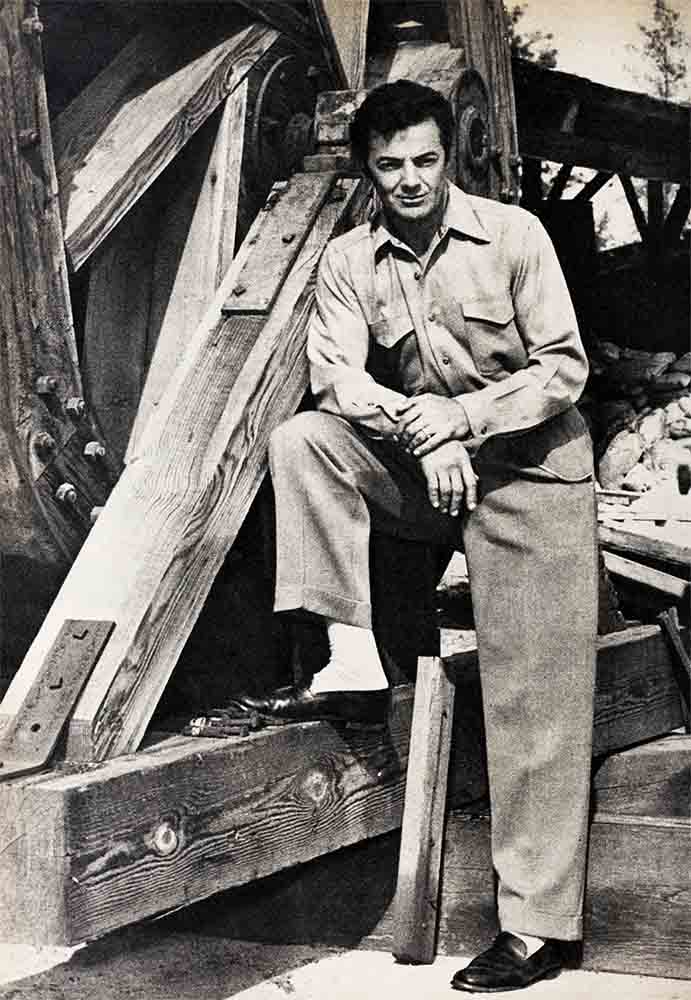

Second Chance For Cornel Wilde

Not too many months ago, a dashing, dark-eyed actor swooped across the nation’s movie screens on his flying trapeze and made a graceful landing right smack in the middle of the hearts of a million palpitating movie fans. As far as the younger moviegoers were concerned, this handsome daredevil was a discovery. Their discovery. And what they wanted to know was why hadn’t somebody told them about this marvelous Cornel Wilde before.

Well, somebody had told them—or at least their older sisters—long before Cornel made his sensational comeback in “The Greatest Show on Earth.” Anyone over twenty can remember that half a dozen years ago, the magazines of America were liberally peppered with his pictures—acting, eating, laughing, loving, sneezing and snoozing. He was a top man on the popularity polls after he played the role of Chopin in the picture, “A Song to Remember’’ nine years ago. And because of the smoldering melancholy Cornel brought to the composer’s life, every album of Chopin’s records was sold right off the shelves of music Stores all through the country, and bop got edged out of first place on the Hit Parade.

Hollywood rushed to offer Cornel Wilde its hottest movie scripts—and for the next few years, the film world was his personal oyster. Then, gradually, the familiar sad old story began to unfold. New faces moved into prominence, new players jockeyed for position, and Cornel began to be overlooked. He had the examples of dozens of other Hollywood careers to go by, and he knew the pattern—the tremendous flush of popularity, the decline, a long slump, perhaps, and then (for the solid performers), the needle pointing little by little upward once more, and the return to a comfortable place in the gallery of filmdom’s dependables. But knowing what to expect didn’t make the reality any easier for Cornel.

That initial dip worries all actors. Why wouldn’t it? Though some are willing to take anything—play any part at all—just keep working, Cornel Wilde is not made that way. He’s an actor’s actor, and behind him are not only years of experience in radio and in stock, but an enviable record on Broadway, including the role of Tybalt in Laurence Olivier’s production of “Romeo and Juliet.”

In 1948, while his career was still skimming the top, he asked to be released from his full contract at Twentieth, and to be given, instead, a contract for just one picture a year. He thought that would give him a chance to pick the cream of the scripts around town. But it just didn’t work out that way.

And, as though having his career go shaky wasn’t enough, his marriage to Patricia Knight began to falter at just about the same time. There was a pathetic irony to the collapse of this marriage. For in Cornel’s earliest days in Hollywood, when the going was really tough, he and Pat were one of the colony’s most devoted couples. But, strangely, after Cornel’s success, things at home never seemed to be the same.

There are some who say that it was ambition—not only Cornel’s tremendous ambition for himself, but for Pat, as well —that shattered the marriage. He insisted on having her in every shot and every interview. To get her into pictures, he wrote her screen test himself—and rehearsed her in it for three days. And when she was cast in a film, Cornel was at her side constantly—coaching her, giving advice to her director, to the camera men. After their breakup, he said, “That was the trouble. I interfered too much.”

They spatted and reconciled and spatted again during those last few shaky months, and through it all, Cornel adored Pat. All he did, he did out of devotion.

When he and Pat finally separated, it seemed that his world was at an end. Cornel considered himself a failure—as an actor, as a husband, and as a father to his daughter Wendy.

Distraught and unhappy, he set off for Europe to make a picture. But the Fate that was pommeling Cornel Wilde still had a blow or two left.

The picture, which was scheduled to be made in London, never even got started. And Cornel spent six frustrating months working on the script—cutting, revising—while the producer and the backers bickered. It was a wasted six months, except for the nostalgic pleasure Cornel found just in being in Europe, where he had spent so much time as a boy. He avoided the brighter spots in Paris, and instead, wandered alone along the banks of the Seine, pondering the weighty questions of both his marriage and his career. There was his daughter Wendy to think about, and there was that huge question mark as to whether he was right in refusing those offers of mediocre pictures.

Discouraged, he went back to New York, where he saw Pat a few times. They agreed then to divorce, and Cornel returned to Hollywood.

The doldrums continued. But even though he wasn’t working in front of the cameras, Cornel wasn’t wasting his time. “I’m not the kind of guy who sits around,” he says. He kept his eyes open for good scripts, and he spent a lot of time writing plays of his own. He went on with his painting (he is a highly skilled amateur—not just a Sunday dabbler) and he kept his fencing sharpened up.

He continued to turn down poor scripts, and he kept reminding himself, over and over again, that he had to learn patience. He tried to pretend that he didn’t mind the fact that the columnists never mentioned his name anymore.

For consolation through it all, he had one thing he knew would never fail him: his talent. He was certain that his day would come again.

It did—with the offer of the role of Sebastian in “The Greatest Show on Earth.” But even that wasn’t all smooth sailing.

Cecil B. DeMille had interviewed Cornel, questioned him and studied him, and—signed a French actor for the part.

Then one day Milton Pickman (now with Jerry Wald productions at Columbia), who had originally suggested Cornel for Sebastian, telephoned him. It seemed the French actor had been devoting so much time to learning the trapeze work that he had neglected his study of English. DeMille wanted to see Cornel again. Mr. Wilde was skeptical.

Here was a movie with Betty Hutton, Jimmy Stewart, Dorothy Lamour, Charlton Heston, and on top of all these star names, a full-blown circus. What could possibly be left in the way of a role for him? But when DeMille told him about the part of Sebastian, Cornel could feel the excitement welling up inside him. It sounded like a great challenge. DeMille said he thought Cornel should play the role straight, rather than as a Frenchman.

“But I can do a French accent,” said Cornel.

DeMille waved aside the suggestion. “I’ve yet to hear an actor do a convincing accent,” he said. “I think it’s better not to try.”

“Would you do me a favor?” said Cornel, “and see a picture called ‘Centennial Summer’? I played a Frenchman in that, and you can judge for yourself.”

The next day DeMille called him up. “Great,” he said. “You’ll play it as a Frenchman.”

Then began the grueling work on the trapeze. Cornel was the last major member of the cast to be signed, and already Betty Hutton had three months of practice behind her. Cornel had only two weeks before the troupe left for Sarasota, Florida, where shooting would begin in the midst of the Ringling Brothers Circus. After four days of it, he was tempted to throw in the towel. Just looking down from the thirty-two-foot platform made Cornel dizzy. The platform itself was rickety, and so small that his heels and toes hung over the edge.

Physically speaking, his most difficult scene was the one where he hung by his knees, caught Betty Hutton in mid-air and then pulled her face up to his for a love scene that lasted three minutes. Professional circus catchers tried it first, and though Betty is no heavy-weight, they could not hold her, with their arms bent, for longer than forty seconds. DeMille decided to throw out the scene, and then Billy Schneider, the trapeze artist who had been coaching Cornel, spoke up.

“I think Cornel can hold her,” he said.

DeMille snorted. “That’s ridiculous,” he said. “If regular catchers can’t do it, how can I expect it of Cornel?”

But Cornel did it—and he did it five times for that many takes. all that morning he had been practicing, holding the one hundred and sixty-five pound Billy Schneider. So that, much as his shoulders and knees ached, Betty’s weight was almost a relief after Billy’s.

By that time, rushes were being seen in Hollywood, and the word was getting around that Cornel’s performance was great. When he got back to the coast to finish filming the picture, he found that cheers and huzzahs were waiting for him.

The career clouds were clearing away. And the same fate that in the black days had made every phase of Cornel’s life completely black, now chose to brighten it at once—on all horizons.

If a script writer were working out the plot, he’d probably be told that he was stretching his story line, that things couldn’t be either all bad or all good. But Jean Wallace came into Cornel’s life— and he knew that things could be all good.

He had seen Jean casually around town for a number of years, but then she had been married to Franchot Tone and he to Pat Knight. And they meant nothing to each other Now, both of their marriages were broken. When he ran into her one night at the Mocambo, he sat down at her table—and they really talked for the first time. The next day, he telephoned her, and in the following months he dated no one else. On September 4, 1951, not long after his divorce from Pat was final, he and Jean were married at the Los Angeles City Hail. Following the ceremony, Cornel rushed to New York for a radio show, then flew directly back for the court hearing in which Jean was asking the custody of her two sons by Franchot Tone.

Cornel’s name was in the news again. And, as an actor he couldn’t help wishing that some of the headlines referred to his skill as a performer. That came not much later—when “The Greatest Show on Earth” began to be seen around the country. The plaudits poured in—and so did the scripts . . . good ones.

Since he climbed up on that shaky platform to play Sebastian, he has made “California Conquest” for Columbia; “Operation Secret” for Warners’; “Treasure of the Golden Condor” for Twentieth, and the soon-to-be-released “Main Street to Broadway” for Lester Cowan.

His greatest ambition—one that he has nurtured for years—is to play the role of Lord Byron in a picture. And it looks now as if he’s probably going to get the chance.

“I’m happier than I’ve ever been in my life,” he says. “I have the really important things the way I like them—my career and my home.”

The home is a Spanish type house in Beverly Hills—a good house for children. When the Wildes moved in, they found the living-room walls covered with picture hooks. Cornel grinned; here was the perfect excuse for hanging his own paintings. And Cornel likes his house best when it’s filled with youngsters. “The more bedlam, the better,” says he.

Jean’s two sons, Jeff and Patty, and her teen-age sister, Karol, live with them. And Wendy joins them on weekends.

As far as Jean is concerned, a career is something she can take or leave alone. She does an occasional acting job on TV, but she’s much more interested in her home and children. Once in a while, Cornel reminds her to call her agent, and, from time to time, he’ll pull her out of the Cub Scout cloud long enough to convince her to read some of the scripts—with possible parts in them for her—that she has a way of leaving about the house, untouched. But he isn’t going to drive her.

If Jean prefers the kitchen to the Klieg lights, that’s good enough for him. He likes just exactly what he’s got these days. And what he’s got is a gal who can ride and hunt and spearfish with the best of them, who can turn out a fine pizza pie, or, if she’s so inclined, a fine performance.

“I know when I’m well off,” says Cornel. “No man ever had a better partner to help him make the most of his second chance.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1953