to go up the stairs, I forgot what was happening and the assistant director came and yelled at me, and I was so confused that when I got into the scene I stuttered. Then the director himself came up to me and said, “You don’t stutter.” And I said, “That’s what you think.” It was painful. And it still is if I speak very fast or have to make a speech. Terrible . . . [ silence ].

I stayed about a year and a half in the orphanage. We went to the public school. It’s very had to have children from an institution like that go to a public school because the other kids point their fingers: “Oh, they’re from the home, they’re from the home.” We were all ashamed to be from the orphans’ home.

In school I liked singing and English. I hated arithmetic. I never had my mind on it, you know? I was always dreaming in a window. But I was good at sports.

I was pretty tall. At the orphanage, the first day, they didn’t believe me when I said I was nine years old. They thought I was fourteen. I was almost as tall as I am now—five feet six inches. But I was very, very thin until I was eleven. Then things changed.

Suddenly, I wasn’t in the orphanage anymore. I complained so bitterly to my guardian that she got me out. My guardian Grace McKee. She’d been my mother’s best friend. She died eleven years ago. While she was my legal guardian she worked as a film editor at Columbia. But she was fired, and she married a man ten years younger than herself and he had three children. They were very poor, so they couldn’t care for me. And I think she felt that her responsibility was to her husband, naturally, and to his kids.

But she was always wonderful to me. Without her, who knows where I would have landed! I could have been put in a state orphanage and kept there till I was eighteen. My orphanage was private, and Grace used to visit me and take me out. Not as often as they say, but she used to come and take me out sometimes and I could put on her lipstick. I was only nine then. She’d take me someplace to get my hair curled, which was unheard of because it wasn’t allowed and because I had straight hair. Things like that meant a great deal to me.

Besides, she was the one who got me out of that orphanage after I complained so much, as I said. Of course that meant a new “family.” I remember one where I stayed for just three or four weeks. I remember them because the woman delivered things her husband made. She’d take me along and I’d get so carsick! I don’t know if they were paid for taking me in. I only know that after them I kept changing families. Some took me at the end of the school year and then they had enough after the vacation. But maybe that’s what had been arranged.

Then Los Angeles County took over my support. It was awful. I hated it. Even in the orphanage when I went to school, I tried not to look like an orphan. But now this woman would come around and say, “Now let’s see, I think you need some shoes.” And she would write it down: one pair of shoes. Then, “And does she have a sweater?” Or, “I think the poor girl needs two dresses, one for school and one for Sunday.”

Well, the sweaters were ugly, they were made of cotton, and the clothes all looked like they were made of flour sacks . . . terrible. And the shoes! I’d say,“I don’t want them.” I always tried to get clothes from grown-ups that would be altered for me. And I wore tennis shoes a lot. You could get them for ninety-eight cents.

I must have looked pretty funny then—I was so tall, as I said, and I ate everything. I know because the families I lived with said they’d never seen a child who ate everything. I’d eat anything.

I also know that I was very quiet, at least in front of adults. They used to call me “the mouse.” I didn’t say very much except to other children, and I had a lot of imagination. The other kids liked to play with me because I could think of things. I’d say, “Now we’re going to play murder . . . or divorce.” And they’d say, “How do you think of things like that?”

I was probably a lot different than the others. Kids usually refuse to go to bed, but I never did. Instead, I’d say, “I think I’ll go to bed now.” I loved the privacy of my room, my bed. I especially loved to act out every part of the last movie I’d seen. You know, standing on my bed, being even taller, I’d act out all the parts, the men as well as the women, and I’d work out what happened before or after. It was wonderful. . . . So was acting in school plays. Once I played the part of a king and once the part of a prince—that’s because I was so tall.

I had a real happy time while I was growing up when I went to live with a woman I called “Aunt Anna.” She was Grace McKee’s mother. She was a lot older, she was sixty, I guess, or somewhere around there, but she always talked about when she was a girl of twenty. There was real contact between us because she understood me somehow. She knew what it was like to be young. And I loved her dearly. I used to do the dishes in the evening and I’d always be singing and whistling, and she’d say, “I never heard a child sing so much.” So I did it during that time. Aunt Anna . . . I adored her.

When I was fifteen, turning sixteen, Grace McKee arranged a marriage for me. There’s not much to say about it. She and her husband wanted to move to West Virginia. In Los Angeles the county paid them twenty dollars a month for me. If I’d gone with them to West Virginia, they wouldn’t have gotten that money, and since they couldn’t support me they had to work out something. In the state of California a girl can marry at sixteen. So I had the choice: go to a home till I was eighteen or get married. And so I got married.

His name was Dougherty. He was twenty-one at that time and worked in a factory. Then the war came and he was going to be drafted, but he went into the Merchant Marine, and I stayed with him for a while at Catalina, where he was a physical training instructor. Around the end of the war I went to Las Vegas to divorce him. I was twenty. He’s a policeman now.

During the war I worked in a factory. I was in what they called the “dope room”—I had to paint “dope” on the fabric used in making target planes. The work was very boring and life was pretty awful there. The other girls would talk about what they’d done the night before and what they were going to do the next weekend. I worked near where the paint sprayers were—nothing but men. They used to stop their work to write me notes.

The work was so boring I worked very fast just to get it over with. They thought I was doing something wonderful. There was an assembly for the whole plant and the president of the plant called my name and gave me a gold medal and a twenty-five-dollar war bond for “exemplary willingness,” as he put it. The other girls were furious when I got it and they’d bump into me and make me spill my can of dope when I’d go for a refill. Oh my goodness, they made life miserable.

And then one day the Air Force wanted to take pictures of our factory. I’d just come back from my vacation when the office called me in. “Where have you been?” I nearly died and I said, “But I had permission for a vacation!”—which was true. They said, “It’s not that. Do you want to pose for some pictures?”

Well, the photographers came and took the pictures. They wanted to take more, outside the factory, but I didn’t want to get in trouble because I would have missed work—so I said, “You’ll have to get permission.” Which they got, so I worked as a model here and there for several days, holding things in my hand, pushing things around, pulling them . . .

The pictures were developed at Eastman Kodak and the people there asked who the model was and one of the photographers David Conover—came back and said to me, “You should become a model. You’d easily earn five dollars an hour.” Five dollars an hour! I was earning twenty dollars a week for ten hours a day and I had to stand all day on a concrete floor. Reason enough to give it a try.

I started off slowly. The war was over, so I left the factory and went to an agency. They took me on, for ads and calenders—not the one that caused so much trouble; well come to that but others, where I was a brunette, then a redhead, then a blonde. And I really did earn five dollars an hour!

And I was able to pursue one of my dreams. From time to time I took drama lessons, when I had enough money. They were expensive; I paid ten dollars an hour.

I got to know a lot of people, people different from those I’d known, both good and bad. Sometimes when I was waiting for a bus a car would stop and the man at the wheel would roll down the window and say, “What are you doing here? You should be in pictures.” Then he’d ask me to drive home with him. I’d always say, “No, thank you. I’d rather take the bus.” But all the same, the idea of the movies kept going through my mind.

Once, I remember, I did accept an offer from a man I met like that—an offer to audition in a moviestudio. He must have been pretty persuasive. Anyhow, I went. It was on a Saturday and the place was deserted. I should have been suspicious, but I was still awfully naive. Well, the man led me into an office. We were alone. He held up a script and said there was a part in it, but he’d have to see. Then he told me to read the part and to pull up my dress. It was summer and I was wearing a bathing suit under my dress. But when he said, “Higher,” I got scared and turned red and blurted out, “Only if I can keep my hat on!” That was stupid, of course, but I was really scared and desperate. I must have looked ridiculous, standing there holding on to my hat. Finally he got very mad. I was terribly frightened and ran away. I told the agency about this and they called the studio and other places to try to find this guy, but they didn’t. He must have had a friend or somebody who let him use his office.

This incident frightened me so much that for a long time I was determined never to become an actress, after all. It was a difficult time in my life. I was living in rooms here and there—not in hotels, because they cost too much.

And then, as luck would have it, I was on the covers of five magazines in one month, and Fox called me up. And so I was waiting on those hard benches with lots of other people, all ages and sizes and everything. There was a long wait until Ben Lyon, the head of casting, came out of his office. He was hardly out when he pointed at me and said, “Who’s this girl?” I was wearing a white cotton dress that Aunt Anna—I was living with her then for a little while—had washed and ironed for me.

Everything had come up so suddenly that I couldn’t do both—iron the dress and get myself ready- so she said, “I’ll do the dress, you just put on your makeup.” After that long wait, I felt beat, but Lyon was so nice. He said I looked so fresh and young and I don’t know what all. He even said, “I’ve only discovered one other person—and that was Jean Harlow.” Imagine that, my favorite actress!

They made a Technicolor test the next day, which was unusual because they should have had the director’s permission. And then Fox put me under contract—a stock contract for a year.

But nothing came of it, and I never understood why. They hired a lot of girls and some boys, but they dropped them without ever giving them any chances. After they dropped me, I tried to see Mr. Zanuck, but that was impossible. They always told me he was in Sun Valley. I’d come back a week later and they’d say, “He’s in Sun Valley, we’re very sorry, he’s very busy.” After a while you just give up. And then, when I was hired back, after Asphalt Jungle, he said to me, “I understand you used to be here?” I said, “That’s right.” Well, things are a lot different now. And he said I had a three-dimensional quality, reminiscent of Harlow, which was interesting since Ben Lyon had been saying that.

I owe a lot to Ben Lyon. He was the first to believe in me. He even gave me my name. One day we were looking for a stage name for me. I couldn’t very well take my father’s name, but I wanted at least something that was related, so I said, “I want the name ’Monroe,” which was my mother’s maiden name. And so, since he always said I reminded him of Jean Harlow and Marilyn Miller, the great Broadway musical star, he said, “Well, Marilyn goes better with Monroe, so—Marilyn Monroe.” And now I end up being Marilyn Monroe even on my marriage license!

But to get back to where I was . . . I was pretty desperate. Fox dropped me and the same thing happened later at Columbia, even though it was a little different. They at least put me in a movie called Ladies of the Chorus. It was really dreadful. I was supposed to be the daughter of a burlesque dancer some guy from Boston falls in love with. It was a terrible story and terribly badly photographed—everything was awful about it. So they dropped me. But you learn from everything saw no way out. It was the worst time for me. I lived in the Hollywood Studio Club and I couldn’t stand it there. It reminded me of the orphanage.

I was broke and behind in the rent. In the Studio Club they’d let you get about a week behind in the rent and then they’d write you, “You’re the only one who doesn’t support this wonderful institution.” When you lived there, you’d get two meals a day-breakfast and dinner-and you had a roof over your head. Where else could I have gone? I had no family and I was really hungry.

Of course, a lot of people said, “Why don’t you go and get a job in a dimestore?” But I don’t know; once I tried to get a job at Thrifty’s and because I didn’t have a high school education they wouldn’t hire me. And it was different, really— being a model, trying to become an actress, and I should go into a dimestore?

There are a lot of stories told about those calendar pictures. When the story came out, I’d already done Asphalt Jungle and was rehired at Fox with a seven-year contract. I still remember the publicity department calling me on the set and asking, “Did you pose for a calendar?” And I said, “Yes, anything wrong?” Well, they were real anxious and they said, “Don’t say you did, say you didn’t.” I said, “But I did, and I signed the release, so I feel I should say so.” They were very unhappy about that. And then the cameraman who was working on the film then got hold of one of the calendars and asked me if I’d sign it, and so I said yes, I would. I signed it and wrote “To . . .” and then his name, and I said, “This isn’t my best angle, you know.” And of course the studio got even madder.

Anyone who knows me knows that I can’t lie. Sometimes I leave things out or I don’t elaborate, to protect myself or other people who probably don’t even want to be protected but I can never tell a lie.

I was very hungry, four weeks behind in my rent, and needed money desperately. I remembered that I’d done some beer ads for Tom Kelley and his wife, Natalie, and that they had asked me to pose nude. They told me there was nothing to it and that I would earn a lot fifty dollars, the amount I needed. Because they were both very nice to me I called them up and asked Tom, “Are you sure they won’t recognize me?” He said, “I promise.” Then I said, “Well, if it’s at night and you don’t have any helpers . . . you know how to put up the lights . . . I don’t want to expose myself to all the people you have.” He said, “All right, just Natalie and me.” So we did it. I felt shy about it, but they were real delicate, you know, about the whole situation. They just spread out some red velvet and had me lie down on it. And it was all very simple—and drafty!—and I was able to pay the rent and buy myself something to eat.

People are funny. They ask you a question and when you’re honest, they’re shocked. Someone once asked me, “What do you wear in bed? Pajama tops? Bottoms? Or a nightgown?” So I said, “Chanel Number Five.” Because it’s the truth. You know, I don’t want to say “nude,” but . . . it’s the truth.

There came the time when I began to—let’s say, be known, and nobody could imagine what I did when I wasn’t shooting, because they didn’t see me at previews or premieres or parties. It’s simple. I was going to school. I’d never finished high school, so I started going to UCLA at night, because during the day I had small parts in pictures. I took courses in the history of literature and the history of this country, and I started to read a lot, stories by wonderful writers.

It was hard to get to the classes on time because I worked in the studio till six-thirty. And since I had to get up early to be ready for shooting at nine o’clock, I was tired in the evening and sometimes I would fall asleep in the classroom. But I forced myself to sit up and listen. And I was really lucky to sit next to a Negro boy who was absolutely brilliant. He worked for the post office—now he’s head of the Los Angeles Post Office.

The professor, Mrs. Seay, didn’t know who I was and found it odd that the boys from other classes often looked through the window during our class and whispered to one another. One day she asked about me and they said, “She’s a movie actress.” And she said, “Well, I’m very surprised. I thought she was a young girl just out of a convent.” That was one of the nicest compliments I ever got.

But the people I just talked about—you know, they liked to see me as a starlet: sexy, frivolous, and dumb.

I have a reputation of always being late. Well, I don’t think I’m late all the time. People just remember the times I come too late. Besides, I really don’t think I can go as fast as other people. They get in their cars, they run into each other, they never stop. I don’t think mankind was intended to be like machines. Besides, it’s a great waste of time—you get more done doing it more sensibly, more leisurely. If I have to get to the studio to rush through the hairdo and the makeup and the clothes, I’m all worn out by the time I have to do a scene. When we did Let’s Make Love, George Cukor thought it would be better to let me come in an hour late, so I’d be fresher at the end of the day. I think actors in movies work too long hours anyway.

I like to have time for the things I do. I think that we’re rushing too much nowadays. That’s why people are nervous and unhappy—with their lives and with themselves. How can you do anything perfect under such conditions? Perfection takes time.

I’d like very much to be a fine actress, a true actress. And I’d like to be happy, but who’s happy? I think trying to be happy is almost as difficult as trying to be a good actress. You have to work at both of them.

GB: I suppose the portrait of Eleonora Duse on the wall is therefor some reason.

MM: Yes. I feel a lot for her because of her life and also because of her work. How shall I put it? She never settled for less, in either.

Personally, if I can realize certain things in my work, I come the closest to being happy. But it only happens in moments. I’m not just generally happy. If I’m generally anything, I guess I’m generally miserable. I don’t separate my personal life from my professional one. I find that in working, the more personally I work the better I am professionally.

My problem is that I drive myself, but I do want to be wonderful, you know? I know some people may laugh about that, but it’s true.

Once in New York my lawyer was telling me about my tax deductions and stuff and having the patience of an angel with me. I said to him, “I don’t want to know about all this. I only want to be wonderful.” But if you say that sort of thing to a lawyer, he thinks you’re crazy.

There’s a book by Rainer Maria Rilke that’s helped me a lot: Letters to a Young Poet. Without it I’d probably think I was crazy sometimes. I think that when an artist—forgive me, but I do think I’m becoming an artist, even though some people willlaugh; that’s why I apologize—when an artist tries to be true, you sometimes feel you’re on the verge of some kind of craziness. But it isn’t really craziness. You’re just trying to get the truest part of yourself out, and it’s very hard, you know. There are times when you think, “All I have to be is true.” But sometimes it doesn’t come so easily. And sometimes it’s very easy.

I always have this secret feeling that I’m really a fake or something, a phony. Everyone feels that way now and then, I guess. My teacher, Lee Strasberg, at the Actors Studio, often asks me, “Why do you feel that way about yourself? You’re a human being.” I answer, “Yes, I am, but I feel like I have to be more.” “No,” he says, “you have to start with yourself. What are you doing?” I said, “Well, I have to get into the part.” He says, “No, you’re a human being so you start with yourself.” “With me?” I shouted the first time he said that. “Yes, with you!”

I think Lee probably changed my life more than any other human being. That’s why I love to go to the Actors Studio whenever I’m in New York.

My one desire is to do my best, the best that I can from the moment the camera starts until it stops. That moment I want to be perfect, as perfect as I can make it.

When I worked at the factory, I used to go to the movies on Saturday nights. That was the only time I could really enjoy myself, really relax, laugh, be myself. If the movie was bad, what a disappoiment! The whole week I waited to go to the movies and I worked hard for the money it cost. If I thought that the people in the movie didn’t do their best or were sloppy, I was really angry when I left because I didn’t have much money to go on for the next week. So I always feel that I work for those people who work hard, who go to the box office and put down their money and want to be entertained. I always feel I do it for them. I don’t care so much about what the director thinks. I used to try to explain this to Mr. Zanuck. . . .

Love and work are the only things that really happen to us. Everything else doesn’t really matter. I think that one without the other isn’t so good—you need both. In the factory, though I worked so fast because it was boring, I used to take pride in doing my work really perfectly, as perfectly as I could.

And when I dreamed of love, then that was also something that had to be as perfect as possible.

When I married Joe DiMaggio in 1954, he had already retired from baseball, but he was a wonderful athlete and had a very sensitive nature in many respects. His family were immigrants and he’d had a very difficult time when he was young. So he understood something about me, and I understood something about him, and we based our marriage on this. But just “something” isn’t enough. Our marriage wasn’t very happy, and it ended in nine months.

My feelings are as important to me as my work.

Probably that’s why I’m so impetuous and exclusive.

I like people, but when it comes to friends, I only like a few. And when I love, I’m so exclusive that I really have only one idea in my mind.

Above all, I want to be treated as a human being.

When I met Arthur Miller the first time, it was on a set, and I was crying. I was playing in a picture called As Young As You Feel, and he and Elia Kazan came over to me. I was crying because a friend of mine had died. I was introduced to Arthur.

That was in 1951. Everything was pretty bleary for me at that time. Then I didn’t see him for about four years. We would correspond, and he sent me a list of books to read. I used to think that maybe he might see me in a movie—there often used to be two pictures playing at a time, and I thought I might be in the other movie and he’d see me. So I wanted to do my best.

I don’t know how to say it, but I was in love with him from the first moment.

I’ll never forget that one day he said I should act on the stage and how the people standing around laughed. But he said, “No, I’m very serious.” And the way he said that, I could see he was a sensitive human being and treated me as a sensitive person, too. It’s difficult to describe, but it’s the most important thing.

Since we’ve been married we lead—when I’m not in Hollywood—a quiet and happy life in New York, and even more so on the weekends in our country house in Connecticut. My husband likes to start work very early in the morning. Usually he gets up at six o’clock. Then he stops and takes a nap later on in the day. Our apartment isn’t very large, so I had his study soundproofed. He has to have complete quiet when he works.

I get up about eight-thirty or so, and sometimes when I’m waiting for our breakfast to be ready— we have an excellent cook—I take my dog, Hugo, for a walk. But when the cook is out, I get up early and fix Arthur’s breakfast because I think a man should never have to fix his own meals. I’m very old-fashioned that way. I also don’t think a man should carry a woman’s belongings, like her high-heeled shoes or her purse or whatever. I might hide something in his pocket, like a comb, but I don’t think anything should be visible.

After breakfast. I’ll take a bath, to make my days off different from my working days, when I get up at five or six in the morning and take a cold shower to wake me up. In New York I

like to soak in the tub, read the New York Times, and listen to music. Then I’ll get dressed in a skirt and a shirt and flat shoes and apolo coat and go to the Actors Studio on Tuesdays and Fridays at eleven o’clock. On other days I go to Lee Strasberg’s private classes.

Sometimes I come home for lunch, and I’m always free just before and during dinner for my husband. There’s always music during dinner. We both like classical music. Or jazz, if it’s good, but mostly we put it on when we have a party in the evening, and we dance.

Arthur often goes back to work after his nap, and I always find things to do. He has two children from his first marriage, and I try to be a good stepmother. And there’s a lot to do in the apartment. I like to cook—not in the city, where it’s too busy, but in the country. I can make bread and noodles—you know, roll them up and dry them, and prepare a sauce. Those are my specialties. Sometimes I invent recipes. I love lots of seasonings. I love garlic, but sometimes it’s too much for other people.

Now and then the actors from the studio will come over and I’ll give them breakfast or tea, and we’ll study while we eat. So my days are pretty full. But the evenings are always free for my husband.

After dinner we often go to the theater or to a movie, or we have friends in, or we visit friends. Often we just stay home, listen to music, talk, read. Or we go for a walk after dinner in Central Park, sometimes; we love to walk. We don’t have a set way of doing things. There are times when I would like to be more organized than I am, to do certain things at certain times. But my husband says at least it never gets dull. So it’s all right. I’m not bored by things; I’m just bored by people who are bored.

I like people, but sometimes I wonder how sociable I am. I can easily be alone and it doesn’t bother me. I don’t mind it—it’s like a rest, it kind of refreshes my self. I think there are two things about human beings—at least, I think there are about me: they want to be alone and they also want to be together. I have a gay side to me and also a sad side. That’s a real problem. I’m very sensitive to that. That’s why I love my work. When I’m happy with it, I feel more sociable. If not, I like to be alone. And in my private life, it’s the same way.

GB: If I asked you what does it feel like being Marilyn Monroe, at this stage in your life, what would you answer?

MM: Well, how does it feel being yourself?

GB: Sometimes I’m content with myself, at other times I’m dissatisfied.

MM: That’s exactly how I feel. And are you happy?

GB: I think so.

MM: Well, I am too, and since I’m only thirty-four and have a few years to go yet, I hope to have time to become better and happier, professionally and in my personal life. That’s my one ambition. Maybe I’ll need a long time, because I’m slow. I don’t want to say that it’s the best method, but it’s the only one I know and it gives me the feeling that in spite of everything life is not without hope.

Plates

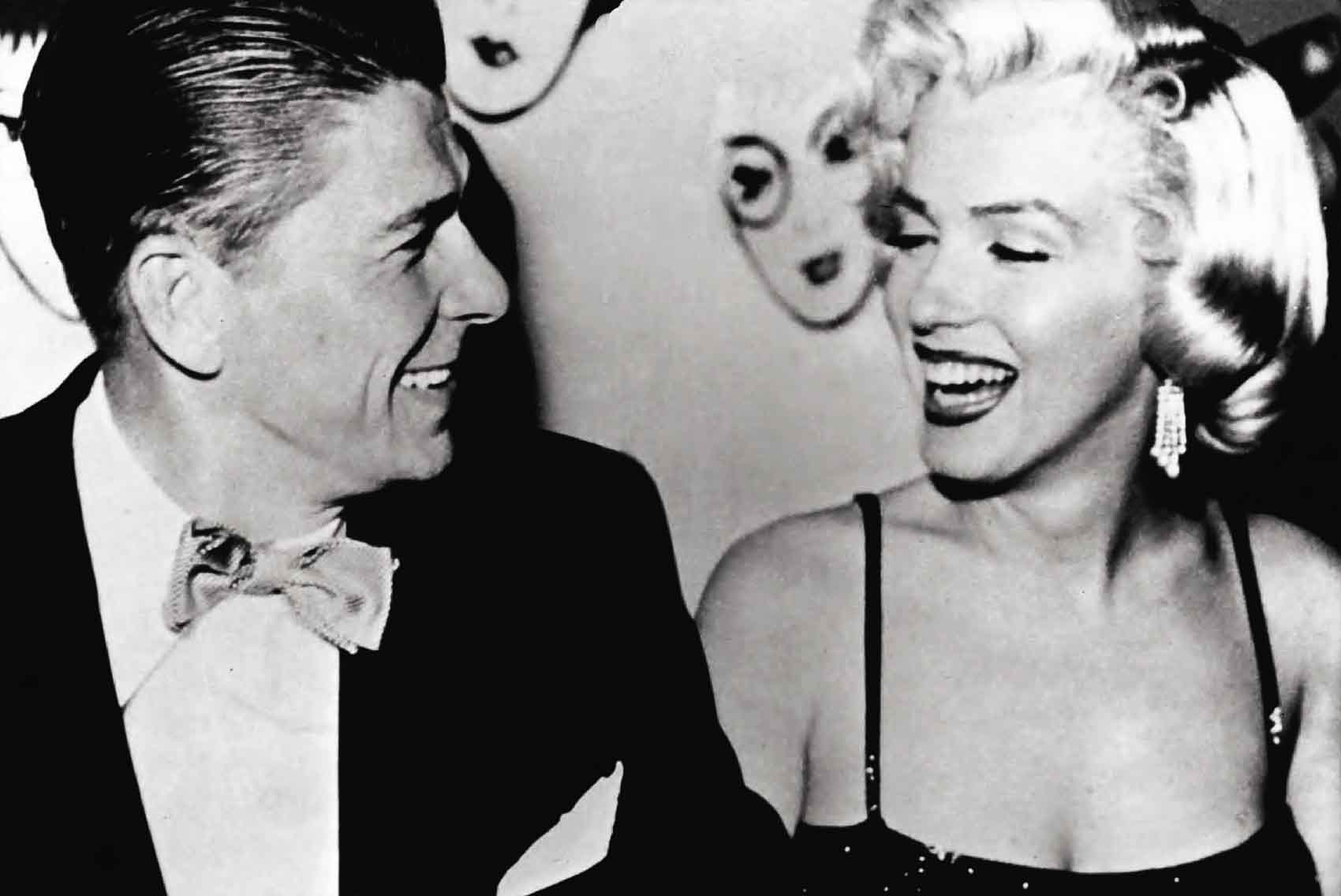

Marilyn Monroe made her media debut as Norma Jeane Mortensen, chosen and discovered by David Conover, photographer for the U. S. Army’s First Film Unit. Conover was assigned by his commanding officer, Ronald Reagan (later president of the United States), to photograph beautiful young women working at jobs vital to the war effort for publicity purposes. On June 26, 1945, in the Radio Plane Corporation, a company owned by Reagan’s friend Reginald Denny that produced radio-controlled target planes, Conover met Norma Jeane, who was working there for twenty dollars a week. He recognized her talent, photographed her, and recommended that she become a professional model. In addition, he introduced her to his photographer friend William Carroll, who took this picture of Norma Jeane in a red sweater and white shorts with suspenders against the background of the blue sky and the Pacific Ocean. Carroll took the photo for an advertising brochure that was meant to demonstrate the quality of a color-processing photo lab.

It is a quote. SCHITMER ART BOOKS