The Secret Life Of An International Playgirl—Suzy Parker

The nicest thing a man could say about me isn’t that I’m beautiful or he’s wild about me or something like that. The finest compliment he could give me is to say I’m his best friend. . . .”

That was Suzy Parker, talking to a reporter in Hollywood, giving out another of her explosive interviews. That was Suzy Parker, who didn’t give a darn what she said or who heard it.

That was Suzy Parker, who didn’t know that only a few weeks later she would be waiting in anguished uncertainty for a man to say a few short words about her—words on which her reputation, her career, her home, her life would hang.

Not the words she had so casually asked for: “She’s my best friend.” But simpler words by far: “She is my wife.”

And the man wasn’t going to say them.

Until it was almost too late, she was to lie helpless in a Florida hospital bed, both arms broken and useless, mind dazed by the horror of the auto accident in which she was injured and, worse, lost her beloved father—and hear her husband tell the newspapers: “We have been sharing an apartment for years, but we are not married. It is—a very big apartment.”

She was to hear her sister Dorian say indifferently, “I really don’t know if their marriage was ever solemnized—”

She was to see her life crumbing around her—and be helpless to save herself. She was to wait and to pray as she—Suzy Parker who made her own life, thank you—had never done, until finally thank you—had never done, until finally Pierre de la Salle retracted his words, admitted their marriage, and attempted to explain his denial:

“I had been told it was better for Suzy’s career if no one knew she was married. I am a Frenchman; I don’t understand things like this.”

We are Americans. Neither do we.

We don’t understand the sort of world in which a girl, young, beautiful, even brilliant, can prefer to let her friends believe that she is sharing an apartment with a man not her husband—rather than admit the simple truth: that she loves him, is married to him, wants to bear his children.

Yet that world exists and until now, Suzy Parker was part of it.

How Suzy got here

We don’t understand how a girl with so much can. mess up her life so badly. We don’t understand quite where she goes from here.

But we can understand how she got here—by looking back—back to the days before there was scandal and panic and death—the days that led, inevitably, to today.

Back, for example, to the days when George Parker packed up his wife and his four beautiful little girls and moved them, bag and baggage, from their home in New Jersey, to the Florida Everglades—for no apparent reason whatsoever.

Years later, a newspaper telling the story of the Parker girls came up with a reason: George Parker was a Republican, and he moved in protest against Franklin Roosevelt’s third election to the Presidency. Why he should consider a move to be a protest, no one said. Even more, why under the circumstances he should leave Republican New Jersey for Democratic Florida, no one even guessed.

And no one tried. For they were ‘those Parkers,’ and that was all there was to it. George was an inventor; he didn’t go to an office; he didn’t go to the city; he puttered around in a white smock while the neighbors worried over explosions and told their children to stay away from his homemade lab. His family tree dated back to the Mayflower, and so did his wife’s. Children who braved their parents to play in the Parker yard with Suzy or Georgiebelle or Cissy (Florian) or the oldest girl, Dorian, heard wonderful tales about the Parkers’ family, about their Texan grandma who once heard that some people she didn’t like were moving in next door. Grandma didn’t say a word. She just went out on the front porch and sat herself down in her rocker—and rocked—with her shotgun across her knees!! That was all. Sat there all day, rocking and cleaning her shiny black gun—and by nightfall they brought her word that the prospective neighbors had decided to go elsewhere, after all.

That was the kind of people the Parkers were, the children learned. Not afraid of anybody, not afraid of what anybody thought. Oldest family in the country. Proud. Independent.

It all seemed so romantic and brave.

Family life in Florida

Anyway, they moved to the Everglades. They were happy there. Mom joined the Church and the Daughters of the Confederacy and the Daughters of the American Revolution and half a dozen other organizations, and in between meetings she still had plenty of time for her daughters. Dad set up another lab, and in the balmy Florida weather, would disappear into it

for days at a time. Dorian was growing up into the most stunning creature imaginable and talking about getting married, talking about going off to be a model, talking about New York and Paris. Her favorite little sister was Suzy, fifteen years younger than she, and already promising to be just as beautiful. There was an amazing closeness between them that seemed to utterly disregard the tremendous age difference.

And it was Suzy who cried hardest when Dorian finally left home and embarked on the first of her marriages, the beginning of her career. Suzy missed her desperately.

But you couldn’t cry forever, not in Florida where there was so much to do, so many exciting things happening. Like the day Suzy looked up from her dolls to find two big men with fishing poles staring down at her.

“Hey, little girl—this where the Parkers live?”

“Yes.”

“Well, run tell your mother we wanna talk to her.”

Suzy’s chin lifted defiantly. Nobody gave orders to Parkers, not even little ones. “She isn’t home. What do you want?”

One of the men stooped down. “Listen, honey, is your mother the one who’s been actually catchin’ little fish to feed to the big ones in the river?”

Suzy’s chin went up still higher. “Yes, she is, and I help her. I help her catch mosquitoes to feed the frogs, too.”

The men stared at each other, then sighed. “Well, honey, we don’t care if you feed the frogs prime sirloin, see? But tell your mother she’s ruinin’ the fishin’ for miles around here. Them fish won’t even look at our bait, after what your ma’s been servin’ ’em for weeks—”

Those Parkers!

“I like people. . . .”

And there was school. Not that Suzy was so crazy about school, though she liked to read and learn things. But the teachers were always telling you what to do and when to do it, and giving you lists of things you couldn’t do, even when you wanted to—that she hated, that she hadn’t been brought up to expect. But on the other hand, there were the kids—and Suzy loved kids. “I like people even when they don’t like me,” she was to say years later. “Sometimes I like them better when they don’t!” It was true even then. She liked people, and usually they liked her.

Time went by. While other children lived in a round of school, home, parties, Suzy lived half in her own life, half in Dorian’s, related to her by letter. To Suzy they seemed a ticket of admission to a grown-up, glittering world, incredibly gay and exciting.

Someday . . . someday. . . .

And in the meantime, there were Dorian’s visits to look forward to, the days when she would arrive, looking unbelievably sophisticated, wearing stunning clothes, smelling wonderful—to announce that she was getting divorced, or married, or bringing her children—she had three, a boy and two girls—home for a bit while she went to Paris for the winter. Even the divorces and the marriages that didn’t last seemed glamorous when Dorian talked about them. People stayed good friends, it seemed. Life stayed exciting- when you weren’t. tied down. Cissy and Georgie-belle with their high school sweethearts in tow and their dreams of getting married and settling down in a house somewhere—they mightn’t think so. But to Suzy, Dorian’s life was perfection; Dorian was a goddess. She’d like to be like that.

She saved all her problems for Dorian to solve. Like the time she greeted her with a magazine article in her hand.

“Dorian—you know that plastic stuff Daddy’s been working on so long?”

Dorian nodded. “Sure, the stuff he’s been at for years.”

Suzy’s face was troubled. “Well, listen—I read this article and—Dorian—I think somebody made the stuff Daddy’s trying to make, years ago!”

Dorian threw back her head and laughed. “Why, sure, honey. Years ago! But why tell Papa? He’s happy. We have enough to live on—so why hurt him?”

Mama’s method

Mama, perhaps, was closest to reality. At least enough to see through Dorian’s appearance, to reason that any girl who couldn’t make a marriage last couldn’t be as happy as she claimed. She would have done anything for Dorian, if she could—but Dorian wasn’t home. When she was able, though, Mama protected her. There was the time the Hollywood agent, a Roumanian by birth, got hold of Dorian’s photos and phoned her in Florida. Only Dorian wasn’t living home, and Mama answered the phone, listened patiently to the man, inquired about his accent and finally got her chance to speak:

“Oh, you’re a European, you poor man. Well, under the circumstances, you probably won’t understand what I’m going to say. You see, we’re a normal, average, happy, middle-class American family, and I want to keep us that way. My daughter Dorian is impossible already. If she goes to Hollywood, she’ll be intolerable. Please don’t try to find her.” And she hung up.

Perhaps, after all, mama was not so close to reality. Not even the other Parkers would have called themselves average middle class.

Suzy, of course, informed Dorian. “Get in touch with him,” she urged. “It sounds marvelous—you could be a star—”

But Dorian, embarking on her third divorce, wasn’t interested. “Why should I? I’m making lots of money modeling, I’m happy—and I don’t want to be tied down on the Coast. Mom was right about one thing—Europeans are different. I’ve met the most marvelous people in Paris. You’d love them! And they’d love you!”

To Suzy, it was almost an invitation. “Then let me come. Please, Dorian—I’m fifteen, I’m done with high school, I could be a model, too.”

“You could,” Dorian agreed, visualizing Suzy, already stunning, in the right clothes, the right setting. “You could. But didn’t I hear you have a boyfriend in school?”

“Oh, him!” With a wave of her hand, Suzy dismissed him utterly.

“All right,” her sister said. York. Not Paris. Not yet.”

So Suzy said good-bye to her father and mother, good-bye to the boy she’d been going steady with for months, and at sixteen she arrived in New York, to live with Dorian, to be a model. The life of Dorian’s set swept her up instantly. As long as she didn’t act sixteen, no one cared how old or young she was. She learned to, smoke and to order the right drinks; she learned all the latest dances. She learned to be quick with a clever retort and not to notice if the conversation went on, riotously, for hours without anyone saying anything. She learned to flirt with men twenty years older than herself, married men, sophisticated men. It never got past a flirtation, because Dorian wouldn’t let it, because she insisted on taking such care of Suzy that disgruntled admirers protested, “Honestly, you’d think you were her mother instead of her sister!”

The only thing it wasn’t, was a professional success. Why, no one could say, but somehow as a model, Suzy didn’t click. Maybe it was because she was too much Dorian’s type, maybe because even under the layer of quickly applied sophistication, she was still only sixteen, and it showed—whatever the reason, she didn’t make a go of it. When she realized finally that she was going to be living off Dorian for a long, long time, Suzy packed her bags. The Parkers might be dreamers, might be crazy, but they were proud. With resolution and misery, she turned her back on New York and went home.

But once there, she was lost. “Go to college,” her parents urged. “Pick your school, we’ll send you.” Unhappily, she sent away for bulletins, thumbed through them. But she didn’t want to go to college, didn’t want to live in a dorm, keep hours, go to formals, take orders, study nights. What would she talk about with the other freshmen, she who a few months ago had mixed with millionaires, playboys, princes and actresses?

And then, her former steady asked her to marry him.

It was as simple as that. In one hectic hour, her problems could be solved. She would be independent of her parents, wouldn’t have to go to school. She would get her husband to take her back to New York—if she couldn’t live there as a model, she could as a married woman, a gay young married. They would have an apartment, a maid.

It- was ail perfect. She married him without ever remembering that at home marriages were not contracted as easily as they were in Dorian’s set, that they were meant to last forever, that they were supposed to be founded, not on an idea of an exciting life, but on love.

It took only months for her to realize that she would not get the life she wanted out of this marriage, for the boy to realize he had not found a real wife. At an age even younger than Dorian’s at the time of her first divorce, Suzy Parker’s marriage was annulled.

Dorian came to the rescue. “Come back with me. The whole trouble before was that the agency was wrong for you. I’ve found another that really wants young people, new faces. I’ve promised to switch to them, if they’ll take good care of you.”

In a very short time, she was earning even more money than Dorian.

And the next time Dorian went to Paris, Suzy went with her.

It was a strange trip. On board the ship it was just like New York, elegant people, stunning clothes, constant cocktails, much laughter, much money. Suzy was in the center of it all, living it up. But when they got to Paris, Dorian spoke up:

“This is a wicked city. Honestly, Suzy, you have to be really mature to get along in Paris!”

Little sister gets locked up

And Dorian proceeded—incredible as it may seem—to lock her sister in the hotel room every night before she went out.

It was an impossible situation, and it couldn’t last. What was Dorian protecting Suzy from, but the life she herself was leading—the life to which she herself had introduced Suzy? How can you keep an adoring younger sister from following in your footsteps, how can you keep a girl earning almost $100,000 a year locked up at night?

How can you keep her from finding out that you’re in love with a married man?

The answer is simple. You can’t.

The locked doors had to open for Suzy, and they did.

She stepped into a world that made New York look like a hick town.

Here were people who didn’t even bother to get a divorce before they swept off into passionate new loves. Here were men like her sister’s boyfriend, the Marquis de Portago, wealthy, titled, clever—and married—who embarked on new romances knowing there was almost no chance of ending them in marriage—because they could not get a divorce. The Marquis’ mother disapproved of divorce, would have cut off her son’s allowance if he had permanently severed relations with his wife—who was herself a former American model. So the Marquis kept his wife in splendor and his new love in suspense—and it was regarded as perfectly natural. Sometimes he went home to see his children. Sometimes he lived in an apartment in Paris and saw Dorian.

The Marquis introduced Suzy to the fellow who shared his apartment—a freelance writer, named Pierre de la Salle.

Romance in that crowd

This time Dorian was too busy with her own problems to keep a firm eye on Suzy. This time she couldn’t have done anything about it if she had tried.

For Suzy was falling in love.

It came like a revelation; she was utterly unprepared. She saw around her only people whose relationships existed on the surface of their lives, changed, ended, began anew with every impulse.

And she, to her astonishment, was becoming deeply involved, missed Pierre when he wasn’t there with every ounce of herself, wanted him, loved him not for an interlude—but for life.

In Suzy’s world, a pair of happily married people were misfits.

She and Pierre talked it over time and again. It wasn’t that they were afraid of being laughed at. It was that for the first time, they were afraid of losing something precious. Could a marriage survive in their crowd, could a love?

In 1955, she and Pierre were married secretly in New York. Secretly because they were afraid of anyone’s knowing, of anyone’s ripping them apart. Secretly because in their crowd it was much easier to pretend to be merely lovers than husband and wife.

And at this time, Dorian told her that she was going to bear the Marquis’ child, that perhaps when she had done so his mother would be forced to recognize their love, agree to Portago’s divorce and remarriage.

She didn’t mention what the future would be for her innocent child if the plan didn’t work.

Suzy was too much accustomed to the ways of this world to be anything but blasé now. She took the news calmly, went shopping for a baby gift, went on loving Dorian as much as she ever had. But inside, the conviction grew that, much as she enjoyed it, this life was not entirely for her. . . .

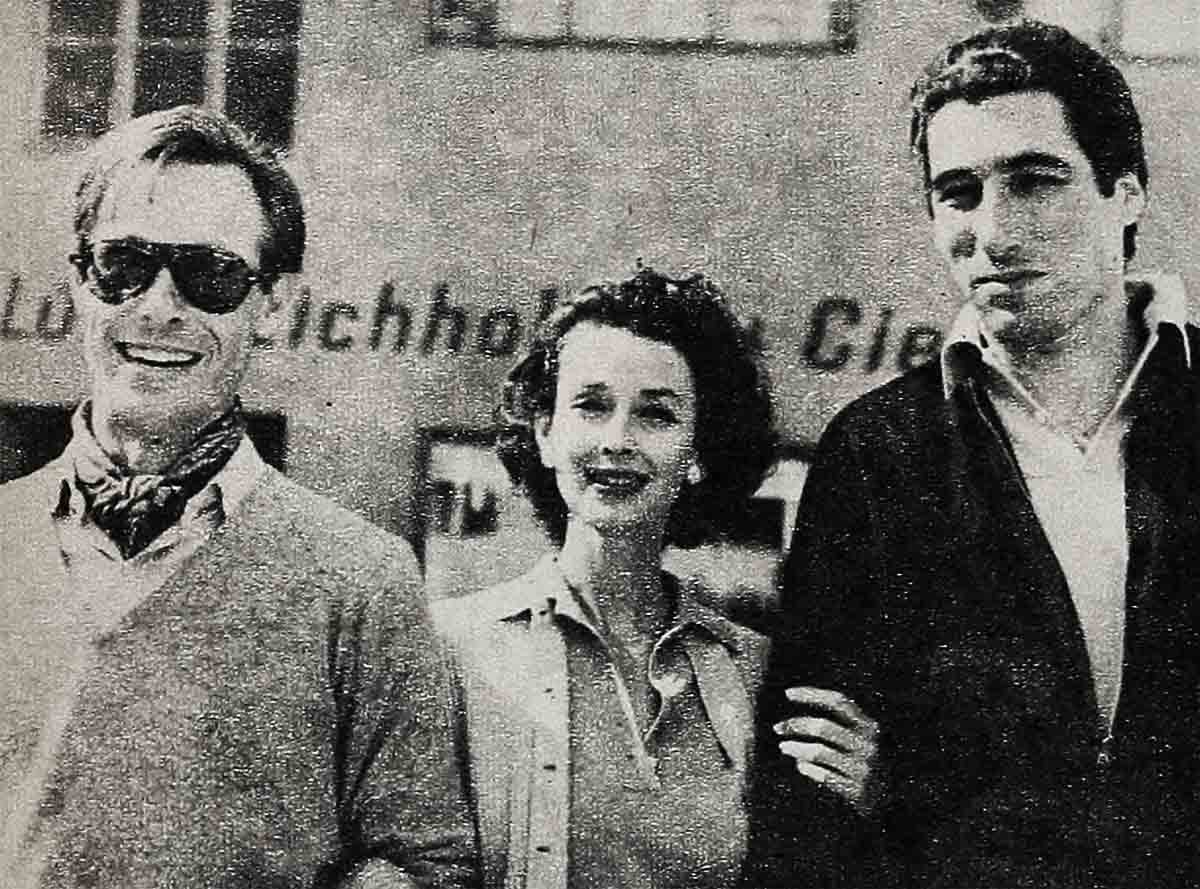

Suzy was in Paris with Pierre when the invitation arrived for her to appear in Kiss Them For Me opposite Cary Grant. She accepted it, knowing she would have to go alone. Pierre, her husband, was one of the crowd of laughing, cheering friends who waved good-bye to her at the Paris airport.

She had taken the offer to make a movie not only because it offered money—she had plenty of that—and fame—that she didn’t need—but because it seemed to extend the promise of a different life. But once in Hollywood she learned that a new star was better off single than married, that her bosses would prefer her that way.

“A little longer,” she wrote to Pierre. “We’ll keep it a secret a little longer. . . .”

Dorian’s child was born, in a hospital in Switzerland. The existence of the baby was a closely guarded secret, until a reporter who had wind of it got to, Suzy in Hollywood. “Is it true?” he demanded.

Without Pierre to help, Suzy had to make up her own mind, and fast. On the one hand there was her mother to be thought of, her mother, who on hearing rumors about Dorian and the Marquis had said proudly:

“We must pray for those who have nothing better to do than spend their I time spreading lies.”

On the other hand there was Dorian, whose baby was supposed to enable her to marry the Marquis. If Suzy denied the baby, might that mean to Portago’s mother that the child was not his?

She came to a conclusion.

“It’s true,” she said finally. And added softly, “But it will be a death blow to my mother.”

Having told that one great secret, she felt free to say anything she liked—and she did. Things like—

I always give different interviews to different people.

I spend money so fast it hurts my conscience.

My mother regards Dorian and me as her punishment for being on earth.

And in Hollywood, New York, Paris, she let people go on thinking that she and Pierre, sharing apartments, going off together on vacations, going home together at night, were not married.

Even Dorian didn’t know for sure.

If it had not been for the tragedy of the car crash, on one of her visits home, killing her father, breaking her arms,—no one might ever have known for sure.

But when they carried Suzy Parker into the hospital, she was not, in that moment, the glamorous model, the new movie star. She was then what she basically had been for a long, long time: a frightened, helpless girl.

And she said then the words she had waited so long to say:

“I’m Mrs. Pierre de la Salle. Somebody tell my husband.”

What Suzy can do

She didn’t know, saying those words, that the worst tragedy was yet to come, that somehow Pierre, flying to be with her, could imagine that the game was still on, the secret still to be kept. She didn’t know that with the story that she wasn’t married spread across every newspaper in the country, her reputation would suddenly seem a precious thing, that she would suddenly need to justify herself and her life in the eyes of a million People—and find that they did matter.

She didn’t know that her scandal would fling its dirt into her father’s funeral, torture her mother in her bereavement, come near to wrecking her own life.

She only knew that the accident somehow brought an end to the old world.

It now remains to be seen what becomes of the new. Whether this marriage-that-wasn’t-a-marriage can be made, after all, into something wholesome and satisfactory, a marriage in which life can be shared, children born, without misunderstanding and fear.

Suzy’s face was unscarred. Her arms will heal. The memory of terror will disappear, as it always does, with time.

But time alone cannot put her marriage back together, cannot give her those first years of love she should have had. Only Suzy can do that for herself.

Only she can make something good and lasting out of the Parker independence, the Parker pride—and her own life. Only she can turn the international playgirl into a real wife. . . .

THE END

—LINDA MATTHEWS

Suzy is now in TEN NORTH FREDERICK 20th-Fox.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1958